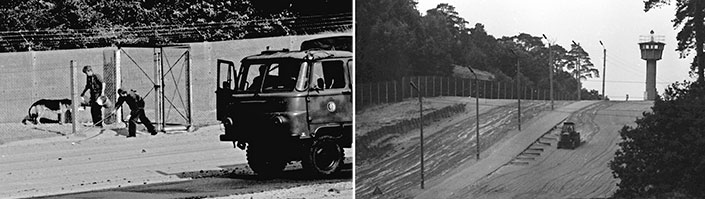

Two men huddled in the bush on the West Berlin side of the notorious “Anti-Fascist Protection Wall.” They intently scanned the East German Border Guard tower opposite them, about 50 meters across the so-called “Death Strip.” The strip was not mined—it was just a wide open area of carefully manicured sand that was covered by the guards’ machine guns, mostly the East German version of the Soviet AKM assault rifle, the MPi-KM.

Under the tower, a wire mesh kennel housed several East German working dogs. The dogs provided early warning of any intrusion into the border area and were the object of interest for the two men. One of the two men pulled an odd weapon out of his coat pocket—a heavy-duty slingshot. He loaded a smooth pebble into the sling and whispered, “Ready?” The other man put down his East German Zeiss Jena 10X 50 mm binoculars and pulled his own weapon out, a suppressed High Standard H-D Military in .22 caliber. Just in case the guards decide to get out of hand, he thought. He quickly ensured a round was chambered and replied, “Ready.”

The sling shot sang, and the pebble flew across the strip, into the kennel, hitting one of the Alsatians. It yelped and the others began to bark. Two guards tumbled out of the tower, looking for the source of the disturbance. But they were looking into East Germany, not toward West Berlin. The Wall was meant to prevent people from getting out of the German Democratic Republic, not into it.

An East German military truck came rumbling down the access road and stopped in front of the tower. Three more guards jumped out and, for a moment, there was confusion as everyone tried to figure out what had happened.

The observers clicked off their stop watch—five minutes had elapsed. It was a good test. The guns and sling shot went back inside their coats when it was clear they were no longer needed. They waited until it was calm before they slipped out of their hide, through the forest, and back into the city. In their civilian clothes, they looked no different than any other West Berliners, except they weren’t. They were Americans.

They were armed and prepared for any eventuality, part of a clandestine U.S. Army Special Forces unit stationed in West Berlin beginning in 1956. The unit was sent to Berlin when the Commander of the U.S. Army in Europe realized having six Special Forces “A-Teams” deep inside communist East Germany would be an ace in the hole should the Cold War turn hot. In reality, it was a “Hail Mary” plan—a means to quickly infiltrate the teams directly into enemy territory to wreak havoc behind the lines. They would help to slow down a Soviet advance by sabotaging the all-important railway connections around Berlin, report intelligence on the enemy, and raise guerrilla forces to fight the communists inside and outside Berlin. A formidable and—some would say—suicidal task for the men chosen to serve there.

It was pure unconventional warfare, much like the Office of Strategic Services of World War II, except they were already trained and working in their potential operational area as an underground organization. The unit, known to the outside world only as Detachment ‘A’ Berlin, was referred to as “Special Forces Berlin” in the Army’s secret war plans. Besides the senior officers of the Berlin Brigade and U.S. European Command, few were aware that a Special Forces unit existed in Berlin.

Some 800 men served there, from 1956 until 1990, when the unit closed down after the Iron Curtain and the Berlin Wall fell in 1989. On constant alert with a two-hour “string,” the 90 men that made up the unit at any one time walked the streets of Berlin planning how they would survive if the balloon went up. Six 11-man teams, each with their own mission and target, speaking the language and capable of disguising themselves as a German worker or an East German soldier, carried whatever arms or tools of the trade were needed for the task. Few of the tools were U.S.-issued.

In 1956, when the first men arrived in Berlin from the Bavarian town of Bad Tölz, where they had been members of the 10th Special Forces Group, they carried standard U.S. infantry arms: the M2 carbine, the M3 submachine gun and the M1911A1 pistol. Those were quickly replaced by the Walther P38 pistol and the Walther Maschinenpistole Kurz (MPK) submachine gun, both in 9 mm Luger. The MPK came with a 10"-long suppressor that could be quickly attached in place of the barrel end nut. Both were chosen for their chambering and because they were German. The P38 was in use on both sides of the Wall and was reliable within its limits. It had a single-stack, eight-round magazine like that of the seven-round .45 ACP M1911A1, but not its knock-down power. That said, 9 mm Luger ammunition would be more readily available during wartime. Dynamit Nobel 125-gr. full metal jacket (FMJ) ammunition was used with both guns, not only because of the constraints of the Hague Convention, but to ensure proper feeding of the rounds during semi-automatic and full-automatic fire. A standard load was six magazines for each gun, in practice, however, many more were carried.

Several other submachine guns were considered and tested before the Walther was adopted, but it was the MPK that could stand up to abuse and still operate even if it had been immersed in mud for several days (after the barrel was cleared, of course). The MPK fired from an open bolt, but it remained stable and accurate out to 50 meters, firing single shots or in short bursts, good for most urban combat situations. It was also easily concealed in the ubiquitous leather briefcase that each German used to carry his lunch to work.

But there were other requirements to consider and other weapons were often needed. The “silenced” .22 High Standard H-D Military was one, and each team had several for those situations when rapid, quiet fire was required, like taking out a guard. Even more specialized was the Mark I/II Hand Firing Device, a single-shot, silenced pistol that looked very much like a tool out of a plumber’s work bag that had been developed by the British Special Operations Executive (SOE) during World War II. Called the “Welrod,” it was chambered to fire either the .32 ACP or 9 mm Luger. At least 14,000 unmarked Welrods were built, and many were dropped to resistance fighters in Europe before the end of the war.

Both were used by Special Forces during Vietnam, but it was widely assumed they went out of service in the late 1960s. They didn’t. Special Forces Berlin had stocks of both, and either the H-D Military or the 9 mm Welrod were carried for assignments where it might be necessary to quietly dispatch enemy personnel.

Another was the Military Armaments Corporation “Stinger,” a single-shot, .22-cal. survival gun that was issued in a metallic tube that could be disguised as a hair creme or toothpaste dispenser. It was accurate and lethal only if it was held directly against the target. When tested at the range, it was found the bullet would begin tumbling within feet of leaving the Stinger’s short barrel.

Berlin was nicknamed the “Outpost of Freedom” by the forces of the United States, the United Kingdom and France. It lies 110 kilometers east of the West German border in the heart of Prussia. Around 12,000 Allied troops were stationed in West Berlin, which was divided into three sectors with the French in the northwest, the British in the central west and the Americans in the southwest. The Soviets occupied the eastern sector known as East Berlin. The difference was that while only several thousand Russian troops were in the East sector, the city of Berlin was surrounded by over 1 million Warsaw Pact troops. If you included the Polish and Czechoslovakian armies, it was many more.

Many thought West Berlin would become the world’s largest prisoner of war camp when and if a war started. But the men of Special Forces Berlin planned to make the Warsaw Pact’s mission most difficult. The unit trained to operate clandestinely inside the city, knowing that it would be necessary to go underground at a moment’s notice prior to hostilities. In addition to mastery of combat arms skills, each man had to know how to live as a German and how to be part of an underground organization. Intelligence tradecraft was as important to survival as shooting an enemy soldier.

Anticipating that it could be difficult to get to their assigned arms at the unit’s headquarters, euphemistically named “mission support sites” were established throughout the area of operations. These were caches of containers which held arms and equipment necessary for sustained operations. The sites consisted of four containers that were sealed and buried underground in hidden locations. Each container was packed with untraceable guns such as the British 9 mm Sten submachine gun and the Walther P38. Along with communications, demolitions and medical gear, there was enough equipment for each team to carry out its mission and, hopefully, continue to equip itself through battlefield recovery.

From its beginnings, Special Forces Berlin gained a reputation for unusual capabilities. Before the Wall was erected in August 1961, the U.S. Commander of Berlin (USCOB), Maj. Gen. Ralph M. Osborne, tasked the unit to conduct a vulnerability assessment of Berlin’s Mayor Willy Brandt. Brandt was a bit of a firebrand, and Osborne was concerned the communists might try to kidnap or assassinate him—as they had already done to several other West Berliners.

Several men were chosen for the task, and, over the course of several weeks, they developed four simple scenarios to “eliminate” Brandt. One of the scenarios was to approach Brandt’s official car as he made his habitual stop to buy a paper in the morning. “Gerhard,” the sergeant who devised the attack, demonstrated how he could remove the grip from a silenced Welrod pistol, hide it a rolled up newspaper and shoot Brandt at close range. Another plan involved a sniper rifle and a long-range shot across a pond behind the mayor’s residence.

When the USCOB was shown the assessment with its devious, but feasible plans, Brandt’s schedule and travel arrangements were quickly changed. With that, the unit began to routinely be tasked with conducting “red team” vulnerability assessments and providing VIP security in times of high threat. Unlike the military police or conventional soldiers, the men of SF Berlin had an innate ability to blend into the crowd to accomplish their jobs without being noticed.

During the Vietnam War, the unit, along with the rest of the U.S. Army in Europe, was severely strained by manpower requirements for the Southeast Asia conflict. Despite that, it had to maintain its war-fighting skills for the possibility of a war with the Warsaw Pact. In the early 1970s, terrorism became a threat to U.S. forces in Europe. Student radicals who opposed the United States’ involvement in Vietnam, as well as its presence in Germany, began to target American servicemen. The spectacular failure of the German hostage rescue at the 1972 Munich Olympics, as well as its success with the Lufthansa hijacking at Mogadishu, led the U.S. commander in Europe to task Special Forces Berlin with yet another mission: counterterrorism.

Using the equipment it had on hand and leveraging relationships with the Federal Bureau of Investigation, the British Special Air Service (SAS) and GSG 9—the new German Border Guard counterterrorism unit—SF Berlin organized and trained itself to take on the mission. The precepts were simple: study terrorist operations, anticipate threats and learn how to defeat them. The unit’s history with vulnerability assessments, VIP protection, urban combat and intelligence operations served it well. By 1977, it was considered ready for counterterrorism operations—long before any other U.S. military unit.

The unit’s Walther MPK submachine gun and P38 pistol were the primary “close quarters battle” guns. But, it quickly became evident that the P38 was not up to the task. After several thousand rounds were put through them, malfunctions increased and frames began to crack. The 9 mm Walther P5 was chosen to replace it—although many of the soldier-operators would have preferred the Browning P35 High Power because of its higher magazine capacity. Officially, the MPK and P5 were the standard arms, but many found room in their load-out bags for their personal arms. Colonel Stan Olchovik, the unit commander, and Sgt./Maj. Jeff Raker, the senior enlisted man, never batted an eye. Their unit was unconventional, after all.

The ammunition load changed with the new mission. For practice, the teams often used Dynamit Nobel plastic training ammunition that fired a non-lethal, plastic bullet. The bullet marked targets but was limited in range and would not penetrate walls. That said, it was still dangerous and would wound if one was unlucky enough to be struck by an errant round.

Another round was adopted for operations: Geco, a Dynamit Nobel’s subsidiary, manufactured a 9 mm Luger, 96-gr. round with a blue plastic tip that ensured good feeding in self-loading arms. After the round exited the barrel, the plastic tip fell away, turning the bullet into a hollow point. Again, because of the Hague Convention, these rounds were exclusively for counterterrorism operations.

Close quarters battle, or CQB, was a key component of counterterrorism training, and it necessitated a different “operator” mindset. The term and the training was a variant of that taught by the British SAS, which offered a holistic approach to training that had one aim—to guarantee success in killing.

The SAS, in their usual straightforward manner, outlined it as follows: “CQB is much more a personal affair than ordinary combat. It is just not good enough to temporarily put your opponent out of action so he can live to fight another day. He must be quickly and definitively killed so that you can switch your whole attention on the next target. Besides obvious physical abilities, the CQB operator must be cool-headed and, above all, remorseless. The pistol and the SMG [submachine gun] are the main weapons used by the CQB operator. These weapons are generally regarded by the ignorant as ‘dangerous’ and ‘useless’. In the hands of a trained CQB operator these weapons are extremely lethal. However, for the CQB operator to maintain a high degree of professionalism he must train continuously in an aggressive manner. The end product … must be automatic and instantaneous killing.”

Each member of the unit was trained intensively in CQB, and put thousands of rounds downrange under all possible conditions and circumstances. The unit’s mission and alert status required that a soldier be a precision marksman with his assigned arms—pistol, submachine gun and rifle—at all times, as there would not be time for training before a mission. By late 1977, the unit was ready for national-level counterterrorism operations. Then, on Nov. 4, 1979, the United States entered a 444-day nightmare when the U.S. Embassy in Tehran, Iran, was seized by “radical students.”

Within hours, the unit, along with other national assets from the continental United States, was alerted. The mission statement was simple, but that simplicity belied the difficulties the rescue force would undergo:

“MISSION: Joint Task Force conducts Operations to rescue U.S. personnel held hostage in the American Embassy Compound, Tehran, Iran.”

Special Forces Berlin participated in two ways. First, two unit members infiltrated Iran as businessmen and clandestinely collected the information necessary to plan and conduct the rescue. Naturally, they carried no arms, and their success was a testament to their bravery and the level of training each soldier in the unit received. A second team was tasked to rescue three American hostages being held separately in the Iranian Foreign Ministry, while the main U.S. force concentrated on the embassy compound. Berlin’s nine-man team members carried their assigned Walther P5 pistols and MPKs, as well as High Standard H-D Military silenced pistols to quietly dispatch guards at the building. Another “tool” was carried to take care of any doors that might prove difficult to open—a thermite torch “lock eater” developed by some obscure government laboratory.

When the mission was attempted, however, it came to an ignominious end after several of the Navy RH-53 helicopters chosen for the infiltration failed. The operation had to be abandoned, and only the intelligence collection team was successful in its task, unfortunately to no good end. A second attempt was readied, but it was cancelled after the hostages were released.

After the raid’s failure, Special Forces Berlin continued to prepare for its missions and operate in the divided city until 1990 when the fall of the Iron Curtain and the Berlin Wall rendered its mission unnecessary.

Or did it?

This article is adapted from the book: Special Forces Berlin: Clandestine Cold War Operations of the U.S. Army’s Elite, 1956-1990 by James Stejskal. Released by Casemate Publishers in February 2017, it is available from Amazon and Barnes & Noble booksellers.