This article, "The Mysterious Slam-Fire in the M1 Garand," appeared originally in the October 1983 issue of American Rifleman. To subscribe to the magazine, visit the NRA membership page here and select American Rifleman as your member magazine.

A "slam-fire" is the firing of a cartridge caused by the closing of the bolt as the round is fed into the chamber. Some fully automatic military arms are designed to work on the slam-fire principle, but when slam-fires occur unintentionally, they are disconcerting and potentially dangerous. Recently, a slam-fire nearly deprived me of a good M1 match rifle. Thorough testing to determine what could have caused my slam-fire has restored my confidence. It all started this way:

As I fired a sixth shot in rapid-fire sitting stage, I felt the rifle "double" the seventh round. My immediate reaction was, "I've got an alibi." A split second later, I realized the seriousness of the situation. The stock was completely shattered, the trigger housing blown out, and the right locking lug of the bolt sheared off. Something had struck me high on the forehead, and there was minor bleeding from my left cheek and ear from brass fragments. I was lucky there was no other damage.

Slam-fires are a rare event in the M1 Garand and similar action types such as the M-14, M1A and the Ruger Mini-14. Until this accident occurred, I considered myself a competent and safe reloader. Then I began to question whether I had become careless somewhere in my loading procedures. Since I planned to use this rifle in high-power matches, it was imperative that I determine the cause of the accident.

Soon after my mishap, an article appeared in American Rifleman (February 1981) on a slam-fire in a Beretta BM-62, which is a modified M1. The mishap was attributed to a case separation. When a live round was chambered, it created a force-fit and the next round slam-fired. Could this have been what happened to me?

I began wondering how often slam-fires occur and the possible causes. At subsequent matches I inquired if anyone had any information on slam-fires. When I discovered how little is known about this phenomenon, I tried a series of experiments myself.

Slam-fires do occasionally occur. The cause can usually be traced to one of the following conditions or a combination of them:

Sensitive primer.

The M1-type action has a floating firing pin. As the bolt chambers a new round, the firing pin moves forward and makes a slight dent in the primer. A sensitive primer may fire. A large pistol primer inadvertently used in a reload, or a rifle primer not seated flush, could create the same situation.

Minimum chamber, minimum headspace or inadequate case sizing.

This condition is particularly likely in match rifles with non-military barrels. As the chamber becomes fouled, the cartridges become a wedge fit. The forward motion of the bolt is arrested by the base of the cartridge rather than by the receiver ring and barrel shank. The floating firing pin may then strike the primer with greater force.

Hammer following the bolt.

This happens mostly in match rifles which have had the rear hammer hooks stoned excessively and non-symmetrically in achieving a crisp trigger pull. The sear fails, allowing the hammer to follow the bolt, firing the cartridge before the bolt is properly locked.

Frozen firing pin.

Rust or debris can jam the firing pin in the forward position. This would seem to be an extremely rare occurrence, though I know of one case in which it was probably the cause.

Fouled bolt face.

Debris, such as brass shavings, could act like a fixed firing pin, or could make the case a wedge fit. In cases 2, 3, 4 and 5, the chance of a slam-fire is enhanced if a sensitive primer is present. Also, note that 2 and 3 are specific to match-conditioned service rifles.

When a round slam-fires, the immediate thought is a faulty handload having a high primer. Examination of the recovered base section of my particular case tends to discount this possibility. If the primer had been high and had fired before the round was chambered and the bolt locked, the edges of the primer cup would probably have flowed into the radius of the primer pocket. That was not the case in this particular instance, the primer appearing completely normal.

I returned my M1 rifle to the gunsmith who had converted it to .308 Win. I sent along the ruptured case and recovered parts. Although I fully realize that the accident was not of his doing, I wanted his opinion because I highly value his judgment. During years of work with the Army Marksmanship Unit, he has become quite familiar with slam-fires.

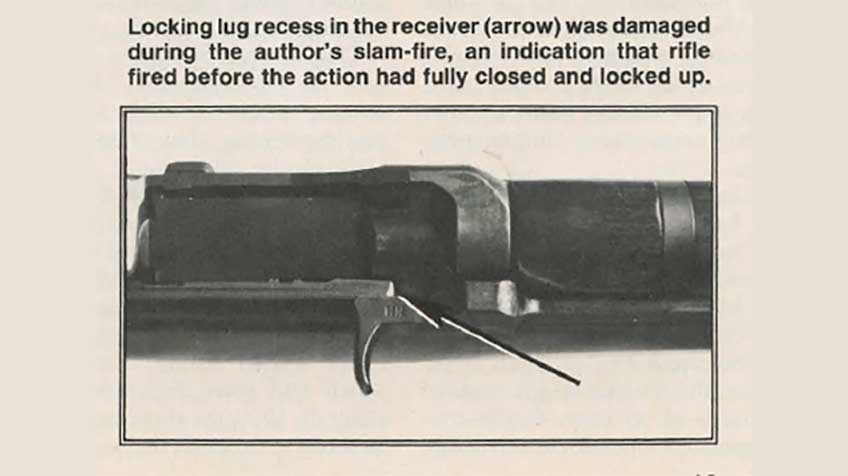

In his estimation, the cartridge had fired as the bolt locked but before the operating rod had traveled fully forward. Under normal conditions, the M1 operating rod has some free rearward travel before it engages the camming surface of the bolt. This free travel ensures that chamber pressure drops to a safe level before the bolt opens.

Since my rifle fired early in the locking phase of the normal cycle of operation, the operating rod did not have any free travel and unlocked the bolt while chamber pressure was still too high. This circumferentially ruptured the case, blew the ejector and extractor from the bolt, sheared the bolt lug and shattered the stock.

Since the barrel and receiver were structurally sound, my rifle was repairable. A new hammer was fitted in case the hammer hooks had failed to engage the disconnector, thus letting the hammer follow the bolt down to fire the cartridge.

When the rifle came back to me, I wanted to shoot it, but I still had reservations because of the slam-fire. I decided to try recreating the circumstances which led to the accident. My main objective was to create a worst-case test and see whether I could induce a slam-fire.

I still had 85 reloads from the lot in which the slam-fire occurred. The following experimental procedure was designed.

Forty cartridges were randomly selected. The bullets were pulled, the powder dumped out and the bullets reseated to the same overall length. Selected powder charges were weighed and found to be normal in all respects.

The cases were checked for adequate sizing. The stripped bolt, disconnected from the operating rod, was used in the rifle as a gauge. The bolt was closed on a chambered case using finger pressure only. The bolt would only close halfway on any case tried. The cases were definitely a wedge fit even in a clean chamber. This identified one factor contributing to my slam-fire.

These rounds were taken to the range for testing. Testing proceeded by loading the test dummy rounds below a normal, full-power round. This ensured that the dummy received full bolt thrust upon chambering. All shooting was done from a bench or from a tight-sling prone position. This helped alleviate cushioning of the rifle bolt.

After firing the full-power round, the chambered dummy was removed and inspected to see if the bullet had been moved forward by a fired primer (remember that primers receive a small firing pin mark upon chambering). A caliper was used to detect any bullet movement. Previous testing had shown that a large rifle primer upon firing can move the bullet forward but that a pistol primer usually will not when the cartridge case is manually placed in the chamber.

The results were interesting. Not one of the cartridges slam-fired. There was no bullet movement. The bullets were pulled and the inside of the cases were inspected for spent primer residue. There was none. All of the test cases had been tumble-cleaned before they were originally loaded. When the powder was removed, all of the cases had clean interiors.

Again, the cases were tested for chamber tightness. The bolt would close on them with only finger pressure, though slight resistance was felt. Obviously, the bolt had chambered these cartridges with such force that the chamber acted like a sizing die.

All the primers showed a firing pin indent. It occurred to me that a firing pin mark might sensitize the primer. If struck again during chambering, it might possibly fire. The bullets were resealed and the entire test was repeated. The results were negative. A few rounds showed bullet movement, but this was believed due to the loss of case-neck tension. Examination showed no primer residue in any of the cases. Where bullet movement occurred, the empty case was fired to ensure that the primer had not ignited.

Still pursuing the possibility of a sensitive primer, another 40 rounds from the previous lot were used. The only difference in test procedure was that rifle primers were removed and replaced with large pistol primers. All cases were de-primed using the same loading dies used originally to load· the cartridges, except that the sizing die was backed off one half a turn so that the cartridge shoulder would not be set back. When these cases were tried in the rifle chamber, they showed the same tightness as the first test lot. The pistol primers were seated below the case head using an RCBS priming tool.

Now two conditions were favoring a slam-fire: a wedge-fit case and definitely a sensitive primer. Test firing was the same as previously described. The results were totally negative. These negative findings led to the following test. Twenty once-fired cases were used because only a few cartridges from the original test group remained.

These cases were sized to give the same wedge-fit as the others. This was done by taking the remaining five untested cartridges, chambering them and measuring the distance from the bottom of the locking lug recess to the bottom of the bolt lug. The new cases were sized until they showed the same bolt-recess clearance.

The cases were primed with pistol primers, but this time all of them were allowed to protrude 0.005" to 0.01" above the case head, with the majority in the 0.007" to 0.008" range. Closer tolerances could not be held because of rim thickness variation, even though a mechanical stop was used on the priming tool. However, the precision was judged adequate for test purposes. Testing was the same as in the previous trials. Now conditions were definitely worse: a wedge fit and a protruding, sensitive primer. Under these circumstances, the pistol primer would be subjected to the full thrust of the bolt.

The tests were negative. Not one primer fired. The bolt seated the primers flush with the case head and sized the cases to chamber dimensions. Afterward, the bolt would close on the cases with finger pressure, and inspection showed no interior primer residue.

It was thought that a slam-fire could be produced if the primer were not allowed to be seated by bolt thrust. Cases with crimped or shallow primer pockets could create this situation. Forty once-fired 1964 M80 Ball cases with crimped primer pockets were sized so the bolt would close on them freely. The primer pockets were lightly chamfered to allow the primer to be seated with force. Twenty cases were primed with rifle primers, the remainder with pistol primers. All primers were slightly protruding. When tried in the rifle, all cases were a wedge fit; the rifle bolt would close only half way with finger pressure. Testing was done as previously described.

No slam-fire was produced, but none of the primers were seated flush by the bolt. The cartridge cases were sized further, allowing the bolt to close on the round. The pistol primers were concave and showed a good firing pin impression. The empty cases were tested in the rifle. Nineteen of the primers fired and there was one dud.

The sound of the fired primers varied. Some had a sharp report, while others produced a flat pop. Examining the cases with rifle primers revealed no significant primer residue, but more than half of the cases had primer mixture scattered over the walls of the case and on the base of the bullet. This suggested that bolt thrust had pulverized the primer pellets without igniting them. The primed cases were tested in the rifle. All misfired.

Measurements of the primer pockets provided an answer. Cases with crimped in primers have deeper primer pockets than uncrimped National Match cases. While the crimped portion of the case head could hold the primer cup, it could not keep the primer anvil in place. The rifle primer anvils were dislodged, allowing the primer pellet to be dispersed.

In the case of the pistol primers, the base of the primer moved inward from the force of the firing pin and bolt, but the anvils were not dislodged. When struck again, the anvil was able to bottom on the primer pocket and complete the ignition. The variation in the report heard was due to the degree of damage to the primer pellet. These results led to the following test.

The object of this experiment was to create a situation where a high primer had adequate anvil support. Twenty cases were sized so that the rifle bolt could be closed by finger pressure. Anvils from fired small pistol primers were flattened with a hammer and inserted into the rifle case primer pockets. This might simulate a condition of repeated reloading without cleaning accumulated residue from primer pockets. The anvils were of the same design as the test pistol primers. Care was taken to ensure that the anvil legs of both primers would coincide.

The primers were seated using a bench-mounted priming tool which permitted good "feel." As a check, several cases were de-primed and the primers inspected. The anvils had set back in the proper manner. All of the test primers protruded approximately 0.007" to 0.008". When the cases were tried in the rifle, the bolt would only half close with finger pressure. Now a condition of a properly sized case with a high, well supported, sensitive primer existed. Testing was done as previously described.

In 10 of the 20 cases, the primers fired. At this point, testing was almost terminated, due to safety considerations. I had fired the fourth round and pulled back the operating rod to eject the test round. It was not there. The test round had slam-fired and driven the bolt back far enough to eject the case, but not enough to lock the bolt. The bullet was jammed into the forcing cone. Several raps from a cleaning rod were necessary to dislodge the bullet. I had visions of a bullet becoming jammed tightly in the barrel, requiring barrel removal to dislodge the bullet. Nevertheless, I resumed and there were no similar occurrences.

I suspect that because this primer was so high, it was fired by the bolt lip dragging across it during chambering. Since the bolt was not even partially locked, the primer was driven out of the primer pocket with sufficient force to partially function the action. The primer blast and bullet inertia was responsible for jamming the bullet in the chamber throat.

This testing was repeated with rifle primers. Only one primer in the test batch fired. It, too, drove the bullet into the forcing cone with enough force that the bullet started to engage the rifling, but did not function the action. This slam-fire was particularly interesting because the primer fired while the bolt was partially locked and the operating rod was not forward.

This condition was characteristic of several rounds in the test, even though they did not slam-fire. With the primer thoroughly supported, the bolt did not have enough force to completely size the case 0.007" to 0.008", so it jammed in the partially locked position. These rounds were so tightly wedged that it was necessary to rap the butt of the rifle on the ground while pulling simultaneously on the operating rod to free the cartridge from the chamber.

Now the testing had come full circle. The next experiment was to create a situation similar to that present when my M1 initially slam-fired. However, an effort was made to produce a cocked primer. If enough handloads are examined, cocked primers are encountered. This is more frequent if priming is done during the resizing operation. Tolerances of the various parts preclude the primer from being seated perfectly true. One edge touches the bottom of the primer pocket while the other is flush with or slightly above the case head.

To create this lopsided condition. The anvil legs were cut from small pistol primers. The partial anvils were placed upon the leg of the test primer and then the primer was seated. This, in most cases, did provide a lopsided condition. No doubt some of the shims moved since they could not be fixed to the test primer. Twenty cases were primed with rifle primers and another 20 with pistol primers. The cases were sized so that the bolt would just close with finger pressure. On casual inspection, these cases looked quite satisfactory. They had to be inspected closely to check for any primer protrusion. With some, the primers were seated flush.

None of the rifle primers slam-fired, but two of the pistol primers did. All of the primers were seated flush by the bolt. Upon inspection, the high side of the primer could be identified because it was marked by the lip of the bolt and I or showed abrasion from the bolt face. Some of the primers had minor depressions from bolt face debris. Testing was terminated at this point.

These tests give some insight into the conditions which might cause a slam-fire, but they should not be considered all inclusive. Several points are evident: (1) a slam-fire is difficult to produce, and (2) it is probable that no single factor is responsible for all slam-fires. (3) The primary factor contributing to a slam-fire is probably the primer. Primers vary in dimensional tolerances, as do primer pockets. They can also vary in sensitivity, particularly if you compare commercial primers to military ones. (4) A worst-case situation could occur where the dimensional variations are incompatible. The most obvious would be a thick primer in conjunction with a shallow primer pocket, resulting in a condition in which the primer could not be seated below the base of the case. If the primer was seated slightly cocked with part of the cup protruding above the case head, and the anvil bottomed firmly in the primer pocket, the potential for a slam-fire exists. For the reloader, such a primer would give the impression that it is seated correctly. If other conditions are present - such as a sensitive primer, tight case, fouled chamber, or debris on the bolt face – the potential risk of a slam-fire is increased. I suspect this was the case when my M1 slam-fired.

Identifying the contributing conditions causing slam-fires has restored my confidence so that I can concentrate on shooting a good match score rather than worrying. If the following precautions are taken, a slam-fire accident should be virtually impossible:

If cases with crimped-in primers are used, remove all the crimp.

Always clean and inspect primer pockets prior to reloading. Accumulated

residue may cause a high primer and I or excessive seating pressure.

Reject any case where difficulty occurs in primer seating.

Make sure that the primers are seated firmly, evenly, and below the base of the case. If necessary, change cases or primers to achieve this condition, and inspect each case after primer seating.

Before reloading ammunition, make sure your resizing die is set so the cases freely enter the rifle chamber. A good check is to remove the bolt from the rifle and remove the ejector, extractor and firing pin. This can be done without stripping the rifle. Replace the stripped bolt, but do not connect it to the operating rod. Place the sized case in the chamber and close the bolt with the fingers. If any resistance is felt, the case should be sized further. When chambering with no resistance is achieved, check the case with a drop gauge, such as made by Wilson, to determine whether the rifle has proper headspace.

With proper chamber dimensions verified, the gauge can then be used to check all reloaded cartridges. No cartridges should be used that gauge longer than the reference case. In minimum-size custom chambers, small base or custom dies may be necessary, but in standard government chambers they are unnecessary and cause reduced case life.

In custom barrels, check the chamber with standard government rounds to see if they are a tight fit. For safety, no shooting should be done with any cartridges that are a tight fit. Tight chambered semi-automatic rifles should be considered unsafe for general use. Reaming the chamber to standard government dimensions should be seriously considered. Of course, with the cartridges being an excessively loose fit, frequent trimming is necessary, and case life will be shortened.

Keep track of how many times a particular lot of cases has been fired. When stretch marks indicating incipient head separations are about 10 occur, smash the cases flat with a hammer and discard that lot of cases. Watch for the bright pressure ring ahead of the case web or check the interior with a thin bent wire for an expansion groove.

Regularly remove and clean the firing pin and its recesses. Keep the bolt face and chamber clean. This avoids any stickiness or tightness, and prevents bolt face debris from acting as a fixed firing pin.

If the trigger is reworked, use prudence in stoning the hammer hooks. Properly done, a safe trigger pull, with an almost imperceptible creep, can be achieved. If you aren't sure of what you are doing, leave trigger work to a qualified gunsmith or armorer.

Use caution in any modification of the ejector, extractor or their springs. Sometimes this is work necessary to achieve proper forward ejection in the M1, especially when converted to the .308 Win. The weakening of the springs or shortening of the ejector lessens their bolt cushioning effect, thereby increasing bolt thrust to the case head.

Shooting glasses must be worn at all times.

The M1 is a good rifle, but it does have its peculiarities. If these are taken into account, a slam-fire becomes an extremely rare occurrence indeed.

Editor's Note:

In recent NRA Technical Staff testing, three slam-fires occurred in the same M1A rifle. (Commercial primers are generally somewhat more sensitive than military primers.)

The slam-fires occurred while chronographing handloads being fired singly, inserting each round directly into the chamber and letting the bolt slam home. When the first slam-fire occurred, it was thought to have possibly been a "high" primer. The safety had been fully engaged and was found to be functioning normally.

Before firing subsequent rounds, each primer was checked for flush seating, yet two more slam-fires occurred in firing a total of about 100 rounds. No case separation or rifle damage occurred, as the rounds chambered fully and the bolt in each instance completely locked.

However, some sized cases from this batch would not chamber freely with finger pressure when checked later.

Fired cases showed significant extrusion of primer cup material into the bolt face, suggesting that the hammer had not followed down, as there wasn't a normal indent. Similar rounds could not be made to slam-fire when inserted into the magazine and fed either singly or in normal semi-automatic firing.

It is suggested that, in addition to the author's precautions, shooters using the M14 or M1A should insert slow-fire rounds into the magazine individually, as this reduces bolt-closing velocity. Don't load cartridges directly into the chamber of M1A or M14 rifles so the bolt and its free-floating firing pin can slam forward unrestrained.—C.E.H.

![Auto[47]](/media/121jogez/auto-47.jpg?anchor=center&mode=crop&width=770&height=430&rnd=134090788010670000&quality=60)

![Auto[47]](/media/121jogez/auto-47.jpg?anchor=center&mode=crop&width=150&height=150&rnd=134090788010670000&quality=60)