Countless conversations take place around safari campfires each season, analyzing the rifles and chamberings that are used for hunting Africa’s dangerous animals. Opinions about the guns and ammunition that are best-suited for the purpose are as varied as the individuals who espouse them, which often fuels differences of opinion, if not heated debates.

One indisputable fact, though, which is unanimously agreed upon, is that regardless of the rifle/cartridge combo, there must be total familiarity with it. The rifle must fit the shooter as if it were an extension of his or her arm, and complete reliability is essential for providing the confidence needed when lives are on the line.

Here are profiles of three of Africa’s most respected and recognized professional hunters, who sadly are no longer with us. The respect they earned and the success they enjoyed only came from years of experience and being very good at what they did. All of them carried rifles in which they had total and complete confidence, and they used those same rifles for most or all of their careers. All three hunters approached their choice of rifle from different angles and for different reasons, and their guns could not be more different—but they all provided unfailing service, ensuring that the PH’s clients and native staff all returned safely from the hunt.

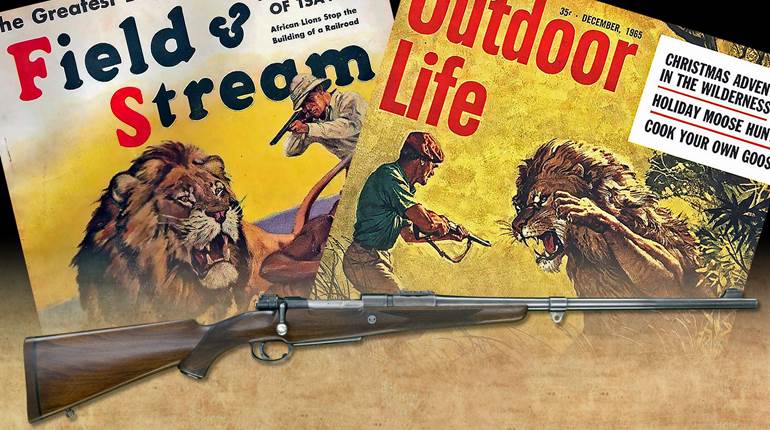

The Rigby .416 Mauser 98 is unique in that it features a standard-length commercial Mauser 98 action rather than the magnum-length action typically used to handle the .416 Rigby cartridge.

Selby's .416 Rigby

Harry Selby began his professional hunting career with a best-grade Rigby .470 Nitro Express double rifle in mint condition that, at the time, cost around 100 pounds sterling (USD $270). However, while on safari in northern Tanganyika in 1949, Selby’s rifle was damaged beyond repair when Donald Ker accidentally drove over the barrels.

Selby was devastated, and to make matters worse, he had a three-month safari starting immediately after that one finished. Upon returning to Nairobi, he began looking for a replacement, fully expecting to buy another double rifle.

But time was short, and there were no heavy double rifles available. The only heavy rifle he could find for sale was a Rigby magazine rifle chambered for .416 Rigby in new condition for under 100 pounds sterling. With no other options, Selby bought it, expecting that it would provide a stopgap until he could find another double rifle to his liking. Little did he know that the decision to buy the Rigby was one of the most important decisions he would make in his hunting career.

Once he was on safari, Selby very soon realized that, for him, the .416 rifle/cartridge combination was far superior to any double he’d ever fired. And so began a lifelong love affair between Selby, the .416 chambering and the Rigby rifle. One interesting fact about Harry’s Rigby is that it was made on a standard commercial-grade Mauser 98 action and not a magnum action on which most of the .416s were built.

“The inherent accuracy of a bolt-action was apparent from the very first shot,” he reflected. “The phenomenal penetration was to make itself evident as time went by. I also appreciated the four-round magazine and, on several occasions, was glad that those four rounds were ready and waiting.”

Suffice it to say that, after just two safaris, Selby would not have gone back to a double under any circumstances. In the .416 Rigby he had found his perfect “professional hunter’s rifle”—a beautifully balanced, fast-handling rifle pushing a 400-grain bullet fast enough to enable it to reach out up to 300 yards, if necessary, when trying to bring down a wounded animal and yet perform with devastating effect on large dangerous game at close range. Selby was impressed!

In 1952, fate brought Selby and Robert Ruark together for an historic safari in Tanganyika. It was an African hunt that would be immortalized in Ruark’s entertaining account of six weeks in the wilds of Africa with Selby, entitled Horn Of The Hunter—a book that is still in print today. It would be the first of many safaris that Selby and Ruark did together over the next 10 years. The respect and admiration Ruark felt for Selby’s .416 Rigby, not to mention its owner’s impressive marksmanship with the gun, was not lost on a vast readership covering nearly 70 years. It resulted in the Rigby rifle achieving legendary status among generations of hunters from all over the world. Today, the .416 is in the hands of a longtime safari client and very good friend who preserves the rifle in a place of honor.

Kingsley-Heath,s .470 Nitro Express

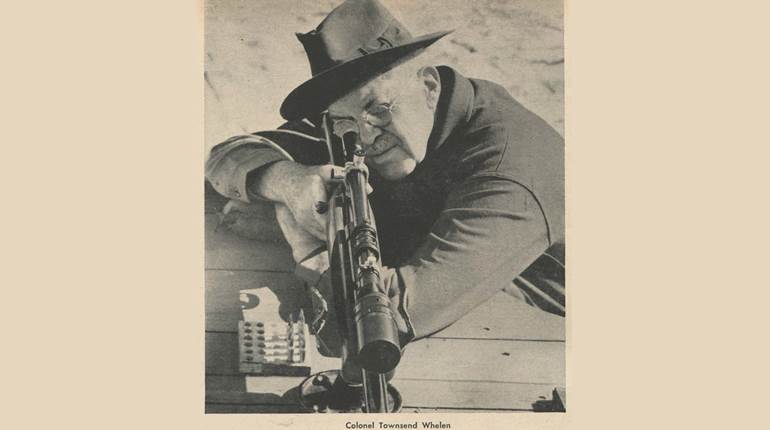

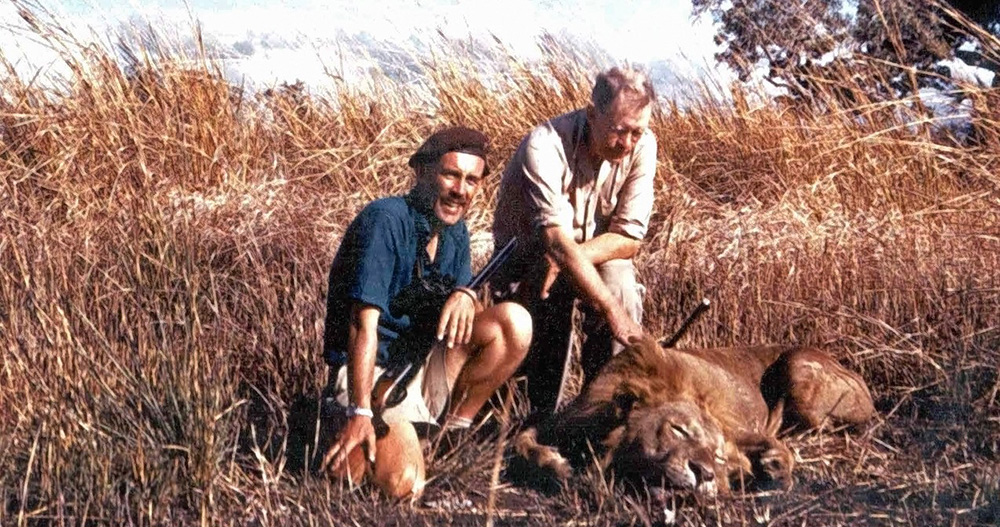

The late John Kingsley-Heath (JK-H) accompanied Jack O’Connor, Outdoor Life magazine’s longtime shooting editor, on many of his African safaris going back to 1959. O’Connor considered JK-H a good friend and referred to him frequently enough in his hunting articles and gun columns as “the famous white hunter and crack shot” for Kingsley-Heath to become a familiar name to readers. JK-H himself even wrote a couple of articles for the magazine. In August 1961, he was severely mauled by a wounded lion while hunting with safari clients in central Tanganyika. Even though armed with his .470 NE-chambered Westley Richards double rifle, unfortunate circumstances made him unable to stop the lion as it attacked. JK-H recalled the horrifying experience with perfect clarity in “A Lion Mangled Me,” which appeared in the March 1963 issue of Outdoor Life.

In January 1965, JK-H was drawn into another lion incident that ended up being illustrated for a cover of Outdoor Life that year. He and a client happened upon a grisly scene in which a man-eater had killed a native only a few hours earlier. They followed the lion’s tracks, eventually confronting the man-eater that immediately charged. JK-H knocked the man-eater down with two shots from his .470, ending the reign of terror the big cat had caused with the demise of 26 natives. JK-H’s account of that tragic incident entitled “The Man-Eater of Darajani” appears in the December 1965 issue of Outdoor Life.

Jack O’Connor, shown with his Tanzania lion, went on several safaris with John Kingsley-Heath—seen here with his .470 NE double rifle.

JK-H’s inherent interest and experience with big-game rifles and cartridges was extensive, and it made him the ideal companion on safari with respected gunwriters and firearm aficionados of the day such as Robert Chatfield-Taylor, Warren Page, Roy Weatherby, Elmer Keith, Charles Askins, John Taylor and, of course, Jack O’Connor, with all of whom he was able to compare notes and experiences.

There were few big-game rifles with which JK-H was not familiar, but the Westley Richards .470 NE double was the one in particular that he favored, and on which he often entrusted his life. He used it for backing-up clients on the big game, and he listed the advantages he felt it provided in his book Hunting The Dangerous Game Of Africa. The list included the double being a shorter and handier package, providing two certain shots, handling like a shotgun on moving targets, and enabling rapid and silent loading.

“My .470 Westley Richards ‘White Hunter’ Model cost 185 pounds sterling (roughly half my annual salary) in 1955,” JK-H wrote in his book. “It was a boxlock action with no engraving, except for the maker’s name, a simple stock, no cheek piece, one solitary mounted back sight with a good V and a strong, clearly white metal foresight. I must have fired upwards of 2,000 rounds from it.

“I owe my life to its reliability and its precise and simple engineering and manufacture. It has been my right hand at nearly every tight corner in which I have found myself when hunting big game as a professional hunter … . In short, it did me proud for 40 years. No other [rifle] that I owned gave me such confidence and results. God bless Westley Richards for that.”

A Westley Richards bolt gun chambered for the .425 Westley Richards cartridge, with its extended five-round magazine and 26" barrel, was another favorite heavy rifle on which JK-H relied. “The .425 Westley Richards,” he wrote, “was easy to work and very accurate. The ballistics for such a small cartridge were very impressive, producing no less than 5,300 ft.-lbs. of muzzle energy.” In his book, JK-H named several big-game cartridges for which he had great respect: “From my experience, I am convinced that the calibers .416, .425, .458, .470 and .577 have the best combination of ‘knockdown effect’ on the largest animals—elephant, rhino and hippo—and that a majority of hunters are able to handle. I would add that I am sure that there are other calibers that anyone of similar experience would add to this list, namely the .500 Jeffery.

“I can well remember the nights spent with Jack O’Connor ‘round the campfire, discussing this subject,” JK-H said. “Ideally, you need to kill the animal cleanly and efficiently without its knowing that it has passed on, but in doing so, you do not need to seriously impair the hunter from ever attempting to collect another trophy in the future as a result of firing too heavy a rifle.”

Johnson,s .375 H&H Magnam

As versatile and popular as the .375 H&H Mag. is, it has always been considered a marginal cartridge for the largest game. In Kenya, the game laws excluded the .375 from being used for the thick-skinned dangerous game, requiring a .400 caliber or larger in order to hunt buffalo, rhino and elephant. Although .375s have accounted for many buffalo and elephant throughout Africa’s hunting areas, it was not a chambering generally considered large enough for backing-up safari clients hunting dangerous game.

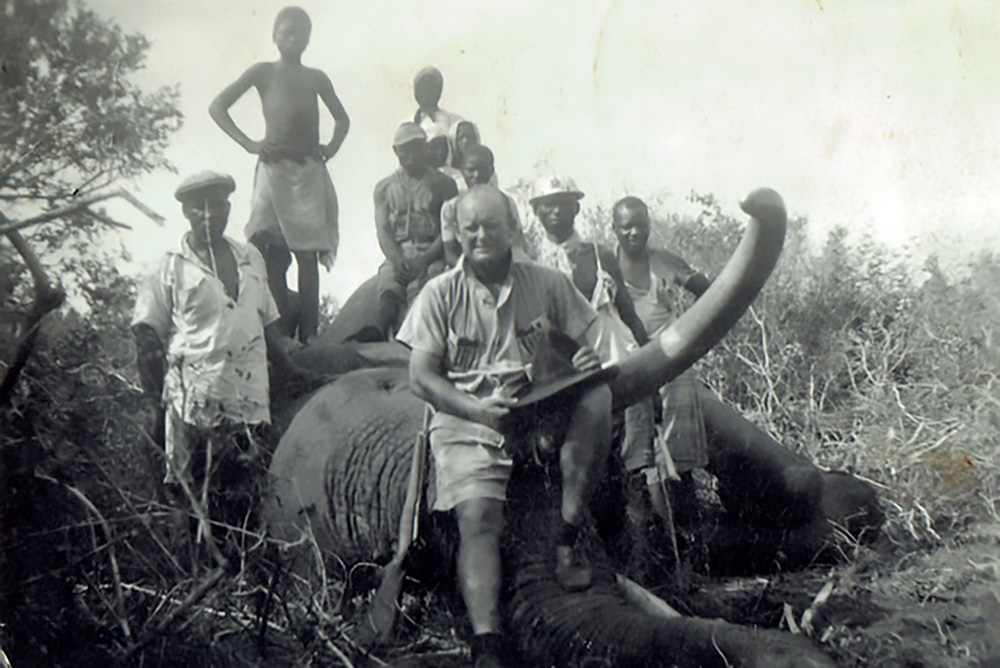

In spite of that consensus of opinion, it was Wally Johnson’s cartridge of choice for a period spanning more than 60 years. Wally, who hunted for a living, both for ivory and for meat, as well as guiding visiting hunters, never had a complaint about his choice of rifle or cartridge. During his safari-hunting career, he guided many notable clients, including Field & Stream’s Warren Page, Fred Huntington of RCBS, Peter Barrett of Fawcett Publications, famed archer Fred Bear, TV and radio personality Arthur Godfrey, gun aficionado and ballistician Jack Lott and novelist Robert Ruark. Many of his clients, including Ruark and Lott, hunted numerous times with Johnson, who was highly popular and often booked several years in advance.

Critical to the safety of Johnson’s clients was his rifle. He owned many, but the one that stood out was a Winchester Model 70 chambered for the .375 H&H Mag. This was the rifle he used the longest, relied on the most and in which he had the utmost confidence. He carried that Model 70 from before World War II right through to the end of his hunting career. Johnson expected reliable performance from the Model 70, and it never let him down, which attests to the incredible workmanship and quality of the Winchester rifles from that era. Johnson’s Winchester Model 70 .375 was truly a “working” rifle that he regarded and used as a tool in the finest sense of the word.

It was the .375’s versatility that endeared Johnson and so many others to this all-around cartridge. Johnson’s son, Walter, quotes his father as saying, “I consider, and always will consider, the .375 Holland & Holland Magnum as ‘the only gun.’ In fact, I shot many hundreds of buffalo with the 9.3x62 mm Mauser to save .375 ammo, and I had no problems, but I would have preferred the .375 if I could have spared the ammo.”

Wally Johnson with a huge Mozambique elephant taken with his pre-World War II Winchester Model 70 in .375 H&H Magnum.

In 1936, Winchester chambered the Model 70 for the .375 H&H Mag. in its “standard grade.” The receiver features the early tang referred to as the “cloverleaf” or double-radius style of the prewar models versus the later postwar “straight” style. In 1956, Winchester introduced the .458 Winchester Magnum to its Model 70 lineup.

Johnson’s amazing and adventurous life was chronicled by Peter Capstick in his book entitled The Last Ivory Hunter, illustrated by Guy Coleach and published in 1988. It’s a story that Johnson recounted, keeping his safari clients spellbound around many campfires from Mozambique to Botswana and Zambia. You can be sure his .375 Winchester was always only an arm’s length away. (Read nrafamily.org/wallyjohnson for more details on Johnson’s life.)

My Own .458s

For many years, I carried a Winchester Model 70 “African” chambered for the .458 Win. Mag. cartridge as my back-up rifle while assisting hunting clients. My experience with this chambering dates back to my Kenya days in the late 1960s during which time I hunted buffalo, lion and elephant with it. It was with that same Model 70 .458 that I began hunting professionally in Botswana, and it served me well for many years backing-up clients on dangerous game. Some years later, I acquired from Harry Selby another .458 rifle built on a Mauser Model 98 action, and I semi-retired the Model 70. Availability of ammunition was the main reason I continued using the .458 Win. Mag., and I have to say that during the years I carried a .458 rifle, the cartridge never let me down. In spite of the bad press it has often received, I always found Winchester’s largest round to be a capable stopper.

Hunting elephants with clients yielded many exciting and often dangerous encounters. One particular incident stands out—when a Botswana elephant dramatically turned the tables on a safari client and me. It began when the client dropped a big bull with a single, perfectly placed brain shot. When a companion bull that had been some distance away returned to find the dead bull, he decided he was going to avenge his pal’s sudden demise. It was a strange twist, indeed, to become the hunted as we watched the bull search for us in a big, wide-open plain. We now had a fight on our hands without so much as a sapling to hide behind. And if the bull was persistent in trying to find us, I knew we faced a threat that would mean “kill or be killed!”

The bull followed scent from our tracks, which meant there was no escaping a showdown with him. I moved the client and two trackers back at a 45-degree angle from the line of retreat we’d taken from the dead elephant. I told the client to be ready to shoot as soon as the elephant reached that point and turned to face us—he would be 30 yards away, and it would confirm he was coming for us, forcing us to shoot in self-defense. When the bull reached the 30-yard mark, he turned and hardly hesitated as he came at us in a shuffling run.

“Take him now,” I told the client as we stood side by side facing the oncoming bull, knocking down tall grass as he ran. The client fired, and I fully expected to see the bull crumple but was shocked when he actually increased speed, still coming straight at us. The client’s shot had clearly missed the brain and only served to infuriate the vengeful bull even more. I was already aiming my .458, and given the low head-down angle he offered, I immediately fired at a point between and a little above his eyes. The 500-grain solid bullet smashed through the thick cellular bone structure of the skull and penetrated the brain, causing the bull’s legs to buckle mid-stride. He pitched forward, shoveling his tusks into the ground less than 15 yards from where we stood. He’d covered half the distance to us in the time it took us to fire twice.

I wasn’t aware of it at the time, but what made the situation even more dire was that the client’s Mauser-action rifle had jammed after the first shot when he short-shucked the bolt trying to rack another round into the chamber. This clearly demonstrated why a back-up rifle is so crucial when hunting dangerous game and why it needs to be in a cartridge capable of dropping an enraged elephant. Without a suitable back-up rifle coming into play, this encounter might have had a different and almost certainly tragic ending for us.

There’s almost always some amount of regret felt when an elephant goes down, but this time, we felt much more than a twinge of remorse. My respect and admiration for the amazing elephant was greatly increased, as stressful and frightening as it was to face his charge. We’d witnessed nothing less than raw emotion as one elephant tried to even the score for a dead companion.

Another remarkable, very close, shot came with my Mauser 98 .458. It happened in Botswana while looking over a herd of Cape buffalo in heavy cover. As a habit, I always carry my own rifle, which was balanced on my shoulder as I glassed the herd for a good bull from the broad base of a termite mound. My clients were a couple who, along with my two trackers, all stood, fortunately, on my right side. The herd of approximately 50 buffalo had bunched up in thick scrub vegetation about 50 yards in front of us. Suddenly and without warning, the sound of a cracking branch caught my attention, and I glanced left to see a buffalo bull burst from the bushes in full charge. An unwounded animal coming at you with all of his strength, stamina and speed intact undeniably presents a formidable threat.

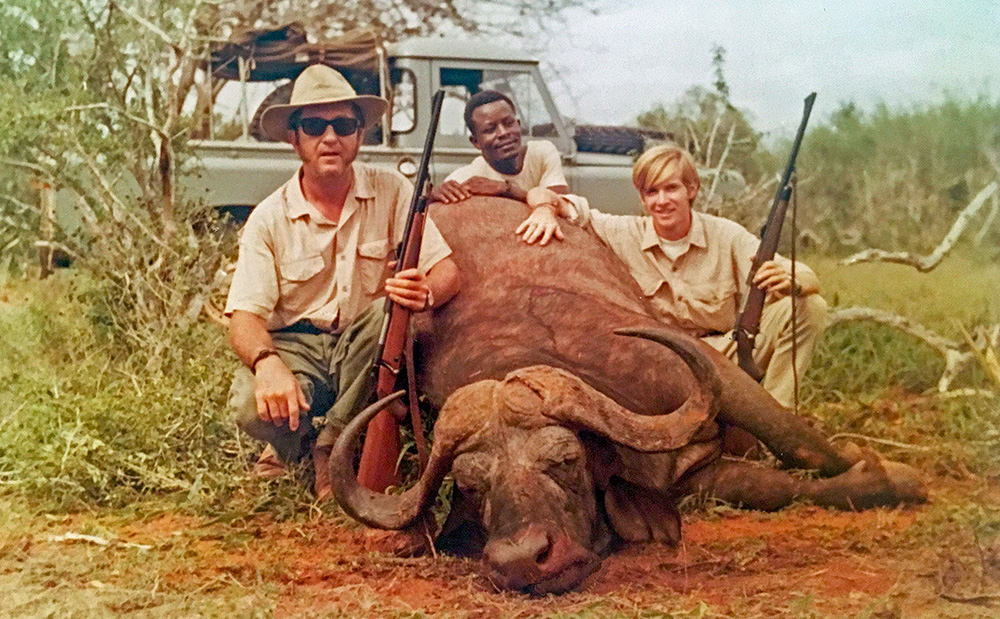

The author’s father, Joe Coogan, Sr., along with Waliangulu tracker Kiribai Bashora and the author (l. to r.) are seen here with a pair of Winchester Model 70 bolt-actions in .458 Win. Mag.

The bull meant business, and with a reflexive reaction much like snapping off a quick shot at a fast-flushing quail or pheasant, I brought my rifle to my shoulder and fired as quickly as I could. An instant, habit-ingrained reload readied me for a second shot, but the fight was over.

The 500-grain solid bullet had slammed the buff between the eyes, passed through his brain and dropped him on his nose so quickly that all I could do was stare speechless at the dead buffalo laying just seven steps away. The recovered bullet, which was found just under the thick ropey folds of skin at the back of his neck, retained its original shape. Some might say the bullet should have exited, but you’ll hear no complaints about its performance from me.

During more than 30 years of African hunting, I’ve had to stop a number of wounded buffalo, but having to shoot a previously unwounded charging buffalo occurred only once. When there’s no margin for error, you need to be sure of yourself and your rifle.

The late gun aficionado and big-bore wildcatter Jack Lott said it best when he once described the rifles he loved the most, “Big bores serve a function in providing that extra dosage of power commensurate with the greater size of the largest game and also for the stopping of charging dangerous game.” Lott did not dispute the fact that smaller conventional cartridges have all performed such work with suitable bullets at times for exceptional hunters, but he felt these feats were not to be attempted by the vast majority of us—and he was right.

Wounded Cat Guns

There’s always plenty of debate and opinion regarding whether a shotgun should be used when following a wounded leopard. Most PHs will agree that a shotgun is not sufficient for following a wounded lion, but many consider a shotgun loaded with buckshot to be sufficient for leopard. I offer the opinions of two very respected PHs here. After following many wounded leopards with shotguns during their extensive careers, both Harry Selby and Robin Hurt have said that when the incidents happened that changed their minds, given the same circumstances, they would have traded the shotgun for their big-bore rifle.

In Selby’s case, the realization that a shotgun was vastly inferior to a big-bore rifle came when he followed a wounded leopard and jumped it at around 50 yards. At that distance, he fired as the cat dashed broadside, with no visible effect. When they finally caught up to the cat and finished it, Selby was astonished to find that very few of the 00 Buck pellets had even penetrated the skin. That’s when he realized he could have ended the affair much sooner with his trusty .416 Rigby. He never again carried a shotgun on a wounded leopard follow-up.

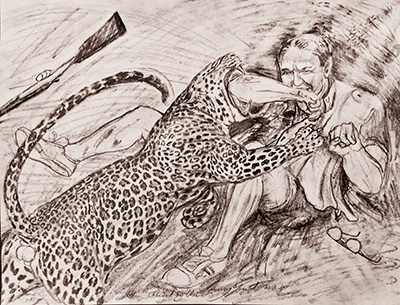

Hurt’s encounter began when his client wounded a big forest leopard on Burka Mountain in northern Tanzania. Hurt, the client and the trackers left the blind and walked to the edge of a steep ravine where they could hear the raspy breathing of the wounded cat on the opposite side. At that time, Robin felt there was still plenty of life left in the leopard. After waiting about 30 minutes, Robin positioned the client and the game scout in a place where, if the leopard left the cover, they might safely have a shot. Meanwhile, Hurt and both trackers began looking for blood in order to track the leopard. He started out with his .500 NE, and one of the trackers carried a 12-ga. shotgun loaded with 00 buck, while the other held a machete. When they reached an extremely steep place with almost impenetrably thick bush, Hurt handed his .500 to the tracker so that he could manage the steep climb. He debated taking the shotgun but did so thinking he might only have a better chance of a quick shot in the extremely close bush. As he claimed later, he always carried his double rifle following wounded game, but, much to his chagrin, on this occasion he opted for the shotgun.

They reached a place where the bush was so thick they had to bend down to get through a tunnel. At this point, the tracker with the machete moved up beside Hurt to hack a way through the thick bush. On the second whack of the machete, the leopard charged. The noise the enraged leopard made was indescribable as Hurt fired a shot at moving bushes off the end of the shotgun. The next second, the leopard was one foot from Hurt’s shotgun muzzle. He aimed deliberately at the leopard’s head, but the cat was moving fast, and the shot hit him on the side of the neck. It was so close, the pattern did not spread out, but instead penetrated down his back, leaving a solid hole. The shot had absolutely no effect on slowing the big cat.

In the next instant, it was on Hurt, and all he could see was the cat’s big head right in front of him, its teeth just inches from his face. Hurt lost the shotgun when the leopard jumped on him and now used both hands to fight the leopard and keep him from biting his head or neck. The leopard succeeded in biting Robin’s right arm, left shoulder and chest, and clawed him in various places as he tried to kick the leopard off.

The leopard ended up at Robin’s feet where he bit him through the calf quite severely. As the leopard lay there, the tracker who had taken the rifle from Robin returned to the bloody scene and, at Robin’s instruction, placed the gun against the leopard and pulled the trigger. The leopard gave no reaction to the shot, so Robin’s second shot had presumably finally killed him. The client’s initial shot had hit the leopard in the lower left front shoulder, which only succeeded in breaking the leg and leaving the cat very much alive and able to inflict serious injury.