The spring of 1945 was filled with countless stories of triumph and tragedy, and one inescapable fact: the advance of the U.S. Army into the heart of Germany was unstoppable. By March 1, American troops had forced their way through Duren and across the Roer River. The advance surged onto the Duren-Cologne highway and spread out across the Cologne plain. The race toward the Rhine River was on.

At that time my father, Sgt. Carl Laemlein, was with the 13th Infantry Regiment of the 8th Infantry Division. After the breakthrough at Duren, his regiment was attached to the 3rd Armored Division, one battalion assigned to each combat command, beginning on the morning of February 26. Each combat command was divided into two task forces, made up of a tank battalion and a battalion of armored infantry, along with a tank battalion coupled with a battalion of the 13th Infantry Regiment with the other.

The 3rd Armored tanks passed through Duren on the morning of February 26, picking up the 13th Regiment infantrymen before they clattered their way on towards Cologne. The 13th Infantry G.I.s rode atop the M4 Sherman and new M26 Pershing tanks, the troops clinging on to the turrets and engine decks as best they could. My father described the experience of riding on the tanks as “uncomfortable, but better than walking." Even though the tanks gave the infantrymen a new boost in mobility and firepower, they also presented an inviting target.

While Germany’s Panzer divisions had been badly routed in the Battle of the Bulge at the beginning of 1945, German anti-tank defenses were stronger than ever. Anti-tank guns along with handheld Panzerfaust and Panzerschreck anti-tank rocket launchers took a terrible toll on American tanks. As an infantryman, my father was not a fan of armored vehicles: “Those damned things have an awful tendency to draw fire and then catch fire." Having the infantry ride on the tanks into battle was a dangerous gamble, but even the weary foot soldiers could see this was a great opportunity to move quickly and end the war sooner.

Cologne was Germany’s third largest city and ultimately the biggest German city that the US Army would assault. On the approaches to the city, the armor and infantry combat commands would meet stiff resistance, but the combination of firepower and mobility would quickly overwhelm German defenses in towns like Golzheim, Blatzheim, Buir, Manheim, Etzweiler, Giezendorf, Heppendorf, Widdendorf, Berrendorf and Paffendorf. In each town, the actions were much the same—the infantry would root out the German defenders and find the strong points. Then the tanks would come in and eliminate the bunkers and the process would be repeated in town after town.

The Erft Canal presented another potential barrier, but after some intense fighting, the fast-moving combat commands captured a bridge intact near Gleich. Before the Germans could counterattack, the troops of the 13th Infantry Regiment’s 3rd Battalion had crossed the Erft canal and established the first bridgehead across the last water barrier west of Cologne.

The 13th Infantry Regiment’s official history records: “It is felt that in no battle was the 13th Infantry's pressure of more importance in the outcome of the war than in this drive with the Third Armored Division. During the period February 27 to March 6, the drive of the Third Armored Division split the German defenses west of the Rhine and sent them reeling to the rear. The 13th Infantry soldiers were riding the tanks and attacking with a ferocity which was unusual even for them. At no timewere they halted, and the aggressiveness of the Regiment won the praise of all the commanders of the Third Armored Division, the Corps Commander and the Army Commander.”

The Germans struck back desperately against the small bridgehead across the Erft, and 13th Infantry G.I.s on the east side of the canal fought off five strong counterattacks that included tanks. Meanwhile, combat engineers reinforced the captured bridge to allow the 3rd Armored Division’s tanks to cross and keep the pressure on the Germans. The advance on Cologne would continue, fast and furious.

German tanks counterattacked at Busdorf and two 2 ½ ton trucks full of G.I.s were hit—on one of the trucks every man was either killed or wounded. Even so, the American attack pressed on. At Stommeln, the dismounted infantry engaged in a brutal night fight with German defenders that included four Sturmgeschutz assault guns. Bazookas and satchel charges ended the enemy armor threat. Again, the American attack pressed on.

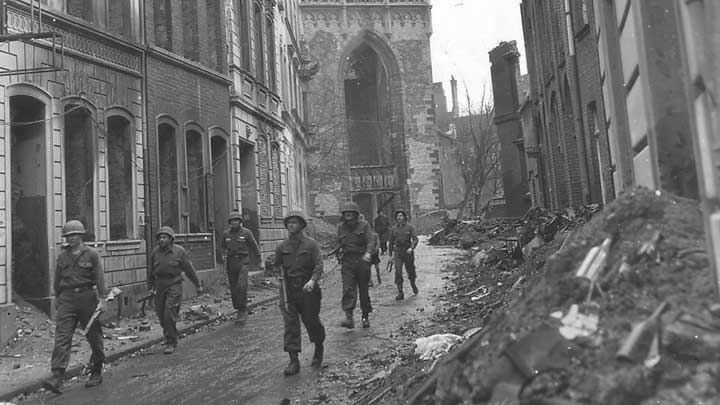

By the time that the Combat Commands of the 3rd Armored Division and the 13th Infantry Regiment reached Cologne, the ancient German municipality was a shattered city. Since the spring of 1940, Cologne had been subjected to 262 separate air raids, all but one conducted by the Royal Air Force (R.A.F.). Almost 35,000 tons of bombs had been dropped on the city, killing more than 20,000 of Cologne’s residents. On the night of May 30, 1942, the R.A.F. targeted Cologne with its first 1,000 bomber raid. Many parts of the city were filled with craters and entire blocks were burnt out. By March 1945, Cologne was a prime example of total, modern war.

Inside the city, the iron hand of the Gestapo had clamped down on the population. The ruins of Cologne housed many strange groups beyond the hapless, bombed-out residents. Many deserters from the Wehrmacht service had congregated there, along with teenagers avoiding military labor duty, conscription into Hitler Youth units or “Flak helper” service. Cologne was also the home of one of the Third Reich’s most active resistance movements, the teenagers of the “Edelweiss-Piraten."

These anti-Nazi Germans had carried out many attacks against Nazi party officials since the summer of 1944, and after a number of full-scale firefights between the Edelweiss cells and Gestapo units, Reichsfuhrer Heinrich Himmler ordered stiff reprisals, including mass public hangings, against the “terrorist gangs” of Cologne. Nazi Germany’s final weeks during the spring of 1945 were an all-consuming firestorm of death and destruction. Cologne was a prime example of the madness.

On March 2, 1945, as the Americans approached Cologne, the R.A.F. flew its last raid on the city in which 858 British bombers laid down a devastating carpet of high explosive across the already smashed community. Many hundreds of civilians were killed in the attack, and the city defenders had no time to bury the bodies as they prepared for the American advance that was soon to come. The G.I.s were shocked to find so many dead when they entered the city, beginning on the morning of March 5.

With the 13th Infantry Regiment and the 36th Armored Infantry Regiment riding on their tanks or in accompanying halftracks, the 3rd Armored Division deviated from standard US Army doctrine and sent an armored force into an enemy city. In this case, the speed of the advance coupled with the value of the target was judged to be worth the risk. US tank and infantry combat commands crashed into Cologne while it was still dark on the morning of March 5. House-to-house fighting erupted in several areas of the city, but American troops quickly made important breakthroughs with the help of fire support from the 3rd Armored’s tanks. However, snipers lurked everywhere in the ruins and it would take some time to root them all out.

At the main airfield at Butzweilerhof, the Germans made good use of the 16 entrenched 88 mm Flak guns there. Several US tanks were knocked out before Task Force Kane embarked on a wild charge across the field. Aided by a smoke screen, and with men of the 13th Infantry Regiment fighting from the backs of vehicles, the Sherman tanks clattered across the open ground at top speed. My father commented: “You held on for dear life with one hand while you shot at the Germans with the other.” He made a couple of other comments about the action which can’t be repeated here.

Throughout the area, particularly approaching the Rhine, the fighting was furious throughout the day. The combat was intense for short bursts, then suddenly quiet before just as quickly restarting. The behavior of many of the German civilians was confusing and erratic, some were shell-shocked. Some were openly trying to defend their city while in civilian clothes. Others greeted the American troops not as invaders, but rather as liberators. Some residents wandered out to watch the fighting and ended up getting shot in the process.

As Cologne was an important prize to be captured, it was a significant story for the press. A large amount of Press Corps and Signal Corps members were in Cologne, and some became casualties. The peaked caps they wore were very similar to those worn by German Volksturm and Hitler Youth units. Press members were strongly advised to wear their M1 steel pot helmets, for protection against shrapnel and to aid in identification.

At midday on March 6, as the Americans approached the river, the Germans blew up the Hohenzollern Railway Bridge across the Rhine. U.S. forces would have the city, but not its massive bridge. One final dramatic combat would take place in the shadows of Cologne’s famous cathedral. A German Panzer V “Panther” tank was positioned there as a column of 3rd Armored M4 Sherman tanks approached. The German’s nailed the lead tank with two 75 mm high-velocity armor-piercing round that killed three of the Sherman’s five crewmen.

Alerted by the Sherman column, a U.S. M26 “Pershing” heavy tank flanked the Panther on a parallel street at close range. Hit three times by the Pershing’s 90 mm gun, the Panther burst into flames. This action was caught on film by Army cameraman Jim Bates. The M26 had only recently been introduced into combat, and the sprint for Cologne had been the vehicle’s first significant action. American tankers were very pleased with its thicker armor and more powerful gun, but only 20 would make it to the European Theater of Operations before the end of the war.

By the end of the day on March 7, German resistance in Cologne was smashed. The mass of citizens, refugees and foreign laborers in the city went on a two-day binge of frenzied looting. American M.P.s moved in to restore order, although extreme measures had to be taken. Curfews were strictly enforced. All arms and ammunition were collected up, and every building was searched for war materiel as well as Nazi officials attempting to hide. The 104th Infantry Division moved into the city and along with the US Military Government Detachment, day-to-day administration of the city was restored.

Despite all the bombing raids throughout the war and the furious land battle at the end, Cologne’s famous Gothic cathedral was still standing. It had been hit numerous times, but through some incredible miracle, the cathedral was not badly damaged. The impressive structure was an icon of peace and faith amid all the madness. My father always had an appreciation for architecture.

Unfortunately, most of the ancient buildings he saw during his time in Europe had been demolished in the fighting. He marveled at the cathedral, its spires rising above the rubble. Dad talked about it late in his life: “Even with all the bombing, and then what our artillery blew up, and then whatever was left of that city we shot holes in—despite all that the cathedral was still standing. I guess the Good Lord really liked that church, because he’s the only one who could’ve saved it.”