Currently, it is estimated there are around 14 million Americans with Right-to-Carry or carrying a concealed weapon (CCW) permits. And the number of peaceable gun carriers is even higher, as there are 10 states where no permit is required for a law-abiding citizen—who is not a prohibited person—to have a firearm discreetly tucked away. And the kind of guns carried by those who exercise their Right-to-Carry are typically small pistols easily concealed on the person. While some carry full-size Government Models and others still prefer short-barreled revolvers, today it is the pocket pistol that is grabbing headlines in gun magazines. And even as the economy ebbs and flows—mostly ebbs—it is the pocket pistol that dealers have a hard time keeping in inventory.

Just to set the record straight, when I say pocket pistol, I am referring to semi-automatics that can be carried handily in the pocket, not necessarily shot while in the pocket. While possible in an emergency, this practice is rough on one’s trousers. Too, if you are carrying a pistol in a pocket, it really should be in a pocket holster. My old boss, American Rifleman Technical Editor Pete Dickey, used to carry an Astra Cub in .25 ACP in his front shirt pocket behind his cigarettes and Zippo, although neither smoking nor Doral carry are highly recommended these days.

When it comes to pocket pistols, you need to determine just what sort of pocket you are talking about. Back when gentlemen wore waistcoats, or vests, the little Browning designs were pocket pistols. Whereas .25s were most commonly called “Vest Pocket” pistols, the subject of this article is how we got to the current crop of .380 ACP pistols suitable for daily discreet carry in the pants pocket—even though pocket 9 mm Luger and even .45 ACP pistols not appreciably bigger than .380s are on the rise.

Pocket pistols can be blowback-operated or recoil-operated, double-action-only, trigger-cocking or even single-action, rendered in polymer, aluminum or steel. They can have mechanical safeties, trigger-blade safeties or nothing but a drop safety. In short, they are diverse yet ubiquitous. And they are made by Beretta, Bersa, Boberg (Bond Arms), Colt, Diamondback, Glock, Kel-Tec, Kimber, North American Arms, Remington, Rohrbaugh (Remington), Ruger, SCCY, Seecamp, SIG Sauer, Smith & Wesson, Springfield, Taurus, Walther and others.

Demand for pocket pistols is not new. But the kinds of pistols being mass produced today, and bearing extremely reasonable price tags, are the result of a progression, with no small influence by legislation over the intervening century or so, and engineering that has resulted in rapid, affordable production. It is estimated that Ruger has made more than 1.5 million Lightweight Compact Pistols at its Prescott, Ariz., facility since 2008. More on the LCP, as well as the LCP II, later.

In previous centuries, gentlemen carried flintlock single-shot pocket pistols, sometimes even with a little folding bayonet on them, in their tailcoat pockets. That gave way to the percussion single-shot that even today still bears a version of Henry Deringer of Philadelphia’s name. William Elliott’s Double Derringer, as made by Remington, was the leading pocket pistol for half a century, and versions of it are still produced, including by Bond Arms in Texas. Too, Remington made a rimfire single-shot actually called “Vest Pocket.” Before there could be semi-automatic pocket pistols, though, there first needed to be smokeless propellant and self-loading firearms.

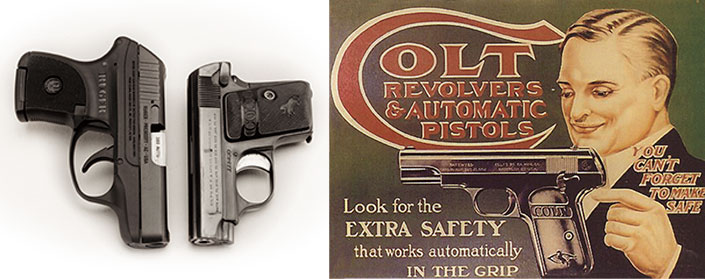

At the turn of the 20th century, the semi-automatic pistol was in its infancy. In its first decade, three cartridges were introduced that would come to define the guns that fired them. Those cartridges are the .25 ACP (6.35x16 mm), the .32 ACP (7.65x17 mm) and the .380 ACP (9x17 mm). All three were developed concurrently with John Moses Browning-designed pistols and made by Belgium’s Fabrique Nationale and Hartford’s Colt. The elegant Colt Model 1903, or Model M, in .32 ACP and then, of course, the Colt Model 1908 in .380 ACP and the .25 ACP Model 1908 or “Vest Pocket” remain the most poignant examples of the American pocket pistol. They were even more widespread throughout Europe. How popular were such guns? Fabrique Nationale presented John Browning with a .25 ACP Model 1905 (its Vest Pocket) marked “Un Million” to commemorate the production of the first million FN Browning pistols in 1914. Mind you, FN’s first Browning-designed pistol, a .32 ACP, was the Model 1899. A million guns in a mere 15 years—and that was only one factory. On top of that, the little Brownings were widely copied the world over, much to the great man’s chagrin.

The semi-rimmed cartridge fed from a detachable magazine allowed for small guns that could carry up to six or eight rounds. The guns of that era reflected the height of style and practicality rendered in steel, with some of them having the nicest Art Deco lines of any guns before or since—others looked as if they came out of a not-well-funded science-fiction magazine.

Contemporary gun literature, and frankly there’s not a whole lot, mentions pocket pistols only sporadically. Mostly, the debate from the birth of the semi-automatic pocket pistol around 1900 to the start of World War II was between short-barreled revolvers or pocket automatics for personal protection. This debate continues to some extent to this very day, though the pocket pistol has far outstripped the snub-nose wheelgun in terms of popularity.

Captain Hugh B.C. Pollard wrote in The Book of the Pistol & Revolver in 1917: “The advantages of the pocket automatic are—rapidity of fire, and the flatness and compactness in the pocket.” It was understood that such guns were commonly used to defend one’s life at close quarters from bandits and blackguards. “The pocket model automatics, .25, .32, and .380 are extensively used for home protection and pocket use,” wrote J.H. FitzGerald in Shooting (1930).

“The average Englishman has little idea how widespread is the habit of carrying a pocket pistol; it is certainly unusual in England but almost customary in the U.S.A. and Continental countries … ,” wrote Capt. Pollard, “After all, it is better to be efficiently armed than not; and ever since the first prehistoric man invented the sling or the bow, weapons that keep the enemy at a distance and disqualified mere personal strength have been popular.” As to carrying a pocket pistol, Capt. Pollard added, “[A] pistol is a wise precaution, as it insures, that, if you are molested, you hold equal or superior cards to your adversaries.”

But just as legislation affects gun design today, too, that turbulent era of the 1910s and 1920s had an influence on guns, especially pocket guns. The Sullivan Act was passed in New York in 1911, essentially to try and keep guns out of the hands of the have-nots, such as the poor or the wrong sort of immigrants. Even at the beginning of handgun permitting laws, they favored the wealthy and politically connected. A century later, some things in the Big Apple haven’t changed.

But there was a far more sinister and racist rationale for some early laws prohibiting concealed carry or requiring a permit, as exposed in Watson v. Stone, a 1941 Florida Supreme Court case in which a concurring justice wrote: “The statute was never intended to be applied to the white population … [T]here has never been, within my knowledge, any effort to enforce the provisions of this statute as to white people, because it has been generally conceded to be in contravention of the Constitution and non-enforceable if contested.”

That era of the 1910s and 1920s saw the introduction of American guns such as the Savage Model 1910, Smith & Wesson .35 cal., the Remington Model 51 (designed by John D. Pedersen), and there was even a version of the Webley autoloader offered by, of all companies, Harrington & Richardson. Continental makers offered little guns such as the Bergmann, Mauser, Walther, Ortgies and Sauer from Germany (quite a few of these designs were striker-fired—Gaston Glock didn’t invent the concept, he just rendered it large and in polymer), the LeFrancais from France, plus other blowback-operated .32s from non-FN factories in Belgium. The rise of Spanish gunmaking was based upon mostly French demand for Eibar- or Ruby-pattern pistols during the Great War, which were plagiarized from Browning. All over Europe, dozens of makers were turning out pocket pistols. There was even a class of fixed-breech four-barrel guns called “Pocket Pistols.”

With the threat of anarchy and Bolshevism in Europe, two things happened after the cataclysm of the Great War; people wanted pocket pistols to defend themselves, while their governments passed laws prohibiting pocket carry—especially among political, ethnic or religious “undesirables.” Gun control laws in Europe eventually stifled much demand for such guns, especially in the 1920s and 1930s. In the United States, most states had existing laws against an average citizen carrying a pocket pistol concealed without a permit.

While the widespread pocketing of pistols may not have been talked about much, there were some classes of people, in particular store owners and shopkeepers, who continued to keep pocket pistols where they belong, in the pocket. Those who carried cash and those who carried badges were the primary consumers interested in pocket handguns. And there were plenty of them considering the size of that market. The true FN Baby Brownings appeared in 1931, and Colt continued to offer the 1903 and the 1908 until 1946. Then other guns began to emerge as Europe recovered from the devastation of World War II. Walthers started to be imported back into the United States, some of them being made by Manhurin in France, there were some small French designs such as the Unique, and then Beretta began importation into the United States. During that period the Spanish makers were emerging as leaders in pocket pistol design and production.

The Gun Control Act (GCA) of 1968 pretty much put an end to European pocket pistol importation through its requirements that a pistol’s combined height and length must not be less than 10" and the gun had to score 45 points under BATF’s “point system” that deliberately penalized pocket pistols. What the GCA’s proponents were after was stopping the import of shoddy, affordable pocket pistols and revolvers, but the venerable Walther PPK—a gun whose quality was never in question—was swept up in the law and prohibited from importation, as was the extremely well-made Belgian Baby Browning. So, after 1968, the newly manufactured pocket pistol became an American-made endeavor. Little Walthers and Berettas would be stamped “Made in the U.S.A.”

Until the 1980s, permits to carry a concealed handgun were discretionary in most states. Meaning they were issued at someone’s discretion—typically a sheriff or police chief. If you were politically connected, carried cash or just happened to live in an area that still respected the right to personal self-defense, gun permits were granted, but people really didn’t talk much about them.

That all changed in 1987. And you can thank one Marion P. Hammer, of the Unified Sportsmen of Florida, and NRA’s first lady president. In 1987 Florida passed the model “shall-issue” concealed carry law in the nation. Although a few other states had already had some form of “shall issue,” it was the Florida law that set the standard for future legislation. Essentially, what it did was recognize for all law-abiding citizens the right of self-defense once again. No longer were citizens completely dependent upon law enforcement largesse, influence or geography for their own personal security. In Florida, if you had committed no crime and were willing to go through the permitting process, you would be able to obtain a CCW permit without having to prove “need” to a bureaucrat. And crime went down.

The effect of the 1987 Florida law would not be immediately responded to by the firearm industry as a whole. But some firms such as Seecamp and Arcadia Machine & Tool (AMT) were ahead of the domestic pocket pistol curve. In 1981, the .25 ACP Seecamp LWS was introduced by a company that previously was in the business of gunsmithing and turning out double-action M1911s. The LWS .25 was a trigger-cocking self-loader, what we now refer to as “double-action-only.” Pull the trigger, and it cocked the hammer and then released it to fire. It was soon followed by the LWS .32 in .32 ACP—and it became known as a gun pocketed by the concealed carry intelligentsia. The Seecamp had neither sights nor an external manual safety, relying on a long, heavy, deliberate pull of the trigger instead. The all-stainless Seecamp finally made it into .380 ACP in 2000, and North American Arms makes a copy of it, too. Thirty-five years later, Seecamp still has a waiting list. Following on the heels of the Seecamp was the AMT Backup series made in .380 ACP, which we first tested in the June 1993 issue, followed by a larger .45 ACP and even a .22 Long Rifle version.

But more pocket pistols were on the way—the two most emblematic were from then-new companies, Kahr Arms and Kel-Tec. In July 1995 there was a cover story written by then Technical Editor Robert W. Hunnicutt titled “Slick Slide Compact 9 mms.” The story on the recoil-operated Kahr Arms K9 and Kel-Tec P-11 began with, “A lot of concealed carriers want the simplicity of a snub-nose revolver with the firepower of an autoloader. Two new trigger-cocking 9 mm compact pistols provide both.” Kahr Arms, under the leadership of Justin Moon, had spent considerable time and money patenting the ideal pocket pistol, first in steel, then aluminum (and later in polymer). Hunnicutt wrote “The Kahr K9 resembles a shrunken Glock enough to cause double takes.”

Kel-Tec’s owner and principal designer, George Kelgren (who previously designed the Grendel P-12 pistol), was onto something, and that something was a single-stack magazine, trigger-cocking operation and a polymer frame. “At a suggested retail price of $300, it should sell in most places at a price not much over a used pistol. It’s definitely worth a look from the budget-conscious defensive user,” wrote Hunnicutt in 1995. Kahr and Kel-Tec were joined by Taurus with the PT-111 Millennium in 9 mm in 1999. As good and affordable as the P-11 was, Kel-Tec’s biggest hit was the 2003 introduction of the .380 ACP P-3AT—the .380s sold like hotcakes.

But even bigger news in the world of polymer-frame, trigger-cocking, single-stack pocket pistols came in 2008. Legend has it that when George Kelgren first got his hands on the Ruger LCP at that year’s SHOT show, he said “Oh well, it was only a matter of time.” In July 2008, Field Editor Wiley Clapp wrote “The LCP is small, light and flat enough to be carried without being noticed at any time and in any kind of attire.” At the time its suggested retail price was $330—and the LCP sells for considerably less today. (Read the review of Ruger's new LCP II here.)

The maturation of the spread of affordable, lawful, personal armed self-defense is expressed in the original Ruger LCP. Sturm, Ruger & Co., which had gone from really the fiefdom of one of the greatest figures in firearm history, William B. Ruger, Sr., had become a publicly held commercial manufacturer with leadership wanting to make the kinds of guns people wanted buy and incredible production capacity to make it happen. What the LCP did was put an old-line name on the pocket pistol once again. Ruger forced an entire industry’s hand. Even Glock, which had clung to double-stack magazines despite consumer demand, joined the pocket pistol pack with its U.S.–made .380 ACP G42 in 2014 and last year with the 9 mm G43. Now it’s hard to find a gunmaker that doesn’t offer a self-loading pocket pistol.

In recent years, the real revolution in pocket pistols hasn’t been in the guns themselves, but rather in how they are engineered for affordable mass production. Too, advances in modern self-defense ammunition have helped legitimize smaller guns. While many self-defense experts regard .380 ACP as marginal for defensive use, there is no doubt that the modern expanding hollow point is far more effective than the ball round of even a few decades ago in stopping a threat. And pocket pistols come in everything from .22 to .45 these days.

Today, millions of law-abiding Americans with pistols in their pockets are heeding the century-old wisdom of Capt. Pollard: “[W]herever the criminal classes use weapons, the respectable classes also adopt them for private defense. The police all the world over share the trait of never being on the scene when wanted.”