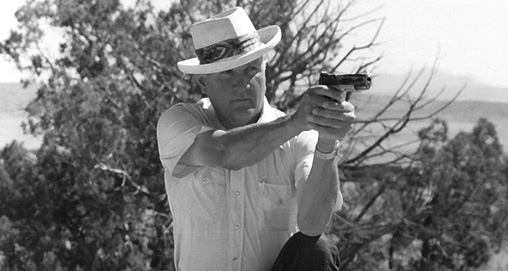

John Dean Cooper—“Jeff” to one and all—stands alone and unchallenged as the most influential individual to ever hold forth on small arms doctrine and technique.

Never one to lean on false modesty, Cooper avowed that he was the “fountainhead” of shooting doctrine, and indeed he was. Cooper single-handedly changed the entire methodology for small arms in all branches of the U.S. military. He modernized Applegate’s outmoded “hip shooting” and “point shooting” techniques with a thoroughly new method. In the process, he transformed law enforcement handgun training nationwide, from the FBI Academy to Mayberry RFD.

Some readers might not know the background of Jeff Cooper. He was born to a well-to-do family in California in 1920. He earned a political science degree from Stanford University in 1941 and, later in 1941, he also earned an honor graduate commission in the U.S. Marine Corps a few months prior to the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. Jeff fought in the bloody Pacific Theatre during World War II. He also served in Korea, eventually rising to the rank of Lt. Colonel.

After the war, in Big Bear, Calif., he founded the first practical shooting club and later organized other clubs that eventually became the Southwest Combat Pistol League. There, he and other devotees of the craft of shooting with speed and accuracy held “leather slap” matches in which the goal was to draw and fire a shot at “combat distance,” timed with a stopwatch. Of course, anyone who competes in anything from tiddlywinks to yachting always looks for an edge over his adversaries, and Cooper was no exception.

Cooper observed that one of his competitors, Jack Weaver, used a peculiar shooting stance that enabled Weaver to fire his double-action revolver surprisingly fast—yet accurately. (Weaver was one of the few wheelgunners in the League; most favored the M1911.) Cooper digested Weaver’s stance of a bent elbow on the support arm and refined it for the 1911. He named it the Weaver Stance and advocated it above any other technique when he later became a full-time shooting instructor.

That development came in 1976 when Cooper founded Gunsite, a ranch in northern Arizona dedicated to propagating the full body of knowledge he had, by now, codified as the “Modern Technique,” based largely on what he’d learned at those Big Bear “leather slaps.”

Simple to describe yet multi-faceted in its nuances, the Modern Technique begins with four rules of safe gun handling. We’ve all seen these very same rules, in precisely the wording Cooper originally articulated, displayed on signs in police shooting ranges, military ranges, civilian ranges, gun shops and even on business cards. Every gun owner should commit them to memory:

Rule One: All guns are always loaded.

Rule Two: Never let the muzzle cover anything which you are not willing to destroy.

Rule Three: Keep your finger off the trigger until your sights are on the target.

Rule Four: Always be sure of your target.

I regularly see these rules in practice in the newspaper. Look at almost any photo of our soldiers in Iraq or Afghanistan and you’ll see fingers straight and outside the trigger guard—Rule Three.

In the Navy SEALs today, Cooper’s rules are so sacrosanct that a single violation of Rule Three can be enough to get you kicked out of a platoon and sent down to ride a desk. At the SOTG training facility on Camp Pendleton, Force Recon Marines are allowed precisely one violation of Rule Three; on the second, they’re kicked back into a regular infantry company. Those are just two indications of how powerful Cooper’s rules have become.

Remember the scene in Black Hawk Down? A brash D-Boy is castigated by an officer in the chow hall for having the safety off on his M16. “Here’s my safety,” says the cocksure sergeant, holding up his trigger finger. Rule Three indeed!

After Cooper’s exquisitely succinct safety rules, the Modern Technique moves on to shooting principles, all of which are based upon the vital exigencies of shooting to save your life with a handgun. The Modern Technique applies to handguns in life-or-death situations, not target shooting. (Jeff also codified rifle and shotgun techniques, but the Modern Technique refers specifically to a defensive handgun.) Cooper’s principles are not in particular order because none supersedes another; they’re all equally vital.

The first principle is called the “flash sight picture.” Cooper advocated that sight alignment during a crisis must be acquired instantaneously as the pistol comes on target. Simultaneously (and in accordance with Rule Three), the trigger finger moves on to the trigger. A flash sight picture can sometimes involve only superimposing the slide over the target when the range is at arm’s length; other times, the front sight must be crystal clear in the rear notch. Learning to recognize an appropriate sight picture—a flash sight picture—is the hardest aspect of the Modern Technique to learn. Oh yes, and you need to shoot with both eyes open.

The second principle is the “compressed surprise break.” This was a whole new approach to trigger control. Cooper knew that anytime a trigger is “jerked,” it disturbs the sight picture to learn even a flash sight picture to learn so it’s imperative to compress the trigger without flinching, or otherwise disturbing sight alignment. Existing theory, all based on bulls-eye targets, held that the trigger must be pressed very slowly until the gun fires “by itself” and thus “surprises” the shooter, preventing him from flinching.

Cooper recognized the inherent validity of this target-shooting theory, but, at the same time, he knew that in a gunfight, you have to take your time quickly. Accordingly, he taught a trigger manipulation technique—the compressed surprise break—in which time, not the trigger, is compressed. Squeeze and get a surprise break, but do it now!

The third principle is the “controlled pair,” two shots fired in quick succession—the double-tap. The Colonel had seen combat in the Pacific and in Korea, and he knew first-hand that a handgun, even the venerable .45 ACP Government Model which he championed more than any other, is not a 100-percent fight stopper with a single round. Two shots fired almost as one is required to assure maximum incapacitation of a threat. As an aside, he preferred the term “hammer” to “double-tap” for firing what he formally termed a controlled pair.

The interval between shots is solely dictated by your flash sight picture. When you see the front sight sharply on the target as the gun recoils, or recovers from recoil, that’s the time for a second compressed surprise break. It can be “bambam” at 5 yards or “bam… bam” at 25 yards.

Cooper’s adaptation of Jack Weaver’s bent-elbow stance is the fourth principle of the Modern Technique. I need hardly describe the Weaver Stance—its world-wide familiarity is another testament to Jeff’s unparalleled influence on shooting. The key is isometric tension between the support arm and shooting arm, creating a shock-absorber effect to master recoil and, more importantly, muzzle rise.

Another principle included in the Modern Technique is Cooper’s uncannily lucid breakdown of how to draw a handgun from a holster. He called it the “five-step draw” and it too is now standard throughout law enforcement and the shooting world. It’s as safe as it is fast.

Cooper formulated many other handgun techniques from the “tap-rack-bang” malfunction drill to how to shoot a Mozambique drill (two to the body, one to the head). His creation of the International Practical Shooting Confederation (IPSC) codified the Modern Technique into sport shooting.

Today, everyone from Special Forces operators to Force Recon Marines to Navy SEALs utilize Jeff’s Modern Technique, or a variation thereof. No one has ever done so much for so many as John Dean Cooper.