Bullet science has come a long way since Nebraska businessman Joyce W. Hornady founded his namesake company, and perhaps more to the point, because he did so. Rather than continue selling Speer component bullets via mail order—at first moonlighting from his wartime job at Cornhusker Army Ammunition plant, then while running a sporting-goods storefront—he decided in the spring of 1949 to go all-in on making his own. After announcing a single 150-grain, .30-cal. offering in The American Rifleman’s May classifieds, near-monthly follow-on ads tracked Year One growth to 13 product offerings across five different calibers and touted groups as small as 1/4".

From that unassuming start, Hornady Mfg. has blazed a unique trail to the top rank of America’s shooting industry, though not without overcoming some daunting setbacks. Celebrating its impactful three-quarters of a century, this hometown success story remains in family hands, those of the founder’s son, Steve Hornady (CEO), and grandson, Jason Hornady (VP of Sales and Marketing). True to form, they’ve never strayed from Papa Hornady’s original ambition to make better bullets available to America’s most avid marksmen. What’s changed—many times over—is what makes bullets better. With that as its compass, Hornady is currently leading the march to ballistic performance that is re-defining what is possible, practical and ethical.

“As practically everyone reading this knows, we’ve been incredibly busy the last 75 years,” wrote Steve and Jason Hornady in their company’s 2024 catalog. “Our customers deserve a lot of the credit, not only for supporting Hornady, but also because many of our most successful products were born of customer suggestions and requests. Thank you for believing in us, motivating us and inspiring us.”

Case Forming

Case Forming

Talk about low-key: Joyce Hornady worked out of his Grand Island, Neb., basement before launching production with a single used press in a rented garage. Badly underfunded, first-year sales amounted to less than $10,000. Even so, there was no letup in Hornady advertising in Rifleman, including a July 1950 spot professing, “We could not anticipate the demand … and not enough were manufactured. They are back again in improved form, and production this year will be many times greater.” When sales tripled over the following year, things looked better. But with the Korean War came shortages of materials, and though Hornady held on in the bullet trade, the company was forced to take on other work. One deal, a government contract to fabricate refrigerant condenser cans, ultimately brought long-term dividends. “After the war, the can material and the technology developed to produce them were utilized to make ultra-thin copper jackets for varmint bullets,” notes a corporate video. Some six decades later, Chief Ballistician Dave Emary would cite institutional thin-jacket expertise during a sit-down with NRA Publications editors to introduce cutting-edge ELD Match bullets.

Cashing in on America’s red-hot postwar economy, Hornady re-located in 1958 to a newly built 8,000 sq.-ft. factory on the west side of town, and in two years added an underground 200-yard test tunnel and lab. Hornady headquarters and manufacturing facilities are still there.

New products were practically monthly occurrences as the Nebraskans hustled to supply bullet styles in every caliber and weight loaded by their varmint- and big-game hunting customers. The initial spire points were soon augmented by heavy-for-caliber round-nose slugs popular among hunters seeking a “brush-busting” stopper.

Boosting Hornady’s stature was 1961’s secant ogive (S/O) bullet, featuring a “longer and sharper point” than the pencil-like spire points, thus retaining greater velocity downrange. “Comparative ballistics prove the increased efficiency of this new shape,” stated Hornady advertising. The proof, conveyed in tables pitting various .30-cal. 180-grain loads at 500 yards, showed 7.5 percent more velocity, 23 percent less 10-m.p.h. crosswind deflection and 14.5 percent more retained energy compared to the conventional spire point.

In 1964, Hornady created the Frontier Cartridge Co., which “remanufactured ammunition made from surplus brass.” More succinctly, Frontier ammunition would utilize previously fired cases as a means to get Hornady bullets into the hands of more shooters. How many more is an interesting question, and if you follow the bread crumbs to the 2020s, those hands number in the tens of millions. American Rifleman made mention in 1979 that Frontier-headstamped cartridges, in both rifle and handgun cartridges, “sell somewhat below those of the ‘big three,’” but the coverage drew attention to a controlled-expansion hunting bullet, the InterLock, whose stout jacket featured an inner ridge that locked it to a hardened-lead core, and it is still going strong in multiple ammunition lines. The 1971 acquisition of Pacific Tool Co. fortified Hornady’s stature among its handloading core. Highly regarded Pacific presses, tools and accessories were much in demand, and Hornady proudly shared the news in a Rifleman ad headlined, “Some people don’t even realize we’re married.”

Both ventures are still going strong, though their brand names have since reverted to Hornady. Reloading tools and accessories were formerly manufactured at the headquarters campus alongside bullet and ammo production, but, as 21st century ammunition demand surged to unprecedented levels, the tool and accessory operation was moved to a nearby former automotive-parts plant. The DNA lives on however—today’s top-selling Hornady 366 progressive shotshell loader is an update of the old Pacific DL-366. And nowadays, the Frontier name is back on a line of swaged-lead handgun component bullets.

Regrouping

Regrouping

Hornady Mfg.’s rise was rocked by a tragic accident in January 1981. Flying to the SHOT Show in New Orleans, the company plane crashed while landing in heavy fog. Killed in the crash were Joyce Hornady, age 73, engineer Edward Heers, 34, and James Garber, 29, a customer service rep. “We talked about selling,” Steve Hornady said, recalling the aftermath with grieving family members. “I was 31 and had been an employee for about 10 years, mostly on Pacific Tool and in advertising. Or, well, as a kid I mowed grass, melted scrap lead and cleaned toilets. But when it came to operations—How do you create a work order? Send it to the floor? Decide what to run next?—I didn’t know. But there were people here who did because it was their jobs. And the factory never stopped, never slowed down except for the funerals. Hard days. Everyone kept going.

“Nominally, I got this chair and this desk, which literally was his desk. We didn’t have anyone else. Mom [Marval Hornady] had been working in accounting, and she continued. A year later, my sister Margaret and her husband, Don David, came over from jobs at Polaroid, where she worked in management, and Don was an engineer, so that was a natural fit,” he remembers.

“Coming into that situation, the first rule, like for a physician, is ‘do no harm.’ So, I basically kept doing what dad had been doing to keep things moving. Luckily, we kept getting orders and kept filling them. With Don and Margy and others, we would talk over ideas and, on occasion, added a new item, but new products weren’t the driving factor they are now, so there were gaps,” the CEO recalls.

“Coming into that situation, the first rule, like for a physician, is ‘do no harm.’ So, I basically kept doing what dad had been doing to keep things moving. Luckily, we kept getting orders and kept filling them. With Don and Margy and others, we would talk over ideas and, on occasion, added a new item, but new products weren’t the driving factor they are now, so there were gaps,” the CEO recalls.

Some 1980s introductions were match bullets designed for high power and silhouette competitors, most of them handloaders. As streamlined ogives and boattails nudged up ballistic coefficients in dominant chamberings like .308 Win. and 7 mm-08 Rem., firing-line debates across the United States pitted red-box Hornadys vs. green-box Sierras. Steve Hornady pressed on much as his father had, strategically focused on strengthening the company on the turf it claimed as its own: premium bullets, underappreciated commercial ammunition and prestige reloading gear. In that vein, his determination to bring all cartridge-case fabrication in-house could not have been more in character.

In the 1990s, “Much of our brass was still coming from competitors, but with sales going wild because of the political climate—Clinton and Sen. [Daniel] Moynihan’s proposed 10,000 percent tax on ammunition—those guys couldn’t make enough to satisfy their own needs,” Steve said. “As our capacity got choked off, we simply had to make it all. Dad felt that would be impossible, but I decided to tool-up and hire guys who knew how to run the machines. We brought in a bunch of [brass] cups and soon were pounding away. It took time—but that gave us what we needed for the future.”

Cartridge Overall Length

As the brass initiative picked up steam, Hornady engineers kept churning out new bullets, many of which caught on quickly and remain popular: eXtreme Terminal Performance (XTP) handgun bullets were “designed to consistently expand and achieve deep terminal penetration at varying velocities”; A-Max (match) and V-Max (varmint) polymer-tipped projectiles featured maximal ogives and boattail bases that boosted ballistic coefficients (BC) and long-range performance; Super Shock Tipped (SST) big-game bullets crossed the InterLock’s controlled-expansion toughness with the sleek, high-BC aerodynamics of the V-Max.

Joining highly regarded Hornady Custom, dealers began stocking Varmint Express, Match and then Light and Heavy Magnum, sub-brands that came as a walk on the wild side for the conservative management.

Follow-on Heavy Magnum loads similarly lifted the 7 mm Rem. Mag. and .300 Win. Mag. cartridges to quasi-Weatherby stats. The unprecedented capability was attributed to a new “cool-burning” propellant that had not previously been used in factory loads and was not available to handloaders. The new lines stuck around until even better technology on the same concept was developed, namely the Superformance line that remains a mainstay in Hornady’s catalog.

What followed was a corporate renaissance.

Even more important than the resulting hardware and software, was an old-hat turn for the family business. In 2006, Jason Hornady, Steve’s son and Joyce’s grandson, came home to Grand Island to join the management team. But before calling nepotism, consider this: Upon returning to the plant where, as a teen, he mowed lawns and did other chores, Jason possessed a 15-year track record in the shooting/outdoor industry. Mostly in sales and marketing, the young man worked for distributors, traveling extensively to meet-ups where dealers and consumers laid bare what clicked and what didn’t. He also headed sales at historic Redfield Optics in Denver at a time when that legacy manufacturer languished under remote ownership. “I grew up walking around this factory with my dad and both grandfathers. I’ve always wanted to be here,” he said. “So, when dad came up with his policy that family members had to go away and work somewhere else for 10 years, I was indignant. But it was valuable because I got to see first-hand what good sales managers looked like and what bad managers looked like. At Redfield I experienced my worst day, but then at Dunkin Lewis [rep group], I was trusted to go in and clean up problems with huge companies, and that was a lot of fun. All told, I worked with nearly 150 different factories, different product lines. I learned a lot.”

Even more important than the resulting hardware and software, was an old-hat turn for the family business. In 2006, Jason Hornady, Steve’s son and Joyce’s grandson, came home to Grand Island to join the management team. But before calling nepotism, consider this: Upon returning to the plant where, as a teen, he mowed lawns and did other chores, Jason possessed a 15-year track record in the shooting/outdoor industry. Mostly in sales and marketing, the young man worked for distributors, traveling extensively to meet-ups where dealers and consumers laid bare what clicked and what didn’t. He also headed sales at historic Redfield Optics in Denver at a time when that legacy manufacturer languished under remote ownership. “I grew up walking around this factory with my dad and both grandfathers. I’ve always wanted to be here,” he said. “So, when dad came up with his policy that family members had to go away and work somewhere else for 10 years, I was indignant. But it was valuable because I got to see first-hand what good sales managers looked like and what bad managers looked like. At Redfield I experienced my worst day, but then at Dunkin Lewis [rep group], I was trusted to go in and clean up problems with huge companies, and that was a lot of fun. All told, I worked with nearly 150 different factories, different product lines. I learned a lot.”

Jason’s arrival coincided with Hornady’s baptism into new cartridge development, which tapped a pipeline that’s still flowing. On the heels of the low-profile .376 Steyr and .450 Marlin came hits like .17 HMR (2002), .204 Ruger (2004), .30 T/C (2006) and .375 Ruger (2006). The peewee HMR (Hornady Magnum Rimfire), the company’s first venture into rimfire, delighted varminters and plinkers and inspired our most striking cover design ever in March 2002, which proclaimed it, “The Little Cartridge That Could.” More came from partnerships with Ruger (.300 RCM and .338 RCM, 2008) and Marlin (.308 Marlin Exp. in 2007 and .338 Marlin Exp. in 2008), and the latter tie-in also spurred the ingenious Flex-Tip (FTX) bullet whose pliant polymer nose made it safe to shoot pointed projectiles in tubular-magazine lever-action rifles. In a single stroke, millions of veteran Marlins, Winchesters and other models were able to digest the resulting LEVERevolution ammunition that improved the class’s trajectories and downrange energy. It came at a time when some expected lever rifles to fade altogether from common use, but instead they’ve made a comeback.

Hit or miss, Hornady kept birthing chamberings, and one of them—the 6.5 mm Creedmoor—is sold nowadays in practically every American gun shop and e-commerce site, plus many more worldwide. It was conceptualized by Hornady ballisticians Dave Emary and Joe Thielen along with former USMC rifle team member Dennis DeMille. With 6.5 mm wildcats then going viral in long-range-precision circles, they sought to balance desired short-action dimensions and mild recoil while prioritizing high retained velocity and flat trajectory. Back at the lab in Grand Island, Emary and Thielen found that extra-long, heavy-for-caliber, high-BC bullets started with a fast rifling twist (1:8" or thereabouts) absolutely hoarded velocity. Case modifications were required to optimize bullet seating depth, and also vital was a new propellent Hornady co-developed with a supplier. According to a 2010 American Rifleman report, the formulation slowed the burn-rate progression to raise the average pressure driving the bullet during its travel through the bore without increasing the peak pressure. Instead of burning more fuel, they made the system more efficient. In that regard, Creedmoor velocity remained supersonic out to about 1,200 yards. Tournament riflemen latched on, then—as word spread about downrange performance, paltry recoil and, best of all, uncanny accuracy—deer hunters, AR enthusiasts, tin-can blasters and others wanted in.

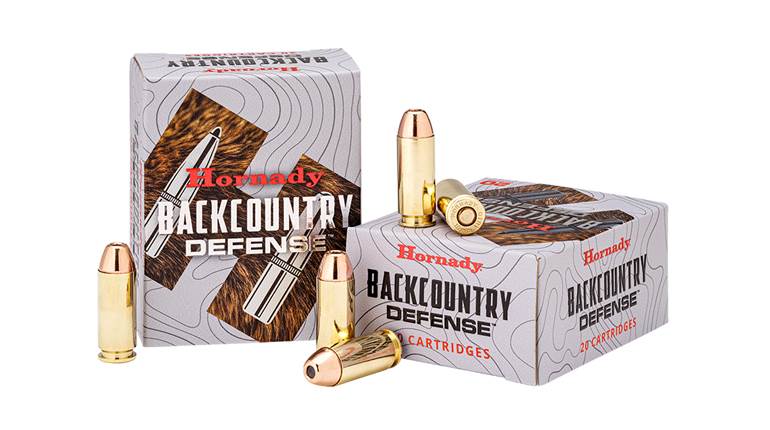

As 21st century Americans grew increasingly proactive in self-defense preparedness, the maker answered the call with Critical Duty and Critical Defense handgun ammunition, as well as Hornady Black for long-gun defenders. The Critical tandem share traits like hi-viz nickel-plated cases, reduced-flash propellants and, most notably, blunted Flex-Tip nose inserts à la LEVERevolution. In this application, FTX bullets govern expansion and prevent the build-up of barrier materials that could deter penetration. Otherwise, we reported, “They have very different roles. Intended for on-duty/patrol/tactical” law-enforcement, Duty’s “goal is to defeat barriers while minimizing over-penetration.” The bullet is fortified by a wide “jacket-to-core” InterLock band. The FBI has since made Critical Duty 9 mm Luger standard-issue.

Conversely, we reported, “Critical Defense is designed for compact, concealable handguns [due to] propellants that check recoil and muzzle flip in shorter barrels.” Fifteen cartridges from .22 WMR to .410 bore make up this line, in contrast with six common LE options in Critical Duty.

Unlike most of its ammunition sub-brands, Hornady Black, developed for AR-pattern and other modern sporting rifles, is not bullet-specific; instead, it might be best described as platform-specific. The select bullets—including FTX, MonoFlex, SST, V-Max, A-Max, InterLock, ELD Match, FMJ and more—are teamed with top-rate brass, primers and propellants specially geared to the rifle/chambering application, including short-barreled carbine loadings. Along with optimal ballistics, these loads are assembled to ensure fail-safe operation across the spectrum of direct-impingement, gas-piston, suppressed and subsonic platforms.

Max Loads

Two decades into the millennium, Hornady used Doppler radar to more fully measure bullets’ downrange flight characteristics as company engineers sought a profile that wouldn’t compromise priorities like minimal drag, over-the-course stability and, in hunting bullets, ready expansion at all ranges. The resulting Extreme Low Drag (ELD) series first appeared as ELD-X (eXpanding), followed by the ELD Match and then extended this year with ELD-VT (Varmint/Target). All of them rely on the proprietary Heat Shield Tip, the fix to Doppler-enabled discoveries that common plastic tips subjected to heat caused by air friction could melt and deform, thus degrading flight efficiency and accuracy. “Molded as precisely and consistently as previous polymer tips, the Heat Shield Tip boasts melting points hundreds of degrees greater than previous tips,” American Rifleman reported.

In addition to component bullets for handloading, marketing vehicles included groundbreaking Precision Hunter (PH) ammunition bearing the ELD-X, plus the addition of ELD Match bullets to the company’s medal-winning Match sub-brand. The PH family now numbers 25 cartridge alternatives, Match buyers have 14 ELD-M options and brand-new V-Match ammunition enters the market offering five loads. A handful of the latest Hornady chamberings, all designed from the headstamp up to maximize ELD technology, include the Precision Rifle Cartridges, comprised of 6.5 mm PRC (2016), 7 mm PRC (2022) and .300 PRC (2018). Much effort was made to craft cartridge case and chamber dimensions that match the efficiency of the new bullets. While successful in many applications, ELDs can fall short of their potential in older cartridges whose twist rates are too slow and necks/throats too short to make best use of such lengthy bullets. Seating depths that rob powder capacity (ergo velocity) can also hinder case-to-rifling bullet transfer, according to Hornady. The engineers told us that ideally, the bullet’s boattail/bearing surface junction should align with the case shoulder/neck junction. They call it “getting the bullet out of the case.” The PRCs do just that, as well as tighten up the chamber free bore tolerance to prevent bullet yaw. Also, headspacing PRC cases on their 30-degree shoulders rather than a rear belt facilitates precise chamber-to-bore alignment. All of these factors contribute to intrinsic accuracy. Their G1 BCs—6.5 mm PRC, 0.697; 7 mm PRC, 0.796; .300 PRC, 0.777—are among the best in class, and their rifling twist rates, typically 1:8", slot into the new generation typified by the Creedmoor.

And the hits keep coming. In 2024, yet another cartridge line has taken shape, as the new .22 ARC joins the earlier 6 mm ARC. Dubbed Advanced Rifle Cartridges, the pair adopts the mega-BC template by loading ELD-VT, ELD Match and/or ELD-X projectiles. Additionally, the cartridge case and chamber carry over improvements developed for the PRCs. Generating moderate chamber pressures despite muzzle velocities ranging from 2,800 to 3,000-plus f.p.s., both cartridges are groomed for black rifles as well as bolt-actions. The smallbore ARC promises to be a demon at controlling varmints and winning tournaments. Meanwhile, the 6 mm is a multitasker fully capable in competition and for dropping predators and deer-size game—but has another job, too. The cartridge actually evolved in response to a call from U.S. SOCOM seeking a “lightweight caliber capable of delivering a 50 percent hit ratio on man-size engagements at 2,000 yards.” In June 2020, the DoD called again, this time to enlist the 6 mm ARC in service to its country.

Amid its 20-year-long-range development blitz, Hornady’s new-idea train continued to bring other ingenious solutions that fit the many ways we want to shoot and hunt, including the DGS full-jacketed solids and DGX Bonded (expanding) Dangerous Game loads and the economical American Whitetail series. American Gunner, meanwhile, caters to tournament shooters and personal protectors, while the Vintage Match line helps history-minded competitors replicate the interior ballistics of original-duty ammunition in their classic rifles.

One of Hornady’s bolder moves has been Hornady Security, which started with the 2015 acquisition of SnapSafe, a firm best known for modular safes that can meet myriad gun-storage needs—with the line today also including a variety of products from racks and dehumidifiers to vault doors and TSA padlocks.

Hits Downrange

As important as Hornady is in today’s shooting world (see above), its story shines for reasons beyond bullets and ammunition. The company’s prosperity ripples across its community, something comically obvious every June 15, which is annual bonus day for employees. Along with good wages and benefits that still include a retirement plan, workers get extra in keeping with business fortunes, and each payment includes $100 cash in $2 bills. The company and the family generously give to numerous local charities, notably the United Way and youth groups including high school shooting teams. A series of Hornady-hosted shooting tournaments sponsors a local homeless shelter, and the company recently assumed management of the area’s state-of-the-art Heartland Public Shooting Park. Visitors come to town to salute the good works and economic windfall, as was the case in 2018 when U.S. Sen. Deb Fischer and Gov. Pete Ricketts attended the grand opening of Hornady West on the old Cornhusker Army tract, where two giant buildings now house production, distribution and R&D activities. More state and local honors than we have the space to list here have been conferred on the company and its personnel, the latest being induction of the Hornady family into the Nebraska Business Hall of Fame.

The shooting community is also Hornady’s neighborhood. Steve Hornady served nearly 30 years on the NRA Board of Directors, and likewise devoted his time to similar governance posts with NSSF, SAAMI and numerous other firearm-industry, shooting and conservation groups. Mr. Hornady has amassed a pile of lifetime-achievement honors, notably an NRA Publications Golden Bullseye Pioneer Award in 2013.

Hornady’s future looks bright. At 43 years of leadership and counting, Steve Hornady may step aside at some point, but the handwriting is on the wall for in-family succession. And remember that 10-years-out-of-the-nest rule for family members? Don’t read this as a prediction, but we can report that that clock is ticking. Seventy-five years aren’t enough.