While researching Sturm, Ruger & Co.’s 75 momentous years in the firearm trade, I’ve been struck by one common note from numerous gunwriters and editors working during the heyday of company principal William B. Ruger, Sr. The old-timers often spoke of “his” guns, thus personalizing what are normally “their” or “its” references to a company’s collective output. That die was cast when American Rifleman Technical Editor Gen. Julian Hatcher introduced the brand to the world in November 1949, stating, “Some months ago, W.B. Ruger showed us his new pistol … .” Then came: “His deluxe No. 1 single-shot and M77 [bolt-action]” from rifle sage Jack O’Connor; “… his single-action .44 Mag. Blackhawk, of ample size for the powerful cartridge,” judged sixgun legend Elmer Keith; and “… his new double-action .44 Magnum Redhawk,” blared an American Rifleman headline in December 1979—to name a few.

Here were reporters who knew how to convey due credit simply by using the right pronoun.

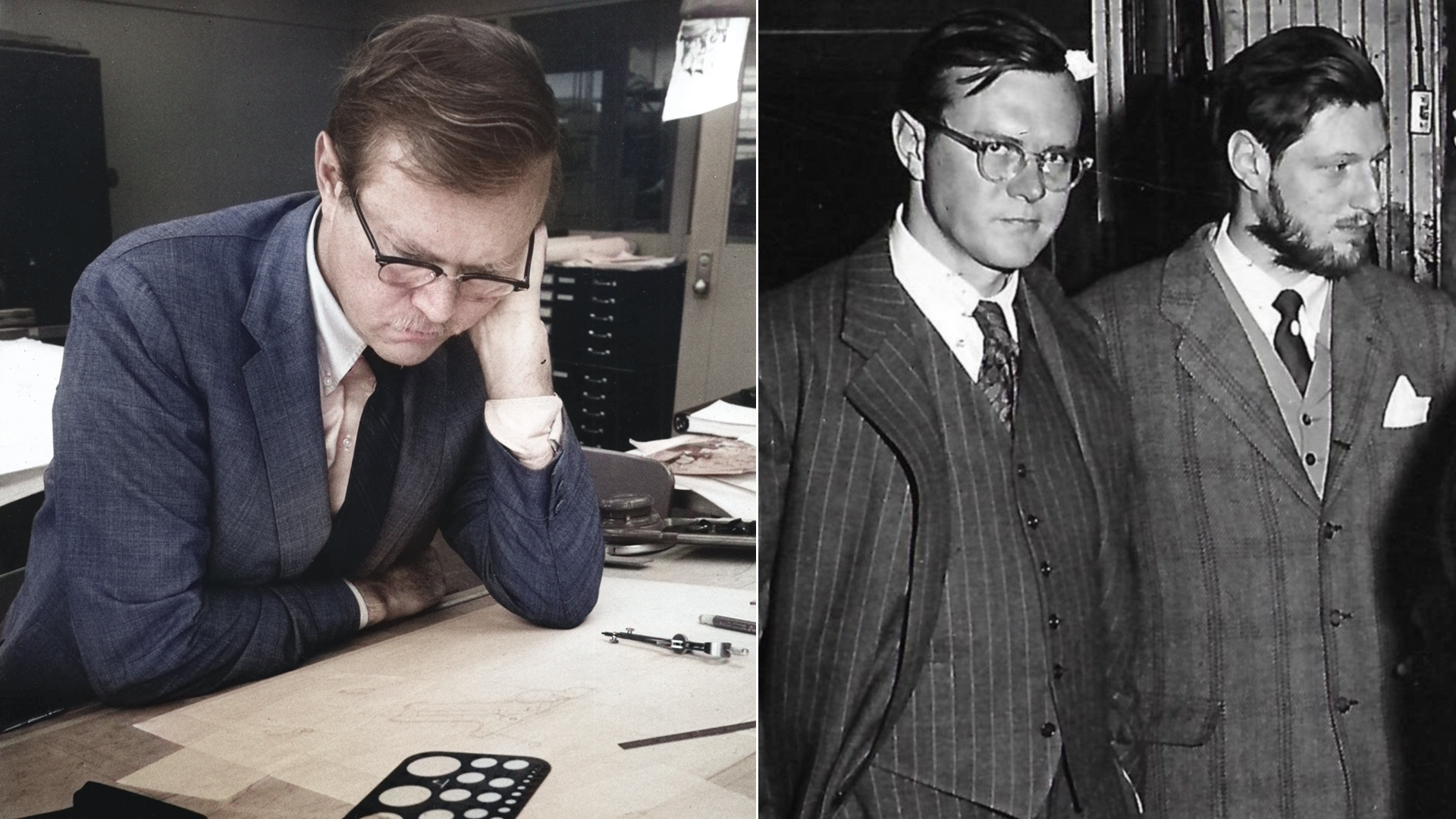

As such, Bill Ruger joined a select group of gun designers whose DNA lives on in the form and function of their inventions. Ruger was a savant whose attraction to guns only started at shooting them. His drive to understand how they worked and were made went beyond taking them apart. In his teens, Ruger was fascinated by the work and tooling he witnessed in a neighborhood machine shop. He fed the fire by poring over a buddy’s monthly copies of The American Rifleman with a zeal that culminated in the December 1943 publication of an article in which he detailed his astonishing conversion of a Savage 99 lever-action rifle to semi-automatic operation.

He parlayed his love of all kinds of guns into a professional versatility that extended from semi-automatic pistols to revolvers to rifles of all major action types to a classy over-under shotgun, from rimfires to big-bores, rivaled only in range by the esteemed John M. Browning. In an epitaph penned for our September 2002 edition, current Editorial Director Mark Keefe named Ruger “… the most significant figure in the firearm field in the second half of the 20th century.” Perhaps an understatement.

Indeed, the company’s first half-century is largely the story of an exceptional man, albeit one who astutely surrounded himself with first-rate engineers, machinists, production managers, salesmen and others in creating an industry juggernaut. By contrast, the following 25 years have been about the transition to a more typical corporate structure. As one of America’s largest gunmakers, it had a clear runway into the 21st century, but nonetheless has depended on a new generation of inspired leadership to maintain its perch atop a market niche that’s always competitive and volatile.

“It is amazing to think that 2024 is our 75th anniversary. I started in this industry in 1989, which, of course, was Ruger’s 40th anniversary! I went to work at Smith & Wesson and spent the first 14 years of my career looking at Ruger as a very tough competitor, but one that I always admired for their super-strong and well-designed firearms and their very diverse line of products. Ruger was still seen as a “newer” brand, with the likes of Marlin, Winchester, Remington and Smith & Wesson being the long-established brands in the market. Now, we have become one of the nation’s leading manufacturers of rugged, reliable firearms. We boast almost 800 variations, across more than 40 product lines.”

“It is amazing to think that 2024 is our 75th anniversary. I started in this industry in 1989, which, of course, was Ruger’s 40th anniversary! I went to work at Smith & Wesson and spent the first 14 years of my career looking at Ruger as a very tough competitor, but one that I always admired for their super-strong and well-designed firearms and their very diverse line of products. Ruger was still seen as a “newer” brand, with the likes of Marlin, Winchester, Remington and Smith & Wesson being the long-established brands in the market. Now, we have become one of the nation’s leading manufacturers of rugged, reliable firearms. We boast almost 800 variations, across more than 40 product lines.”

—Ruger CEO Christopher Killoy, Dec. 8, 2023

Prodigy, Tragedy & Success

The partnership between Alexander Sturm and Bill Ruger was brilliant, even if it ended all too soon. The latter’s boyhood obsession with firearms led to wartime employment with Springfield Armory and Auto-Ordnance, largely in pursuit of an Army contract for a light machine gun conceived when Ruger was in college. Though earning high marks in trials, it was never put into production, and, at war’s end, Ruger left in favor of launching a tool-making concern. The fortunes of Ruger, Inc., were dim, however, and after a few years resulted in insolvency.

Photo by Don Findley.

After war service in the OSS, Sturm worked during the postwar period as an artist and author. From a wealthy family and well-connected—his wife was the granddaughter of Theodore Roosevelt—the young patrician was also an avid firearm collector, which made for a fast friendship when he and Ruger connected in 1948.

Bringing them even closer was Ruger’s design for a .22 Long Rifle-chambered semi-automatic pistol. It rather looked like the German Luger and contained an ingeniously simple blowback operation based on manufacturing efficiencies its inventor learned during his time in government contracting. Ruger was convinced the little gun would challenge pricier category leaders from Colt and High Standard. The one thing lacking was the means to tool up, buy raw materials and hire workers. Sturm supplied necessary capital in the amount of $50,000, and the partners buckled down to finish technical drawings and direct machinists’ work on fixtures and tooling setup. That led to preliminary production of 2,500 sets of components, and finally, product assembly. A small advertisement ran in the August 1949 issue of The American Rifleman, followed by Hatcher’s ground-breaking, favorable review referenced above. A few weeks later, Ruger informed Alex Sturm that his seed money was spent, but then handed over a stack of money orders for $37.50 each, the list price of the Ruger Standard Pistol.

Soon orders were coming in so quickly that the fledgling firm had to discontinue direct-to-consumer sales. In the seminal biography Ruger & His Guns (Simon & Schuster, 1996), author R.L. Wilson records Bill Ruger having remembered “living the good life,” a “happy” time for the partners. The heraldic eagle Sturm created as the company avatar had taken flight. But, in less than two years, with a promising second act in the form of a single-action revolver on the drawing boards, Alex Sturm was stricken with hepatitis and died suddenly on Nov. 16, 1951. Bill Ruger thereafter decreed that in memory of its creator, the flagship pistol’s red-eagle stock medallion should be depicted in black.

Advertisements from American Rifleman archives.

Upwardly Mobile—1949-1974

The success of the Standard Pistol and its Mark I variant gave rise to many new models, a stream that accelerated over time and which aggressively continues today.

In the formative 1950-to-mid-1970s timeframe, definite themes emerged as a result of consumer trends and the owner’s personal interests. “If I personally like it,” he said, “then I can be fairly sure and positive that there will be a lot of other people who feel the same way.” That first decade centered on single-action revolvers, reflecting a surging interest fanned by the advent of television and its devotion to Westerns. First up was 1953’s Single-Six, a rimfire “styled after the famous Peacemaker,” soon followed by the Blackhawk in .357 Mag. and .44 Mag., and then the Bearcat .22 Long Rifle, a throwback to Civil War-era sidearms. While cognizant of the public’s fixation on sixguns, Ruger had also seen opportunity since Colt announced it was ceasing Single Action Army production a few years before. The timing was uncanny.

The focus on wheelguns deviated at decade’s end with an entry into the rifle business. The Model 44 Carbine was a semi-automatic whose “sleek” look resembled the M1 carbine, according to our “Dope Bag” review in late 1959. Groomed to serve as a short-range brush rifle, it arrived as growing deer numbers enticed America’s vets and others to take up hunting. Bill Ruger took the rifle along on his first African safari, and the lengthy list of game collected with it was well-publicized in the sporting press. Adventures over the next few years—including another trip to Africa and a grizzly hunt in the Yukon—stoked the CEO’s lifelong love of hunting rifles, leading to the addictive 10/22 rimfire (1964), handsome single-shot No. 1 (1966) and Mauser-reminiscent bolt-action Model 77 (1968). In totally different ways, all three rifle models became pillars of the American shooting scene and are still treasured by followers.

Growth was so prolific in this formative era that hometown operations in Southport, Conn., soon spilled over into the “Red Barn,” a historic structure that would come to symbolize Ruger’s up-from-its-bootstraps origin. Ruger then built a bigger Southport plant in 1959 and just a few years later branched out to a sprawling industrial campus in Newport, N.H., some 200 miles north of the Connecticut base.

The era’s most significant engineering feat, however, wasn’t a particular design or entry into a new category. Bill Ruger’s obsession with cost containment had led him to an emerging metal-fabrication method called precision investment casting. Essentially, molten metal is molded into near-finished forms, a faster and thus less costly method than forging and machining. For some years, the company strived to educate shooters about how the strength of castings compared favorably with forgings, and, in time, it ceased to be an issue. Ruger parlayed the company’s casting expertise into a subsidiary business—Pine Tree Castings, presently in Newport, and Ruger Precision Metals in Earth City, Mo.—and along with rifle receivers, pistol frames and sundry parts, it supplies aerospace, automotive and other customers.

On point, Bill Ruger was quoted as saying, “It’s not the man who designs or makes the guns that is the true genius. It’s the man who makes the machines which make the guns that is the true hero of this business.”

Demand & Supply—1975-1999

Competing with mega companies that had been in business for a century or thereabouts, Bill Ruger’s startup caught up in about three decades, and according to annual production statistics released by BATFE, has since been America’s largest gunmaker many more times than not. Early on, Remington was the chief rival and on occasion finished on top. In the 2000s, especially during the past decade, Smith & Wesson’s output has surged, but nonetheless Ruger has been the top producer in 11 out of the last 15 years.

Constantly working on new designs, Bill Ruger and his development team vowed to build guns for every interest. In the company’s 1971 annual report, he wrote, “Our product engineering … has proceeded toward long-standing and clearly perceived objectives—significant products in every major segment of the small arms market.” He then echoed that ambition the following year, “… the Company’s long-standing objectives have been to broaden and diversify its line to include firearms of all basic types for both law enforcement and sporting purposes.”

Indeed, law enforcement—whose ranks were growing in response to building unrest and criminality in American society—did merit and receive special attention, which ultimately bloomed into an enduring partnership. Ruger was certain it could build better double-action revolvers than those officers were carrying. Solutions emerged in a trio of related models, the Security-Six, Police Service-Six and Speed-Six, that found willing takers, both among police departments and also in sales to civilian shooters. A new mindset was taking shape, recognition that citizens have the right and responsibility to defend themselves. The mid-1970s also brought the New Model Super Blackhawk and other second-generation single-actions improved by an innovative transfer-bar ignition system.

Long guns weren’t overlooked. Initially a hit among police and foreign military customers, the .223 Rem.-chambered Mini-14 semi-automatic (1975) soon gained a foothold in commercial sales and still remains viable despite going against the AR-15 phenomenon over the past quarter-century. A real ’70s stunner was the graceful Red Label over-under shotgun (1977), whose lines and workmanship rivaled the best Europe had to offer. It debuted as a 20 gauge whose high-tech hammer-forged barrels rode in figured walnut stocks. In due course came a 12 gauge with a showy stainless receiver plus myriad variants, some ornate, some utilitarian. The shotgun closed the loop on Bill Ruger’s long-held dream of offering a “full line.”

These and other newcomers, along with many earlier favorites, made the Reagan years a busy and prosperous time for Ruger. To keep up, the company chose Prescott, Ariz., in 1986 as the site for its second large-scale factory. Production there began with the economical, aluminum-frame P-85, a full-size DA/SA semi-automatic in the resurgent 9 mm Luger. Conceived for civilian, law-enforcement and military sales, the Prescott pistol spawned the long-running Ruger P-series encompassing a dozen succeeding models that persisted well into the 2000s. Compact versions and chamberings such as .40 S&W and .45 ACP became options, along with several stainless-steel models.

Meanwhile, a pair of stainless double-action revolvers were also catering to defensive-minded owners. The larger of the two, weighing 36 ozs. minimum, was the GP100 (1985), with a shrouded 4" or 6" barrel and six-shot .357 Mag. cylinder. A smaller frame made the SP101, introduced in 1989, some 30 percent lighter with barrel lengths about an inch shorter and a five-round cylinder rated for .38 Spl. +P. And impossible to overlook was the new Super Redhawk (1987), a 56-oz., .44 Mag. behemoth. These revolvers and others wore dressy wraparound rubber stocks with wood inserts.

Riflemen also received good news in the form of the revamped Model 77 Mark II (1991). Where the original iteration didn’t fully control feeding, despite its Mauser-like full-length claw, the Mark IIs actually sported an open bolt face and an extractor that engaged the cartridge rim well before chambering. The revised model also featured a receiver-mounted, three-position swing safety. One of the numerous variants was the Mark II Magnum (1992), “a brute” according to Rifleman Field Editor Finn Aagaard, “perfect for the .416 Rigby.” In fact, with that rifle, Ruger was partially responsible for re-birthing what some consider to be the best dangerous-game round ever developed.

Boasting the gun world’s most extensive product lines—and financial statements to match—Ruger was riding high when it was accepted for listing on the New York Stock Exchange in 1990. A press release proclaimed: “Sturm, Ruger has now joined a select group of the nation’s largest, most important corporations.” It wasn’t the first time Ruger stock was made available to the public, but as the NYSE’s first independent firearm maker, it was a mark of respect for the gun industry at large.

Sadly, a dark cloud was looming. The sudden passing of son-in-law Steve Vogel, age 50, in 1991, and younger son J. Thompson Ruger, 48, in 1993, shocked the family, Ruger employees and the communities where they worked. Both men had advanced through the ranks; Vogel to international sales director and Prescott general manager, Tom Ruger as VP of marketing. Though survived by Bill Ruger, Sr., his children, Bill, Jr. and Carolyn Ruger Vogel, and several grandchildren, the family dynasty took a hit from which it never fully recovered.

Re-Armed For The 21st Century—2000-2024

In May 2000, NRA’s National Firearms Museum presented a sweeping exhibit saluting the life and works of William B. Ruger, Sr. Headlining “Ruger and His Guns” were highlights from his personal gun and art collections, including scores of his own designs and the company’s products, along with classics from around the world, plus his biggest invention—a Ruger Sports Tourer automobile.

Bill Ruger had earlier ensured that Americans would have permanent access to these and other treasures by underwriting a museum trust starting with his personal gift of $1 million. That endowment spearheaded the museum’s expansion to three locations across the nation, all of them now meccas of firearm heritage. In the exhibit catalog, biographer R.L. Wilson wrote, “No one in the history of firearms has mastered that world better than he,” but then declaring “Sturm, Ruger is not just ready for the new millennium … [it’s] already there.” In 2001, the NRA Board of Directors paid tribute by electing William B. Ruger an Honorary Life Member, the organization’s highest recognition.

The patriarch soon stepped away from official duties, although he stayed involved in the design of new models until his death on July 6, 2002, but prepared by initiating leadership succession to include non-family members.

“We have been fortunate to have great leadership over the years, innovators who knew the product and cared about our customers. None greater than Bill Ruger, Sr., himself. But that tradition continued through Bill Ruger, Jr., Stephen Sanetti, Michael Fifer, and now I consider myself both fortunate and honored to be in the position to have led this great company these past few years and to help drive us into the future,” observed current CEO Killoy.

Indeed, the legendary founder had designated Sanetti, the company’s longtime general counsel, as president and CEO in 2001. The first of three ex-military men to hold the top job, the former Army JAG officer was succeeded after a five-year tenure by USNA grad Fifer (2006-17) and West Pointer Killoy (2017 to present). Following a legend, no less one as significant as Bill Ruger, Sr., can be perilous, and, in truth, the early transition was an odd rough stretch for the company in terms of revenue and profitability.

Nonetheless, Ruger remained a manufacturing powerhouse and has continued to post profits year over year throughout its seven-and-a-half decades. Along with management succession, Wilson’s bullish outlook also reflected confidence that exciting, newly minted Ruger firearms would keep coming even when the designer-in-chief was gone. After relative quiet during the millennium’s early years, new gun development soon picked up steam in several categories.

Descended from the very first Ruger, the Mark III rimfire pistols (2005) were unveiled in five model variants boasting enhanced handling and ejection. The Model 77 Hawkeye (2007), the third generation of the venerated bolt rifle, won reviewers’ praise for its LC6 proprietary trigger, textbook controlled-round feed and an array of purpose-driven stocks.

CCW folks could have lightweight and compact in both pistol and revolver platforms via the respective LCP (2008) and LCR (2010). In base models, the little semi-automatic was chambered in .380 ACP, had a six-round magazine and weighed less than 10 ozs., whereas the 13.5-oz. DAO wheelgun came with five-shot cylinders in .38 Spl./.357 Mag. Both mini-models have spun off variants that increased cartridge choices along with alternate materials, grips and finishes.

Overseeing the later introductions was Fifer, who came to Ruger with an extensive industrial background, and in very short order introduced so-called “lean manufacturing” processes. Often attributed to Toyota, lean manufacturing relies on decentralized cells where close-proximity work stations simplify the production path from one technician to the next, who perform the sequential steps in fabrication and assembly. The net effect is that parts and the resulting end product move far less and advance more quickly than was the case in previous production lines, an efficiency that slashes per-piece build time and ultimately retail pricing. While inserting lean work lines into busy factories in Newport and Prescott proved to be challenging, the method soon upped production efficiency, and along with surging demand, helped boost net sales by 59 percent over Fifer’s first five years.

Such efficiencies were leveraged to an even greater degree when Ruger established a third major factory, this time moving into a 225,000-sq.-ft. shuttered textile mill in Mayodan, N.C. At an open house for the firearm press in 2014, Fifer explained that the huge, empty space and the location added up to an ideal solution for increasing production capacity. He said the area’s transportation, electrical and water-delivery infrastructure were uniquely scaled to meet Ruger’s needs, and he also expressed confidence in the region’s skilled-labor workforce, notably qualified engineers. Interestingly, Fifer said that expanding existing plants wasn’t considered because he’d learned that after about 1,000 workers, “… you lose touch with employees and bureaucracy starts to build.” Within a few years, Mayodan was in high gear building budget-minded Ruger American bolt-action rifles and pistols, as well as SR556/AR556 modern sporting rifles.

Under Killoy, diverse new models have kept coming at a rapid pace. Notables include: the Pistol Caliber Carbine for home defense, Wrangler .22 LR aluminum-frame revolvers (2019) and Security-380 pistol (2022), as well as cool line extensions like the 10/22 Takedown Backpacker (2020) and M77 Hawkeye Long Range rifles (2018). Development activity has likewise spurred further build-out of Mayodan operations. However, along with business as usual, Killoy has faced two potential turning points.

At the company’s 2018 shareholders’ meeting, an investor group of self-styled “activists” pushed through a motion, in part requiring a report on the company’s efforts in regard to gun safety and producing “safer guns,” plus an assessment of its “reputational and financial risks associated with gun violence.” Included in the group was an order of Roman Catholic nuns, a detail amplified via resulting anti-gun media clickbait. While the group’s objectives were vague, it was perfectly clear that this was an attempt to embarrass the company and the firearm industry, and Killoy refused to take the bait. “The proposal requires Ruger to prepare a report. That’s it. What the proposal does not, and cannot do, is to force us to change our business, which is lawful and constitutionally protected,” he retorted. “What it does not do, and cannot do, is force us to adopt misguided principles created by groups who do not own guns, know nothing about our business and frankly would rather see us out of business.” With that stance effectively defusing the dissident action, the Ruger boss didn’t just shield his company and its workers—his refusal to be bullied was a blow for freedom for all gun owners. Similar measures have been floated since but were tabled or voted down.

Another decision will have a more lasting impact, and it’s one that excited vintage rifle fans; it was also unprecedented. While all other major U.S. gun manufacturers have sought growth through in-market mergers/acquisitions and/or by co-marketing with foreign makers, Ruger’s brand fidelity and made-in-America pride was unyielding. However, that partly changed when Killoy called in the winning bid for Marlin during the bankruptcy auction of Remington Outdoor Corp. properties in September 2020. For $28.3 million, Ruger acquired the trademarks, intellectual property, machinery and other assets, and within a year, Mayodan was producing a mechanically improved Model 1895 SBL. Recently added Model 1894s and 336s have throwback looks, but also function better than ever. Convinced that the move would boost sales, create jobs and bolster share value, Killoy said, “It’s a great fit for both companies and customer bases—two American firearms brands known for delivering great value. We’ve heard from countless [gun folks]—retailers, distributors, writers and collectors—who are delighted.”

At Ruger’s various plants today, every gun is still built by U.S. workers and contains mostly U.S.-made parts. Taking stock in this anniversary year, it’s obvious that the company’s identity is backlit by the historic vigor of its founder and the enterprise he built. Equally clear is that ongoing energy and achievements confirm our trust in Ruger.

“Although 75 years is a tremendous milestone, it is still only the start for us,” Killoy promises. “We don’t plan to slow down, and we work hard every day to continue to build on the innovation that we have become known for! As good as our products are—it is our people that really set us apart. I am so proud of this team and how hard they work every day to bring great firearms to our customers. This year, we will once again launch many new and exciting products, and we plan to continue to be a leader in the industry for the next 75 years!”

The Responsible Gun Maker

Since the beginning, Bill Ruger, his guns and the company’s business practices earned all sorts of superlatives, and for good reason—he was especially driven by a sense of responsibility and as much as anything wanted that to be the company’s public face. As early as the 1950s, Ruger messaging in many forms harped on this through the motto, “Arms Makers For Responsible Citizens,” and the credo, “With the right and enjoyment of owning a firearm goes the constant responsibility of handling it safely and using it wisely.” Clearly, Ruger wasn’t content merely to conduct business without setting a high standard, both for the company and its customers. While ethics rarely play into sales pitches, Ruger’s obviously struck a chord with the target demographic—responsible gun owners.

Corporate responsibility was much more than just a talking point at Ruger. The man and the company obsessed over the affordability of its guns. As its offerings increased and diversified, Ruger products have almost never been the most expensive in their respective categories. Across the decades, media coverage has routinely praised the value delivered by whatever Ruger is being considered, a principle extending from entry-level rimfires to exquisite safari rifles. Here’s the gist, as parsed by gifted gunwriter Terry Wieland in his book Dangerous Game Rifles (Countrysport Press, 2006): “Ruger was a gun lover, pure and simple. He liked finely made firearms and also firearms that were purely functional and delivered the goods without fanfare … . He had an instinct for what shooters liked, wanted and were willing to pay.” As such, nearly every part in every Ruger design has received meticulous scrutiny for performance and cost effectiveness.

Ruger philanthropy is likewise a measure of the responsibility ethic. Either personally or as a corporate donor, gifts to youth programs, firearm museums, public-land acquisition and local charities have echoed the values that matter to gun owners. Notably evident is the company’s devotion to firearm freedoms, support not only realized through generous monetary donations to NRA and others, but also in public advocacy. Bill Ruger testified before Congress three times, always from a position of pride, strength and speaking truth about a right he felt was not open to debate. Said Ruger before the House Judiciary Committee in 1978, “As a citizen and a businessman who has had extensive experience with bureaucracies at every level of government, I have learned that if you fear to speak out when you should, then you may soon find that you won’t even have the right to speak out.”