This article appeared originally in the February 2007 issue of American Rifleman. To subscribe to the magazine, visit the NRA membership page and select American Rifleman as your member magazine.

The ground was dry and dust trailed behind me as I slowly walked the 100 yards along the bullet’s path. My hand gripped the rifle’s battered stock, and I thought about how much sweat the walnut had absorbed over the years. I thought about how many adrenalin-charged hands had manipulated the rifle’s bolt. Men who were afraid had carried, fired and relied on this rifle to keep them breathing as they faced mbogo (Cape buffalo) and other potentially dangerous encounters. This rifle had ‘been there and done that’ many times.

—Richard Mann

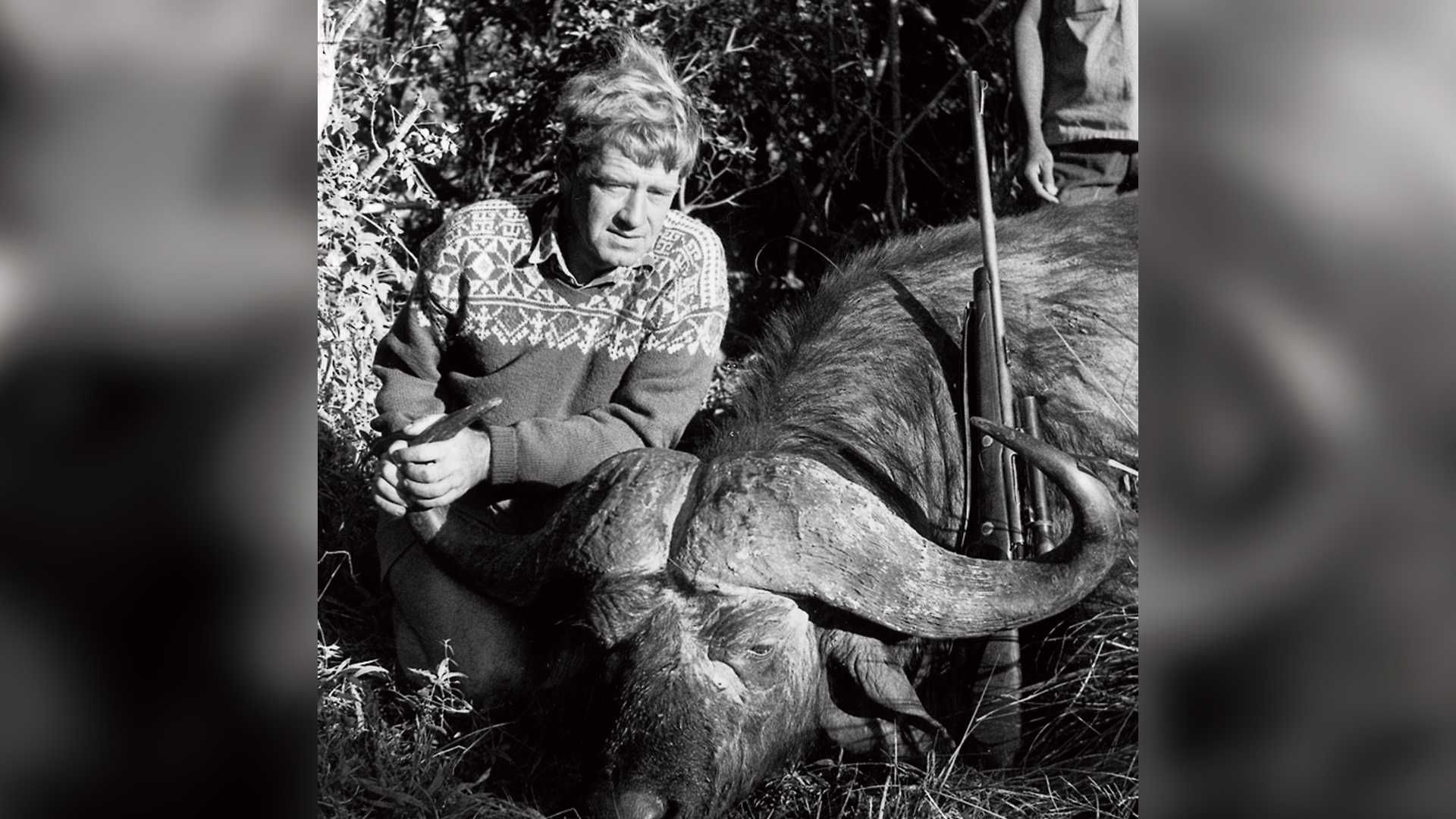

In addition to having been a field editor of American Rifleman, the late Finn Aagaard worked as a professional hunter in Kenya from 1970 to 1977, and during that time, he owned and used a number of rifles. But he was especially partial to the .375 H&H cartridge in general and to one rifle in particular: a battered and scarred pre-’64 Winchester Model 70 in .375 H&H. Finn kept extensive diaries on every rifle that he owned, and his family was kind enough to allow me to examine not only the diary of his favorite .375, but all of his notes and journals.

The rifle, serial number 70146, was purchased by Finn on Dec. 29, 1969, for 1,200 Kenyan shillings; it had been out on loan to him since Nov. 25. He noted its price was “excessive.” Immediately after acquiring it, Finn worked over the trigger, and four months later, he fitted it to a Winchester Super Grade stock he acquired from his associate, Joe Cheffings. The rifle’s diary indicates that what appeared to be cross-bolts in the new stock were nothing more than “plastic plugs.” Finn replaced the plugs with stove bolts set in resin and bedded the stock. He selected the Super Grade stock because the higher comb was more suited to scope use, as Finn strongly believed that a low-power riflescope was superior to open sights for all African game. He mounted a Weaver K 2.5X fixed power model to the Winchester.

Finn once wrote, “I believe you should have scopes on all your African rifles, even the ‘heavies.’ In the dull light of an early dawn for example, with a black buffalo standing in dark bush 100 yards away across a glade, it is far easier to make out exactly where to place your shot with a good low-powered scope than with any form of iron sight.” He also remarked that on this particular rifle, he never used the open sights to fire a single shot at a game animal, stating, “There is nothing that (iron sights) will do at any range, including charges, that a low-power scope won’t do as well or better.”

In a June 17, 1970, letter to Winchester, Finn described the .375 as a “ … very accurate, reliable and lucky rifle. … Shortly after I got it, I killed 2 stock raiding lions with it, one after the other with just one 270 grn power-point each.” He added, “ … this rifle has become my pet of pets,” and he asked if Winchester could identify when it was made. Winchester responded that the rifle was probably made between 1947 and 1948.

A journal entry dated Dec. 12, 1969, for shot numbers 24 and 25 from the rifle, only briefly mentions the lions: “2 Lions (male) 2 x 270 PP (Winchester Power Point) at elephant carcass.”

Finn used the rifle to kill four elephants and collaborated with clients on an additional four. One of these was a 60-lb. tusker taken on May 2, 1973, and the diary entry for shots 519, 520 and 521 is as follows: “Pringle Safari Elephant Alec (male), 60 pounds. Charge! 3 handloads. Hornady solids, fired at 14 paces. 1st (1+1 458) brought it down. Started to recover, so 2 more. 1 solid recovered just under skin, just behind left ear—perfect shape.”

Later writings offer some clarification of the incident; “Alec Pringle had the M70 (.375) in his hands when an exasperated bull charged us, meaning every bit of it. Somehow my thumb failed to flick off the safety as the rifle came up, so Alec thumped the jumbo in the head with the .375 at 14 paces, and it was already falling by the time I sorted out the .458 Westley Richards. It started to get up and we both shot again. But it was the .375 that saved our hides, even though the bullet missed the brain.” Another interesting comment in the diary lists the ammunition used as “handloads.”

Handloading was a crime punishable by death in Kenya, and Finn did not handload until he moved to the States. We can only speculate that the ammo Pringle was using was brought to Kenya with him.

During the 2006 Houston Safari Club show, I visited with Dick Teal, a former director of that organization. Teal hunted with Finn in June 1975 while Finn was operating Bateleur Safaris out of Nairobi, Kenya. Dick had been very impressed with Finn’s demeanor, knowledge of game and his shooting skill. Teal told me he had wounded a zebra, and after following the spoor for nearly three miles, they spotted it running out past 200 yds. Finn told Teal to shoot, but Dick declined and asked Finn to finish the wounded animal. Finn sat down, threw the .375 across his knees and dropped the Zebra at what Teal offered was near 300 paces. I checked Finn’s diary, and under the date of June 19, 1975, which recorded shots number 730 and 731, he wrote: “At Dick Teal’s zebra—2 x PP (Winchester Power Point), (at) 250y (yards) Both hits, first root of tail, put hind end down, second shoulder with sling from sit—tight sling a definite aid. (This one is U.S. Army, dated 1918!!)”

Teal also told of the difficulties they experienced on that safari trying to deal with the paper-thin tires on the vehicles, and he also commented that if Finn, who normally wore shorts, showed up in the morning wearing blue jeans, they knew they were in for a hard day.

On May 20, 1977, when hunting was banned in Kenya, Finn listed the total animals taken with this rifle at 125. The detailed chart also showed the number of animals he had collaborated on with clients, as well as the nine that were hit and lost (see below). At that time, there had been 944 shots fired from the rifle, and most appropriately, the last three were solids fired into Finn’s favorite game animal, a Cape buffalo. On April 3, 1977, Finn wrote in his journal: “3 solids @ 100y. First into shoulder @ halfway up, smashed opposite scapula, not found. Buff went down, kicked a bit, got up, turned to face us. 2nd center of chest, dropped. 3rd safety shot in neck.”

Finn was a big fan of the .375, and he once wrote “Holland’s .375 Belted Rimless Magnum Nitro Express (a mouthful its users shorten to simply ‘the three-seven-five’) is such a useful and versatile big game cartridge that nothing else that has appeared in the last 70 years since its birth can quite match it.” He went on to say: “ … when serious hunting was afoot, I somehow always seemed to automatically pick up the .375.”

After Finn became a U.S. citizen, he lived in Texas. He kept his pet Model 70 and started reloading, something he had long wanted to do. He further expanded the log book on his favorite rifle to include extensive handloading data. Finn was a very astute student of the bullet, and the journal also contained exhaustive bullet-testing results.

I never had the opportunity to meet Finn, but kneeling in the Texas heat, holding his rifle and examining the steel plate with two splatters where the heavy slug had smacked it, a chill crept up my spine. I have held a few historic rifles in my hands, but none touched my hunter’s heart like this one. I thought of the excitement that the rifle had seen, of the smiles it had made possible and about how it had kept a hard-working man’s family fed.

This rifle had battled it out with 62 buffalo, either in Finn’s hands or in the hands of his clients, and only seven had not been recovered. It had spent eight years in the wilds of Kenya, and it looked it. The metal was nearly devoid of bluing, and the stock looked like a fence post, but you can be sure every mark, every scratch and every gouge got there honestly. Oh, if a rifle could talk? This one does through Finn’s diaries and journals, and what an amazing tale it tells.

Finn’s Journals

Finn’s journals are amazingly accurate and complete. Not only did he record the animal, shot placement, bullet and bullet performance, but he also listed all shots fired as a signal to other hunters and at targets. These records were not just kept for his favorite .375 Winchester. Finn kept a log book for every rifle he ever owned. The journal for a 7x64 mm Breneke is just as thick and is full of interesting entries, too.

Finn Aagaard’s Model 70 in .375 H&H rests on the diary that he used to record his experiences with it. Few rifles have been shot as extensively in the game fields, and even fewer have had their histories so meticulously preserved in writing.

For more than a decade, American Rifleman readers were privileged to read Finn’s writings and learn from his experiences. He left us all too soon, and there was so much more we could have learned. Much of that knowledge and history exists in his own handwriting in old bound ledgers and spiral notebooks.

—Richard Mann

A special thanks to the Aagaard family for its assistance in the preparation of this article.—The Eds.