The now-legendary “U.S. Rifle, Caliber .30, Model of 1903” was adopted in 1903, and it became one of the most widely used and best-known American military rifles of all time. Rare indeed is the shooter, collector or arms enthusiast who is not familiar with the ’03. Not so well-known are the significant changes made in the rifle during the first three years of its existence.

When originally adopted, the M1903 rifle was different in several respects from the pattern so familiar today, including the configuration of the stock, handguard and sights. Two of the most significant differences found in the original variant of the ’03 rifle were the integral sliding “rod bayonet” and the fact that it was chambered for the Model of 1903 cartridge. This .30-cal. smokeless-powder cartridge, often referred to as the .30-’03 (.30 caliber, adopted in 1903), had a round-nose 220-gr. bullet, similar to that of its predecessor, the .30-40 Krag.

The M1903 rifle was put into production at Springfield Armory and Rock Island Arsenal soon after its formal adoption. By January 1905, there were sufficient numbers of the new rifles on hand to begin limited issuance to the U.S. Army. However, concerns about the bayonet soon began to surface. President Theodore Roosevelt, in particular, was not at all happy with the flimsy rod bayonet and stated his feelings in a Jan. 4, 1905, letter to the secretary of war. The concluding paragraph of the letter contained the unequivocal statement: “I must say that I think the ramrod bayonet is about as poor an invention as I ever saw.”

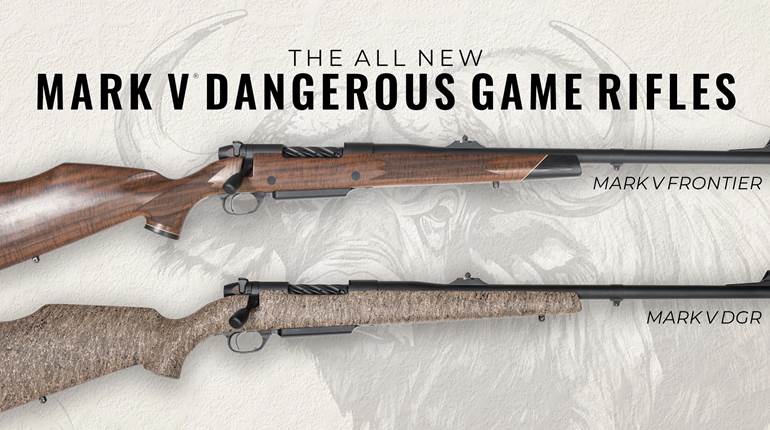

In 1905, the ’03 received an improved bayonet and sights. Rare indeed are guns in .30-’03 with the 1905 improvements made before the .30-’06 cartridge was adopted. All arms and accoutrements from the author’s collection. Photos by Smith Photographic Services, Shreveport, LA.

Roosevelt’s comments were duly passed down to Chief of Ordnance Gen. William Crozier, who immediately ordered Springfield and Rock Island to cease production until the bayonet issue could be addressed. Crozier convened an Ordnance Department committee to evaluate the various types of bayonets and to make recommendations as to which type should be adopted to replace the unsatisfactory rod bayonet. The committee settled on a conventional knife bayonet similar to the Model of 1892 used with the ’03’s predecessor, the .30-40 Krag. It was determined that the new bayonet should have a 16" blade in order to compensate for the reduced length of the ’03 rifle as compared to the longer Krag. On April 3, 1905, the “Bayonet, Model of 1905” was adopted. The new bayonet was placed into production at both Springfield Armory and Rock Island Arsenal.

The Ordnance Department took advantage of this production halt to reevaluate the rifle’s sights because there had been some criticism of the original design. It developed an improved folding-leaf rear sight with better windage and elevation adjustment capability. In addition, the configuration of the front sight was changed to a more simplified design. The new sight was adopted and given the “Model of 1905” designation. The leaf of the new sight was graduated to 2,400 yards on the face with a small notch at the top of the slide for the 2,500-yard increment. The “battle range” (with leaf in the folded position) was 441 yards.

Upon incorporation of the 1905 changes—stock, handguard and sights—production resumed on the M1903 rifle at Springfield Armory in November 1905. Rock Island Arsenal did not begin assembling any of the modified rifles until after April 1906. Barrels initially made after the incorporation of the M1905 modifications were stamped with the year of production (“05”), the initials of the manufacturer (i.e., “SA”) and the Ordnance Department’s flaming bomb insignia. Subsequent barrels were marked with both the month and year of production. Many of the original rod bayonet stocks were modified to the 1905 configuration, and a new-pattern handguard with a high hump to help protect the rear sight was adopted. The new-pattern stock was designated as the “Type S.”

These modifications resulted in a noticeably different configuration of the rifle, although the original Model of 1903 designation was not changed. The newly redesigned rifle was still chambered for the .30-’03 cartridge. The rod-bayonet-pattern rifles were to be converted to 1905 specifications as soon as practicable. Unissued rod-bayonet rifles were ordered to be modified to the new pattern, and the relative few that had been shipped to U.S. Army units were recalled for conversion.

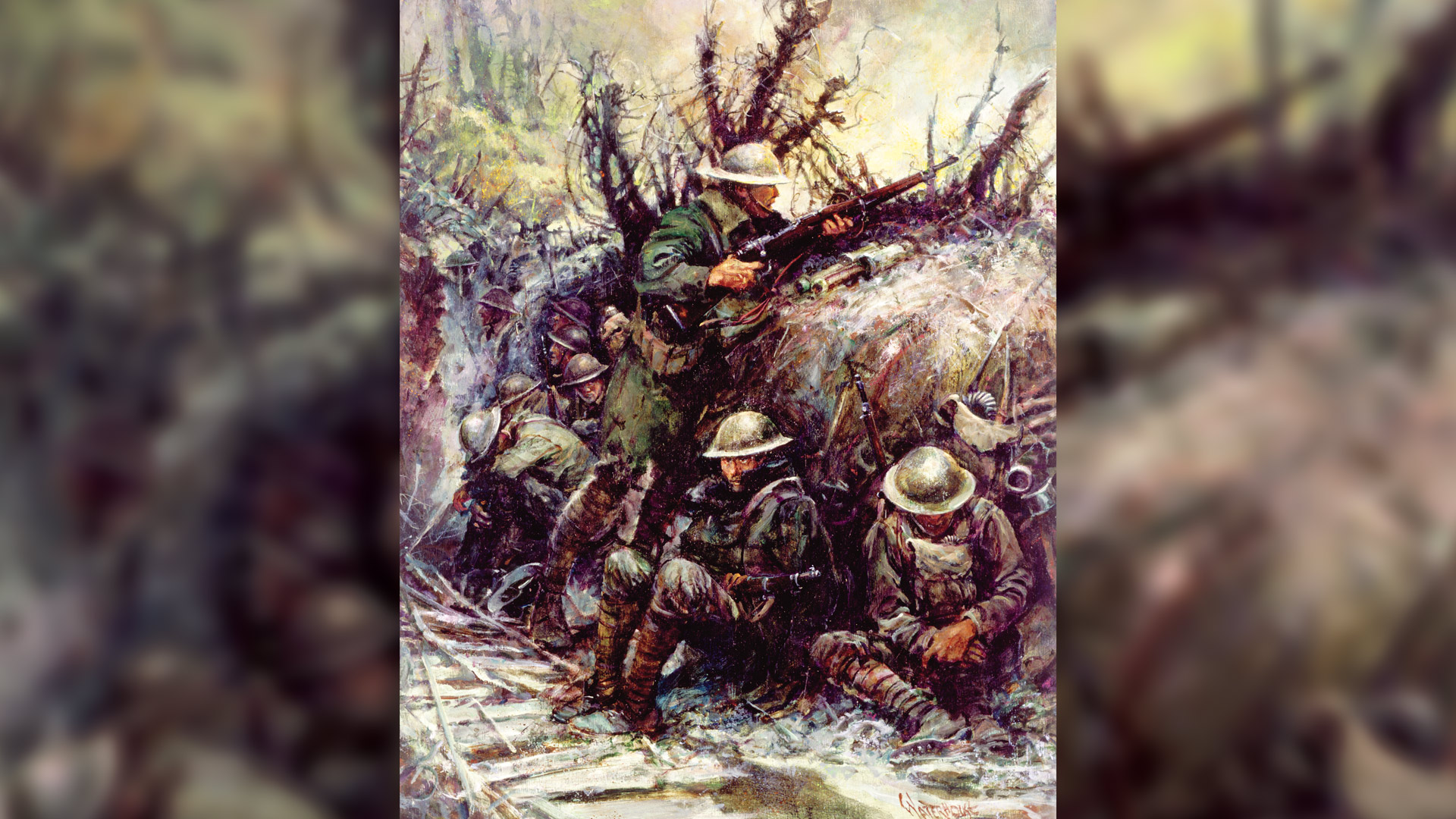

The “rod-bayonet” M1903 was singled out for scorn by no less than President Theodore Roosevelt himself. It was changed to a conventional blade bayonet, similar to that of the Krag, in 1905.

Even as Springfield and Rock Island were laboring to get the newly redesigned M1903 rifle back into production, manufacture was again halted. Ongoing testing and evaluation had determined that the sharp-nosed spitzer bullet recently adopted by Germany offered significant ballistic advantages over the round-nosed M1903 (.30-’03) cartridge. Advances in the formulation of a less-erosive smokeless powder contributed greatly to a much longer bore life as compared to the original .30-’03 cartridge. These advantages were too great to overlook, so production of the M1903 rifle remained suspended pending evaluation of the new cartridge.

In October 1906, a new cartridge incorporating the spitzer bullet and improved powder was approved for adoption by the secretary of war as the “Cartridge, Ball, Caliber .30, Model of 1906.” The leaf of the rear sight for the new cartridge was graduated to 2,800 yards. (rather than the 2,400 for the .30-’03) and the battle range was now 547 yards. The .30-’06 was born.

Soon after adoption of the .30-’06 Sprg. cartridge (.30 caliber, adopted in 1906), the manufacturing tooling was changed to accommodate the new cartridge. Many of the existing .30-’03 barrels were modified to .30-’06. Due to the slightly shorter dimensions of the new round, it was necessary to rechamber the barrel, which resulted in the length being reduced by 0.200". It was also necessary to shorten the stocks and handguards by 0.200".

The increased range provided by the spitzer bullet of the .30-’06 required changes to the M1903’s sights. Those of the .30-’03 (top) were calibrated to 2,400 yards, while those of the .30-’06 were extended to 2,800 yards.

Virtually all of the .30-’03 M1903 rifles were modified to .30-’06 specifications, except for a small number that somehow escaped conversion. A few of the rod-bayonet rifles had been presented to various dignitaries, including some state governors, and thus, were not converted. A handful of the .30-’03 rifles in the rod-bayonet and 1905 configuration were “unofficially” removed from the system and remain intact today.

Any unmodified original M1903 rifle still chambered for the .30-’03 round is a very rare, valuable and desirable collectible. An example modified for the M1905 specifications but still in .30-03 caliber is actually more rare than an original rod-bayonet rifle, although the latter will typically bring more on the collector market.

The 17" sword bayonet we know as the M1905 (above) was the result of their efforts. This .30-’03 barrel (below) was made at Springfield Armory in 1905.

There have been a few cases where an unmodified .30-’03 M1903/1905 rifle went unrecognized as it was assumed to be the much more common example converted to .30-’06. The only discernible external dimensional difference is the slightly greater length of the unmodified .30-’03 example as compared to the same rifle modified to .30-’06. While still desirable collectibles, M1903 rifles with ’05-dated barrels chambered for the .30-’06 round are infinitely more common—and significantly less valuable—than examples remaining in their original .30-’03 chambering. A potential purchaser must be very careful, as there are many “restored” examples around today, some purported to be the “real thing.”

The sights of the original M1903 (above) were soon replaced by the 1905 model that offered better windage and elevation adjustments.

Another way to ascertain if a rifle is still chambered for the .30-’03 round is to note that the bolt will not fully close on a .30-’03 cartridge in a .30-’06 length chamber. However, the reverse is not true as a .30-’06 cartridge will chamber in a .30-’03 rifle. There have been a few examples where a .30-’06 chamber has been opened up a bit by a “restorer” to permit a .30-’03 cartridge to be chambered in order to dupe a buyer into believing that the rifle in question was an original, unmodified .30-’03 example. This reinforces the advice to observe the overall length of the rifle, as compared to a .30-’06 rifle an original .30-’03 example will be 0.200" longer.

Some of the M1903 rifles chambered for the .30-’03 cartridge remained in use for a period of time until sufficient numbers of .30-’06 ’03s were available for widespread issuance. The older .30-’03 rifles were recalled for modification to the new cartridge, and by 1909, the U.S. military was essentially fully equipped with .30-’06 M1903 rifles. With the change to the .30-’06 cartridge and the previous alterations to 1905 specifications, the M1903 rifle was in the basic configuration that would see production at varying levels for the next four decades.

As compared to the .30-’06 cartridge, very few commercial rifles chambered for the .30-’03 were produced, primarily due to the cartridge’s short tenure of service to the U.S. military. Winchester Repeating Arms Co. introduced a .30-’03 version of its lever-action Model 1895 rifle in October 1905, but it was never a big seller. Just 2½ years later, in March 1908, the .30-’06 version of the Winchester M1895 lever-action went into production, and it soon proved to be one of the best-selling variants of the rifle. Myriad other commercial rifles chambered for the .30-’06 cartridge have been produced over the past 100 years and are still very popular.

Today, the .30-’06 cartridge and the M1903 rifle are inexorably linked in the minds of most hunters, target shooters and rifle enthusiasts. It is often forgotten that, for the first 2½-plus years of the rifle’s existence, the ’03 was chambered for another cartridge that is almost always overlooked today: the .30-’03. The unquestioned superiority of the .30-’06 soon resulted in the .30-’03 being relegated to the proverbial dust bin of history—never again to be resurrected. This almost-forgotten cartridge will always be in the very large shadow of the venerable .30-’06.

Widespread dissatisfaction with the ramrod bayonet of the original M1903 forced Gen. William Crozier, the chief of ordnance, to assemble a committee charged with developing a replacement.

German Patent-Infringement Claims

While the new .30-’06 cartridge was a marked improvement over the original .30-’03 round, its adoption was not without some controversy. When the M1903 rifle was standardized, the Ordnance Department was aware that the design likely infringed on some Mauser company patents.

On March 15, 1904, Gen. Crozier contacted the Mauser firm and suggested consultation on the subject. Eventually, it was determined that the ’03 design violated five Mauser rifle patents and two clip patents. An amicable agreement was reached, and the United States agreed to pay Mauser royalties of 75 cents per rifle and 50 cents per thousand chargers (stripper clips) up to a maximum of $200,000. The final installment was paid in July 1909.

Shortly after the final payments were made to Mauser, another German firm, Deutsche Waffen-und-Munitionsfabriken, made a claim that the spitzer bullet of the M1906 cartridge was an infringement on its patents. The U.S. government replied that no patents had been violated, and the U.S. Army Ordnance Department had conducted experiments with sharp-pointed bullets at least as early as 1894. The German company disagreed and filed suit demanding a royalty of $1 per thousand cartridges (up to $250,000).

Before the suit could go to trial, World War I intervened, and the German bullet patent was seized by the American government under the Alien Custody Act. This put the issue “on hold” for the duration of the war. However, in 1921, an international tribunal found that, although the initial German claim was without merit, the United States’ seizure of the patent was a violation of existing treaties and awarded damages of $300,000.

By the time all appeals were exhausted and accrued interest assessed, the American government paid out more than $400,000 to settle the claim. It is interesting to note that the amount paid to settle an admittedly groundless claim was more than double the amount paid to satisfy the clear patent violations inherent in the M1903 rifle and its charger.