This article, written by Patrick F. Rogers, appeared originally in the December 1984 issue of American Rifleman. To subscribe to the monthly magazine, visit NRA’s membership page.

"If events had taken their normal course, it is probable that an improved version of the .38 Military Model would be our service pistol today."

Eighty-four years ago, John Browning revolutionized the handgun world with a design so basically correct in all respects that it has never been equaled.

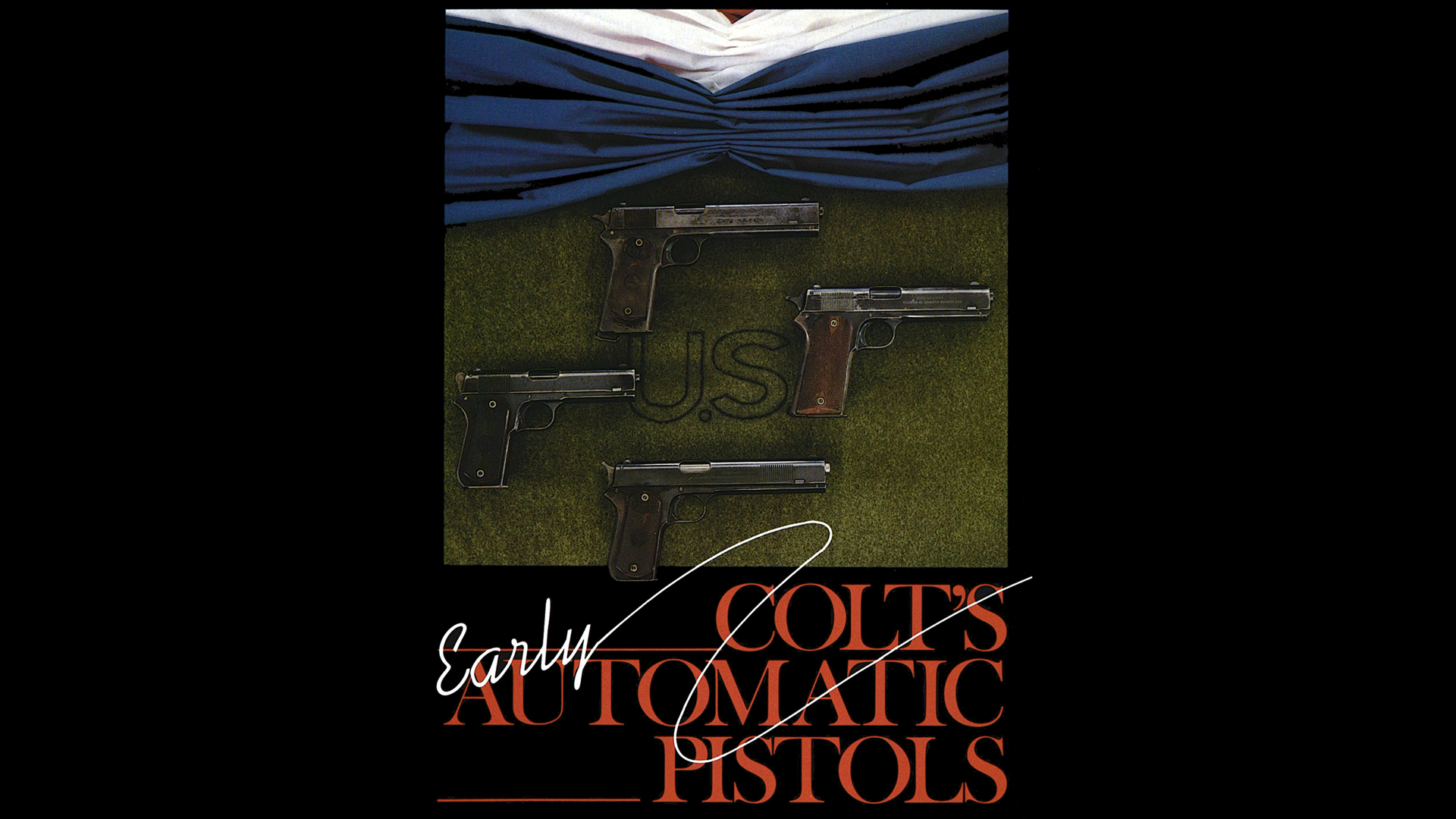

In early 1900, when Colt began production of Browning's .38 automatics, there were other automatic pistols on the market. The Mauser, Mannlicher, Luger, and Bergmann had all achieved production status. Today, all are gone, remaining only as collector's items, while developments of the basic Browning design have become the most widely used automatic pistols in the world.

No other design in the history of handguns has had equal impact since Samuel Colt developed the first practical revolver.

Browning's success came from two strengths. He possessed an inherent genius in mechanical design, and he was an enthusiastic and experienced practical shooter. This enabled him to visualize what an entirely new type of gun should be like and then design an arm to realize the concept efficiently.

In addition to being a superior gun designer, Browning was also a master gunsmith and machinist. Better than any other gun designer of the day, he knew how guns were made. He would move along a production line watching the work, picking up a tool, and demonstrating how any operation should be done.

He had the greatest respect for the men who made his guns. It was mutual. Browning's production line workers nicknamed him "the Master."

Lacking a formal education, Browning had trouble with blueprints. While working with Colt on the prototypes of his automatics, he would visualize a part, cut out the outline from drafting paper, and take it to the model shop. He would ask for a part made to match the outline and specify the thickness. His visualizations were so accurate that, with minor hand fitting, the parts could be assembled directly into the prototype pistols.

John Browning's original Colt Model 1900 was a landmark achievement in semi-auto design. Its basic concepts remain in regular use today.

John Browning's original Colt Model 1900 was a landmark achievement in semi-auto design. Its basic concepts remain in regular use today.

Browning started work on military automatic pistols in 1894. His work proceeded along two lines, resulting in successful prototypes of gas-operated and recoil-operated .38 automatics. The prototype pistols were demonstrated to Colt company officials and extensively tested from 1895 to 1898. Both designs were successful, and both were superior to existing military automatic designs.

In 1898, Colt selected the recoil-operated pistol for production. Development of the gas-operated model was dropped. It is not hard to see why. The gas-operated pistol used a toggle action actuated by a gas-driven lever. It was a fascinating design (described in detail in the June, 1975 American Rifleman), but it was inherently more complex than the recoil-operated design. It would also have been less reliable with the ammunition available in the 1890s.

The recoil-operated pistol design incorporated all the features which characterize subsequent Browning designs. The pistol was the first to use the operating slide principle. The slide, a single strong piece, enclosed the full length of the barrel and contained all operating parts with the exception of the barrel, hammer, and trigger mechanism.

The slide moved backwards and forwards on grooves machined in the frame. The barrel was attached to the frame by links and pivoted down and back to unlock. The recoil spring was located under slide moved to the rear. It then drove the slide forward, stripping a fresh cartridge from the magazine and pivoting the barrel forward and up to lock.

The first pistols combined the rear sight (arrow) with a safety lever. The feature was discarded for separate safeties and sights.

The first pistols combined the rear sight (arrow) with a safety lever. The feature was discarded for separate safeties and sights.

With the exception that post-1911 models replaced the forward link with a barrel bushing or a slide/barrel support surface, this system continues to be used in all locked-breech Browning designs to this day.

Nothing about the description sounds particularly remarkable. Most high-powered automatic pistols built today, whether Browning designs or not, incorporate some or all of these features. Browning's remarkable accomplishment was to invent these concepts and introduce them all simultaneously in one pistol design.

If the new pistol's design was remarkable in 1900, its ammunition was sensational! The .38 Automatic Colt Pistol (ACP) was the first American pistol cartridge designed to use smokeless powder. It fired a 130-gr. jacketed bullet at a velocity of 1,260 f.p.s. and a muzzle energy of 460 ft.-lbs.

The standard .38 Government revolver cartridge in use in 1900 fired a 148-gr. lead bullet at a velocity of 750 f.p.s. The .38 ACP would penetrate 11-7/8"-pine boards. The .38 service revolver cartridge would penetrate only five.

A disassembled Pocket Model shows the somewhat complicated double-link mechanism used in early Browning .38s.

A disassembled Pocket Model shows the somewhat complicated double-link mechanism used in early Browning .38s.

Only two other smokeless powder automatic pistol cartridges were available in the United States in 1900. The .38 Colt ACP outperformed both as the three cartridges were loaded at the time.

The .30 (or 7.63 mm) Mauser, introduced in Europe in 1896, fired an 85-gr. bullet at a velocity of 1,323 f.p.s. with a muzzle energy of 330 ft.-lbs. It would penetrate 11-7/8"-pine boards.

The .30 (or 7.65 mm) Luger cartridge was introduced in 1900. It was not as powerful as the .30 Mauser. The Luger cartridge fired a 93-gr. bullet at a muzzle velocity of 1,160 f.p.s. with a muzzle energy of 278 ft-lbs. It would penetrate 10-7/8"-pine boards.

The .38 Colt ACP with its larger, heavier bullet was a much more effective cartridge than either of the two German rounds. Contemporary shooters agreed with this evaluation.

The .38 automatic pistols provided shooters in 1900 with entirely new capabilities. The .38 Colt automatics were the magnums of their time. The 70% increase in muzzle velocity over the .38 revolver cartridge gave long-range accuracy and penetration never achieved before. The original load was reduced to 1200 f.p.s. before World War 1, primarily to improve accuracy. It also reduced nominal chamber pressure from 35,000 to 28,000 p.s.i. which tended to prolong barrel life. In the late 1930s, muzzle velocity was reduced again to 1,100 f.p.s. Penetration dropped to nine 7/8"-pine boards.

The new .38 automatic was a radical step forward. The shooting public was interested but not wildly enthusiastic. Colt sold 3,500 of the new Model 1900 automatics in the first two years of production. While commercial sales were important, Colt's main goal was to sell to the Armed Forces, and the Army was definitely interested. The service pistol played a far more important part in the battle tactics of 1900 than it does today. It was particularly important to the cavalry and the artillery.

Cavalry units were expected to make mounted charges against enemy units. The cavalryman's carbine could not be used effectively when he was mounted. The sword and the pistol were the weapons used in the charge. American officers, with the combat experience of the Civil War and the Indian Wars behind them, knew that the pistol was the most important weapon. They considered it the principal offensive weapon of the U.S. cavalry.

Browning may have gotten the idea for his recoil operating principle from the action of a parallel rule. The double links of the pistol act in the same way as the connecting links of the rule. As the barrel recoils, it drops out of engagement with the moving slide.

Browning may have gotten the idea for his recoil operating principle from the action of a parallel rule. The double links of the pistol act in the same way as the connecting links of the rule. As the barrel recoils, it drops out of engagement with the moving slide.

The artillerymen fired their cannons directly at enemy troops from positions in or very close to the front lines. Hostile cavalry charges to kill the gun crews and capture the cannon were considered to be a major threat. Artillerymen were trained to fire their cannons at an enemy cavalry charge until the hostile horsemen were at point-blank range. Then, they took cover around the guns and fired at the cavalrymen with their revolvers, the last defensive weapons of the artillery.

A successful automatic pistol appeared to offer three significant advantages. First, it would hold more rounds, eight to 10 ready shots compared to the revolver's six. Second, if properly designed, it could be rapidly reloaded with spare magazines. This allowed sustained rapid-fire without the long pauses required to reload revolvers. Third, it offered a far faster aimed rate of fire under combat conditions. This resulted from the self-cocking action of the automatic, allowing rapid aimed fire without breaking the shooter's grip to cock for each shot.

The first two points seem obvious. The third seems strange today. We are accustomed to the idea that a double-action revolver can be fired as rapidly and as accurately as an automatic. Modern practical pistol matches have demonstrated this many times. This is true with modern revolvers and skilled double-action shooters. Neither were available in the 1890s. Double-action revolvers were relatively new then. The average soldier was far from being a skilled double-action shot.

Double-action shooting was regarded as useful only in emergency situations at point-blank range. Ammunition for pistol practice was limited. Most practice firing with the revolver was done firing single-action.

Single-action firing required breaking the shooting grip to cock the hammer before each shot. The effective rate of aimed fire achieved with the revolver was low. A self-cocking automatic pistol offered the possibility of accurate, aimed rapid fire.

The military potential of the new pistol was obvious. A single specimen was tested by a U.S. Army Board of Officers between January and April 1900. The Board was favorably impressed. In its report it stated:

The test to which this pistol was subjected was in every way more severe than that to which revolvers have been heretofore subjected, and the endurance of this pistol appears to be greater than that of the service revolver. It possesses further advantage as follows:

Very simple construction.

It is easy to operate.

It is not liable to get out of order.

It is capable of a very high rate of fire.

It can be conveniently loaded with either hand.

It gives a high initial velocity and flat trajectory.

It is more accurate than a revolver.

The Board recommended that the .38 Colt automatic be considered for adoption as the service pistol and that a trial lot of pistols be purchased for field testing.

An initial Army order for a small lot of pistols was placed in the spring of 1900. A second order was placed in early 1901. The number of pistols in each lot is unknown, but Army records indicate a total of 200 Model 1900 pistols was delivered to the Army at Springfield Armory. The U.S. Navy was also interested and placed an order for a small lot of pistols late in 1900. The exact number of pistols in the Navy order is not known, but is estimated to have been less than 50.

The Military Model of 1905 in .45 cal. was designed to meet Army demands for a larger caliber after experience in the Philippines.

The Military Model of 1905 in .45 cal. was designed to meet Army demands for a larger caliber after experience in the Philippines.

Unfortunately, no records of the Army and Navy trials of the 1900 Model Colt appear to have survived. However we can deduce the probable military reaction by the modifications in design which Browning made for Colt in 1901.

Despite its many excellent design features, the 1900 Model had its faults as a military pistol. The principal problems were the combination rear sight-safety and the lack of any method of knowing when the pistol had been fired empty. Both problems required actual field service in order to become apparent. They had to be fixed if Browning's .38 automatic was to become an effective military pistol.

The pivoting rear sight-safety was effective as a mechanical device. It positively locked the firing pin when applied, but as a practical safety it was nearly useless. When the 1900 Model is held in the hand in a normal shooting grip, the safety cannot be touched by the shooting hand. It can only be activated by reaching over the slide with the free hand. This is awkward and slow.

It is possible to bring the pistol up to shoot, only to discover that the safety has been forgotten and the pistol will not fire. In 1900, when few U.S. firearms had safeties, this problem must have been common. The small size of the notch in the safety which served as the rear sight did not give a good sight picture. While usable for precise shooting under slow-fire conditions, the sight picture could not be picked up rapidly. This was a serious defect in a pistol intended for military or police use.

This was easily corrected. The pivoting rear sight safety was replaced with a fixed rear sight with a larger notch. This design was retained on all future Browning .38 automatic designs. Colt also applied the new sight design to the original 1900 Model with no other changes. The new variation was named the "Sporting Model." In 1903, a 4.5"-barreled version was produced as the "Pocket Model."

The second problem was more severe and required more extensive redesign to correct. There was no hold open or indicator device to show that the last cartridge had been fired. It was possible to fire the 1900 Model empty without realizing it.

Under the mental and physical stresses of close combat, it is easy to lose count of the number of shots fired. If the pistol lacks a method of indicating that it has been fired empty, the first warning is likely to be the dismal click of the hammer falling on an empty chamber.

Allowing the slide to run forward on an empty chamber also delays reloading. If a 1900 Model has been fired empty, reloading requires removing the empty magazine, inserting a loaded magazine, and pulling the slide to the rear and releasing it to chamber a cartridge. What was needed was a device to indicate that the pistol was empty and to facilitate reloading.

Browning's solution was simple and elegant. A sliding lever was added to the left side of the pistol frame. When the pistol was empty, the magazine follower pushed the lever upward into a notch cut in the left side of the slide, locking it to the rear. The shooter thus had an immediate visual clue that the pistol was empty.

When a loaded magazine was inserted, downward pressure on the sliding lever released the slide. The slide was immediately driven forward by the recoil spring. The slide stripped the first cartridge from the new magazine and loaded it into the chamber. The pistol was instantly reloaded, cocked, and ready to fire.

By the simple addition of one new part, minor additional machining on the slide and receiver, and a slight change in the magazine design, a major defect in the original design was corrected.

Colt incorporated this improvement in a new version of the Browning design. The new pistol was designated the Military Model and placed in production in 1902.

In addition to the slide locking and release lever, the Military Model also incorporated a lengthened grip which allowed an increase in magazine capacity from seven to eight rounds.

A lanyard ring was added to the lower left side of the grip. This looks strange to modern shooters. It was considered essential in 1902, however, when the majority of military pistol users fought mounted and a pistol dropped from a horse was lost if not secured with an lanyard.

Government interest in the Military Model was immediate. Two hundred pistols were delivered to Springfield Armory in 1902. The military future of the new pistol appeared bright. It combined a powerful and accurate cartridge with a simple and reliable mechanical design. It was superior to the .38 Colt service revolver in almost all respects.

If events had taken their normal course, it is probable that an improved version of the .38 Military Model would be our service pistol today. But outside events intervened. Browning had designed a .38 cal. automatic because that was what the Government wanted. Suddenly, this was no longer true.

In 1899, the U.S. Army became involved in heavy fighting in the Philippines. In the close-quarter infantry combat which followed, the .38 Colt service revolver repeatedly failed to stop determined attackers. In 1904, the Army established an investigating board headed by Colonels John T. Thompson and Louis A. LaGarde to investigate the failures of the service revolver and recommend changes if required.

The Thompson-LaGarde board conducted extensive tests with a wide variety of pistols and ammunition. Their final recommendation eliminated the Colt .38 Military Model as a potential service pistol. It called for the replacement of the .38 revolver with an automatic pistol or revolver of "nothing less than .45 caliber."

It was obvious that the Government would no longer consider a .38 automatic, no matter how advanced its features. It was equally clear that Browning's basic design was superior to all other contemporary pistols. Browning immediately set to work to design a .45 cal. model.

The first test guns were completed in 1904. Military reaction was immediately favorable. Browning continued to work to improve the basic .45 design. In 1905, Colt produced the .45 automatic for the civilian market as the .45 Military Model.

The familiar Model 1911 was a significant and successful evolution of the Model 1900. The basic design has withstood the years.

The familiar Model 1911 was a significant and successful evolution of the Model 1900. The basic design has withstood the years.

The Army tested the 1905 .45 Military Model in early 1907. Its impressions were basically favorable. It praised the Colt for "its certainty of action ..., flatness, compactness, neatness, and ease of carrying." However, the Board criticized the Colt as "defective in having side ejection, no automatic indication that the chamber is loaded, and no automatic safety." The Board recommended the procurement of more .45 Colt automatics for test, but only if their three deficiencies were corrected.

This recommendation resulted in the last pistol whose design derives directly from Browning's original .38.

Colt modified the 1905 .45 design by incorporating a loaded chamber indicator, extending the ejection port upward and partially over the top of the slide and relocating the ejector to obtain vertical ejection, and adding a grip safety to the frame. These modifications created a new version known to collectors as the .45 1907 Contract Type. Two hundred were manufactured and delivered to the Army for testing. Colt considered the 1907 Type to be sufficiently different from the Model 1905 to require its own serial number series running from 1 to 200.

The Model 1907 was the last of the models derived from Browning's original .38 automatic. In 1911, the U.S. Army adopted a modified version as the Model 1911. Seventy-three years later, the same basic design is still in service with the U.S. Armed Forces.

The Government's decision to adopt the .45 automatic reduced the .38 automatic's sales. Nevertheless, Colt continued to produce them until 1929. The evidence indicates that they still had a devoted following. Colt replaced the .38 automatics with the Colt .38 Super, a Model 1911 chambered for an increased power loading of the .38 automatic cartridge.

It is always interesting to see what shooters thought of an obsolete gun before it became obsolete. The .38 Colt automatics received good reviews. In the early 1930s, Gen. Hatcher compared the .38 automatic cartridge to the .45 ACP and the 9 mm Luger and wrote, "It is generally agreed that the Colt .38 automatic cartridge is the best highpowered pistol cartridge made. . . . (when) the Army put its stamp of approval on the .45 caliber it was only natural that the Colt Company should give all their attention to the new model, for it was assumed that any and all buyers of military automatics would want what the Army wanted and so the .38 automatic was left to die.

"But it would not die. The ballistics of the cartridge were too good. People found that the new Army .45 fell short at long ranges at which the old .38 still held up, and that no pistol cartridge in the world equaled the .38 automatic in penetration. So it happened that there has always been a call for that excellent shooting gun from long range pistol shooters and from people to whom deep penetration seems to be an essential feature. Thus the old .38 (automatic) continued to have a good sale in spite of the fact that its mechanical features were twenty-five years old. It was clumsy and awkward (compared to the 1911 Army automatic), its grip was at the wrong angle but how it did shoot!"

And it still will! A major part of the interest of gun collecting to me is the opportunity to test-fire the guns of previous generations and compare their performance with the guns and ammunition of today. I have test fired all the variations of the early Colt automatics and have always found them to be accurate. The .38 Sporting and Military automatics are particularly accurate. All you need is a pistol in good mechanical condition and proper ammunition. Never use .38 Super cartridges. They will chamber but are unsafe in the early .38 automatics.

We take the lowly slide stop for granted today. but it was a major innovation when Browning added it to the 1902 Military.

We take the lowly slide stop for granted today. but it was a major innovation when Browning added it to the 1902 Military.

I recently tested two .38 Military Models firing commercial .38 automatic ammunition. The test firings were done at 25 yds., using a two-handed hold with forearms supported. Both pistols delivered 2"- 3" groups consistently. The best group obtained was 2-1/4" and the worst 3-1/2".

What made these results particularly interesting to me is that they were done at the end of a series of tests of 9 mm automatics with modern ammunition.

The old Colts equaled the best performance achievable with the 9 mms and were superior to many combinations of modern 9 mm pistols and ammunition. Not bad for an 80-year-old design and pistols manufactured in 1904 and 1906!

What made the early .38 Colt automatics accurate? First, they were expensive, top-of-the-line pistols when they were manufactured. Second, they were made in times when skilled labor for hand fitting and assembly was available.

But I think there is another significant factor. By today's standards, they were "long slides:' Modern shooters trying to wring the last drop of accuracy from the current .45 automatic design often pay large amounts of money for pistols modified to include a 6" or 7" barrel and lengthened slide.

The early .38 Colts came with 6" barrels with the exception of the Pocket Model. Their slides are tightly fitted, and the distance the slide is guided by the frame during its rearward and forward motion is more than double that of the modern 1911 design. In effect, the .38s came from the factory as "long slides" with accuracy jobs.

The early Colt automatics do offer an interesting field for the collector. A basic collection could consist of a 1900 Model, a Sporting Model, a 1902 Military Model, a Pocket Model, and a .45 cal. Military Model. These five pistols would be a complete set of the early locked-breech Colts.

If a five-pistol gun collection seems small, don't worry. There is no need to stop there! The early Colt automatics display a fascinating variety of minor mechanical and marking variations. Changes in hammer styles, markings, and slide serrations have no effect on the basic design or shooting characteristics of the pistols. They do, however, create a splendid array of sub-types to fascinate collectors.

The pre-1911 pistols are easily identified. All .38 models are marked "AUTOMATIC COLT CALIBRE .38 RIMLESS SMOKELESS" on the right side of the slide. The .45 Military Model was similarly marked, with the caliber designation changed to ".45 RIMLESS SMOKELESS." Original 1900 Model .38s have smooth walnut grips except for some of the Army pistols which have roughly checkered wooden grips. The .45 Military has checkered walnut grips.

All other models have identical black hard rubber grips marked "COLT" in large letters and the Colt trademark in the center of the grip. Occasionally, factory pearl or ivory grips will appear. These have small Colt medallions inset if they were made at the factory.

Some shooters preferred the smooth walnut grips of the 1900 Model to the later black hard rubber grips. This explains the occasional Sporting Model, Military Model, or Pocket Model which turns up with "incorrect" walnut grips. Since shooters, then as now, have always been individualists, it also accounts for 1900 Model pistols with the later black rubber grips installed in place of the original walnut.

The Model 1902 Sporting pistol (left) had vertical serrations at the front of the slide, carried over from the military version. The 1902 Military (right) had the slide lock, lanyard loop and eight-round magazine. Checkering provided grip at the front.

The Model 1902 Sporting pistol (left) had vertical serrations at the front of the slide, carried over from the military version. The 1902 Military (right) had the slide lock, lanyard loop and eight-round magazine. Checkering provided grip at the front.

Another interesting feature which creates fascinating variations for collectors is the location and pattern of the slide serrations. The purpose of the serrations is clear. They provide a rough surface on the otherwise smooth slide. This allows the shooter to get a good grip when he is retracting the slide. So far, so good. However, the first three .38s, the 1900 Model, the Sporting Model, and the 1902 Military Model display an interesting series of changes in slide serration .positions during their production runs.

Early Model 1900 pistols have rear serrations consisting of 16 vertical grooves. The first lot of Model 1900s delivered to the Army had the same serration pattern. The second lot of Army pistols, delivered in late 1900, showed a distinct change.

The vertical serrations were moved to the front of the slide, approximately 1.3" to the rear of the muzzle. Commercial Model 1900s also changed to frontal slide serrations at about the same time and retained them to the end of the production run.

When the improved Sporting Model was introduced in late 1901, it retained the frontal vertical serrations. In 1906, the serrations were moved to the rear and remained there to the end of Sporting Model production in 1908.

When the .38 Military Model was introduced in 1902, it had frontal slide serrations of a new and distinct pattern. The vertical grooves used in earlier models were replaced with a sharply checkered rectangular area. This serration pattern was used only on the 1902 Militarys. In 1906, vertical groove serrations were introduced, and the serrations were moved to the rear. The vertical rear serrations were retained until production ceased in 1929.

"The pivoting rear sight-safety was effective as a mechanical device ... but as a practical device it was nearly useless."

The .38 Pocket Model and the .45 Military Models were not involved in these changes. They were introduced with vertical groove rear serrations and retained them throughout production.

That is what happened. Why it occurred is less clear. Apparently, the Army thought that a soldier could retract his pistol's slide more easily if he could grip the slide at the front rather than the rear. This seems reasonable, particularly for a cavalryman who must keep his reins in his left hand to control his horse. In theory, frontal slide serrations allow him to grip the slide with the fingers of his left hand while still holding the reins. In practice, the frontal slide serrations did not prove to be an advantage.

Colt appears to have switched from rear slide serrations to frontal because the Army requested it. When the Army lost interest, they returned to the previous rear-of- the-slide serration.

While this information will allow you to immediately identify any of the early Colt automatics, my best advice to anyone who is seriously interested is to buy books first! The best reference is Colt Automatic Pistols by Donald B. Bady. This is a specialized book, devoted entirely to Colt automatics, containing invaluable information for the collector. The general Colt reference books also have sections on the early automatic pistols which contain valuable information.

Forming a collection may be challenging. Production of all models was limited. Only 3,500 1900 Models were produced. Next in scarcity is the .45 Military Model with a total production of 6,100, followed closely by the .38 Sporting Model with approximately 7,500 produced. The .38 Military Model and the .38 Pocket Model are more common.

No matter how you look at them—as outstanding examples of John Browning's genius, an interesting phase in American firearms history, or superb material for a gun collection—the .38 Browning automatics were remarkable pistols. They are no longer in use, but the technology they introduced is marching on: a remarkable tribute to a gun designed in the 1890s by a man who died in 1927.

—Patrick F. Rogers

![Auto[47]](/media/121jogez/auto-47.jpg?anchor=center&mode=crop&width=770&height=430&rnd=134090788010670000&quality=60)