They sung of the heroes whose valor has made us, Sole nation on earth, independent and free, And this will remain with kind heaven to aid us, In spite of invaders by land and by sea. New York, the Green Mountains, Macomb and Macdonough, The Farmer, the Soldier, the Sailor, the Gunner, Each party united have plighted their honor, To conquer or die on the banks of Champlain.

—“Verses on the Battle of Plattsburgh” by Catherine Macomb

As a nation, we often forget that there are some very practical reasons behind the Second Amendment to the United States Constitution. Not the least of these reasons is that the right to keep and bear arms and maintain a militia allows the average American citizen to defend his or her country, home and even the very concept of liberty. One of the greatest examples of this is the action of a group of teenage boys who helped defend their community of Plattsburgh, N.Y., during the British invasion of September 1814.

By September 1814, there had been multiple battles along New York’s northern border and across Lake Ontario. In early 1813, the British had invaded New York on the Niagara frontier, capturing Fort Niagara and ultimately burning the communities of Lewiston, Black Rock, Tuscarora and Buffalo. In the summer of 1814, British troops came ashore in Maryland, eventually pushing into Washington D.C., burning the Capitol and the White House and sending President Madison’s government into hiding. The British then attacked Baltimore, and the defense of that city resulted in an American victory, as well as a national anthem in “The Star-Spangled Banner.” But, no matter how dramatic, these raids on the eastern seaboard were simply a British diversion to draw American attention away from Plattsburgh, their prized target in the north, so deemed by British Secretary of War Henry Bathurst.

During the summer of 1814, the British had ended the Napoleonic threat in Europe and were quickly re-allocating battle-hardened troops to Canada with the intent of finishing off the impudent Americans. Gathered above Plattsburgh were 14,000 British troops, the largest single fighting force of the entire war. The British were ready.

Why Plattsburgh? The town sits on the northwest shore of Lake Champlain in the northeastern corner of New York State. There is a fine harbor there, and the American naval squadron (under Commodore Thomas Macdonough) was assembled on Champlain waters to resist the British naval attack. Champlain is a thin sliver of a lake, pointing like a dagger toward Albany and, ultimately, New York City. The British planned to overwhelm the defenses at Plattsburgh with superior numbers of men on land and a large flotilla on the lake. With Plattsburgh captured, the British could move on Albany, cut off Boston, lay siege to New York City and take control of Lake Ontario. The battle lines were set.

The Brave Impetuosity Of Youth

The Brave Impetuosity Of Youth

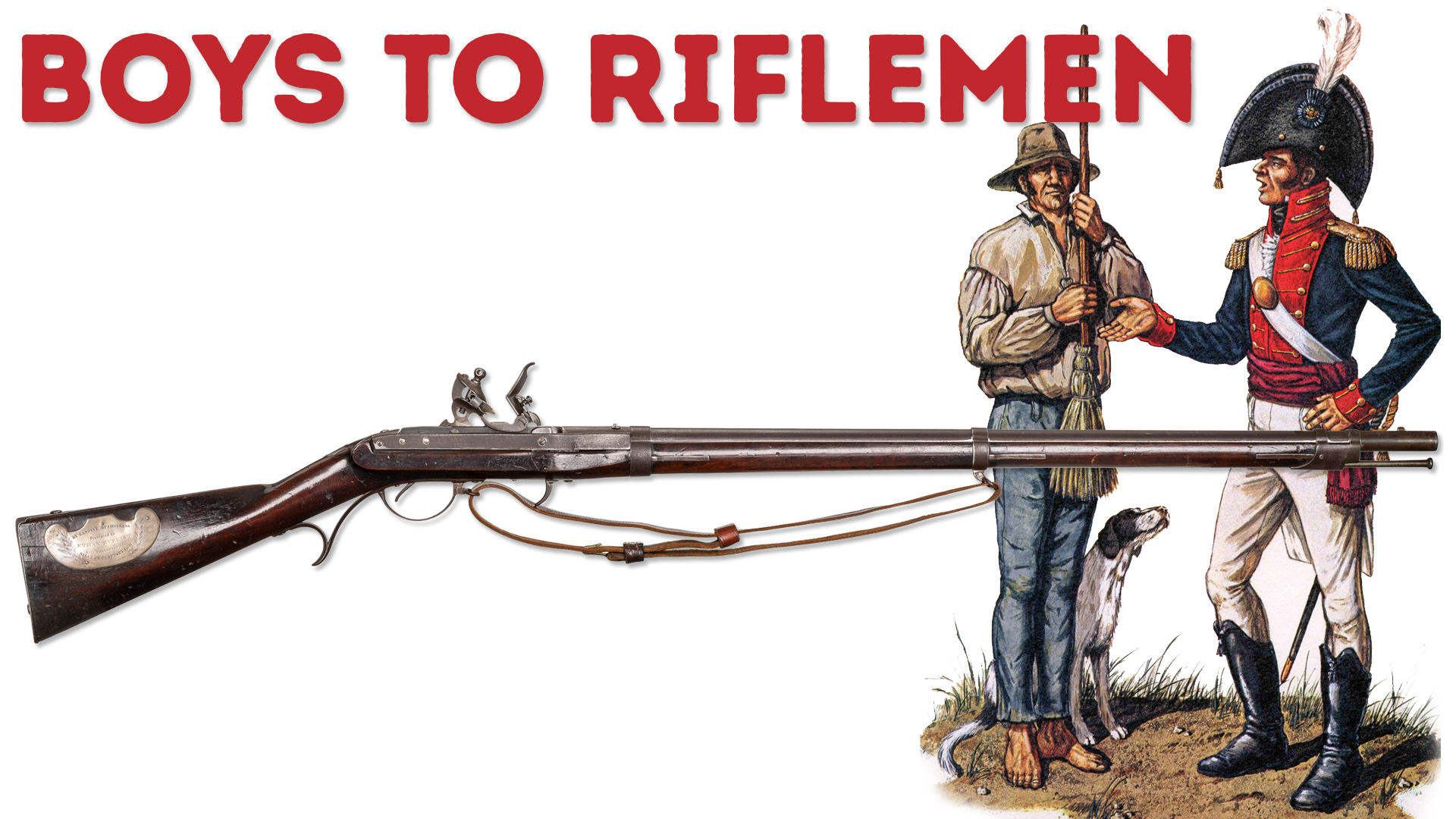

The boys of Aiken’s Volunteers were students at the Plattsburgh Academy, occupied with their school lessons and youthful games. No doubt that many of them helped supplement their family diet by hunting game in the northern woods. During the last days of August 1814, the boys watched as many of their neighbors prepared to flee the village in anticipation of the invasion. The greatest army in the world was soon to be at the doorstep of the small northern village. The British were coming.

Collectively, the boys made an important adult decision: They resolved to stay and fight. None of them was more than 16 years old, so they could not legally enlist. They approached Gen. Alexander Macomb (in overall command of American land forces), and the general, in great need of any able-bodied troops, regardless of their age, instructed the boys to find a proper military sponsor and leader. Martin Aiken of the Essex County Militia took the assignment and was made captain of the little volunteer group. Aiken was just 21 years old. His lieutenant, Azariah Flagg (of the Clinton County Militia), was 20 years old. As the boys were not “legally” enlisted, their names would not appear on any official daily muster rolls, only those kept by their officers, Aiken and Flagg. Some of the boys brought rifles from home; other longarms were scrounged for those boys who had none. Quickly the group became known as “Aiken’s Company” or “Aiken’s Volunteers.”

By September 4th, Aiken’s Volunteers had marched out to battle, with no formalized training and certainly no combat experience. By the morning of the 6th, they were in combat. Passing through some retreating militia units, the boys met the British advance guard at nearby West Chazy, and Aiken’s volunteer riflemen “gave a good account of themselves by annoying the enemy by firing from behind stumps and fences, and disputed the ground with them all the way to Plattsburgh.” While other militia units wavered along the Beekmantown Road, the boys stayed in the fight to delay the British regulars. General Macomb took notice; the boys had backbone.

The large British column continued to advance, swiftly at times, despite the harassing fire. Aiken’s boys withdrew in good order and after crossing the Saranac River, reassembled at Winchel’s Mill, which commanded the approaches of a relatively new bridge across the river in Plattsburgh. For the rest of the day, the little company of riflemen kept their fire hot against the British assembled on the far side of the Saranac River.

“No corps more useful and watchful ...”

General Macomb’s intelligence officer, Eleazer Williams (a native American who developed the “Secret Corps of Observation” using Indian scouts throughout the north country), was particularly complimentary of Aiken’s Volunteers: “There is no corps more useful and watchful than the one under the command of Captain Aikens [sic] and Lieutenant Flagg.” General Macomb apparently agreed, assigning Aiken’s boys to help the defenders of the blockhouse at Gravelly Point. Eleazer Williams later described the boy riflemen as “brave and daring in skirmishing with the enemy.” September 9th was a clear and quiet day for Aiken’s Volunteers, but also a painful one. They buried one of their own that afternoon, a boy named Peters, who had been killed the evening before.

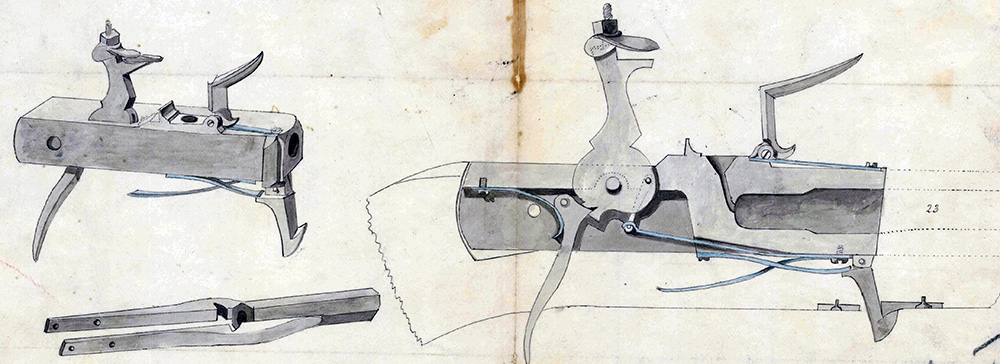

A drawing included in John Hall’s original 1811 patent for what would become the M1819 Hall Rifle illustrates how the central breechblock is configured, having a chamber, hammer, frizzen, trigger, locking lever, trigger spring, mainspring and lever spring.

Today, September 11th is a date that holds great meaning in this country due to several events. The first incidence of national significance concerning this date occurred on 9/11 of 1814. In the Plattsburgh harbor, young Commodore Macdonough delivered a stunning and complete defeat of the British naval squadron. On land, in a vain effort to force the bridgehead in Plattsburgh, the British splashed manpower in red-coated waves against American sharpshooters in their stone bastions.

In Benson J. Lossing’s Pictorial Fieldbook Of War Of 1812,” the author describes the boys’ performance at the bridgehead: “The enemies [sic] light troops endeavored during the day to force a passage of the Saranac, but were each time repulsed by the guards at the bridge, and a small company known as Aiken’s volunteers, of Plattsburgh, who were stationed in the stone mill. These young men … behaved gallantly, and they garrisoned that mill-citadel most admirably.”

A Promise From The General

The boy volunteers earned the thanks of Gen. Macomb, who praised them in his official report of the battle. Macomb claimed he “drew inspiration” from the underaged warriors within his command. At the battle’s end, the general promised each boy a U.S. Army rifle as “a reward for their gallant and meritorious conduct.”

The general’s promise of a rifle for each of the boy volunteers needed to be approved by the secretary of war, and then the appropriation required a specific act of Congress. Unfortunately, Congress did not act on this until 1822, when a joint resolution passed the House of Representatives. However, the Senate postponed the resolution, and it was not finally enacted until May 20, 1826. Fifteen years after the battle, the Army held a presentation of the rifles at Plattsburgh in 1829, where only six of Aiken’s Volunteers were available to receive their rifles. Sources vary, but apparently, most of the presentation rifles eventually found their way to the men who were to receive them.

There were 17 Model 1819 Hall breechloading rifles specifically made for Aiken’s Volunteers. Each had a semi-circular silver plaque inlet into the right side of the buttstock with the words “By Resolve of Congress” and “Presented to______ for his gallantry at The Siege of Plattsburgh.” Martin J. Aiken’s (misspelled “Aitkin” on the plaque) rifle exists today at the Clinton County, N.Y., Museum, one of the few longarms ever awarded by Congress for gallantry. The 17 young men awarded rifles were as follows:

Martin J. Aiken

Azariah C. Flagg

Ira Wood

Gustavus A. Bird

James Trowbridge

Hazen Mooers

Henry K. Averill

St. John B.L. Skinner

Frederick P. Allen

Hiram Walworth

Ethan Everest

Amos Soper

James Patten

Bartimeus Brooks

Smith Bateman

Melancthon W. Travis

Flavius Williams

Generation after generation, the myths and half-truths about the performance of the state militias during the War of 1812 have been repeated. Lazy historians cut and paste damning phrases time and again: The militia ran away. They refused to fight. They were inept and unable to effectively use their firearms. Clearly, those tales are not true, and the story of Aiken’s Volunteers proves it. There is an inherent bravery in the citizens of this nation, and the Second Amendment grants them ability to step up when the situation demands it. Would you expect any less of any other man, regardless of where he lives in this world, if his country were invaded, his home and loved ones threatened? The British army in 1814 may be viewed today as a gentlemanly foe, but, at the time, it was the dominant military force on the planet. A small group of American boys stood up to the British invasion during 1814 and did their part to keep America free.