The practice of hunting in England at the time the American colonies were settled was legally restricted to the gentry. Virtually all of the land was owned in large parcels by the wealthy, who preserved them from generation to generation by bequeathing their entire estates intact to the oldest son through the law of primogeniture. To protect these fields and woodlands from poachers, gamekeepers were employed who patrolled the properties and provided selective hunting for the owners. By law, no one was allowed to own a gun unless he possessed substantial freehold property or was given special permission. Thus, legal shooting was not even a choice for the average citizen. By the 1740s this restrictive practice led to hunting being considered a symbol of wealth, and field shooting “on the wing” had become a popular sport for the well-to-do.

In North America, however, land was readily available, and possession of guns was universal as hunting with firearms was a primary means of survival. Rural homes depended on arms to help feed their large families, as well as to provide physical protection and fulfill local militia demands. The heavily wooded terrain of the New World, in turn, provided a bounty of game ranging from turkeys, geese, ducks and game birds to the larger deer, bear, elk and moose. In order to take advantage of this, the provincials employed various combinations of ball, buckshot, or buck and ball in smoothbore flintlock fowlers which were the forerunners of today’s shotguns. (The rifles developed in Western settlements are not included here.)

These arms generally had long barrels averaging 44" to 60" to permit the full powder charge to burn effectively and to provide an extended sight radius. Such lengths may seem unwieldy, but the dense overhead canopy of the virgin forests permitted far less undergrowth than that encountered in today’s second growth woodlands. The typical gunstocks were walnut, maple or cherry and included a high-raised comb, plus a fore-end that reached to the muzzle—which frequently had the wood cut back 3" to 4" and a barrel stud added to mount a socket bayonet for military service. Second sights were rare; the front blade was usually supplemented by a groove filed into the breech tang as the rear-aiming guide. Sling swivels, too, were omitted as the arms were intended to be hand-carried for instant use.

While many arms were supplied from abroad, those created or repaired by Americans often employed a mixture of parts reused from prior guns or imported as individual components. The patterns varied by geographical region and evolved toward lighter designs as the tree cover gave way to open land and smaller game. In the final analysis, however, it was the man himself who made the difference. Hunting has always been fundamental to our enduring frontier spirit, and this review of its Colonial beginnings reveals how America’s ancestors adapted to many of the same challenges facing modern hunters.

French Influence

The settlers of New France depended primarily on the exporting of furs, which required preservation of the existing forests. The Ministry of the Marine controlled their colonizing of the New World and contracted in France for the arms used both by civilians and the military.

Their typical hunter’s gun (fusil de chasse) was light and well balanced to satisfy the woodsmen (voyageurs, coureurs de bois) and Indian allies. Most were made in Tulle or St. Etienne and averaged 60" in length with a 441⁄2" pinned octagonal/round barrel (.62 caliber) on a walnut stock featuring a high comb, a Roman nose butt, plus raised carving and a fore-end extending to the muzzle. A flat/beveled lock was held by two screws. The iron furniture, in turn, included rolled sheet iron thimbles which secured a wooden ramrod. Its weight averaged 6-7 lbs. This was a design well suited for use in rough terrain and was also prized by many English Colonists.

In addition, the French produced a more decorated firearm for Indian leaders (fusil fin de chasse) as well as a cheaper version for the fur trade (fusil de traite). This important supply of hunting guns ceased following France’s withdrawal from North America at the end of the French and Indian War in 1763.

English Hunting Guns

Unlike New France, the British Colonies were established to send raw materials back to the mother country and then to serve as a market for its finished goods. This led to the clearing of land to create villages and roads, which copied the established culture of Europe and favored the Old World’s guns patterns.

North American settlers during the 17th and 18th centuries were first supplied with long, heavy military and civilian shoulder arms that were obsolete but available and inexpensive in Britain. Contrary to the French practice, however, the English Colonists could order firearms of their own choice from private gunmaking centers such as London, Birmingham and Liege (Belgium). This flexibility, spurred by demands from their lucrative fur trade—which was competing against French arms—led to lighter and less unwieldy hunting guns by 1730.

The gunsmiths of Britain produced some elegant fowlers during this period, but since gun ownership and hunting were restricted to the wealthy, their volume was limited. A wide range of less expensive functional designs, however, was also being manufactured but, of necessity, was intended for sale abroad (especially to the American Colonists) and few survive in Britain today.

These circa 1730-1770 export fowlers were light, well-balanced patterns with pinned smoothbore barrels usually 44" to 50" in length and .60 to .70 caliber. Their walnut stocks retained a comb above a banister rail but replaced the curved Roman nose with a straight sloping bottom profile and included raised carving around the barrel tang, lock and sideplate. The two-screw locks were either convex or flat and had a swan’s neck cock plus a rounded pan. They were popular among Americans, and their brass furniture components were also shipped separately for use on arms produced in the Colonies. Many of these fowlers are found with their barrels cut short by hunters to facilitate use in rough terrain.

The North West Gun

Following the end of the French & Indian War (1754-1763), Britain’s control of the former lands of New France created an escalated demand for hunting/ trade firearms. The growing Hudson’s Bay Company helped to fill this need by expanding production of its famous “North West” (“Mackinaw”) trade gun. Although developed for the fur business in the early 1700s, this shortened, inexpensive pattern, which weighed 5 to 6 lbs., was adopted by many Indians and white hunters and would continue to be used in remote areas of North America well into the 20th century with both flint and percussion ignition.

Its walnut stock mounted and pinned a smoothbore octagonal/round barrel 36" to 48" long (.55 to .66 caliber). The three-screw lock had a swan’s neck cock and rounded pan. It normally bore the name of the arm’s maker, but by the 18th century’s last quarter was usually stamped with a seated fox figure facing left (Hudson’s Bay Co.) or to the right (North West Co.). A distinctive deep trigger guard bow was earlier associated by collectors with the ability to shoot using a mittened hand, but recent research has established that it originated to accommodate a two-finger trigger pull.

American Patterns

To the American Colonists the hunting gun was his primary food source or the critical supplement to an unreliable crop yield.

Although many of the available firearms were imports, substantial numbers were produced by local gunsmiths who followed regional preferences and often used European made components. The gun sizes and capabilities, in turn, changed as the large animals followed the tree line moving westward.

By the early 1700s, the initial obsolete commercial and military arms were being replaced by a variety of forms including copies of the French fusil de chasse, club butts, light English patterns, assembled odd components, fur trade designs, graceful New England fowlers, and even long, heavy “Hudson Valley” or “punt” guns designed to deliver massive buckshot loads at waterfowl on the surface.

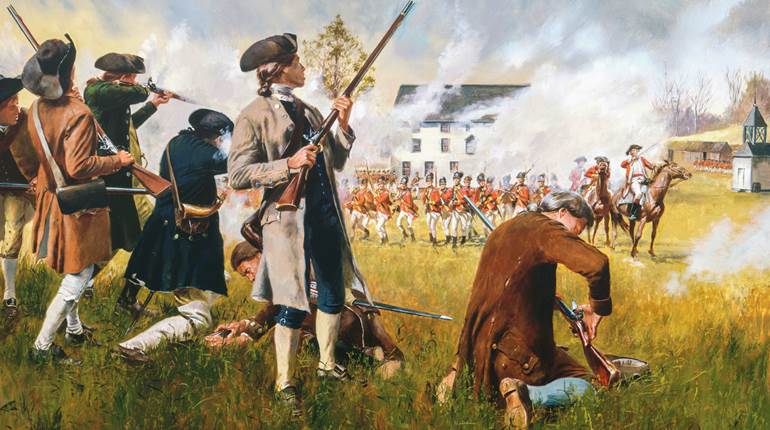

Because of their availability, these various arms also served as the primary arms for the American armed forces during the early years of the Revolutionary War. The original guns shown in the article are considered representative of this diversity.

Examples of Colonial-era Hunting Guns

American Hunting Gun, c. 1730-1760

In addition to importing compete firearms, the Colonists also ordered parts for assembling and repairing guns themselves. This long fowler with its American cherry stock having a fore-end reaching to the muzzle and a Roman nose butt, is fitted with typical period components from the mother country. Its flat trade lock displays a panoply of arms on the tail, as well as a gooseneck cock. A generic game bird, in turn, is engraved on the stepped butt tang and the pinned octagonal/round smoothbore barrel bears two circa 1702 London Gunmakers Company proofs plus the maker Richard Wilson’s stamp (*/rw”). The popular English trigger guard form included a “tulip” front terminal and the snowflake design on its trigger bow. An engraved triangular sideplate adds a rear wood screw.

Length: 66 3⁄4"

Lock: 6"x1 1⁄8"

Butt Tang: 4"

Furniture: Brass

Barrel: 50 3⁄4", .67 caliber

Trigger Guard: 10"

Sideplate: 5 3⁄4"

Weight: 8.3 lbs.

Hunting Fowler, c. 1730-1760

The profile of this long, lean fowler has a close resemblance to the French Fusil de Chasse. It was a popular form in the American Colonies, which provided the balance and light weight so appreciated by hunters. The walnut stock reaches from a Roman nose butt to the muzzle and holds a wooden rammer in three cast brass pipes. English-made components include a rounded two-screw lock signed by its maker, “heckstall” (no outer bridle), a stepped butt tang, and a common export trigger guard that ends in a pointed front finial and bears a snowflake design on the trigger bow. Its sideplate is a colorful serpent form with incised decorations. The 463⁄8" (.68-cal.) pinned round barrel is octagonal for 81⁄2”.

Length: 61 1⁄2"

Lock: 6"x1 1⁄8"

Butt Tang: 4 1⁄4"

Furniture: Brass

Barrel: 46 3⁄8", .69 caliber

Trigger Guard: 9 3⁄4"

Sideplate: 5 1⁄2"

Weight: 6.8 lbs.

English Commercial Hunting Fowler, c. 1750-1760

Beyond supplying the narrow market for hunting guns limited to landowners in England, the British maker developed field-grade, lightweight, affordable fowlers for mass export by 1730 to replace the clumsy obsolete arms previously sent to the Colonies. This is a typical example of these well-balanced, popular arms. The walnut stock has a banister rail butt with a straight bottom profile replacing the earlier Roman nose. It then reaches to the muzzle of a 481⁄4" (.62-cal.) round/octagonal pinned barrel (private Tower proofs). The rounded trade lock is marked, “galton” (a Birmingham maker) and adds an exterior bridle. Other furniture includes a stepped butt tang (game bird engraving), a double-ended escutcheon, a triangular sideplate (21⁄2 screws), a tulip-headed trigger guard and fan carving around the barrel tang.

Length: 63 3⁄4"

Lock: 61⁄8"x1 1⁄8"

Butt Tang: 4 1⁄8"

Furniture: Brass

Barrel: 48 1⁄4", .62 caliber

Trigger Guard: 10"

Sideplate: 5 3⁄4"

Weight: 6.7 lbs.

English North West Trade Gun, c. 1730-1756

When France exited North America in 1763 after the French and Indian War, Britain had to provide firearms to the hunters and fur traders of that immense new territory. Much of the void was filled by this light, inexpensive trade pattern already developed by The Hudson’s Bay Company. Known as the North West gun, it became a favorite of Indian and white woodsmen into the 20th Century. Its early features became standardized as trademarks. They included: a three screw rounded lock without bridles, a serpent sideplate, a nailed lobe-ended flat buttplate, ribbed pipes for a wooden ramrod, a deep trigger bow, a slender walnut stock and a round/octagonal smoothbore barrel (3 to 4 ft.; front sight only.) “wilson” (London’s gunmaker, Richard Wilson) appears on the lock’s tail plus his “*/rw” stamp on the breech.

Length: 52 1⁄8"

Lock: 6"x1 1⁄8"

Butt Tang: 2 1⁄4"

Furniture: Brass

Barrel: 36 3⁄4", .66 caliber

Trigger Guard: 8 7⁄8"

Sideplate: 6"

Weight: 5.2 lbs.

Extras

Locks

From top down:

(1.) The flat, beveled-edge lock on a French Fusil de Chasse (c. 1730-1750).

(2.) A captured French M. 1728 musket lock re-used on an American striped maple stock.

(3.) A flat British export pattern having a distinctive right angle in the lockplate forward of the frizzen and a panoply of arms engraved on its tail (c. 1730-1760).

(4.) A flat American “banana” lock (c. 1745-1780).

(5.) A popular English convex commercial lock with its round pan (note the typical British split trigger loop).

(6.) An elongated American pattern by John Page of Preston, Conn., that includes a period floral engraving.

(7.) The simple North West Trade Gun rounded lock omits both bridles and is marked “wilson” on the tail (note the distinctive deep trigger bow).

Sideplates

From top down:

(1.) An American frugal hunting gun omits the side plate.

(2.) The typical French Fusil de Chasse L-shaped form with its oval center.

(3.)The popular British triangular plate includes a short rear wood screw and slashed lines across its tail (c. 1730-1760).

(4.) An English panoply design mounted on an American striped maple stock (c. 1740-1760).

(5.) An expansive European pattern (c. 1745-1780) plus a sheet-brass, broken-wrist repair.

(6.) An engraved flat version of the popular serpent side plate (c. 1730-1760).

(7.) The North West Gun’s traditional three-screw raised surface serpent design.

Hunting Ammunition

It is evident from the variety of buck and ball sizes combined in the same bullet molds that the 18th-Century hunter relied on mixed loads according to his prey and the prevailing conditions. Unlike the trained soldier who shot a round ball .04 to .06 caliber smaller than the bore to allow for blackpowder fouling (he would normally fire in excess of 60 rounds in battle), the hunter, limited to one or two shots against most game, would load his smoothbore with a round bullet wrapped in greased cloth or thin leather for large animals. This tightly fitted “patched” ball could easily make a 10" group within the normal range of 30 to 60 yds.

The mixture of shot sizes depended on the target and the shooter. For example, NRA Life member Dick Weller of Earlville, N.Y., who hunts with original 18th century smoothbore flintlocks, has been successful with the 0.658" to 0.760" round balls employing 116- to 151-gr. FFg charges on deer, moose and bear out to 60 yds. It should be kept in mind that an individual in the forest for an extended period of time was helpless without his supply of lead and powder. The lead bullets were usually cut out of dead game for recasting, and the powder charge would be minimized for smaller targets at closer ranges. To be flexible, many of the early powder measures were calibrated for only half of a full load.

Although hunting was considered a sport among wealthy Colonists, it is visions of the typical early American in deep woods stalking game to bring his family through the winter or penetrating the frontier relying on the hunting gun for survival that brings to life our country’s history during those formative years. It is a story of continuous adventures retold by the actual arms they carried now in collectors’ hands or by the woodland treks of today’s muzzleloading hunters who re-create the original arms, accoutrements and clothing to match wits with real game that help us appreciate the amazing accomplishments of those solitary individuals who forged America’s path to greatness.

This feature article appeared originally in the May 2004 issue of American Rifleman. To subscribe to the magazine, visit the NRA membership page and select American Rifleman as your member magazine.