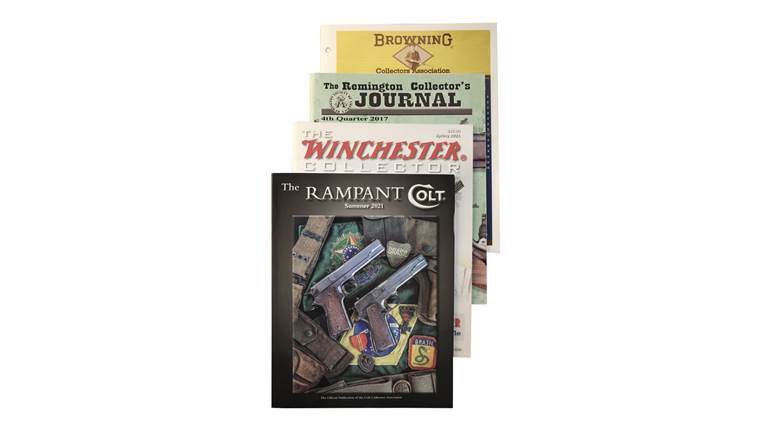

Captain Jack Starr’s mementos including his student pilot logbook, flight school class photograph from United Air Lines flight training school, a photo of Starr flying as a new co-pilot, his United Air Lines captain’s hat, his Colt Model 1908 pistol and issue holster, flight logbook, United Air Lines pilot wings and uniform lapel pin.

In the aftermath of Sept. 11, 2001, there was public demand to arm commercial airline pilots. But it was opposed by both pundits and politicians, and punctuated by one public figure who commented that airline pilots were a “bunch of cowboys.” But that opinion was based on ignorance and propelled by a political agenda rather than historical precedent. Fortunately, artifacts exist to remind us of a time when pilots were respected and depended upon to defend their aircraft. One such example is a Model 1908 Colt Pocket Hammerless pistol, formerly owned by Captain John “Jack” Elon Starr, a pilot who carried the Colt while conducting his flight duties with United Air Lines during and after World War II.

Compared with current aviation firearm protocols, the issuance and training during World War II may appear lacking. In 1942, a flight manager unceremoniously issued Captain Starr his Colt pistol with the warning, “Jack, don’t hurt yourself with it.” Issuing firearms to pilots was not simply a wartime practice, but a continuance of an established tradition that began with the first airmail pilots in the 1920s.

Pilots have been armed from the beginning of the airline industry. The demobilization of the U.S. armed forces after World War I created a surplus of aircraft and trained pilots. During that time, early aviation pioneers took advantage of affordable surplus aircraft while the U.S. Post Office Dept. (USPOD) sought a better way to expedite the mail. The U.S. government wanted faster and more dependable ways to deliver the mail, bringing about the development of new air routes.

The first airmail routes were established in 1918, and the first coast-to-coast route was inaugurated by the USPOD in 1920. Those early routes were exclusively flown by USPOD employees. Within a few years though, the government handed over the responsibility of flying the mail to commercial aviation companies.

In keeping with the long-standing tradition of protecting the U.S. mail, in February 1922, H.D. Ingalls—assistant superintendent of the Central Division of the Air Mail Service—authorized a dispatch that read: “All pilots on transcontinental flights will be furnished with side-arms for the purpose of protecting the mail.” Which “side-arms” were not specified.

Pilots flying the transcontinental airmail did so in open-cockpit biplanes over wild territory with limited navigational aids. If it became necessary to land at some remote place before reaching one of the refueling landing strips, the pilot was the sole protector of the mail. The U.S. mail was important for citizens and commerce, carrying not only letters and documents, but also currency and payrolls.

American commercial aviation, as we know it today, began with the establishment of the airmail routes in 1926. It was a result of the Air Mail Act of 1925 (Kelly Act), which forced the USPOD to use commercial operators. Several new air carriers were formed to bid on the newly created “Contract Air Mail” (CAM) routes. Although the USPOD ceased flying the mail, it still regulated airmail rates and how the mail was carried, including the 1922 requirement that pilots be armed—a directive followed until the late 1940s. As airmail became more widely accepted, more CAM routes were established and the airmail carriers acquired larger aircraft to handle the ever increasing cargo. Seeking additional revenue, airmail carriers began selling tickets on their flights to adventurous passengers. What started with open-cockpit biplanes transformed into airlines operating multi-engine aircraft with full-service cabins.

Congress, seeking to lower the cost of airmail, enacted the Air Mail Act of 1930. The new law forced many small air carriers to merge in order to survive economically. As a result, United Aircraft & Transport Corporation (UATC) acquired four airmail carriers (Varney Air Lines, National Air Transport, Pacific Air Transport and Boeing Air Transport), adding to its conglomerate of aircraft manufacturing companies and becoming an aviation monopoly.

In February 1934, a scandal involving corruption with contract bidding was uncovered. Consequently, President Franklin D. Roosevelt cancelled all commercial contracts and assigned the Army Air Corps to fly the airmail routes. The Army pilots’ unfamiliarity with the routes, the use of aircraft not designed for cargo and the fact that they were often flying in extreme weather led to numerous accidents and deaths. As a result, airmail rates skyrocketed—accidents elevated costs—and highlighted the need for commercial competition, resulting in the Air Mail Act of 1934. This law brought about renewed bidding on CAM routes and required aviation holding companies like UATC to break up—no longer could one company produce aircraft and run an airline. As a result, in 1934, UATC and its four airlines were restructured into one airline named “United Air Lines.” The United Air Lines name was already in use years earlier by the department that oversaw these four airlines.

United Air Lines initially armed its pilots by outfitting their aircraft with handguns and ammunition in sealed packages under the pilot seats. That practice lasted through the 1930s. The number of handguns bought by United Air Lines was determined solely by fleet size. Additionally, select ground personnel were also armed—in some cases with shotguns.

The criteria that United used to select sidearms or vendors is unknown. Pages from United Air Lines Pilots’ Regulations manuals from 1936 and 1937 don’t clarify the matter. They state that a “revolver with a full clip, no bullets in the barrel, would be mounted and sealed under the left (captain) seat in the cab” (cockpit). The seal could be broken for emergencies or when making landings at places other than regular stops. Although called a revolver, it seems likely that the piece was actually a semi-automatic pistol, due to the reference of a “loaded clip.”

The Model 1908 Colt Pistol was a John Browning design developed by Colt in response to its need for a pocket pistol in .380 ACP. It was easily stored or worn and was dependable, making it an ideal choice for United. This selection, however, didn’t exclude United Air Lines from purchasing or issuing other handgun models.

Captain Starr’s Colt was purchased by United Air Lines in 1933 at the Hibbard, Spencer, Bartlett & Co. hardware store in Chicago, Ill. Other known United Air Lines-marked pistols are also Model 1908 Colts, but were purchased at Salt Lake City Hardware, Salt Lake City, Utah, from 1929 through the early 1930s. The pistols are marked with either “Property of United Air Lines” or “Property of U.A.L.” According to Colt records, the pistols were part of small deliveries, and in one case, a delivery of six pistols.

During World War II, a good portion of United’s aircraft and crews flew for the Air Transport Command—flying soldiers and supplies to Alaska and the Pacific Theater. United pilots flying these routes were issued military .38 Spl. revolvers and uniforms similar to those worn by Army officers with the exception of unique stripes and emblems. Pilots were required to wear the revolvers when flying military missions. Period photographs show pilots with what appear to be Colt Official Police or Commando revolvers.

In June 1941, Jack Starr completed his initial training at the United Air Lines-Boeing Pilot Training School located in Tracy, Calif. That prepared him for an intensive one-month training program at Boeing’s School at Oakland, Calif., prior to being qualified to fly as co-pilot on United’s B247 and DC-3 aircraft. The B247 and DC-3 were used to carry the U.S. Mail and to fly military routes. After Starr completed training, he started “flying the line,” and nine months later he qualified as captain and was issued his Colt.

A few years after the end of World War II, the U.S. Postal Dept. rescinded the order for airmail carriers to arm their pilots. That did not mean, however, that pilots could not be armed. The Federal Aviation Administration (FAA), allowed any airline to arm its pilots if an acceptable implementation plan was submitted. That was the protocol for more than 50 years—up until the 9/11 attacks. Sadly, none of the U.S. airlines wanted to arm their pilots in modern times. In United’s case, its supply of pre-war pistols was offered for sale to employees around 1947—when Jack Starr purchased his Colt.

Captain Starr had a long career at United, flying the Boeing 247, Douglas DC-3, DC-4 and DC-6, after which he transitioned to jets, flying the Boeing 720 and McDonnell Douglas DC-8, and finishing his airline career as a captain on the Boeing 747. After retiring in June 1977 from United, he continued flying as a corporate pilot for the Baltimore Colts football team.

The terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, changed the airline industry forever. In response to the attacks, the Transportation Security Administration (TSA), an agency of the U.S. Department of Homeland Security, was formed. The TSA resisted the concept of arming pilots, but was forced by Congress to create a program to train and deputize pilots as federal law enforcement officers. This was put into law in 2002 as the “Arming Pilots Against Terrorism Act.” Under the act, a pilot who volunteers and completes training is deputized as a federal flight deck officer (FFDO).

The pilots who volunteer to be an FFDO submit themselves to psychological evaluations, interviews, background checks and intensive training at a federal law enforcement training center. The cost involved in the training is partially covered by the pilots themselves. After graduation, each pilot is issued a Heckler & Koch USP Compact LEM (Law Enforcement Modification) .40 S&W pistol with holster and magazine pouch. Thousands of volunteer pilots are now armed through the program, establishing a high level of protection for our U.S.-based airlines.

Acknowledgments: Carlos Vergara, Captain Jeffrey Joel Starr, Captain H.M. Bohl, United Airlines Archives, Retired United Pilots Ass’n (RUPA).