The world didn’t end, and there was no immediate evidence of porcine aviation. But my morning’s coffee spewed on the pages of Jan. 26, 2006, Washington Post was enough to demonstrate that the world was somehow out of balance. Appearing in that liberal, anti-gun journalistic bastion was one of the finest articles on firearms I’d ever read. When the U.S. Repeating Arms Co. factory closed, a film critic for the Washington Post wrote a heartfelt piece, “Out With A Bang,” for the paper about the legacy of Winchester-in particular the Model 94. In my opinion, it was the finest tribute written on that legendary firearm.

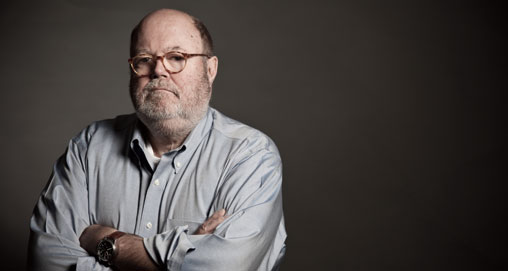

It should have come as no surprise, though, as that writer was Stephen Hunter-a veteran journalist and film critic with The Baltimore Sun and then The Washington Post who earned a Distinguished Writing Award from the American Society of Newspaper Editors in 1998 and a Pulitzer Prize For Criticism in 2003. Hunter is also a New York Times bestselling novelist and one of the finest writers in America. Best of all for shooters his novels are well-known for presenting firearms in a technically correct fashion and giving them prominence in his plotlines. He has written 14 novels and introduced the character of Bob Lee Swagger in “Point of Impact” (1993). That novel was adapted by Hollywood into the feature film “Shooter,” starring Mark Wahlberg, in 2007. Hunter is also the author of three non-fiction works, and, in my opinion, “American Gunfight: The Plot To Kill Harry Truman And The Shoot-Out That Stopped It” has one of the finest descriptions of a an actual gunfight ever written.

Hunter, retired from the Post, recently made a trip to NRA Headquarters. It turns out he really is a shooter’s shooter and, despite his protestations, is a fine pistol shot. His newest novel, “I, Sniper”, has just been released by Simon & Schuster, and don’t be surprised to see his byline appear in American Rifleman in the near future. I was fortunate enough to sit down with him to talk about guns, books, movies, politics and the media.

Keefe: You’ve had a lot of different careers as a writer. But one thing that has come through, especially in your novels, is your passion for firearms. How did you get involved in shooting?

Hunter: You know, there was never any getting involved in it. I was always in it. I can’t specify the first moment I saw and loved a gun, but it’s got to be sometime in the early 1950s. I remember a kid next door had a .22, which I thought was neat. I remember visiting an uncle’s farm in Missouri. They had guns, and I always wanted to shoot.

Television and the movies in those days were flooded with images of guys with guns used heroically and nobly and honorably, and I absorbed all that. It was clear to me from a very early age that the guns were very vivid to my imagination, and that I had a very powerful response to them. I make my living from my imagination. I need stimulation, and firearms have been really a reliable stimulation for close to 60 years now. I mean it’s been a very happy life, and I’ve benefited immeasurably from my passion for guns.

Keefe: NRA Secretary Maj. “Jim” Land served in Vietnam and was one of the architects of the modern Marine Corps sniper program. After he read “Point Of Impact,” he told me he didn’t necessarily want to read it, but he wanted to find an “I got you” in it. After he read the book, he told me that you didn’t get anything wrong.

Hunter: He told me that, too, and it makes me very proud. One of the early motivations was that, of course, there’s also a lot of junk in popular culture about guns. We’ve all seen movies where a six-shooter fires 75 times, and the guy kills a sniper from 200 yards with a hipshot from a Colt Detective Special, and that sort of thing. One of the things from the very beginning was I wanted to portray the guns accurately. I wanted to understand what they did and what they didn’t do. I wanted to talk about how they were used, what the dynamics of firearms encounters were as opposed to what the Hollywood vision of them was. I figured Hemingway once said something like, “The way you start every morning is you try and think of ‘One True’ thing.” Well, I didn’t know much about anything except guns. So, I thought, if I can get one true thing about a gun in, maybe that would take me somewhere interesting. And so all the books sort of turn on the fulcrum of a particular gun being used or not being used, and I’ve always gone to great pains-maybe too great a pain-to make sure that I got the details right. And I’m quite proud of that. I got some things wrong, but I haven’t made too many terrible mistakes.

Keefe: You actually use firearms as plot devices. They almost take on the role of characters in your books.

Hunter: Yes, I do. And that’s why the books almost always begin with guns. I try to imbue the characters with the virtues of the gun. You know, like Bob Lee Swagger, who is sort of a human M40A1 sniper rifle. He’s accurate, he doesn’t miss, he’s rugged, he doesn’t go out of zero, he understands what to do, he holds together in tense, extreme moments. For the simplicity of his appearance, he is enormously sophisticated underneath. So in that sense he and the rifle have a commonality. In other ways, you can use guns to characterize bad guys.

In the new book “I, Sniper,” the bad guy has the very latest generation of computer-driven, ballistics calculator scope. And Bob just has a mil-dot scope. So there’s something of the virtue of Bob, and the willingness of the bad guy to “cheat.” I would like to see all our soldiers in the field with computer-driven ballistic calculator scopes, but in the framework of the book it’s very clear that one scope is good and honorable, and the other scope is a reflection of the bad guy’s willingness and ruthlessness to use technology to compensate for lack of talent. Which is a bad mistake when you’re dealing with Bob Lee Swagger, as he finds out.

Keefe: In “Point Of Impact,” you introduce Bob Lee Swagger, and Hollywood’s adaptation of the book became “Shooter.” Considering your background, considering that for so many years you were a film critic, how was it moving to the inside of Hollywood as they adapted your book into “Shooter?”

Hunter: It was basically rather pleasant. They respected the book. They understood, at some level, that principle, and I just laid out that I was trying to be accurate with the guns. The whole cast and crew went to a shooting school. One of the things that was good about that movie (and believe me there are bad things about it) is the gun handling. The gun handling-the way they move with the guns and the way they shoot the guns-is very professional, as it should be because we were portraying high-level professionals. The action sequences with the guns, I think, are all very high quality.

And that, in a funny way, was what I had hoped to get out of it. And one of the reasons that the DVD has been so successful, it’s become such a cult item, is because gun people watch it, and they instinctively know that they’re getting something that’s genuine, and I’m hoping that’s why they read the books because they understand that it’s done with respect and a good deal of care and research to portray the guns as accurately as possible.

Keefe: I think “Hot Springs” was probably the best of that series, but in terms of entertainment value for a guy who shoots, “Pale Horse Coming” is the book.

Hunter: See, you’re getting it. And people in gun culture get it. One of my little secrets is that a lot of the characters, a lot of the plot gambits and a lot of the gunfights themselves are drawn from what might be called classical gun culture. And outsiders don’t recognize that. In that book, there are six old gunmen coming into the book. And if you know your gun culture history, you will know who they are.

I still get e-mails asking which one was Charles Askins, which one was Elmer Keith, and that sort of thing. So I had fun with that. The new book, “I, Sniper,” is also based on a lot of characters out of politics and, particularly, out of gun culture. If you know your gun culture, you will understand who the antecedents are, and I hope that provides an extra level of pleasure for people inside.

Keefe: In “I, Sniper,” you set what really is the classic gun culture against technology. What was your inspiration?

Hunter: Well, I’ve always been attracted to snipers. I will say this was a peculiar book because Simon & Schuster wasn’t interested at all. They wanted me to go back into a classic Bob Swagger book. From my e-mails and from comments on Amazon, and on all the Web sites, I realized that people were really hungry for me to do a classic sniper book. So I took up an idea that I had 15 years ago. I thought it was a very good premise, and could never figure out quite how to end it. And every ending I came up with was lousy. So I took that premise, and finally 15 years later I figured out where it could go and what would be interesting about it.

Suddenly at that point, it took off, it became very vivid for me and, of course, you’re always looking for a dichotomy. And 15 years ago, there never would’ve been the issue of mil-dot versus computer chip. It just didn’t exist. But suddenly I saw that as a dichotomy, as a way of distinguishing the two sides and contrasting the wisdom of a veteran, and the savvy and experience against the high-tech gizmo of the bad guy. I saw that could make a really interesting sort of way to set the book up. And also, it expressed my fear and loathing of the complexity of long-distance shooting.

Keefe:Working at The Baltimore Sun and at The Washington Post, you were in an environment that was obviously very much in favor of just about any kind of gun-control. Where do you come down?

Hunter: I’ve always loved guns, and I always want access to guns. Guns have provided me with a life of the imagination, they’ve provided me with a financial life, and they’ve provided me with a life of recreation. They’ve also provided me with a political life. When I began, I was a very conformist little twerp in my twenties. I probably went through a period of about five years where I was the typical snarky anti-gun liberal. This was back in the 1960s. Even then I was aware that at some level I was lying; I was not being true to my self.

I was trying to fit into a culture. I will say that everybody was always good to me in newsroom culture. They were wonderful to me on the Sun; they were wonderful to me on the Post. I have no personal animus toward any newspaper person or any colleague or anyone who was snarky to me because, as I grew older, I became more honest about what I was. It became known that I was an NRA member and, to many of them, that is totally inconceivable.

I always saw myself as an ambassador. I always wanted them to say: “Hey, here’s a guy who knows the difference between a .30-’06 Sprg. and a .308 Win., and yet he’s OK. He’s a decent guy, he works like a dog, he contributes to the paper, he’s funny, he’s ironic. He shares our sense of humor; he shares our sense of this or that.” I never wanted to be an unpleasant proselytizer. I said to them, “Look, if you have any questions on gun issues or technologies, I’d be very happy to answer them no matter what.” And as we all know, with the exception of the pieces that I write, the definition of a gun story in a newspaper is a piece of writing with a big stupid technical mistake in it. And that continues to this day.

One of the themes in “I, Sniper” is how an extremely sophisticated news organization can make a really stupid gun error and have no idea that they’re doing it. And the larger question that I’m asking, that I want people to take away from it is: How can you be so certain of your politics if you have such an infirm grasp of the reality of the instrument? You know, maybe if your grasp of the reality of the instrument is ludicrously incorrect, maybe your grasp of the politics of the instrument is ludicrously incorrect, and you want to re-examine both issues. Don’t mix a Remington up with a Winchester, and don’t tell me that banning .223 is going to save lives.

But so much of it is so stupid, and so driven by ignorance. One of the things I wanted them to see was that gun people weren’t a tribe of troglodytes and Neanderthals but are in fact human beings just like themselves. And that the gun world (and even NRA) wasn’t a monolithic battalion of marching robots. But there were disputes within as well as outside of gun culture: There are politics and cliques, there were personalities. And that gun culture wasn’t different than the world, but that gun culture was the world. There are really good people, and there are some people who make everybody a little nervous, but that’s true, that’s the bell curve of human reality. And if we could only see that, instead of thinking stereotypically, then our tolerance, our forgiveness, our willingness to accommodate other points of view and our ability to all get along together without anyone imposing anything on anybody, all that becomes possible.

So that was one of my missions as a journalist for 38-odd years. Whether I accomplished that or not, I don’t know, but that was what was really important to me.