Marlin’s modern Model 1895 has been chambered in .45-70 Gov’t since its introduction in 1972. Shown at top is an octagon-barrel model owned by the author’s late friend and firearm industry notable Chub Eastman. Below it is an 1895 Custom Shop gun that has proven to be exceptionally accurate and even more adaptable.

Let’s put the cards on the table: I love lever-actions, but not equally. I’m left-handed. All lever-actions can be operated in ambidextrous fashion, and you’ve got to love that, but the only lever-actions that are truly bilateral in design are top-eject models, which largely leaves out Browning, Savage, the Winchester 88 and all the side-eject Marlins. And while I do have a soft spot for the Marlin lever guns, I didn’t have a great deal of experience with them until recently. Yes, there was a .444 Marlin back in the ’70s, and I had shot some hogs with a friend’s Model 1895 in .45-70 Gov’t in the ’90s. I also did one of the first stories on the awesome .338 Marlin Express, using it for both elk and moose. All worked perfectly, but my experience with Marlin lever guns was far from complete.

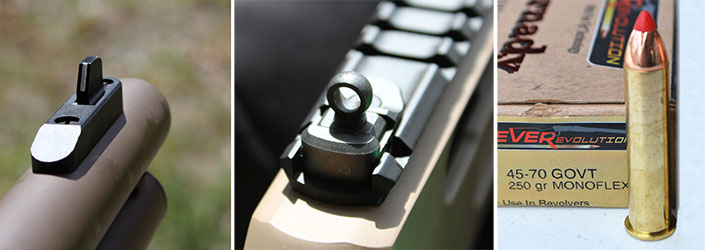

After my buddy and gunwriting colleague Chub Eastman passed, I acquired his Marlin 1895 from his widow, Gloria. It wears standard “buckhorn” irons and seems amazingly accurate, as far as I can see the sights. With some forward weight from that heavy barrel, it is also pleasant to shoot. It’s still on my bucket list to go hunting with it—Chub would like that—but I’m reluctant because I can no longer properly resolve the open sights much beyond 50 yds.—and an optical sight would just look weird on this traditional rifle.

With a long octagonal barrel and shockingly good wood, my Marlin 1895 is a lever-action from another era. Winchester lever-actions get most of the Hollywood glory, but I well recall several appearances of Marlin rifles: Glenn Ford carried one in “Cimarron,” and a Marlin saved Brad Pitt’s bacon in “Legends of the Fall.” Marlin lever guns are cool, and I have long admired the current “guide gun” concept: short barrel, sling swivels, weatherproof finish and some type of updated sighting equipment—maybe a ghost-ring reticle, red-dot sight or low-powered scope.

In factory offerings the “guide gun” chambering is most likely to be the great old .45-70 Gov’t. Up close it hits like a freight train, and the Marlin action is strong enough to use either handloads or “specialty loads” that take the old warhorse up into a different power class.

No matter what loads you use, the .45-70 Gov’t is not a long-range cartridge and, thus, is not versatile. I probably wouldn’t choose it to hunt brown bears. Nobody shoots big bears at long range, but there’s always the chance for a medium-range shot that’s beyond the .45-70’s comfort zone. On the other hand, I’m not a bear guide. Short, handy and powerful, the guide gun really is excellent for close-range defense and for digging a wounded bear out of a thick alder patch. I see it as a great big timber/close cover setup. It will anchor big bucks without excessive meat damage, is equally good for elk and moose in close cover, and is perfect for the biggest black bears over bait or with hounds.

NOT GRANDAD’S MARLIN

Marlin currently offers eight versions of its Model 1895 Big Bore in .45-70 Gov’t: one with a 22" round barrel and half-magazine; a full-magazine rifle with a 26" octagon barrel like my 1895; and six versions with 18.5" barrels. The latter offer good bases for the guide gun concept. From the factory they come in several stock options: straight or pistol grip; wood, laminate or synthetic. The ultimate from the factory is probably the Model 1895SBL: stainless and laminate, six-round-capacity tubular magazine, sling swivel studs, oversized finger loop, and a rail mount with post front and ghost-ring rear aperture. It’s pretty much ready to go (anywhere) right out of the box, but folks, that ain’t all!

The group that owns Remington Arms acquired Marlin some time back—and also Dakota Arms in Sturgis, S.D. It’s known and lamented that there have been delays getting Marlin back up to full production. Not so well known is that the Marlin Custom Shop was moved to Sturgis. There, custom rifles are the order of the day, and the Custom Shop is turning out some of the finest lever-actions I’ve ever seen. The subject of this article is an “ultimate guide gun” from the Marlin Custom Shop, chambered in .45-70 Gov’t and based on a Marlin 1895SBL.

This rifle is not your grandfather’s Marlin. It is a major upgrade, and also extremely modern. If my grandfather had owned a Model 1895 in .45-70 Gov’t, it would likely have been the older “square bolt” model manufactured from 1895 to 1917. The newer Model 1895 is a different design that simply honors the earlier model designation. It traces its roots to 1948 when the Model 36 was updated with a round bolt and became the Model 336. That begat the modern Model 1895 in .45-70, which came on the market in 1972. It was a combination that rekindled a lot of interest in the grand old cartridge—even more so when the short-barreled guide gun version appeared in 1998. Of course the Marlin Custom Shop is fully capable of doing traditional custom work on all manner of Marlin rifles—but its guide gun is a particularly capable lever-action with several practical enhancements.

The laminated stock has been finished with a desert camouflage Cerakote finish; the metalwork has a flat Cerakote finish in desert tan. The rail mount with ghost-ring aperture is maintained, and the bottom of the enlarged finger loop is wrapped with nylon parachute cord matching the stock finish. With an 18.5" barrel the rifle has a 37" overall length, making it quite handy. There’s a lot of steel in those inches; weight is 7 lbs., 12 ozs. In .45-70, I’m not sure you’d want it a lot lighter, especially if you intend to shoot heavy loads. The rifle handles extremely well; I first saw a couple of them at the SHOT Show last year and was intrigued; it seemed a fitting tribute to the guide gun concept—especially if it shot as well as it looked.

FIT AND FINISH

Remington’s product manager for Dakota Arms and the Marlin Custom Shop is an old friend, Carlos Martinez—as is Ward Dobler, a key player at Dakota for many years. I talked to both of them about the custom shop Marlins. Lever-actions are a lot different than the Dakota bolt-actions and single-shots produced in Sturgis for decades. It’s taken a lot of effort, and both Martinez and Dobler are proud of the results. A lot of work goes into these guns, and while the outside is one thing, the inside is another. The Cerakote finishing on both stock and metal are perfect, but this facelift is more than skin deep. The basic Marlin rifle is completely disassembled and the internal parts are polished and smoothed.

And while it’s often said that you can’t do much about the trigger of most lever-action rifles, try the trigger pull on one of these custom shop Marlins and you will instantly feel that this isn’t exactly true. The triggers are crisp and clean, and the example I was sent for this article broke at 3 lbs., 8 ozs. Availability is limited, so it took some time before I was able to get my hands on one. But as soon as I did I took it to the range.

ON TARGET

Marlin’s .45-70 rifles have a slow 1:20" rifling twist intended to stabilize the lighter, shorter bullets most commonly used today. As I said, my 1895 Marlin with 26" barrel is shockingly accurate: At 50 yds. it cuts one ragged hole with every load I’ve tried. My problem is that there’s no point in shooting groups at longer distances because I can’t see the buckhorn sights well enough for it to be meaningful. The rail mount on the Custom Shop guide gun offered a whole world of alternatives.

Naturally, I started with the ghost-ring aperture. Considering the range limitations of the .45-70 Gov’t, I’ve long figured “paper plate” accuracy was plenty good enough. So I started with paper plate drills. Available ammunition was Hornady’s 325-gr. FTX in the LEVERevolution series, a fast load rated at 2050 f.p.s. The ghost-ring aperture at the rear of the rail is both removable (for low scope mounting) and adjustable—but it came out of the box in almost perfect zero at 50 yds.

With aperture sights there’s a compromise to be made. The smaller the aperture, the more precise the sight alignment; the larger the aperture, the faster the target acquisition. The ghost-ring concept is a large aperture, fast but not precise. In my case it doesn’t matter—my days of precise shooting with aperture sights are over! So, although initial accuracy with the ghost ring was surprisingly good, I next went to an Aimpoint Micro red-dot unit that was easily clamped onto the rail mount and zeroed.

Results on paper plate drills at 50 yds. were excellent. At 100 yds. the dot starts to subtend to a size that obscures a bit of the target, but I shot multiple 2" groups. Clearly this dog wanted to hunt. In time I would take the rifle hog hunting, and I intended to use the Aimpoint. Here on California’s Central Coast we’re in the “condor zone,” meaning we have to use lead-free bullets, so I also checked it with Hornady’s 250-gr. Monoflex load, a homogenous alloy bullet. Accuracy was indistinguishable, and out to 100 yds. there was no appreciable difference in point of impact.

This rifle clearly wanted to shoot, so to give it the best chance to strut its stuff from the bench I mounted a much larger scope than I would normally put on a .45-70. Using Leupold’s Tactical mount, I clamped a Minox ZA5 2.5-10X onto the rail. Yeah, okay, that’s not a huge scope—but it still looks silly resting atop such a classic design. However, while magnification has nothing to do with raw accuracy, it sure does make it easier to shoot groups.

The Marlin stock is essentially designed for use with open sights, and it was perfect with the supplied ghost-ring aperture. It was okay with the low-mounted Aimpoint, and I assume it would be fine with a small scope mounted low. With the larger scope the comb was hopelessly low. This also has nothing to do with raw accuracy, but everything to do with getting a comfortable and consistent cheek-weld for shooting groups. I strapped on a left-handed Hornady cheekpiece and adjusted it a bit so the fit was perfect.

With the scope at 10X, shooting Hornady’s 325-gr. FTX load, I would like to say the results were equally perfect, but I don’t know what that means. I do know the .45-70 Gov’t produces a bit of recoil, and firing five five-shot groups “for score” was a challenge. My intention was to cool and clean between groups, which I did, but I noticed significant vertical stringing within the first few groups. This is not uncommon with tubular-magazine lever-actions. The barrel and magazine are pinned together by a fore-end cap. During firing the barrel heats (and expands), but the tubular magazine does not. Too much heat and accuracy can begin to degrade.

Per American Rifleman protocol, I fired five five-shot groups. I took it slow, allowing the barrel to cool between shots in April temperatures that were in the low 70s. Groups were measured at extreme spread with a micrometer, then 0.458" subtracted for bullet diameter. The best group of the five was 0.617", at that large caliber pretty much a ragged hole. The worst was a very mediocre 1.781"—maybe shooter error. But the average for all five groups was 1.321". In bolt-action terms that is not exceptional, but might be acceptable. In a tubular-magazine lever-action firing a 144-year-old cartridge I think it’s impressive. Especially when you consider that there are no “match loads” for the .45-70. Appropriately, today’s factory loads focus on field performance and maximum velocity at pressures low enough to be safe for use in Trapdoor Springfields. Accuracy well under 1 1/2" at 100 yds? I’ll take it. That level of accuracy is all anybody needs from a .45-70—and a whole lot more!

The rifle kicked itself clear of the sandbags with every shot, but .45-70 recoil is more of a push than a hard rap, so it isn’t difficult to deal with. The trigger pull is superb, and loading and unloading were smooth and easy. I noted that there was some velocity loss from the short barrel. Hornady’s 325-gr. FTX is rated at 2050 f.p.s. from a 24" barrel. In the 18.5" barrel, actual velocity was 1745 f.p.s. The 250-gr. Monoflex load is rated a bit slower at 2025 f.p.s., probably from pressure concerns with homogenous-alloy bullets in Trapdoor Springfields and other not-so-strong actions. Actual velocity with the 18.5" barrel was a bit faster at 1805 f.p.s. Obviously the short, handy guide gun concept trades off some velocity, but the bullet is still of large diameter and hits hard. I wouldn’t worry too much about the speed, but you do want to match the bullet to the game you’re hunting.

BRINGING HOME THE BACON

In my case, the light-for-caliber Monoflex bullet was the only available load I could use, so I got a date in April with Chad Wiebe of Oak Stone Outfitters (oakstoneoutfitters.com), about 20 miles north of my house, and checked zero with it and the Aimpoint sight.

Our pigs are down after the long drought, but they’re coming back fast. Against that, we’d gotten good rains, which meant there was lots of food and plenty of water, and the pigs were widely dispersed. In the morning we saw quite a few pigs, but I gave my wife Donna the first shot, and she shot a really big hog with her 7 mm-08 Rem. Now it was my turn, but wind and heat came up quickly and we saw no more pigs.

The evening was cooling fast, good, but the wind was still strong, not so good. Chad and I looked high and low all afternoon, seeing zero pigs, which is pretty unusual in this area. The light was fading, and I was thinking it was going to be another short night and early morning when we came around a corner and saw four pigs rooting at 70 yds. They were all about the same size, maybe 150 lbs., no monsters, but no piglets—all were perfect “eatin’-size” porkers. I picked the one that looked the largest, waited until it turned broadside, and put the red dot on the center of the shoulder.

There was no noticeable reaction, but the other three pigs ran left and that pig ran straight away, lost behind a tree before I could work the lever. I was pretty sure of a hit and so was Chad, but dark was coming fast. Quickly finding blood where the pig had stood, we took the line. The pig was down in less than 40 yds. That little Monoflex bullet had gone in one shoulder and out the other, little damage but a very dead pig—just like it had been hit by a .45-70. Immediately I felt as though I was facing a dilemma: I don’t need another .45-70, and really can’t afford this one. So should I send it back or keep it and take it on a bear hunt?

I suppose I should have anticipated as much after remembering back to the NRA Annual Meetings & Exhibits in Atlanta where several Marlin Custom Shop lever-actions were on display. There were Model 1895s, 1894s and 336s, and when I picked one off the rack and worked the action, I knew that this was not my grandad’s Marlin. Well, it might have been if he’d used it for 40-odd years, because it sure felt a lot slicker than I expected!