When Winchester debuted the Model 1873 rifle, its purpose was to provide a more stable platform capable of handling more powerful cartridges than the .44 Henry Flat. That cartridge, introduced in 1860 in the Henry rifle, featured a 216-gr., internally lubricated, lead bullet propelled by more than 25 grains of black powder at around 1,125 f.p.s. from a 24" barrel. Its biggest claim to fame was its 15-shot tubular magazine.

The Henry rifle had a brass frame and locked up via a toggle link. A toggle link is sometimes referred to as an over-center link because its lockup occurs just over center, much like your knee when it locks. Winchester realized—after making its Model 1866 rifle that was similar to the Henry—that a centerfire cartridge could provide an increase in velocity, but it would also require a receiver made of iron instead of brass. So, Winchester kept the improvements of the Model 1866 rifle, made the receiver from iron (then later steel), added a sliding-dust cover to the top of the receiver and chambered it in a new centerfire cartridge, the .44 Winchester.

The .44 Winchester, also known as the .44 Winchester Central Fire and later as the .44 Winchester Center Fire (W.C.F.), featured a 200-gr., flat-point lead bullet propelled by over 40 grains of black powder at 1,245 f.p.s. from a 24" barrel, although Winchester originally claimed 1,300 f.p.s. Almost immediately, the cartridge and rifle were a hit. The Henry was popular during the Civil War, and the Model 1866 was popular later on the frontier. Firepower is quite desirable in a fight against multiple adversaries. Having a stronger rifle with a more powerful cartridge, and maintaining the firepower advantage, was a big improvement in rifle design.

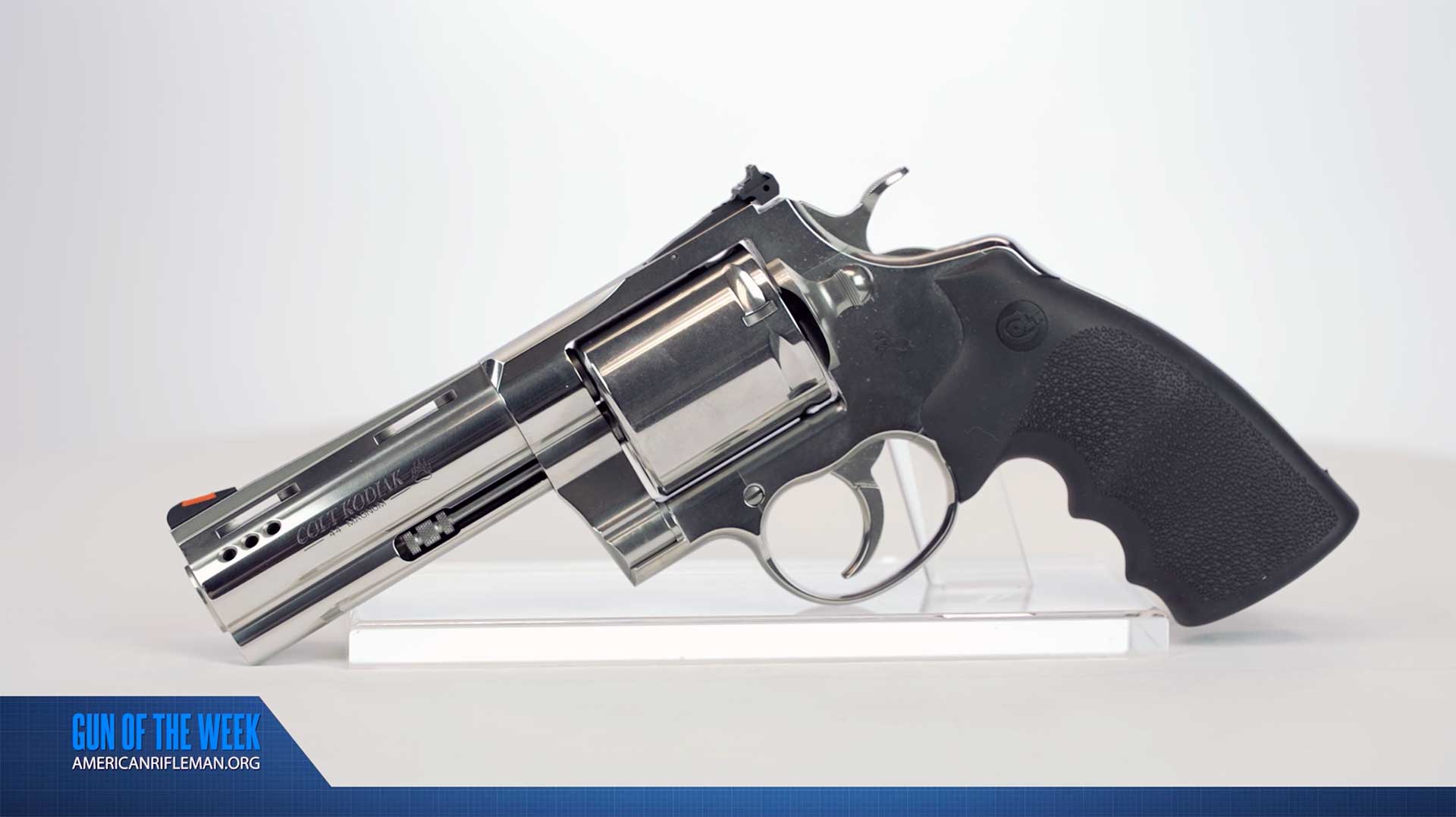

The centerfire cases could also be reloaded, and Winchester even sold a reloading kit. This was another big advantage on the frontier, where stores that sold guns and ammunition were somewhat few and far between. Colt brought out its equally iconic Single Action Army in the same year, initially chambered in .45 Colt. It was necked down to .44, the rim and case length were lengthened and the revolvers were rechamsbered to .44 W.C.F., calling it the Colt Frontier Six-Shooter.

Now frontiersmen had the benefit of having a rifle and pistol chambered for the same cartridge. Smith & Wesson also got in on the .44 popularity, chambering its Model 3 revolver for it in 1877. Interestingly, original Winchester .44 W.C.F. ammunition had no headstamp. It would not be until 1886 when a headstamp was applied, “W.R.A. CO. .44 W.C.F.” The Union Metallic Cartridge company (U.M.C.) soon began loading the .44 W.C.F., but because of its desire to not promote a competitor, labeled it the .44 C.F. and later as .44-40.

Still later, Winchester poached the .44-40 designation and added W.C.F. to the stamp on its rifles. Rifle development continued, and as with the Browning-designed Winchester Model 92, Marlin had its Models 1888 and ’89 rifles chambered in the cartridge. The main difference between the two rifles was that the Model 1889 is side-ejecting. As double-action revolvers came onto the market, several companies including Colt with its Model 1878 and later New Service revolvers, Smith & Wesson, Remington and Merwin, Hulbert & Co. produced examples in .44-40 W.C.F.

When smokeless powder took over from black powder, such loads in .44-40 W.C.F. were offered. The Winchester loading, introduced in 1893, had the same 200-gr. bullet in front of 17 grains of DuPont No.2 smokeless powder. This powder was considered a “bulk powder” that could be loaded bulk to bulk (or to the same volume) as black powder at an advertised velocity of 1,300 f.p.s., and identified by the “W” stamped on the primer cup. U.M.C. loaded its 217-gr. bullet with the same charge of powder for an advertised 1,245 f.p.s.

By the mid-1890s, jacketed or “metal patched” bullets were being offered to stem the leading of barrels due to the higher velocities smokeless powders produced. In 1903, Winchester debuted a “Winchester High Velocity” load for its cartridge, headstamped “.44 W.C.F. W.H.V. ’M92” for the Model 1892 rifle. Ballistics were touted as 1,500 f.p.s. using the same 200-gr. metal-patched bullet, and seven years later the velocity was bumped up to 1,570 f.p.s. Winchester packaging stated this load was not suited for Model 1873 rifles or revolvers, but we all know how some people are.

Several of these loads found their way into weaker guns with varying, often unpleasant, results. U.M.C. loaded a high velocity cartridge as well, headstamped “U.M.C. .44-40 H.V.” These high velocity loadings were curtailed after World War II, as many cartridges began getting standardized at lower velocities to keep shooters’ fingers and eyes attached. My experience with the .44-40 W.C.F. has demonstrated that it’s a good cartridge for shots out to 100 yards, perhaps a bit further in a hot load from a rifle.

When I first got my Uberti copy of an 1873 Winchester, I played with a few smokeless loads just to see what it would do. The buck-horn sights aren’t very helpful for 60-plus-year-old eyes, especially past 75 yards. Still, on a man-sized target a good shooter should be able to keep his shots somewhere on the target out to 150 yards. The only experience I have hunting with the cartridge is for rabbits and ground squirrels, and they were all taken with black powder hand loads.

Because modern cases are solid head, as opposed to the old balloon-head cases, it’s capacity is reduced. I can only fit about 38 grains of Goex FFFg in my Starline cases. That load clocks in at 1,100 f.p.s. from the Uberti Model 73, and 776 f.p.s. from my 4.75" barreled Colt Single Action Army revolvers. With the 212-gr. (as cast from my molds) flat-point lead bullet, these generate 570 and 279 ft.-lbs. of energy respectively.

I would not be comfortable using this on deer, however it is said that the .44-40 W.C.F. has killed as many or more deer than the .30-30 cartridge has. Either way, that is a lot of deer. Today, you can still get a Model 1873 from Winchester chambered in .44-40 W.C.F. made by Miroku, and it's a fine rifle. Ammunition—if you can find it—is relegated to cowboy action loads featuring a 225-gr. flat-point lead bullet at roughly 750 f.p.s. from Winchester Ammunition. Numerous copies of both revolvers and rifles exist, most being made outside the U.S.

There is little doubt that the .44-40 W.C.F. is the cartridge that won the west. More Model 1873 rifles were chambered for it than all the other cartridges combined. Yes, there are more modern cartridges and loads that equal or surpass this nearly 150-year-old cartridge, but its still a viable option to this today.

![Auto[47]](/media/121jogez/auto-47.jpg?anchor=center&mode=crop&width=770&height=430&rnd=134090788010670000&quality=60)