Newly-elected Congressman James Madison arrived at New York in March of 1789 with a double burden. In addition to his official responsibilities, he carried a commitment to honor an unusual agreement struck the preceding year with fellow Virginians Patrick Henry and George Mason.

As the largest, most populous state in the new nation, Virginia's ratification of the new Constitution had been crucial to permitting replacement of the flimsy national government under the Articles of Confederation. To secure Virginia's support, Madison, although he was a "Federalist," had agreed to its proposal for amendments to the Constitution that were to become known as the Bill of Rights. Madison's agreement to seek those amendments in the new Congress carried Virginia into the new government.

This support for a Bill of Rights was rather remarkable in light of Madison's earlier conflicts with its proponents. Madison had previously disparaged such amendments as mere "parchment barriers," hardly worth the paper it took to print them. The Philadelphia Convention of 1787, which had drafted the Constitution, considered and rejected a Bill of Rights. This omission provoked anti-Constitution sentiment: two of Madison's fellow Virginians, George Mason and Edmund Randolph, refused to sign the Constitution without such a fundamental guarantee of liberty.

Madison's advocacy of the Constitution also brought him into direct conflict with the immensely popular Patrick Henry. Madison's narrow victory on the Constitution had done little to diminish Henry's populist influence within Virginia. Henry remained unconvinced that Madison's conversion to the cause was genuine.

Patrick Henry's skepticism was understandable. Unlike Henry, Madison had spent most of the Revolution as a member of Congress under the Articles of Confederation. Educated at New Jersey's Princeton rather than William & Mary in his native Virginia, he shared the nationalist sentiments of George Washington and the other Federalists. He had seen the difficulty the United States had in prosecuting a war under a weak central government.

When the Virginia legislature selected U.S. senators, Henry was able to deny Madison the seat he had expected. Instead, two opponents of the Constitution, Richard Henry Lee and William Grayson, were chosen. Madison then sought election to the House of Representatives in a district that was designed to be unfavorable to him. In what was virtually a door-to-door campaign, unheard of in 18th century America, Madison managed to narrowly win a House seat against future President James Monroe.

During the first Congress, several states submitted proposals for a Bill of Rights, and Madison introduced his version in May of 1789. The Bill of Rights attracted remarkably little attention in the Congress. This had not been the case two years earlier, before Madison's commitment to a Bill of Rights. During the drafting and ratification of the Constitution at the Philadelphia Convention of1787, the Federalists argued against the necessity of a Bill of Rights. They had even suggested that a federal Bill of Rights could be dangerous to liberty, for any rights not specifically protected might be presumed to have been forfeited.

By 1789, however, many of Madison's fellow Federalists considered the discussion of a Bill of Rights much ado about nothing. Because it had been a major concern of the Anti-Federalists (those who had opposed the Constitution), it was regarded as little more than throwing a bone to a noisy dog. The Federalists figured that if they could keep the Anti-Federalists busy chasing a Bill of Rights, they would be free to get on about the business of organizing a government without interference.

Madison's difficulty was twofold. First, his fellow Federalists thought the Bill of Rights unnecessary at best and a waste of time at worst. Second, there was no consensus as to exactly which rights should be protected. Further, the Federalists' concern over leaving rights out of the bill presented a legitimate issue.

While there was general agreement over the inclusion of certain rights, there was not necessarily any agreement as to specific language. What would finally become the Second Amendment, the right to keep and bear arms, provides a good example of how the amendment process worked. In Madison's original resolution, the right was guaranteed in the following language:

The right of the people to keep and bear arms shall not be infringed; a well armed, and well regulated militia being the best security of a free country: but no person religiously scrupulous of bearing arms, shall be compelled to render military service in person.

Having used the Virginia Declaration as a model for his resolution, Madison's language varied in two ways. First, he had inserted specific language dealing with the right to bear arms. No such language had been contained in the Virginia Declaration, which spoke in terms of maintaining a militia as the best security for a free people. The proposal that Virginia submitted to Congress did, however, contain the "right to keep and bear arms" language. George Mason, author of the original Virginia Declaration, would have concurred, for he had already stated that the militia consisted of "the whole people."

Second, Madison inserted language which recognized the right to be a conscientious objector. While this provision had been suggested by Virginia and others, it was obvious that he felt strongly that it should be included. This was also in accord with the increasing recognition of religious freedom.

The House Committee made few substantive changes to any of Madison's proposals, though there was considerable change to phrasing. The committee reversed the "militia" and "right to bear arms" clauses in the Second Amendment:

A well regulated militia, composed of the body of the people, being the best security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear aims shall not be infringed, but no person religiously scrupulous shall he compelled to hear arms.

A proposed requirement that the militia be "trained to arms" failed for want of a second.

A major issue with this amendment dealt with conscientious objectors. The full House was concerned that the House Committee version could alleviate a conscientious objector of the responsibility of providing a substitute for military service. Accordingly, the full House changed the language regarding religious objection from not being "compelled to bear arms" to not being "compelled to render military service in person." There was also concern expressed that the national government "can declare who are those religiously scrupulous, and prevent them from bearing arms."

The House version of the Bill of Rights and the Second Amendment underwent considerable change in the Senate. The conscientious objector provision was omitted. The Senate also defeated an effort to insert "for the common defence" next to the words "bear arms." The Senate, for reasons not fully revealed by history, streamlined and reordered much of the language in the Bill of Rights. The Senate version of the Second Amendment is as it was finally adopted by the States:

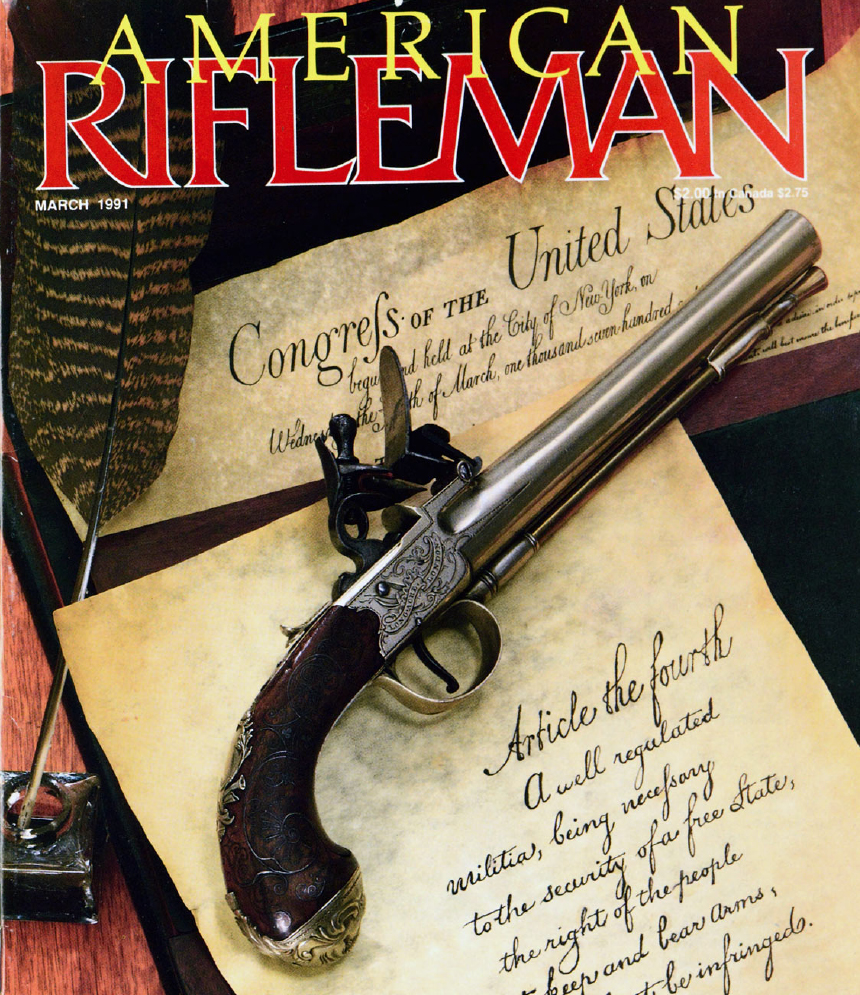

A well regulated militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear arms, shall not be infringed.

Twelve amendments were put forth to the states for consideration. The first two of these, dealing with the population of House districts and compensation of members of Congress, were rejected. Therefore, what appears as the Fourth Amendment proposed by Congress stands as the Second Amendment adopted by the states.

By 1791, the first 10 Amendments to the Constitution, the Bill of Rights, had been adopted. Madison's lonely struggle, against indifferent opposition, yielded one of the greatest documents of liberty ever written. Madison's prediction that the Amendments "will have a salutary tendency" has echoed through the centuries.