This Pattern 1853 Enfield, with the name J.A. Fallin of the 23rd Virginia carved into its stock, was picked up on the slope of Culp’s Hill on July 28, 1863, by discharged Union soldier David Starry. The Fallin rifle is shown here (top) with several other original Confederate Battle of Gettysburg artifacts from the National Park Service’s collection, including a blanket used to wrap Confederate dead after the battle.

This article was first published in American Rifleman, May 1999

In 1861, Howell Cobb of Georgia stood on the floor of the United States Senate and spoke with the full attention of all those who were present to hear him. “We can beat you Yankees, even if we are armed with cornstalks.” And with those words Senator Cobb, and the rest of the Georgia delegation in the U.S. Congress, resigned their seats and headed south to take up arms against all those who would dare to challenge Georgia’s constitutional right to secede from the Union. Despite the distinguished senator’s words, Georgia, and the young Confederacy that the state had joined, were going to need more than cornstalks to repel the Yankee armies descending upon Richmond and other key cities throughout the South.

The Confederacy was fortunate in being home to a number of U.S. armories and arsenals that yielded guns destined for the thousands of men flocking to the Stars and Bars in 1861. It was soon apparent, however, that the supplies of arsenals, state militias and personal firearms would not be enough to sustain a prolonged war against the industrial North.

Caleb Huse, a native Northerner with Southern leanings, accepted a commission from the Confederate government and became a purchasing agent with instructions to buy up all the arms in England and Europe that could be of use to the Confederacy. Huse set sail immediately to secure the finest rifle in current use anywhere in the world. He was headed for London, England, and the offices of the London Armoury Company, the makers of the Pattern 1853 Enfield Rifle.

The Pattern 1853 Enfield rifle-musket (P’53) was then the standard arm of the British Army and was a percussion ignition, .577-cal. muzzleloading rifle with five-groove rifling cut with a progressive increase in depth toward the breech. It weighed 8 lbs., 15 ozs. without the triangular socket bayonet attached. The P’53 saw service with British troops in every corner of the globe and quickly became the standard by which all other firearms were measured.

The Pattern 1853 Enfield rifle-musket (P’53) was then the standard arm of the British Army and was a percussion ignition, .577-cal. muzzleloading rifle with five-groove rifling cut with a progressive increase in depth toward the breech. It weighed 8 lbs., 15 ozs. without the triangular socket bayonet attached. The P’53 saw service with British troops in every corner of the globe and quickly became the standard by which all other firearms were measured.

Once in England, Huse found that the factories of the London Armoury Co. were engaged in fulfilling a contract for the British government and a small contract for the state of Massachusetts. Huse contracted to receive all the rifles that the London Armoury Co. could produce during the following three years once the firm’s prior commitments were satisfied. Undaunted, Huse then set out to secure the services of the Royal Small Arms Factory in Enfield and all of the small arms contractors in the London and Birmingham regions. He literally beat the North’s agents by only hours in their attempts to buy up the surplus arms in England. Purchasing agents working for the United States were ordered to buy up all the arms in England and Belgium in an effort to dry up the market that the Confederates were hoping to corner. The Northerners’ efforts were wasted: Between 1861 and 1865 some 500,000 firearms of all types were shipped to the Confederacy from Europe, and another 400,000 were shipped to the United States and to Northern state governments.

Huse’s initial efforts resulted in the purchase of 3,500 rifles from English firms during the summer of 1861. These guns were loaded on the 700-ton, iron-screw steamer Bermuda. On August 22, 1861 the Bermuda steamed from Falmouth and ran the Union blockade, arriving in Savannah, Georgia, on September 18, 1861. The majority of these P’53 rifles were Barnett marked. Only 1,200 were manufactured by the London Armoury Co. These were the first rifles to reach Confederate soil since the start of the war.

With the two main rifle factories in England busy fulfilling government contracts for the British Army, Huse was forced to turn to the smaller contractors to fulfill his needs. He turned to the rifle makers in and around the cities of London and Birmingham. It is important to note that England, the home of the industrial revolution, was not as industrially advanced as America at the time. Few factories were producing goods on what we would now call the “assembly-line” process. In fact, the assembly line process and the concept of interchangeable parts was pioneered by Eli Whitney and in use in American armories as early as 1841. By the 1860s, only the government factory at Enfield and the London Armoury Co. were using standard gauges in the production of firearms. All the other P’53s produced during this period were being fabricated by contractors and sub-contractors working on individual pieces and hand fitting the components together. So a typical firearm of this period would bear the name of one lock maker, such as Barnett, and the name of the stock maker as well as numerous other identifying marks to attribute each component to its creator.

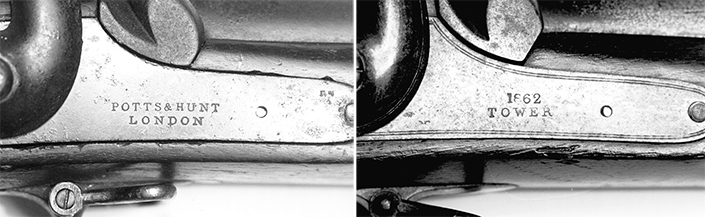

Markings

Identified Confederate P’53s have been examined with the names “King & Phillips,” “Parker Field & Son,” “Bently & Playfair,” and a host of others marked on the barrels and stocks. “Tower” often appears on the lockplates of these regionally made guns. The enigmatic “JS Anchor” is impressed on numerous Confederate P’53s, appearing on the underside of the stock immediately behind the trigger guard tang and swivel. No real explanation has yet come to light as to the significance of this marking. It is, however, safe to say that it is identified primarily with Confederate arms and equipment imported from Britain.

Firearms made for sale to non-government agencies in Britain were considered “commercial” sales. These commercial guns were not subjected to the same proof tests as those destined for British military service. The arms manufactured for the Confederacy are classified as commercial arms and do not bear the standard British military proof marks. There were no sales of surplus British martial arms to the Confederacy. It is a rule of thumb that a P’53 with a British crown and “VR”cipher and/or a viewer’s mark on the lockplate is not Confederate.

Many collectors assume that a P’53 with a “Windsor”-marked lockplate is of English origin. This is not the case. Some of the very first P’53s made were manufactured at the Robins & Lawrence factory in Windsor, Vermont. The British were looking for additional factories to produce the P’53 during the Crimean War, and the Robins & Lawrence Co. produced thousands of P’53s for British use. At the contract’s termination in 1858, the company sold the manufacturing equipment to the Royal Small Arms Factory at Enfield. A copy of the equipment was sold to the London Armoury Co. of Bermondsey. As a result, the only two British factories producing P’53s with interchangeable parts were the two factories using American-designed and produced machinery. It is not generally believed that any “Windsor” marked P’53s saw Confederate service.

Models

The designation “P’53” as it is used in this text, refers to the 1853 Pattern Rifled Musket as adopted by the British Military Ordnance Boards in 1853. Collectors commonly refer to this rifle as the .577-cal. “Three-Banded” rifle. Not unlike most military equipment, changes were necessary almost from the first issuance of the rifle. The P’53 went through four such changes before the Snyder breechloader was adopted in the late 1860s. Here is a brief summary of the four distinctive models.

P’53/1—The first model had screw-clamping barrel bands, a convex-sided backsight, a hammer with a curled tip and a button-topped ramrod with a slight swell. Dates on the locks of these first models are 1854 and 1855.

P’53/2—The second model had solid barrel bands, retained by band springs similar to those of the U.S. Model 1861 Springfield. The sides to the backsight are flat, and the ramrod may be of the first pattern or the improved pattern with a swell and cleaning jag slit head. Lockplate dates are from 1855 to 1858. Sixteen-thousand of this pattern were made in Windsor, Vermont.

P’53/3—This is the most common pattern and the one most closely associated with the American Civil War. The barrel bands are similar to the first model screw-clamp pattern. The sights are graduated to 1000 yds. instead of the previous 900-yd. graduation. The ramrod is thick, straight, and has the cleaning jag and slit head of the late model second pattern. There are also some improvements in the ramrod retention system. Most of these models bear 1858 to 1864 lockplate dates.

P’53/4—The fourth model was manufactured exclusively at the Royal Small Arms Factory Enfield and the London Armoury Co. This pattern has the Baddeley’s improved inletted screw pattern barrel bands. Very few of these P’53s ever saw service in their original form. Most were converted to Snyder breechloaders beginning in 1865. It is not generally believed that any of these rifles were sold to America during the Civil War.

Conclusion

The typical Confederate-issued P’53 is going to be a third model P’53, commercially manufactured by any number of private barrel, stock and lock makers. It will not have the crown and “VR” cipher or any martial view marks. Most lock dates will fall between 1861 and 1864. London Armoury lockplates will be marked only with 1863 and 1864 dates. These guns (L.A. Co.) did not arrive until spring of 1864. Serial numbers may be present on the barrel side, tang or stock. Additional contracts were taken out by the states of Louisiana, Georgia, Mississippi, North Carolina and South Carolina, and may be marked as such. Nearly 300,000 P’53 third model rifles are thought to have seen service in the Confederate Army.

Confederate Arms in the National Firearms Museum

Confederate Arms in the National Firearms Museum

Among the more than 2,000 firearms on display in NRA’s new state-of-the-art National Firearms Museum is an impressive collection of original Confederate Civil War arms. In the museum’s “A Nation Asunder” exhibit, there is a .36-cal. Griswold and Gunnison Navy revolver, a .36-cal. Spiller & Burr Navy revolver, several .58-cal. Richmond Armory rifle muskets, a .58-cal. Fayetteville Armory rifle, a Confederate-made .52-cal. S.C. Robinson Sharps-type carbine made in Richmond and a .58-cal. Abe Williams “Sharpshooter” rifle, among many others. In the “Arms Importation by the U.S.A. and C.S.A.” display, a host of imported arms, including a Barnett P’53 Enfield as illustrated on p. 40, are shown. A significant, and no less impressive, collection of Northern arms is also on display.

The NFM is at NRA Headquarters in Fairfax, Virginia. Admission is free and the NFM is open from 10 a.m. until 4 p.m, except for major holidays. For more information or detailed directions, write to the NFM at 11250 Waples Mill Road, Fairfax, VA 22030, or call (703) 267-1600.

Mark A. Keefe, IV