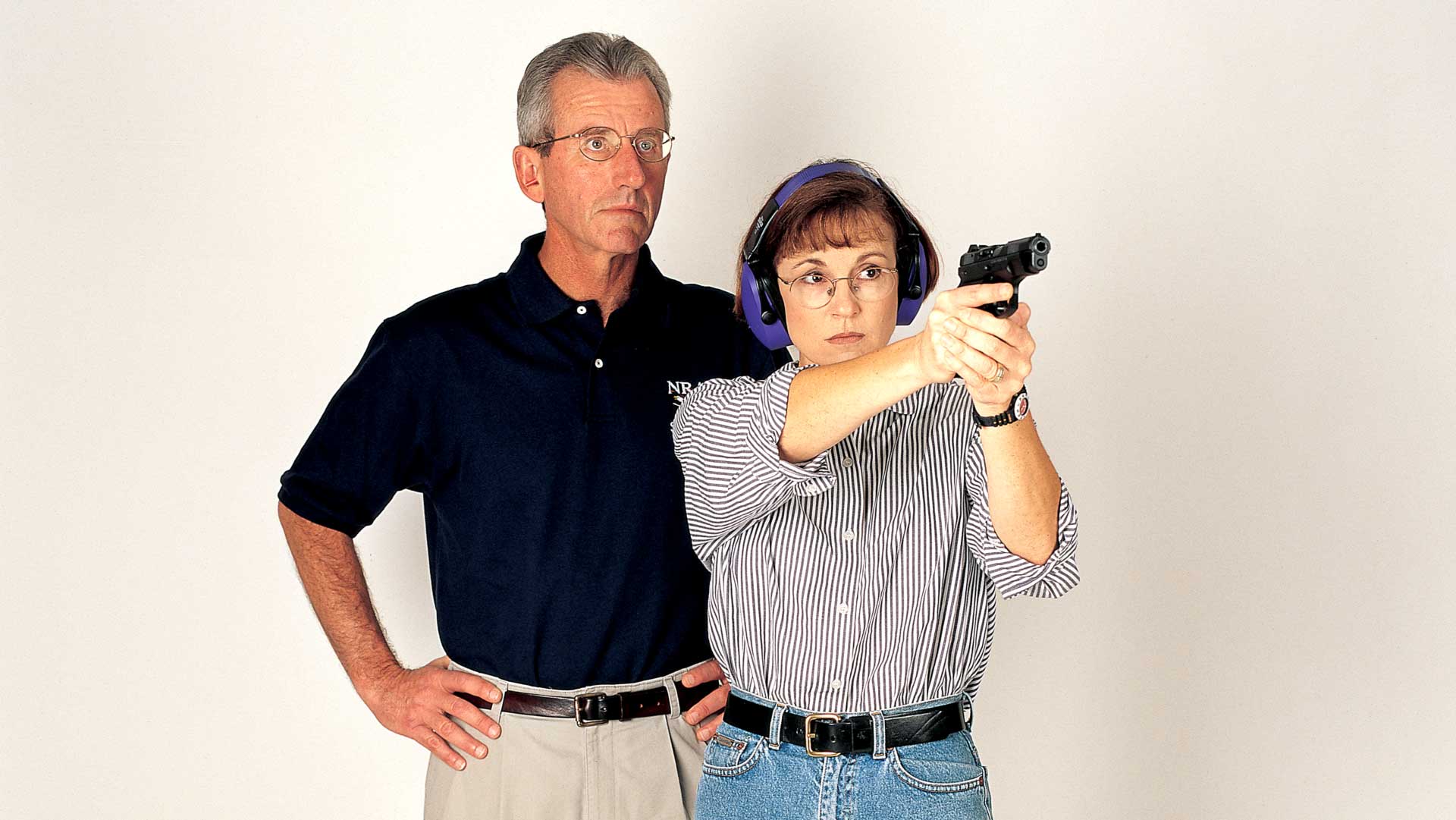

“Always point the muzzle in a safe direction.” That statement is one of NRA’s three rules for safe gun handling. For the purpose of properly illustrating the major handgun stances, we’ve bent that rule in the images that appear in this story. The guns used here were all unloaded, and no ammunition was present at the author’s photo shoot. Also, the models are not wearing eye and ear protection to better demonstrate head positions in relation to the sights. Always wear eye and ear protection when shooting: You only get one set of eyes and ears. —The Eds.

In the evolution of firearms, the handgun became a close-up and personal firearm that no one considered useful at any but the shorter ranges. It took centuries for that notion to disappear, but eventually the IHMSA shooters and handgun hunters proved that accuracy at considerable range was possible. In the distant past, handguns came to be useful, not only for their size, but also for their one-hand nature. In military use, the shooter who needed a one-hand gun the most was the cavalryman. Using one hand to manage the horse’s reins, the cavalry soldier could successfully manage the handgun at short ranges then use his saber when he got within striking distance.

As time passed and handguns evolved into repeating revolvers that were reliable, horse soldiers and officers began to use them more and more, eventually relegating their swords and sabers to ceremonial use. In the American Civil War, the revolver became a truly decisive arm, and mounted troopers wearing both the Blue and the Gray often carried them in pairs—even multiple pairs. Revolvers of that era were almost always used one at a time, not one in each hand. The trend became almost pervasive, because the handgun was capable of being used in one hand and was most commonly used that way by mounted men who needed one hand for the reins.

The implications of this were far-reaching. From the time of the American Civil War to the post-World War II era, you seldom saw an illustration of a shooter firing either pistol or revolver in anything but the one-handed stance of the duelist or classic Bullseye shooter. With a few rare exceptions, nobody fired a handgun any other way, because no instructor or school taught firing any other way. The major forms of handgun competition required shooting with one hand. For a military or civilian organization involved in teaching handgun shooting, it was relatively easy to conduct Bullseye training on known-distance ranges, so it became the accepted way to do it. As a Marine in the ’50s and ’60s, I was taught to shoot one-handed and regularly qualified in this system. I also fired both service and NRA matches with the pistol firmly clasped in my right hand, extended at arm’s length toward the target. As a deputy sheriff in the ’70s and ’80s, I was taught to shoot that way and was allowed to qualify with that method.

In the earliest days of formal one-handed shooting, the influence of the duelists and Olympic shooters was strong. Usually, this resulted in a Bullseye stance where the right-handed shooter literally “faced north and shot east” with the pistol extended straight out from the shoulder and the torso facing a full 90 degrees away from direction of fire. I can’t imagine doing this for a full 2700 aggregate, but it was once the standard. In time, however, we learned to turn into the direction of fire a little more (face northeast and shoot east), which is considerably more relaxed and comfortable. Indeed, the non-shooting hand usually goes into the off-side front pocket. The Blankenships and Zins of modern times have done remarkable things in this position. An accomplished pistol marksman who competes—even today—must master this stance.

But even in the days before World War II, there were individuals at work developing techniques of shooting that were more relevant to the use of the handgun as a defensive firearm. The most significant of those came from the Municipal Police of Shanghai, China. To the best of my knowledge and belief, Fairbairn and Sykes were the first to study defensive shooting scientifically and from the standpoint of considerable personal experience. As police officials in a violence-ridden city, they developed a shooting style built around a deep crouched position, which they felt was far more realistic than the one-handed, upright bullseye position. Many factors went into the use of that technique, but it found its way into the pages of this magazine in the ’20s and ’30s. The Fairbairn system eventually made its way to the United Kingdom at the outset of World War II. The late Col. Rex Applegate brought it to Office of Strategic Services (OSS) training and again to the pages of American Rifleman during World War II. The stance caught the eye of FBI officials who began to integrate it into their agent training in the post-war era. Properly taught on realistic ranges, the crouched stance is an effective, defensive method of shooting. It involves firing without use of the conventional sights, but rather by pointing the gun quickly at a close target. Point shooting styles vary quite a lot from one instructor to the next, but almost always involve gripping the gun with one hand. The other hand is usually out to the side to assist in maintaining balance.

Defensive shooting as a martial art began to attract a great deal of interest in the Southern California area during the 1950s. Much of it was civilian-developed, but it resulted in the phenomenal growth of the Southwest Combat Pistol League, which eventually blossomed into the Int’l Practical Shooting Confederation. Colonel Jeff Cooper was responsible for the initial popularity and growth of this movement, which is undeniably the strongest positive trend in the history of handgun shooting.

In the beginning, Cooper’s idea was to promote practical shooting competitions that were completely unrestricted as to positions and other details. And when there were few restrictions on how you were to shoot the match, it quickly became obvious that shooting with one hand, when there was no sound reason for doing so, just didn’t make sense. A local deputy sheriff began to use both hands in a powerful stance that bears his name to this day—the Weaver. Some authorities have noted the use of something very like the Weaver stance in earlier times. There’s an illustration in J.H. FitzGerald’s 1930 book Shooting, where the author demonstrates a stance much like the Weaver. It is not quite the same, and ol’ Fitz doesn’t advocate the use of the position as broadly as did Jack Weaver and Jeff Cooper.

The Weaver stance has become very popular and is a cornerstone of modern defensive pistolcraft. Today, it is widely taught in both civilian and military schools. A right-handed Weaver shooter faces the target with feet about shoulder width apart, and the left foot slightly forward of the right, which angles the pectoral girdle slightly away from the target. As he presents the pistol with the right hand, he simultaneously raises his left hand and grasps the right, wrapping the fingers around the right hand as it holds the butt. Positive pressure forward with the right hand mated to pressure rearward with the left stabilizes the gun in place. It is at eye level and the sights are in use. The right arm is straight or nearly so, while the left arm is bent rather sharply at the elbow. Over the years we have been going at it

Weaver-style, a number of sensible variations on this position have evolved. None of them vary far from this powerful stance, which is remarkably like that of a boxer, judo player or skeet shooter. The Weaver stance combines the twin virtues of strength—for recoil recovery and accuracy—and flexibility to engage multiple targets and changing positions.

Other instructors approach defensive shooting with a two-handed hold, but from another stance. Much of the use of the Isosceles position came from shooting sports (IPSC, PPC, and NRA Action Pistol), but it is beginning to find favor with a number of police and defensive instructors. In the Isosceles, the shooter squares to the target with the gun in a hard two-handed grip. He pushes the gun straight out from the shoulders with both elbows locked, thereby forming a triangle that gives the stance its name. Unless the handgunner leans aggressively into the position, he may be unsteady in the fore and aft vector. Some trainers now teach dropping the strong side foot back slightly, while keeping the shoulders square to the target. This is more stable, but it is also rather rigid and inflexible.

A local deputy sheriff began to use both hands in a powerful stance that bears his name today—the Weaver. It has since become a cornerstone of modern defensive pistolcraft.

That’s fast and furious through the stances of defensive handgun shooting. There are quite a few, and they exist for many different reasons. Before leaving the topic, however, I would like to point out a fact that just never seems to make it into discussions of handgun shooting technique. We have all seen pictures of it or have been instructed by some crusty rangemaster type. Conventional wisdom causes the pictures to be taken or the rangemaster to solemnly tell us that the pistol must be held so the axis of the bore and sights is an extension of the forearm, clear back to the shoulder and to your aiming eye or eyes.

That’s physically impossible. In any of the positions we have discussed, the line of sight actually runs at least slightly inboard of the line of the arm. You come closest to getting that mythical straight line from the eye down the arm to the front sight when you are shooting in the old duelist or Bullseye position. None of the modern stances allow you to do that, and shooting in a position like the Isosceles places you a long way from the theoretically ideal line. The shooting wrist invariably bends just a little. As a practical matter, it seems to make very little difference; we are still able to control recoil and align our sights with accuracy. The accompanying photos, taken from above and forward of the shooter, illustrate the problem well. If you were to tape a long dowel along the sights of a revolver, running it back to the shooter’s eye, the line of sight—represented by the dowel—wouldn’t run along the arm, now would it?

This feature article, "Handgun Shooting Stances," appeared originally in the November 2005 issue of American Rifleman. To subscribe to the magazine, visit the NRA membership page and select American Rifleman as your member magazine.