The modern era of powerful handguns began with Smith & Wesson’s 1935 introduction of the .357 Magnum. That company’s major competitor, Colt, also came along with Single Action Army (SAA) models in .357 Mag. before World War II and double-actions a few years later. In the postwar era, there was a strong surge of interest in ever-larger magnums, particularly the .44 Magnum. Yet, for reasons I never understood, Colt did not get involved, preferring instead to promote its racy Python in .357 Mag. Finally, in the early ‘90s, Colt introduced the first version of its biggest “snake gun”: the .44 Mag.-chambered Anaconda.

At that time, I wrote several stories about the Anaconda in both .44 Mag., as well as the slightly later .45 Colt version, and found it to be an exciting, innovative platform. Since the Anaconda was facing strong competition from several similar revolvers from S&W and Ruger, there was lots of shooter interest. And while it is true that sales of the .44 Mag. cartridge was a major factor in spurring sales of .44 Spl. ammunition, there were still significant numbers of guns and ammunition sold in the more powerful chambering for outdoorsmen who saw the need for it.

Of course, well before the magnum era, Colt’s Mfg. Co. had enjoyed a unique position in American history. Even before the Civil War, the Yankee firm had developed and produced a decisive new firearm platform that heralded considerable importance. In that broad conflict, revolver-armed cavalry fought many battles at close range. The wheelgun was king in such a setting, and Colt made the best to be had. Its 1860 Army Model was the standard in both power and accuracy. Never afraid to use plenty of steel to make powerful handguns, Colt continued to dominate the handgun field through the remainder of the 19th century. Most of that was due to the legendary Single Action Army revolver, usually made in .45 caliber. At the turn of the 20th century, revolvers became more refined, with the wide use of double-action/single-action trigger systems and swing-out cylinders for faster loading. Colt’s big gun at that time was the New Service, made until 1941 when World War II saw the self-loading handgun become the preferred battlefield personal arm.

Half a century later, Colt’s first-issue Anaconda seemed not to sell well against the N-frame S&W Model 29 and the Ruger Redhawk, but cost may have been a factor. That first Anaconda was an accurate gun with lockwork that was new, as opposed to a basic design of pre-20th century origins. When the first Python ceased general production in 1999 and the last of the original Anacondas expired several years later, the old-line firm was left with no modern revolver. Fortunately, dynamic new leadership came along in the form of Paul Spitale, Colt’s executive vice president of commercial business. An avid outdoorsman, he saw a market for high-quality revolvers and set about making them again—particularly for those who couldn’t live without the Colt pony trademark.

Colt’s recent release of a new and improved Anaconda reveals yet another entrant into the revised snake-gun series that is, in every sense of the word, better than its earlier effort. New Anacondas are top-of-the-line revolvers for Colt, and they receive as much human attention in the manufacturing process as is possible in this age of robotic gunmaking. Still, it is properly programmed machines that do much of the work, permitting Colt to sell the new Anaconda at about $1,500. That is no small accomplishment in today’s financial climate. So, how did Colt do it?

The pattern was provided by the newest Python. There was much grumbling from shooters about the departure of the original Python, a wonderful old revolver that could no longer be produced and sold at a profit. But, in 2020, Colt introduced a new version that had all the contours and class of the original Python with inner workings that lent themselves to modern manufacturing. The result was a gun that equaled anything Colt had ever done. The new .357 Magnum was a milestone gun and richly deserved the Python designation. It has sold quite well, but Colt knew that if the company were to regain any part of the big-revolver market, it would need a big-magnum platform. It only made perfect sense to not replicate the original Anaconda design but rather to borrow features from the successful Python re-design.

So the new Anaconda is, for all intents and purposes, a slightly enlarged version of the new Python. It is a big gun, available initially in both 6" and 8" barrel lengths with the latter measuring more than a foot long and weighing more than 3 lbs. And while the lockwork design replicates that of the new Python—with the action based on a leaf-style mainspring rather than the original Anaconda’s coil mainspring—the new gun’s internal components are scaled to handle the somewhat larger cartridges. Of course its frame, too, is upsized for strength, as the .44 Mag. cartridge is a test for any gun.

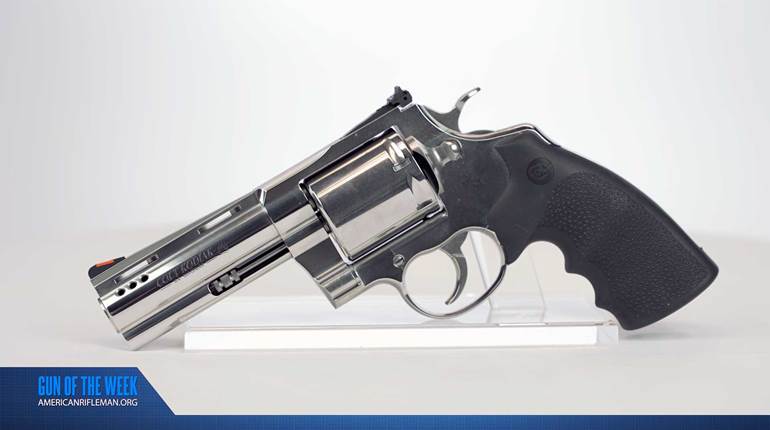

My first impression upon unboxing the new Anaconda was of its visually appealing finish. Shipped in a molded plastic hard case, the stainless-steel six-shot’s exterior has a surface that is just a little less shiny than the nickel plating of days past. If anything, it provides an impetus to pick up the gun. Combine that with one of the most appealing contours in gun design, and this revolver has the handsome look of a true classic. A racy, ventilated rib was a first on the original Python, and it is a prominent feature on the new Anaconda as well. So is the pugnacious, squared-off underlug on the straight-profile barrel. Familiar curves on the cylinder latch and a double curve to the trigger guard complete a package that, to me, says, “This is what a revolver should look like.”

While the deliberate use of a classic form is an appeal to shooters who admired older models, it is not all there is to the new Anaconda. This is as modern a revolver as can be found—after all, it is a .44 Mag., and that’s a serious level of power. Adding strength to the Anaconda is a topstrap that measures 0.370" thick all the way across the cylinder opening. Also, the cylinder, at a tiny fraction under 2", is among the longest Colt has ever made. Compare that to the 2020 Python, which was beefed up for use with modern .357 Mag. ammunition; its cylinder is about 1.5" long. In my opinion, the rugged nature of the Anaconda spells not only performance, but longevity.

The Anaconda exhibits a number of touches that should be perceived as valuable to enthusiasts. The sights are excellent. At the front is the ever-present red ramp, but, glory be, it’s removable—just turn out a set screw in its front face. I expect that Colt will offer a kit with various types (and heights) of inserts. At the other end of the sighting plane is a new rear sight design that is fully adjustable for windage and elevation. I was impressed by the positive nature of its adjustment clicks, its heavy-duty appearance and that it is all-black. That’s right, there’s no white outline. In addition, the topstrap is drilled and tapped for a 12-slot, black-anodized aluminum Picatinny base, albeit one that requires removal of the rear sight, accommodating rings or clamp-on bases for pistol scopes or red-dots, respectively, if that suits your fancy.

One of the most pleasing contours on the new Anaconda design is the grip frame, which can be fitted with the checkered wood panels of either the original or revised Python. Spitale notes that the original Anaconda’s stocks were “too beefy for some hands” and that the new gun’s stocks are slimmer on the exterior. But Colt has chosen yet another, arguably more practical, option for the new gun as well, and my shooting samples were fitted with it: a one-piece pebbled rubber Monogrip from Hogue. It attaches by way of a single screw at its base to a stirrup affixed to a crosspin that runs through a hole in the revolver’s frame. Its rubber material is firm, and I don’t believe there’s as much of a cushioning effect as might be expected. But after a respectably lengthy range session, I am convinced that the Monogrip solidly anchors the revolver in the shooter’s hand.

The new Anaconda introduction was pretty important for Colt, and a number of reviews on paper and online praise its trigger action. I agree, and I attribute the improved trigger feel to the gun’s refined lockwork. Not only is the leaf-spring system more smooth and consistent, the action components and engagement surfaces are manufactured to much tighter tolerances than were possible in the older, hand-tuned guns. Spitale describes the new design’s trigger feel as more “linear,” yielding better double- and single-action experiences.

The new Anaconda introduction was pretty important for Colt, and a number of reviews on paper and online praise its trigger action. I agree, and I attribute the improved trigger feel to the gun’s refined lockwork. Not only is the leaf-spring system more smooth and consistent, the action components and engagement surfaces are manufactured to much tighter tolerances than were possible in the older, hand-tuned guns. Spitale describes the new design’s trigger feel as more “linear,” yielding better double- and single-action experiences.

The new gun’s components are noticeably beefier than those found in older models and are well-polished and free of tooling marks. The mainspring stands out as being particularly robust. Also, there’s a separate cylinder-stop mechanism, which resides above and just forward of the trigger, similar in design to those found in Smith & Wesson’s line of revolvers.

While the mechanism offers both double- and single-action functionality, my guess is that the single-action mode is likely to see greater use. At the range, when making a deliberate shot, there is a much greater likelihood of success when thumb-cocking the hammer, so as to take advantage of the light, crisp 4-lb. pull. When the target is close and things are happening quickly, it’s more likely to be a long-arc, double-action pull of 11 lbs. Shooters who seek mastery of the DA/SA revolver often use a double-action pull that stops just short of firing, then finish with a quick touch to release it. It’s called “staging” the trigger.

In preparing for my range time with the new Anaconda, I worked with the trigger system a great deal. Having fired virtually every maker’s revolvers extensively, I wanted to be very familiar with the Anaconda. My impression was that its trigger is unique; it was not particularly light, but it was extraordinarily smooth. It can be staged quite easily, but I still contend that most all shots in the field will be using the single-action mode, so that is how I fired the gun for accuracy.

Because of ammunition constraints, I was unable to do as much of the subjective, informal shooting that usually accompanies these reviews. The gun was fired with three different loads from Winchester, Remington and Speer, and the results are tabulated nearby. Its operation was functionally flawless, and its accuracy, firing handheld from benched sandbags, was excellent. When fired with the 4X 28 mm Leupold FX-II Handgun scope, the 8" Anaconda managed 50-yard groups averaging 2.78"—nearly equivalent to the 25-yard groups shot with the same gun using irons.

In the past few years, Colt has nearly rebuilt its revolver catalog with modern and up-to-date models. At its peak, the company catalogued seven so-called “snake” guns (see p. 26). Four of those are now back in production: the Cobra, King Cobra, Python and, now, the Anaconda. We might see some of the others sometime down the road, and I would venture to guess that the Diamondback would be a good choice, particularly in the rimfire chamberings. Bringing out such a small-caliber “snake” would make a fine bookend for what is now certainly one of the finest large-frame revolvers in the world— the new .44 Mag. Colt Anaconda.