A century-and-a-half ago, an army invaded Canada from the United States. But it wasn’t the U.S. Army. It was a force of Irish nationalists that handed the Canadians a defeat on their own soil. Under a blazing early June sun, hundreds of Americans, dressed in Union blue, Confederate gray, Irish green and civilian clothes, poured volley after volley of devastating fire from their muzzleloading rifle-muskets into a densely-packed formation of scarlet- and green-coated Canadian militiamen.

They finally forced the Canadians to break and run. To most Americans, and even to many Canadians, this improbable battle scene may sound like a scenario from an “alternative history” simulation game, or a “time-travel” science-fiction novel. Nonetheless, this battle really took place more than 150 years ago, and it is the physical manifestation of the reason why Canada became a nation in 1867.

This event also marked the last time in North America that muzzleloading arms made up the majority of arms used in a large-scale battle. The guns involved on both sides of the battle are familiar to historical firearms enthusiasts and collectors on both sides of the border. Although the two British colonies that now make up the Canadian provinces of Quebec and Ontario had administratively joined together as early as 1841, and some British regular troops were stationed in these colonies, what was then known as “British North America” (now known as Canada) was a loose collection of separate governments, and it was not very well defended.

In fact, “British North America” looked like a tempting target for American invaders at the end of the American Civil War. However, these invaders were not troops of the American government as had been the case during both the American Revolution and the War of 1812, but recent Irish immigrants who had escaped the devastating effects of the Irish Potato Famine in the mid-1840s, and had immigrated to the United States.

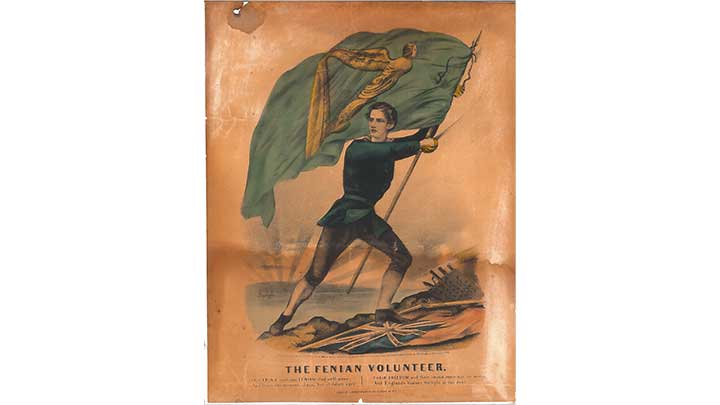

Fueled by a new militancy for Irish nationalism, many of these immigrants came to America burning with a hatred of the British and their domination of Ireland. Rejecting the failed methods of political reform, they formed a new group, called the “Fenian Brotherhood.” These Fenians organized secret cells in cities and towns across America and Ireland in the late 1850s, and began selling bonds and raising funds.

During the American Civil War, many of these Fenians served in “Irish” brigades, regiments, battalions and companies, in both the Union and Confederate armies, as well as in non-Irish formations. Understandably, there were far more Fenians in Union units, since the principal cities for Irish immigration in the 1840s and 1850s were Boston, New York, Philadelphia and Chicago.

Named for ancient Irish Celtic warriors called the Fianna, the Fenians even held conventions during the Civil War, and, right after the war ended, met together to plan an invasion of Canada. But a difference in strategies split the Fenians into separate wings. A small group that favored action in Ireland, and a much larger group which felt that Canada was ripe for invasion. They thought it could then be held hostage for Ireland’s freedom.

In public debates, both sides accused each other of not being serious about their aims, and that, along with repeated open exhortations to arms, put the Canadians on the alert. According to an article in the Philadelphia Ledger that was reprinted in the Jan. 17, 1866, of the Baltimore Sun, the British government was also very worried about the Fenian threat in Ireland and the article stated, “If the Fenians have done nothing else, they have certainly put England in a state of ludicrous fright.”

As a result, the group that favored action in Ireland, led by James Stephens and John O’Mahoney, felt pressured into initiating a premature raid into New Brunswick in April 1866. Thanks to the energetic efforts of the province, then not a part of “Canada," to reorganize and train its volunteer militia months before the crisis, the planned attack failed.

The New Brunswick volunteer militia had eagerly undergone accelerated marksmanship training, and many of them were issued modern Enfield percussion rifle-muskets. Yet the members of at least one volunteer "rifle" company were still carrying Fourth Pattern Brown Bess flintlock muskets when they turned out to confront the Fenians. The Fenians had made the mistake of smuggling most of their arms, including some seven-shot magazine-fed Spencer rifles, on a single ship, which was quickly intercepted by U.S. forces, and the arms were seized.

After a few small and brief forays across the border, the Fenians reluctantly accepted the U.S. government’s offer to pay their train fare and returned home. However, this raid, along with continued open public discussions among the Fenians about their plans for invasion, put the Canadian government on an even higher level of alert than before, and thus forced the larger group of Fenians, led by William Roberts, to accelerate their plans for a November invasion by six months.

The Fenian’s plan was sound—mass thousands of well-armed and organized soldiers, many of whom were Civil War veterans, on the Canadian border in three theaters of operation, and push northwards seizing critical towns, canals and railroads. An appeal for volunteers by the Fenian Brotherhood in the March 8, 1866, issue of the Baltimore Sun, states that the Fenians already numbered more than 300,000 members. Yet far fewer of them would ever make it to the theater of operations. One prominent historian estimates the entire Fenian Brotherhood at 47,000 members, and the Fenians' Secretary of War later stated that he needed at least 10,000 men on the border before going on the offensive.

One wing would attack from northern Vermont and drive across Quebec to Montreal. Meanwhile, the main force would cross the St. Lawrence River from New York, while a diversionary raid at Niagara would draw British troops and the Canadian militia to the south. The Fenians had been purchasing arms and equipment and secretly shipping them to points along the border, as well as organizing the rail movement of men from as far away as New Orleans. Importantly, up until the New Brunswick fiasco, President Andrew Johnson’s administration had given the Fenians the impression that the United States would do nothing to interfere with their plans, or at least the Fenians thought this to be the case.

However, with the new accelerated timetable and a political shift in Washington, things fell apart. While most of the Fenians were still en route to their mustering points, the invasion from Vermont resulted in a few small and insignificant skirmishes. Worse, the undermanned main force on the St. Lawrence front was halted when President Andrew Johnson and Secretary of State William Seward reversed course.

The U.S. hurriedly sent marshals and troops under Gen. George G. Meade, the victor of the Battle of Gettysburg, to the region after receiving promises that Great Britain seriously consider American demands for war reparations. The government officials read a “cease-and-desist” proclamation from the president and forcibly seized many of the Fenians’ arms while citing the Neutrality Act as their authority.

However, a small force led by Fenian general John O’Neil silently and successfully crossed the Niagara River from a point near Buffalo, N.Y., and began its diversionary raid in the Niagara region. Of course, all of this was happening in the days of primitive communications, so the various wings of the Fenian forces were often unaware of the events that were quickly unfolding hundreds of miles away.

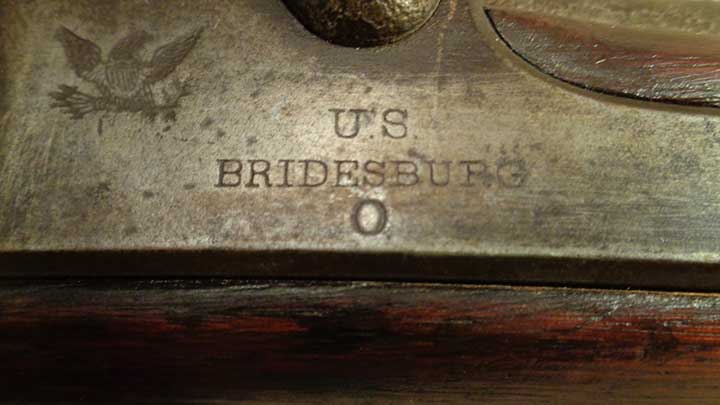

General O’Neil had about 1,000 men under his command. When the Fenians crossed over the river into Canada in the early hours of June 1, 1866, they brought with them several wagonloads of additional rifle-muskets to arm the Fenian reinforcements that were expected to join them. For a number of reasons, the reinforcements never appeared. The Fenians destroyed most of these guns, burning some and throwing the rest of them into a nearby creek. According to the testimony given by local farmers during the later trials of captured Fenians, the majority of the rifle-muskets that they recovered were Bridesburgs.

Indeed, the Fenian organization had wisely used $50,000 of the funds that had been collected over the previous years to purchase at least 7,500 rifle-muskets from the firm of Alfred Jenks & Son in Bridesburg, Penn.—a borough of Philadelphia—which was located very near the U.S. arsenal at Frankford. Jenks was a successful and well-established manufacturer and under contract, he and his son had produced more Model 1861 and Model 1863 standard “Springfield”-type .58-cal. rifle-muskets for the Union Army than any other contracted manufacturer during the Civil War.

Interestingly, extant examples of the Bridesburg-marked arms that were supplied by Jenks to the Fenians are not only the latest version of the musket, as one would imagine may have been on hand as leftovers from cancelled contracts at the war’s end, but earlier 1861 models with their locks dated “1862” and “1863.”

According to Secretary of War Stanton’s statement to Congress at the end of the Civil War, the U.S. government was not releasing surplus arms at that time, due to concerns over French intrigues in Mexico, so Jenks was one of the few arms contractors who still had enough rejected muskets (and enough spare parts on hand to build muskets) in his inventory to sell to the Fenians, as well as the ability to produce additional muskets, if needed.

In April and May 1866, thousands of Jenks’ Bridesburgs were shipped in small lots to Fenian units across the country, from Maryland, to Massachusetts, and as far west as Chicago, and then secretly stored in caches. The largest distribution (at least 1,000 rifle-muskets) was shipped to Buffalo, New York, a few weeks before the campaign began.

Many of the Bridesburgs and other rifle-muskets acquired by the Fenians were marked with an “I N” on their walnut stocks, opposite the lock and between the heads of the two lock plate screws. A commonly-held belief among arms collectors is that this marking stands for “Irish Nation” and, since forming an “Irish Nation” was the centerpiece of the Fenians’ program (and much of their patriotic art and music of the period often invoked the concept of an “Irish Nation”), this theory makes sense.

Some other surviving examples of Fenian arms also boast an “I R” (Irish Republic) and shamrock marking that was applied to the first 1,000 Bridesburgs received from Jenks, as well as to other “non-Springfield-type” rifle-muskets. Other Fenian arms have actual unit markings, or the names and ranks of individuals, stamped into their wooden stocks.

While Jenks apparently supplied fully functioning arms to the Fenians that had previously been rejected by federal ordnance inspectors for minor flaws (at least the Fenian ordnance inspector, Major William O’Reilly, never complained about them), many of the Fenian Bridesburgs that are found in collections today are composite muskets made up of mixed and badly pitted parts. One of these muskets is in the collection of Quebec’s Missisqoui Museum (across the border from Franklin, Vermont), along with other relics from the later 1870 Fenian Raid.

Aside from having various incorrect parts, some of these “composite” Bridesburg muskets are also improperly assembled, or have ill-fitting, but correct parts. Some, but not all, of the Bridesburgs also have a circular “O” stamped into the lock plate, underneath the “ES” in “BRIDESBURG”, and this is thought to be mark of a musket that was rejected by a US inspector during the Civil War. Apparently, the Fenians had reassembled these muskets incorrectly, after the U.S. government had returned their guns to them, months after they had been confiscated along the Canadian border in June 1866.

In their official correspondence, the Fenians had complained that the federal arsenals had allowed their confiscated muskets to rust, so the returned rusty guns were most likely disassembled, cleaned and reassembled by the Fenians—but often with scrambled parts—and then re-issued as rifle-muskets or converted into Needham breechloaders prior to the later 1870 Fenian Raid.

Reports from British spies noted that the Fenians also had many more rifle-muskets than the 7,500 Bridesburgs, so there were other weapons in Fenian stockpiles that had been made by a variety of other manufacturers. Fenian markings have also been found on arms other than Springfield-type rifle-muskets, and this underscores the fact that the Fenians were not confined to carrying only American-made military muzzle-loaders.

A rare example of the Pattern 1842 British musket (basically, a “Fourth Pattern” Brown Bess with an Enfield percussion lock and bolster) that was on loan to the Irish national military museum at the former Collins Barracks in Dublin was returned to Parks Canada in 2016 for display during the 150th anniversary of the Fenian Raid, and it is marked to a New York Fenian Regiment.

Moreover, in recent years, “IR/(Shamrock)” markings have been seen on both a variation of a P1858 Enfield Navy rifle, and on a Brazilian Contract Belgian “Minie Rifle," in a Gettysburg, Penn., Civil War relic shop. In addition, there is an unusual captured Fenian civilian short rifle in the collection of the local museum in Niagara Falls.

Armed primarily with their Bridesburgs, O’Neil’s Fenian force set out to capture a critical canal linking Lake Erie with Lake Ontario and started marching westwards on June 2. Meanwhile, the Canadian militia had been called out in force throughout both “Upper” and “Lower” Canada, then also known as “West” and “East” Canada, and battalions of militiamen from the cities of Toronto and Hamilton, along with companies from neighboring small towns, marched out to meet the Fenians.

Under the command of senior militia officers who apparently favored parades and drill demonstrations over real campaigning, these eager, enthusiastic and patriotic young men would find a hard fight ahead of them. In addition to fighting seasoned veterans, the Canadian militia went into battle hungry and thirsty, and with very little combat training. Indeed, the Canadian militiamen had been issued neither haversacks, nor canteens, and they had not been fed for many hours before boarding trains to the small village of Ridgeway, Ontario.

There was no organized commissariat and very little quartermaster activity. They also left their reserve ammunition behind when they disembarked from the railway cars and marched north to meet the Fenians. After the battle, a series of official inquiries were held to explain the debacle, and from the testimony in these hearings, it would appear that the bungled strategies and inattention of the senior leadership, as well as the men’s lack of marksmanship training, were responsible for the Canadians’ defeat.

While some of the militiamen were young students, and many of the others were less than 20-years-old, they did have a few veterans in their ranks that had seen service in British army. Some of these veterans were serving as junior officers and NCOs. However, many of the young men under the command of these few veterans had never even fired blank charges through their guns, and only a handful had ever fired live rounds.

Worse yet, many of their arms were in deplorable condition. This was in marked contrast to the experiences of the New Brunswick men a little over a month earlier. For the most part, the Canadian militia was armed with variations of the .577-cal. Pattern 1853 Enfield rifle-musket.

One company of the Queen’s Own Rifles from Toronto went into battle with nearly 50 .52-cal. (.56-50 Rimfire) Spencer repeating rifles and carbines. The Spencers had just been issued to the company, and none of the militiamen had any training on their use and operation. Even worse, each man only received 28 rounds of ammunition.

With the exception of the Spencers, most of the Canadian rifles, carbines, and muskets very likely were marked “UC” (Upper Canada) on their butt plate tangs, in accordance with an 1856 militia directive, although the region generally was now known as “West Canada.” (David W. Edgecombe’s excellent book, Defending The Dominion: Canadian Military Rifles, 1855-1955, contains a detailed description and analysis of these markings.) One “Type II," or “Windsor” pattern Enfield on display in a Brantford ON military museum has “QOR” stamped on its brass butt plate tang.

While trying to link up with a nearby combined force of British regulars and other Canadian militia units, and with the Spencer-armed company at the head of the column, the Canadian militiamen blundered into the advancing Fenians at Limestone Ridge, North of the small village of Ridgeway. Disastrously, the Canadian militia forces were on the wrong road at the wrong time to make the planned juncture with the larger force that was marching to the Southwest from the town of Chippewa. Nevertheless, they drove back the skirmish line of Kentucky Fenians.

Yet when they hit the main Fenian force on the ridge line, the Fenians poured volleys into them with such rapidity and volume that some Canadian militiamen later swore that the Fenians were all armed with “repeaters.” While running low on ammunition, a panic over a false alarm of a supposed cavalry attack caused the Canadians to “form square,” but the command was not well executed, as the units had become intermingled. After a few more thunderous volleys from the Fenians, the Canadians broke and ran.

O’Neil, realizing that reinforcements were not forthcoming and that U.S. authorities may cut off his retreat, did not follow up on his victory but instead retired eastwards to Fort Erie, where he ran into a boatload of Canadian militia that had been sent to cut him off.

As recounted in the proceedings of the later official inquiries, and in several memoirs, this composite Naval/Artillery unit was armed with “Short Enfields”, “Long Enfields” and .73-cal. “Victoria” carbines—an obsolescent and cumbersome cavalry carbine with a reportedly wicked recoil— during their ill-fated amphibious landing.

When the senior Canadian officer panicked and hid, his command was badly handled by the Fenians. The Canadians could not stop the Fenians from boarding an immense barge and making their escape at nightfall.

However, a U.S. warship captured the barge in mid-river. After being arrested by U.S. Marshals, most of the Fenians were sent home, courtesy of the U.S. government, as had been done in Maine a month earlier. The effect of the Fenian Raid and the battle of Ridgeway was to still all opposition to the momentum that had been pushing most of British North America into a confederation as a single British Dominion.

This question had been hotly debated among Canadians for years prior to 1866, but the need for a concerted response to threats against their country’s defense was now glaringly obvious. Accordingly, the Dominion of Canada was born in the following year. In honor of the occasion, one wounded veteran of Ridgeway later composed what would become Canada’s unofficial anthem for many years thereafter, “The Maple Leaf Forever.”

However, the Fenian threat did not go away, and, in 1870, the Fenians tried to invade again from Vermont. This time, unlike at Ridgeway, they were armed with Needham conversion breech-loading rifles. They were also fighting against determined Home Guardsmen carrying Ballard breechloaders, as well as Canadian militiamen with their Snider breechloaders.

The author thanks Bill Adams, the late Tom Butler, Earle Coates, Paul Davies, Donna Elliott, Ross Jones, Lar Joye, Christophe Mueller, Steve Nugent, Chris Nugent, David Sullivan, Tim Warnick and the staffs of the Missisquoi Museum, the Brantford Military Museum and the Fort Erie Museum for their kind assistance in the preparation of this article.

For additional information about Private Copp’s Spencer rifle, and Fenian Bridesburg muskets and Needham conversions go to: Icomam magazine and military-historians.org/company/journal/journal.htm.