The second largest armed insurrection in American history, only surpassed by the American Civil War, culminated in the Battle of Blair Mountain, near the town of Logan, W. Va., during the late summer of 1921. Thousands of coal miners, pushed beyond the limits of frustration with the coal mine owners and operators, took up arms and marched from the state capital, Charleston, toward the southernmost county in the state, in a spontaneous attempt to free fellow miners who had been capriciously imprisoned by local authorities for attempting to unionize the coal fields. Rumors of the recently formed state police machine-gunning women and children in the camps of striking miners fueled the fires of their rage, and revenge for the assassination of their hero, Sid Hatfield, steadied their course. When the marching miners met the hurriedly assembled forces of Sheriff Don Chafin at Blair Mountain, they were carrying a wide array of firearms, while the Logan County Defenders, manning the trenches on the top of the mountain, had an equally disparate assortment of guns.

For decades prior to 1921, there had been unrest in the mining industry across the nation. In their attempts to squeeze every penny of profit out of their enterprises, many mine owners and operators not only employed unfair labor practices that forced many miners into a form of economic slavery, but also tolerated unsafe conditions that led to the deaths of hundreds, if not thousands, of miners. The only redress on the part of the miners was the growing labor union movement, and by the summer of 1921 only the southern West Virginia coalfields had not yet been unionized. The mine operators there fiercely resisted unionization, as the post-World War I recession had cut deeply into their profits and, through a series of manipulations and machinations, they had the local and state authorities either firmly on their side or in their pockets. The miners’ repeated appeals to the federal government for help went, for the most part, unanswered.

In 1913, striking miners and their families living in a tent camp had been machine-gunned from a hastily improvised armored train, manned by men of the notorious Baldwin-Felts Railroad Detective Agency, who were actually serving as mine guards and company “enforcers.” The resulting fracas at Paint Creek and Cabin Creek brought in the West Virginia National Guard to disarm the miners, after a negotiated settlement was reached. Relations between the operators and the miners improved during the boom years of World War I, but steadily deteriorated after the war. They finally came to a head in May 1920, when a shoot-out in the streets of the small mining town of Matewan, in Mingo County, resulted in the deaths of several “detectives” at the hands of the local authorities, who, in turn, were supported by armed miners. The town chief of police, “Smiling Sid” Hatfield (one of many of that famous local clan who were involved in the Coal Mine Wars), was a former miner and had stood up to the mine operators’ hired guns who were illegally and unceremoniously evicting the families of striking miners from company-owned houses.

After being tried for murder and acquitted, Hatfield, now the hero of the miners, was  summoned to testify before the U.S. Senate a year later. Meanwhile, a war between the mine operators and the striking miners had been raging in Mingo County, with miners and mine guards (usually referred to as “gun thugs” by the miners) trading shots at each other daily, sometimes with serious casualties. Across the Tug River in Kentucky, tensions were also running high, with frequent shootings between miners and the Kentucky National Guard on both sides of the river. The governor of West Virginia responded by proclaiming martial law in Mingo, although he had no troops with which to enforce it, since West Virginia had not re-established its national guard after it was federalized for overseas service in World War I. The job fell to the newly established West Virginia State Police, supported by both mine guards and a local militia made up of the middle class and professional men of the county. Using their newfound powers, the authorities in Mingo County began jailing any miner suspected of union activity, without charge. Scores of miners were locked up in makeshift jails, and the authorities banned nearly all of the union’s activities.

summoned to testify before the U.S. Senate a year later. Meanwhile, a war between the mine operators and the striking miners had been raging in Mingo County, with miners and mine guards (usually referred to as “gun thugs” by the miners) trading shots at each other daily, sometimes with serious casualties. Across the Tug River in Kentucky, tensions were also running high, with frequent shootings between miners and the Kentucky National Guard on both sides of the river. The governor of West Virginia responded by proclaiming martial law in Mingo, although he had no troops with which to enforce it, since West Virginia had not re-established its national guard after it was federalized for overseas service in World War I. The job fell to the newly established West Virginia State Police, supported by both mine guards and a local militia made up of the middle class and professional men of the county. Using their newfound powers, the authorities in Mingo County began jailing any miner suspected of union activity, without charge. Scores of miners were locked up in makeshift jails, and the authorities banned nearly all of the union’s activities.

Shortly after his appearance before the U.S. Senate, Sid Hatfield and a long-time friend, accompanied by their wives, were lured to the neighboring county of McDowell, to answer a spurious indictment. Without provocation, a group of Baldwin-Felts detectives gunned down the two unarmed men, in front of their horrified wives, on the steps of the county courthouse in the town of Welch. Hatfield’s assassination, and the oppression of the striking miners in Mingo, galvanized coal miners across the state. Urged on at several mass meetings by “Mother” Mary Jones, an elderly, feisty and outspoken labor agitator, the miners grabbed their guns and headed south to Mingo, in an ever-growing stream of armed men.

In response to the governor’s pleas, the Harding administration sent Maj. Gen. Harry Hill  Bandholtz to defuse the situation. The former Provost Marshal of the American Expeditionary Forces, he was an accomplished diplomat. In 1919, armed with only with his M1911 Colt pistol and a riding crop, he had single-handedly saved the Hungarian national museum in Budapest from destruction by confronting a mob of victorious Romanian soldiers bent on looting it. Bandholtz convinced the local leaders of the United Mine Workers of America to stop the march. Most of the miners turned around and began to return home, but Capt. James R. Brockus of the West Virginia State Police seized the opportunity to arrest some miners who had earlier humiliated some of his troopers by disarming them. Leading about 300 men, some armed with Thompson submachine guns, on a night raid, Brockus ended up in a fire fight with alarmed miners living in one of the mining camps. During the melee, several miners were killed and wounded, while their homes were sprayed indiscriminately with gunfire.

Bandholtz to defuse the situation. The former Provost Marshal of the American Expeditionary Forces, he was an accomplished diplomat. In 1919, armed with only with his M1911 Colt pistol and a riding crop, he had single-handedly saved the Hungarian national museum in Budapest from destruction by confronting a mob of victorious Romanian soldiers bent on looting it. Bandholtz convinced the local leaders of the United Mine Workers of America to stop the march. Most of the miners turned around and began to return home, but Capt. James R. Brockus of the West Virginia State Police seized the opportunity to arrest some miners who had earlier humiliated some of his troopers by disarming them. Leading about 300 men, some armed with Thompson submachine guns, on a night raid, Brockus ended up in a fire fight with alarmed miners living in one of the mining camps. During the melee, several miners were killed and wounded, while their homes were sprayed indiscriminately with gunfire.

Exaggerated rumors about the “Sharples Massacre” quickly reached the retreating miners, and they turned around, heading south again-but now with a vengeance-and appropriated more guns and ammunition from citizens and businesses along the route of the march. On the way, the miners also commandeered motor vehicles, as well as entire railroad trains. More miners joined the throng, now just one county away from their destination-Mingo County. The armed marching miners (estimated at anywhere from 7,000 to as many as 20,000) then hit fierce resistance at the entrance to Logan County, where a formidable defensive line of World War I-style trenches had been constructed on top of Blair Mountain by Sheriff Don Chafin’s Logan County Defenders.

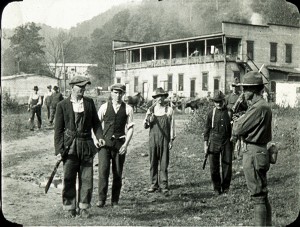

Chafin was a resolute and implacable foe of the union. He was also obviously in the pay of  the mine owners and operators, in that he died a very wealthy man in the 1950s, after having received only a meager salary during his life-long employ as county sheriff. The mine operators paid the salaries of his many deputy sheriffs, since they also doubled as mine guards, “keeping order” in the mining camps. Chafin played on the fears of the citizens of the region, by equating the miners and unions with bolshevism, an already prevalent opinion openly shared by the Attorney General of the United States. While many of the miners were recent immigrants, or the sons of eastern and southern European immigrants, and some shared a more socialistic view of politics than many Americans at the time, the overwhelming majority of them were patriotic Americans, simply seeking a decent life and the American Dream. Moreover, a sizeable percentage of the overall-clad miners were veterans of World War I, and many of them brought their “tin hats” and gas mask bags along with them. Many of the marching miners and at least two of their leaders were African-American-perhaps another fear that was exploited.

the mine owners and operators, in that he died a very wealthy man in the 1950s, after having received only a meager salary during his life-long employ as county sheriff. The mine operators paid the salaries of his many deputy sheriffs, since they also doubled as mine guards, “keeping order” in the mining camps. Chafin played on the fears of the citizens of the region, by equating the miners and unions with bolshevism, an already prevalent opinion openly shared by the Attorney General of the United States. While many of the miners were recent immigrants, or the sons of eastern and southern European immigrants, and some shared a more socialistic view of politics than many Americans at the time, the overwhelming majority of them were patriotic Americans, simply seeking a decent life and the American Dream. Moreover, a sizeable percentage of the overall-clad miners were veterans of World War I, and many of them brought their “tin hats” and gas mask bags along with them. Many of the marching miners and at least two of their leaders were African-American-perhaps another fear that was exploited.

Against these “Redneck” Miners (so-called because their only uniform was a red bandanna, usually worn around the neck), Chafin was able to assemble an “army” of West Virginia State Police, the neighboring Mingo County “Citizens’ Militia,” hundreds of his own deputies, volunteers (including many World War I veterans, mainly officers) from across the state, American Legion detachments from all over the state, willing businessmen and professionals (and others who simply were anti-union) from the local area, unwilling local citizens who, nevertheless, were quickly issued guns and sent to the front lines, and non-union miners who were threatened with dismissal if they refused to fight in Chafin’s “army.” There were no formal mustering processes or record keeping, so estimates of the number of men enrolled in the Logan County Defenders vary-somewhere between 2,500 and 3,500-and the “army” was nominally under the command of Col. William E. Eubank, who, at the same time, was frantically trying to reconstitute the state’s national guard. However, it was no secret that Chafin, who had energetically acquired or commandeered every firearm at his disposal in the county, was really running the show. He even enlisted several civilian pilots who dropped improvised fragmentation and chemical bombs on the miners from their biplanes.

It is safe to say that at least one example of nearly every firearm produced in the United  States between the end of the Civil War and August 1921 saw service with either the Logan County Defenders or the “Redneck” Miners. Not only had Don Chafin emptied every hardware store in the county of its guns and ammunition (as well as having acquired current-issue military arms and ammunition from the state armory in Charleston) but his volunteers showed up with an unimaginable assortment of their own guns. Civilian hunting rifles, shotguns and handguns of all makes, models, calibers and gauges are described in the accounts of the period, as too are surplus obsolescent military arms (including some foreign designs), and even some muzzleloaders. In addition, there were large numbers of Thompson submachine guns, as well as Winchester Model 1897 riot shotguns, available to the Logan County Defenders. American Legionnaires carried the surplus U.S. Krag rifles that had been distributed to Legion posts nationwide by the U.S. government only the year before. Mine-company-owned Colt-Browning “potato digger” machine guns were pressed into service, and there are reports of Gatling guns and perhaps even some then-current U.S.-issue automatic arms being used.

States between the end of the Civil War and August 1921 saw service with either the Logan County Defenders or the “Redneck” Miners. Not only had Don Chafin emptied every hardware store in the county of its guns and ammunition (as well as having acquired current-issue military arms and ammunition from the state armory in Charleston) but his volunteers showed up with an unimaginable assortment of their own guns. Civilian hunting rifles, shotguns and handguns of all makes, models, calibers and gauges are described in the accounts of the period, as too are surplus obsolescent military arms (including some foreign designs), and even some muzzleloaders. In addition, there were large numbers of Thompson submachine guns, as well as Winchester Model 1897 riot shotguns, available to the Logan County Defenders. American Legionnaires carried the surplus U.S. Krag rifles that had been distributed to Legion posts nationwide by the U.S. government only the year before. Mine-company-owned Colt-Browning “potato digger” machine guns were pressed into service, and there are reports of Gatling guns and perhaps even some then-current U.S.-issue automatic arms being used.

The miners had the same range of armament, but with many more civilian shotguns, and with very few current-issue military rifles and machine guns. According to the lists kept by the West Virginia National Guard of the massive turn-in of guns after the 1913 Paint Creek/Cabin Creek episode, the majority of the arms surrendered by the miners were Winchesters, “Trapdoor” Springfield rifles, shotguns and Colt revolvers. The miners of 1921 would have had a similar, but much expanded, group of shoulder arms and handguns.

Of the cornucopia of arms used at Blair Mountain during the Coal Wars, three can be singled out as being emblematic of the fight: the Model 1873 Winchester rifle; the Swiss Vetterli rifle; and the Thompson submachine gun. The Winchester was one of the rifles most often seen among the ranks of the miners, the Vetterli was considered the “poor man’s bear gun” and was a favorite in the region, and the Thompson submachine gun apparently earned its place in history as a significant game changer in battle at Blair Mountain.

Nearly every extant photograph of the armed miners shows at least one of them with a Model 1873 Winchester rifle in his hands. Already a favorite of hunters for more than 45 years and just out of production at the time, the lever-action Winchester rifle, chambered mostly in .44-40 Win. (or .44 WCF), but also in .38-40 Win., .32-20 Win., and even .22 rimfire, carried a minimum of 12 rounds in its tubular magazine beneath the barrel, depending on the caliber. Accurate and handy, the Winchester had a smooth toggle-link action that allowed the firer to shoot multiple successive rounds from the shoulder without interrupting his aim, unlike the case with many bolt-action rifles. While other lever-action rifles are also seen in surviving photographs, and are noted in documentary sources, the Model 1873 rifle is by far the most prevalent.

The Swiss Vetterli was the most advanced military rifle in the world when it was adopted in 1868. Combining the bolt-action of the German needle gun and the tubular magazine of the Winchester, it fired a 10.4x38 mm (.41 Swiss) rimfire, blackpowder cartridge from a 12-round tubular magazine. When Switzerland adopted the Schmidt-Rubin 7.5x53.5 mm straight-pull rifle in 1889, the country had thousands of Vetterli-designed military rifles on hand. These accurate, but now obsolescent arms were then dumped on the world market, with many of them being sold in America by the famed surplus dealer Francis P. Bannerman of New York, and by both Montgomery Ward and Sears, Roebuck & Co. through their widely successful mail-order businesses. There were several variants of the Swiss Vetterli produced, but the version most commonly encountered in the Appalachian Mountains was the full military rifle, although they were often “sporterized.” While a Winchester Model 1892 rifle sold for $13.16 in the 1908 Sears, Roebuck & Co. catalog, a Swiss Vetterli cost only $7, and among the poor mountaineers, this was a significant advantage. Additionally, the .41 Swiss round was far more powerful than the .44-40 Win. revolver cartridge-definitely a consideration when hunting black bear.

The Thompson submachine gun emerged in early 1921, and its first use in combat most often is ascribed to an ambush of a British troop train at the Dublin suburban railway station of Drumcondra. There, on June 16, 1921, two members of the Irish Republican Army used two Thompson guns (one of which immediately jammed) to shoot up several railway carriages carrying a detachment of the Royal West Kent Regiment. Nevertheless, three days before the Drumcondra attack, West Virginia State Police troopers used Thompson submachine guns to “sprinkle” the mountainside near Lick Creek, where striking miners were firing at passing automobiles. The police and militia then returned later in the day, and fought a pitched battle in the miners’ tent colony, resulting in the death of a striking miner.

Of the 3,250 Thompson submachine guns produced in the months prior to August 1921, the West Virginia State Police, at the time numbering only about 100 troopers, had acquired at least 37 of them. And since about 70 troopers were then staged in Mingo, it is safe to assume that they brought with them to Logan as many submachine guns as were available in State Police armories. Moreover, according to the serialized manufacturing and shipping lists in Tracie Hill’s definitive book on the Thompson, a minimum of 56 guns had not only been acquired by the coal companies in the southern West Virginia coalfields for their guards, and by local law enforcement officers, but the guns were also being shipped to hardware stores in the region-all prior to the battle of Blair Mountain. The Logan Hardware and Supply store received no fewer than nine “Tommy Guns” in April and May alone. There are extant photographs of Thompsons being carried in the streets of Logan at the time of Blair Mountain, and when Sheriff Chafin appealed for volunteers from across the state, he specifically asked them to bring “raincoats and any automatic weapons” that were available.

Most chroniclers of the Battle of Blair Mountain refer to “machine guns” having been used, and the most often published photograph of the fight (and one of the very few known actual combat images) shows a Colt “potato digger” tripod-mounted machine gun in action with the Logan County Defenders. While there certainly were crew-served machine guns on both sides, they can hardly account for the constant roar of gunfire up and down the more than 10-mile line of earthworks and barricades, as was reported in all of the accounts of the battle. Many of these reports came from World War I veterans, who had plenty of experience in determining the extent of gunfire. Indeed, one of the most readable books about the battle is even titled Thunder in the Mountains. The Model 1921 Thompson’s very high cyclical rate of fire (about 900 r.p.m.), and the use of 100-round Type “C” drum magazines, as well as 50-round Type “L” drum magazines, certainly would have been a critical ingredient to the reported overpowering din of battle.

Finally, reports from a team of archaeologists that conducted a survey of the battlefield in 2006 indicate that a surprisingly large number of spent .45 ACP cartridge cases have been found in groups on the battlefield, and these findings would support the statement that the Battle of Blair Mountain was the first significant appearance of the “Tommy Gun” as a pivotal element in battle. Some of the miners later admitted that every time they advanced up one of the many hollows leading to the top of the mountain, they were met with withering and constant gunfire, a testament to the likely widespread use of Thompson guns by the Logan County Defenders. Sadly, further properly funded and directed professional excavations of the battlefield most probably will not happen again in the future, given the current fiscal climate, and the fact that the battlefield itself may very well become a victim to mountaintop extraction methods of coal removal before such searches could occur.

Casualties on both sides are estimated to be from a low of 30 to as many as several hundred. The fighting raged on for five days, during which time Bandholtz summoned U.S. regular infantry from Ohio, Indiana and New Jersey. Not without mishap, the controversial aviation pioneer Brig. Gen. “Billy” Mitchell flew in a squadron of DeHavilland fighter-bombers from Langley Field in Virginia and a squadron of Martin bombers from Bolling Field in Washington, D.C. Faced with this threat, and not wanting to fight the troops, the miners abandoned the assault, surrendered some arms (but hid the rest), and went home. Their fight was not with the federal government, but with the coal mine owners and operators, and those who supported them. As loyal U.S. citizens, the miners did not consider themselves to be insurrectionists in revolt against “Uncle Sam.”

More than 100 miners were arrested and tried for treason at the same courthouse in which the abolitionist John Brown had been tried for the same crime more than 60 years before, but nearly all of them eventually were acquitted. The march, the battle, and the expense of the trial broke the back of the UMWA in the region, and the southern coalfields were not completely unionized until the eve of World War II. Outside of West Virginia, the story of the march and the battle has not been told until recent years, and questions concerning the rights of labor, capitalism, unions, militias, police, insurrection, government, vigilantes, confiscation, the First Amendment and the Second Amendment are as relevant today as they were back then. While perhaps neither the Redneck Miners, nor the Logan County Defenders, had all the answers to these questions, they at least had their guns when they needed them.

Postscript: While serialized lists of arms surrendered by the miners after Blair Mountain have not yet been located, a report made by an officer of the Logan County Defenders during the battle noted that Springfield M1903 rifles, serial numbers: 51408; 401234; 41994; 189490; 83361; 310380; 462717; 72103; 50074; 581486; 307885; and, 39634 had been “found in Wilkinson Yard.” Is one of these rifles in your gun cabinet?

The author thanks Michael Shyne, Stephen Smith, Al Houde, Brandon Nida, the National Firearms Museum, the Coal Wars Living History Project, and especially Kenneth King, for their assistance in the preparation of this article. Not only did King provide the period photographs from his collection-he broke his foot while taking photos of the battlefield relics!

Photo courtesy of Kenneth King, West Virginia and Regional History Collection