This article, "Col. Jeff Cooper," appeared originally in the October 1993 issue of American Rifleman. To subscribe to the magazine, visit the NRA membership page here and select American Rifleman as your member magazine.

Some years ago, Big Bear Lake, a southern California ski resort town, put on a 'Miners' Days" extravaganza for the commendable purpose of attracting its share of summer tourists. Among the major activities was a "Leatherslap" fast-draw contest, organized by a retired colonel of Marines, John Dean Cooper, always known as 'Jeff.'"

Decrying the blanks commonly used in "fast-draw" matches—Cooper held even then that the purpose in shooting is to hit the target—he decided on man-on-man bouts using paper silhouette targets at about 7 yds.

Though paper targets made it difficult to determine the match winner, the Leatherslap was a huge success, so much so that it became first an annual and then a monthly event, and the Bear Valley Gunslingers and later the South West Combat Pistol League were formed to run it.

In that first Leatherslap, single-action "cowboy" and double-action police revolvers predominated. Only Cooper and Hugh Carpenter were eccentric enough to use the 1911 Colt .45 pistol. All held their guns with one hand, naturally, and most employed point or hip-shooting, though Cooper says he did use the sights. The next year, a deputy sheriff named Jack Weaver shocked everyone by winning decisively while holding his revolver in both hands, and handgunning was changed forever.

Weaver was far from being the first pistolero to use both hands. Although the pistol was developed mostly as a cavalry arm that was necessarily used one-handed in order to leave the other free to control the steed, it had on occasion been grasped in both hands, probably from the beginning.

For example, in his 1930 book, Shooting, J.H. FitzGerald has a photo of himself using a two-handed hold that, at least superficially, resembles the Weaver stance. "Very accurate shooting can be done ... and the officer will find he can shoot faster and with more accuracy after a run if the arm is held in this manner," he advises.

There is an illustration of a young Elmer Keith using two hands in his book Sixguns, and Don Martin, writing in the 1957 Gun Digest, advocated a two-handed hold in the field. None of these men suggested that the two-handed grip originated with him.

However, there is more to the Weaver than holding the pistol in both hands. Normally the weak-side foot is slightly advanced so that the supporting arm elbow can be bent while the firing arm is fully extended, or nearly so. The supporting hand pulls back against the firing hand to set up isometric tension that controls muzzle flip and tends to return the pistol to the original line of sight after each shot.

This principle is what distinguishes the Weaver from all other stances, and if the earlier exponents of two-handed pistol shooting knew about it, they made no mention of it that I can find.

Jeff Cooper was born in 1920 into a comfortably well-off California family that kept a summer home on Catalina Island, where he ran free during his formative years. He was introduced to rifle shooting at age 11 (a rather ripe old age, he says), acquired his first rifle, a Remington Model 34 .22 rimfire that he still owns, at 14, and was harassing the wild goats with a .22 Hornet ("not enough gun") at age 16.

Thus he began his shooting career with the rifle, though he did gain some experience with the handguns used to kill sharks on a fishing boat owned by one of his father's friends, including a broomhandle Mauser.

Cooper joined the Reserve Officers Training Corps in high school because it issued free .22 ammo to the rifle team, and continued in it at Stanford University, where he earned a BA in political science and met the girl who would become his wife.

In those days, the Marines were permitted to recruit from the Army ROTC. The enticement they offered, besides the glamour of an elite unit, was a regular commission as opposed to a reserve commission in the Army.

Cooper was commissioned a second lieutenant in the Marine Corps in September 1941 and was attending Basic School when Pearl Harbor was attacked. He served the first 2.5 years of the war in the Pacific on the shore bombardment battleship Pennsylvania,and was preparing to invade Japan with the 3rd Marines when the atomic bombs were dropped.

He spent a few years after the war as a student and staff instructor at the Marine Corps Command and Staff School at Quantico, Va. There he began his serious research into the art of the combat pistol by evaluating an FBI course, after which he and Capt. (later Col.) H.G. Taft created a radical “Advanced Military Combat Pistol Course." Some elements of that course are still in use today.

After a brief spell as a civilian, Cooper served through the Korean War in clandestine operations so covert that his oath of secrecy still prohibits him from discussing them. He resigned with the rank of lieutenant colonel in 1955 and settled with his wife Janelle and three daughters into a large house in Big Bear Lake. He dabbled in automobile racing, and wrote some articles about it for one of the Petersen's magazines, but did not find his true vocation until that first Leatherslap.

Cooper realized that competition was the means by which the full potential of the combat pistol could be discovered and the tool by which the best techniques for realizing that potential could be developed. To that end, he insisted on freestyle competition.

"Service-type" sidearms and ammo were to be used, and all strings started with the pistol holstered, but apart from that there were few limitations, and competitors could use any technique, stance or holster they chose.

Targets included balloons, paper silhouettes and-metal gongs, at ranges from arm's length to more than 100 yds. The courses of fire were diversified so that none was repeated during the competition year, and all attempted to simulate real-life situations that might occur on the street.

From all this, men like Jack Weaver, Elden Carl, Ray Chapman, John Plahn, Thell Reed and Cooper developed the "Modern Technique" and learned to shoot the pistol so well that it was elevated, as Cooper remarked, from being a mere badge of office or last-ditch trinket to a serious personal-defense tool. In this open competition, the Browning-designed M1911 Government pistol proved to be the best handgun available.

The Weaver Stance is only one component of the Modern Technique, which includes among other things the use of the flash sight picture even at close range, the compressed surprise trigger break, proper gun handling, safety rules, malfunction drills and reloading, and perhaps above all, the combat mindset.

Cooper has written that "Man fights with his mind. His hands and his weapons are simply extensions of his will…” He says that of the 50 or so of his students who have been involved in lethal confrontations, not one student claimed to have saved his life by his dexterity or his marksmanship, but rather by his mindset.

He defines the combat mindset as “…that state of mind which ensures victory in a gunfight. It is composed of awareness, anticipation, concentration and coolness. Above all, its essence is self-control. Dexterity and marksmanship are prerequisite to confidence, and confidence is prerequisite to self-control.”

Cooper wrote about this new doctrine of practical pistolcraft, and presently he was being asked to teach it, mostly overseas. Working with the “good guys” in hot spots in Latin America, Europe and Africa, he evolved simple and effective ways of teaching the modern technique.

The demand for his services grew so that he was seldom home, though he did find time to earn his masters in history at the University of California, Riverside, in 1965. Finally, in 1975, he and Janelle moved to Gunsite, a 200-acre ranch near Prescott, Arizona, where he created the American Pistol Institute, now Gunsite Academy, a complete school for small arms. The first class gathered in the fall of ‘76.

In the meanwhile, the popularity of practical pistol competition had grown so enormously both at home and over-seas that a conference was held the same year at Columbia, Missouri, which resulted in the formation of the International Practical Shooting Confederation (IPSC), with Cooper as founding president, and with DVC—Diligentia, Vis, Celeritas (accuracy, power, speed)—as its motto.

Cooper has always regarded competition primarily as a research tool, and as a means of improving one's ability to defend himself and others in an increasingly dangerous world. Of late, however, the “gamesmen” have rather taken over IPSC (as inevitably happens),) with the result that its courses of fire, and the equipment and techniques used, are becoming somewhat detached from real-world defensive pistolcraft, It remains great fun, though.

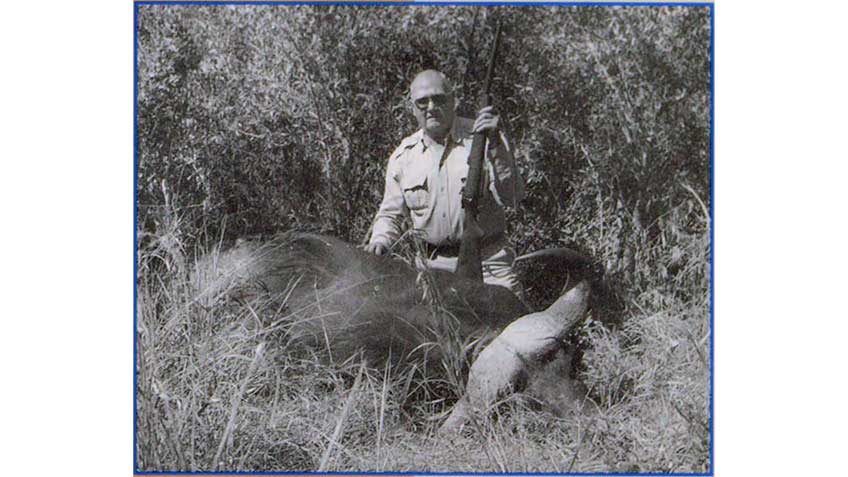

Cooper is a serious student of the rifle, and a big game hunter of considerable experience both in this country and in Africa. He has developed two designs that he feels will cover most of the practical applications to which the rifle may be put in the field. The first is the "scout rifle," a light, handy general-purpose piece meant to be suitable both for most big game hunting and as a lone scout/sniper's weapon in war.

Chambered usually in .308 Win, the scout rifle's most obvious feature is a low-power scope sight mounted low with its ocular lens just ahead of the action port. This enables the shooter to see around it, gaining in effect an unobstructed field of view, gives unhindered access to the action and permits the use of stripper clips.

The other concept is a “crumpler” for large, dangerous game, nicknamed “Baby” after Sir Samuel Baker's fearsome “child of a cannon” that threw a half-pound explosive shell. It is a short, heavy, extended-magazine bolt-action (preferably the Brno ZKK 602) fitted with a ghost-ring aperture sight and chambered to the .460 G&A wildcat cartridge.

Based on the .404 Jeffery case, this round propels a 500-gr. bullet to 2400 f.p.s. from a 21" barrel, and I have no doubt it will do an expeditious job on anything if directed properly. Cooper used “Baby” to crumple up a great buffalo bull in Botswana on his 70th birthday.

The American Pistol Institute at Gunsite has been a very successful shooting school, with up to 700 students a year. In the past, students received part of their instruction from Jeff Cooper. This is no longer the case.

Having passed his three-score-and-ten, Cooper says he wanted to divest himself of some of the day-to-day chores of running Gunsite. Thus, Gunsite was sold early last year to a former student and instructor with the understanding, according to Cooper, that he would remain in charge—in other words he would sell the ship but stay on as skipper. I know of a couple of instances where that sort of arrangement has worked out, but mostly it does not.

Gunsite, says Cooper, allowed him to teach what he believed in, and to make self-defense techniques available to all who deserved them. Besides, it was fun, and what he wanted to do. He now regards the sale as mistake.

A man of many parts is Jeff Cooper, apart from being the guru of the combat pistol, warrior (as all true men are at bottom), Marine officer, spook, swordsman, bon vivant, historian, scholar, adjunct professor of police science, connoisseur of fast cars, expert rifleman and big game hunter, adventurer (“peril— not variety—is the true spice of life”), philosopher, NRA director, a superb writer and author with a wonderful command of the language, father and grandfather, husband to one of the most gracious, charming and delightful of ladies (doubt not her core of steel, though— else how could she have managed Jeff for more than 50 years?), a seeker of excellence whose creed is Honor, Duty, Country, a man with a great gusto for life, and, perhaps above all, a teacher.

He is a strong-willed person who expresses his opinions confidently, defends them with verve and erudition in debate, suffers not fools, and scorns “political correctness.” Consequently he has deeply offended some people, mostly of the left. On the other hand, he has also attracted an almost cultist group of true believers for whom his every pronouncement is The Word. I am not one of them.

Cooper is a very human man, and thus by definition grievously prone to sin and error (I will wager, though, that he is right more often than most of his detractors). I disagree with Cooper about many things, such as the comparative effectiveness of various cartridges and bullets, magazine cut-offs, the best form of shooting sling, and other matters. But these are trivial; when it comes to values, philosophies of life, what is a man, and what the Republic should stand for, we are on the same side. Warts and all I like and admire Cooper a lot.

Be all that as it may, he is truly the father of the modern technique of the pistol. Others helped evolve it—and it continues to evolve—but he put it all together, promoted it, and taught it. No one since Samuel Colt has had a greater impact on practical pistolcraft than Col. Jeff Cooper.