This article was first published in the Jan/Feb 1995 American Rifleman.

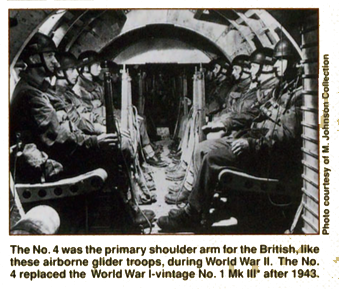

At the outbreak of World War II, the British soldier was still armed with the same rifle his father, or perhaps even his grandfather, carried. The Short, Magazine Lee-Enfield (SMLE) had, since 1902 with modifications, delivered sterling service from the mud of Flanders to the farthest reaches of the Empire. It was with this rifle that "Tommy Atkins" faced the might of Hitler's Wehrmacht in Norway, France, Belgium, North Africa and, later, Italy. The SMLE served on throughout the war, particularly in the hands of Commonwealth troops and the more neglected British formations, despite being declared obsolete in 1941.

There is no need to belittle the SMLE or No. 1 Mk III and 111*, as it was rechristened in 1926, but the British were in need of an accurate, mass-production rifle. The need was even more acute after the loss of an astronomical amount of equipment during "The Miracle of Dunkirk" in 1940.

The No. 1 Mk III, a product of the previous generation in terms of technology and production techniques, was essentially a hand-built gun. As modern mass-production methods were not available at the time of the SMLE's adoption, it contained many unnecessary frills and time consuming operations in manufacture.

Since 1929, the improved and simplified No. 1 Mk VI had been waiting in the wings, thanks to limited military appropriations and a belated rearmament program. The premise, after World War I, was to keep the more desirable features of the SMLE, while making the rifle more accurate and modernizing production techniques.

The SMLE Mark V was the first step. A rear aperture sight and a reinforcing band at the rear of the nosecap were added to solve problems experienced during World War I.

Further development continued, and in 1926 a prototype was ready for testing, the first of three patterns of the No. 1 Mk VI. Development continued, and during 1930- 31 approximately 500 were made, redesignated Rifle, No. 4 Mk I, and issued for trials to one cavalry regiment and one infantry battalion.

One may wonder why the British offered no more than lip service and a trials process to the semi-automatic rifle. It must be realized that in the '20s and early '30s, the period of development for the No. 4, no major power had officially adopted, let alone begun issuing, a semi-auto rifle on a large scale. What eventually would become the M I Garand was still on the drawing board.

As British offensive doctrine developed in the interwar years, more emphasis was placed on fire and movement, and the No. 1 priority was the development of an effective light machine gun (LMG), with perhaps a semi-auto rifle developing from it. By the time the Bren LMG was in place, it was 1935. The leadership of the period also thought soldiers armed with autoloading rifles would waste ammunition.

So the plans for and adoption of the "New Rifle" were shelved until a future emergency, which came on Sept. 1, 1939, with Germany's invasion of Poland. With a new continental war underway, the British began gearing up for the conflict, and the No. 4 Mk I was officially adopted on November 15. Thanks to interwar development, the tooling up began to produce No. 4 rifles for the needs of the by-then rapidly expanding British army.

The No. 4 Mk I retained the better features of the SMLE, but changes were made to the receiver, bolt, stock, sights, barrel, nose cap and bayonet. About the only parts remaining completely interchangeable between the No. 4 and No. 1 were the sling swivels and some buttstocks. Even the magazines, virtually indistinguishable at a glance, were not fully interchangeable due to manufacturing differences.

The 2-lb., 2 ½ -oz. SMLE barrel was replaced with a 2-lb., 9-oz. free-floating barrel in an effort to improve accuracy. The heavy and difficult-to-manufacture nosecap was discarded in favor of a milled, and later stamped, front reinforcing band and a simplified sight guard, radically changing the outline of the rifle.

This arrangement allowed the free-floating barrel to protrude from the fore-end and eliminated the precise full-length bedding required to make the SMLE accurate.

While prewar standards of finish and manufacture were typically high, utility (i.e., putting functioning rifles in the hands of the troops) became a higher priority as the war progressed.

The finishing of metal parts was one of the first "luxuries" to go. The commercial quality finish was soon dropped in favor of phosphating and black spray painting applied rather sloppily at times. The No. 4 began the war with the Mk I barrel with five-groove Enfield rifling; however, as the war progressed, barrel manufacture became a bottleneck. Several solutions were tried to speed up the desperately needed production, including two-groove and drawn steel tube barrels.

The No. 4 began the war with the Mk I barrel with five-groove Enfield rifling; however, as the war progressed, barrel manufacture became a bottleneck. Several solutions were tried to speed up the desperately needed production, including two-groove and drawn steel tube barrels.

In 1941, the two-groove barrel was tested and found to be little different in terms of accuracy and barrel wear, so it was accepted as the Mk II barrel. Barrels made from drawn steel tubes were also tested and adopted, as they sped production, but they did not hold up well under service conditions. The Mk III barrel, as these were known, was subsequently dropped. The knox form (the reinforced area where the barrel is joined to the action) was made of a separate steel tube then shrunk and pinned in place in the Mk III installation.

British service rifles previously had been stocked with naturally dried walnut, but due to anticipated wood shortages in a future war, experimentation began with kiln-dried walnut in 1935. When the No. 4 went into mass production, wood shortages were more acute than had been perceived and kiln-dried birch and beech were approved for rifle stocks as well.

Warping caused the wood to bind on the sear and trigger on these stocks, a problem not fully addressed until the introduction of the Mk 2 in 1949. Experiments were also conducted with all-metal and bakelite stocks, but accuracy was difficult to maintain, and the project scrapped.

The buttstock itself was made to four different lengths, often marked at the top of the stock: "B" for bantam; "S" for small; "N" for normal; and "L" for long.

A simplified spike bayonet was introduced for the No. 4, replacing the 17" Pattern 1907 sword bayonet. The sword bayonet was found to be almost useless as a fighting knife or for brush clearing and had proved unwieldy in bayonet fighting.

Contemporary studies indicated all but 6" of the bayonet was unused in combat. When weighed together with economy and ease of manufacture, the spike bayonet was adopted, being at first a cruciform shape, the Mk 1, then switching to the simpler Mk II rounded spike design. An even cruder and therefore less expensive Mk III was later introduced.

The spike was fitted directly to the barrel and retained by lugs on the left and right side about 2" down from the muzzle. The weight of the bayonet affected the bullet impact point, and seldom were rifles zeroed with the bayonet in place at the factory.

The receiver itself was strengthened band squared off, requiring less milling and simplifying manufacture. A simple one-piece charger bridge that accepted the five round stripper clips was fitted into grooves on the top of the receiver. This replaced the rounded bridge of earlier models.

The aperture rear sights of the No. 1 Mk V were incorporated into the Mk VI and, later, the No. 4 Mk I. Since 1909, the British National Rifle Ass'n had allowed aperture sights on Lee-Enfield rifles in target matches and even lobbied in favor of them on service rifles (some suspect that this was due the sound thrashing received from the American team in the 1908 Olympics).

To the novice's eye it would appear that the No. 4 rifle had two basic types of sights, when in reality there were four. The Mk I micrometer backsight was made of milled steel with a battle sight set for 300 yds. When flipped up, it was adjustable for elevation out to 1300 yds.

The wartime-economy Mk II backsight was a simple stamped two-setting aperture sight that flipped for settings at 300 and 600 yds., much like the model first used on the U.S. M1 Carbine. The Mks III and IV were also made from stampings, but like the Mk I, had provisions for sighting from 300 to 1300 yds. The elevation adjustment was another stamped piece, retained by a spring catch.

The production of the No. 4 rifle during the war is interesting in that no preexisting small arms factories were used to make the rifles. Two new government factories were set up to produce the rifle, Royal Ordnance Factory (ROF) Fazakerley in Lancashire and ROF Maltby in Yorkshire. Birmingham Small Arms (BSA) Gun, a private company, also established BSA Shirley in Birmingham to turn out the No. 4.

Despite its role in developing the No. 1 Mk VI, RSAF Enfield did not produce any of the 2 million-plus No. 4 Mk Is made in England during the war. It concentrated on the vitally needed Bren light machine gun (LMG), its components and the No. 2 Mk I, I* and I** revolvers.

The first production No. 4s actually rolled out of ROF Maltby in June 1941, from ROF Fazakerlev in July and, in the following month, BSA Shirley began. Outside contractors produced many of the No. 4's components and delivered them to the small arms factories for assembling complete rifles.

With the urgent need for rifles pressing upon Britain early in the war, His Majesty's Government looked across the Atlantic for other sources for the new rifles. They found the assistance they required in two places, Savage/Stevens Arms Corp. in Chicopee Falls, Massachusetts, and at Small Arms, Ltd., in Long Branch, Ontario, Canada.

In early 1941, with America still officially neutral in the growing conflict that became World War II, the British contracted with Savage to build 200,000 No. 4s at the former J. Stevens Arms Co. factory in Chicopee Falls.

After the U.S. entry into the war, Savage continued to make the No. 4 under the auspices of "lend-lease" agreements with our new allies. The lend-lease Savage-made rifles were marked "U.S. Property," usually also bearing a large "S" or an "S" within a rectangular box and a "C," for Chicopee Falls, within the serial number. Overall production amounted to 1,236,706 rifles by the war's end. North American production grew to more than 2 million rifles, with some sent to China, also under lend-lease agreements.

Long Branch, located near Toronto, produced 910,730 No. 4 Mk I and I* rifles. The Canadian-made rifles were marked "Long Branch" on the left side of the receiver and included an "L" in the serial number. Wartime North American production actually exceeded British production.

The No.4 Mk I* was not actually adopted until 1946, despite being produced at Canadian and American factories as early as 1941. The Mk I* was virtually identical to the Mk I except for simplifications in design and manufacture. The principal variation was in the method of bolt release. The bolt ribway had a new slot cut for the bolt head to be pivoted upward, out of the ribway. The machining at the rear of the ribway, the bolthead catch, spring and plate, were then no longer necessary. For ease of bolt removal and manufacturing, the Mk II charger bridge was also incorporated. The only other changes were to the sear pin length, which was increased, and replacement of the magazine-catch screw with a pin.

As they had in 1914, the outset of WW I, the British found themselves at war without a proper sniping rifle in WW II, except for the venerable No. 3 or Pattern 14 Mk I (T) left over from the earlier conflict. The "T" or "TR" marking found on these arms indicated that they were fitted for telescopic sighting. This continued with the development of two further variations, the No. 4 Mk 1(T) and I*(T).

Production rifles were selected for their exceptional accuracy, being able to place seven out of seven shots in a 5" circle at 200 yds. They were then stocked and precisely fitted with two metal pads on the left-hand side, soldered and screwed to mount the bracket for the No. 32 Mk I and later scope marks. Originally designed for the Bren light machine gun, the No. 32 proved to be a rugged scope and, when combined with the sturdy mount, held up remarkably well to service conditions.

The No. 32 scopes were matched and serial numbered to individual rifles and were not to be switched. The use of kiln-dried stocks and other economy measures were forbidden on the No. 4(T)s.

The conversions to sniper rifles were initially carried out at RSAF Enfield using prewar No. 4 troop trials rifles and a small quantity of Savage/Stevens Mk Is. When supplies of these were exhausted, rifles were taken from BSA Shirley, as they were found to be the most accurate of the production guns.

Reworking rifles to be No. 4 Mk I(T)s was done first at Enfield to about 1,400 rifles, then the famous firm of Holland & Holland and, eventually BSA Shirley, produced a sniping trainer itself. H&H became the leading supplier of finished No. 4(T) rifles, producing some 26,000 between 1943 and 1945. To supplement British production, Long Branch produced a mixture of about 1,000 Mk 1(T), Mk I*(T) and C No. 4 Mk I*(T) rifles as well.

Most recently, the so-called "Last of the Lee-Enfields" have been making a prominent appearance on the surplus market. Since 1986, when the importation of surplus military rifles began anew, the World War II-vintage No. 4 has been brought in by the hundreds of thousands. While the No. 4(T)s and the trials models are difficult to obtain, and high in price when eventually found, the "New Rifle" has much to offer the shooter, history buff and beginning collector of today.