This article originally appeared in American Rifleman, January 1969.

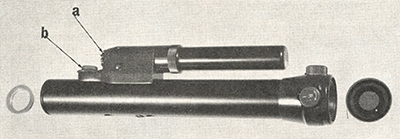

Oxford's rifle and pistol sight is unusual. It is an optical sight, but it is not a scope. There is no magnification of the image.

Within the black-anodized aluminum sight tube there is a tiny bulb which is powered by a pair of AA size penlight batteries housed in a separate tube above the sight body. When a button at the rear of the black baked enamel die cast zinc housing is pushed from left to right, the bulb lights. But because it is shielded at the rear, the bulb itself is not seen in the sight.

The shooter sees a reflection of the bulb from the rear surface of a single one-X lens at the front of the sight. By a pair of uncovered conventional click-stopped adjustment knobs at the front of the sight, the lens is tilted to move the spot of light from the bulb up and down or from side to side across the visible field to sight-in the rifle or pistol on which the sight is mounted.

Both a focus and a brightness adjustment are provided. The first is adjusted only once when setting up the sight for use, so that only a spot of light is seen and not the elongated image of the bulb filament. The illumination adjustment brightens or dims the bulb for best contrast against a dimly or brightly lit target, and to minimize “bloom” of the spot of light to apparently larger size. This adjustment is made any time to suit shooting conditions.

The only cover to the front and rear of the sight tube is a pair of snap-in plastic caps. The front cap is a neutral gray filter. Either or both may be removed for better target visibility under some light conditions, without changing the functioning of the sight.

The working principle is this: The bulb is positioned at the focus of the rear surface of the lens. Light rays striking this surface are partially reflected back to the eye of the shooter. All rays from the same point of the bulb are reflected parallel, and because the aperture for the special little bulb is so tiny the total rays are effectively parallel. Optically, then the bulb's image is at infinity. The front lens surface is complementary to the rear to produce unit magnification, permitting two-eyed target finding which aids fast aiming.

Rays of light from the target that pass through the lens emerge parallel to their original paths. So what is seen through the sight is of the same size as seen from the same position with the eye alone.

On the field of vision '”floats” the spot of light, showing with clear contrast against the target. The sighting spot is visible in light so poor that conventional metallic sights can not be defined. Because it is optically at infinity, the sighting spot is in focus to the shooter who is looking at the target image.

Consequently, the problem of trying to see in clear focus both a front sight and a rear sight as well as the target, as with iron sights, is not present. This is a commendable and unusual approach to overcoming a sighting hindrance that is particularly vexatious to those over 30 years of age as they tend to become more and more farsighted.

Also, since the Oxford sight is not a telescope, it has infinite eye relief and the exit aperture is the whole clear diameter of the eyepiece. There is no parallax.

The Oxford sight is in no way related to the military Starlight sight, which is a light amplifying system.

No means of attaching this sight to a rifle or pistol are made by its manufacturer. Consequently, to test the sight furnished the American Rifleman Technical Staff on a handgun, it was necessary to employ mounts of other makes. One inch Redfield split rings with mounting feet for tip-off .22 receiver grooves were chosen. These fit either accessory tip-off scope mount bases that attach to a rifle or handgun, or other special bases. For recoil test, a Bushnell grip-replacing mount for an M1911 cal. .45 ACP pistol was fitted to a custom accurized handgun in the Technical Staff’s test collection. Even though the space between the 2 mount rings on the scope is quite close, this was adequate for test purposes.

Several hundred rounds of both match wadcutter and full power ammunition were fired. Recoil had no noticeable effect on the sight. Shooting accuracy was equivalent to what a skilled pistol shot could achieve with the regular target sights on the pistol.

The shooters who did this part of the test shooting remarked that the sight and the mount spoiled the good balance for which, in part, the M1911 pistol is famed. Achieving a steady hold on the target was more difficult than without the scope. Recovery of sighting after firing a shot in timed- and rapid-fire was complicated by twist of the gun in the hand.

Sighting, however, was much eased by the Oxford sight in comparison with open target sights. The uncomplicated, easily seen, and single-plane-focus sight picture made accurate shooting much easier. Because of its simplicity, it suggested that a beginning pistol shooter might be able to hit his mark regularly more quickly with the Oxford sight than with conventional sights once he got used to the jiggle of the spot of light over the target. This is indeed upsetting until the shooter recognizes that the perfect sight-target relationship is a fleeting one, and learns to squeeze the trigger when the sight is approximately centered in the bull and with the same technique he must employ for good shooting with conventional sights.

To conclude the shooting tests, the Oxford sight was fitted with Weaver mount rings and bases to a 20" barreled Model 700 Remington center-fire rifle. This is a light, handy rifle for quick shots at moving game. Hence, it is appropriate to the purpose of the sight.

In initial tests from bench, grouping capability was about 2 minutes of angle. This is certainly adequate for game shooting and, considering that the spot of light displaces 4 minutes of angle, it is thought to be excellent accuracy potential.

But it was during quick sighting and shooting that the remarkable property of this sight was best appreciated. It makes the rifle on which mounted very fast to get on target, and the pip of light hangs on the target with apparently greater steadiness than possible with a magnifying scope or with open iron sights.

Shooting as fast as possible from a normal low-gun field carrying position, every shot would have made a hit in the chest area of a deer-size game animal at normal shooting range. This could have been equalled with other sights, but the tester felt that more time would be consumed by an average hunter to do so.

Other than its alteration to the balance and recovery in quick firing of a pistol, the sight was liked by those who tried it. But it was liked more by some than by others in use, and this seems to be an area for individual user decision after trial. It is interesting that the more experienced shooters of this group were the more impressed and less skeptical.

Manufactured by: The Oxford Corp., 100 Benbro Dr., Buffalo, N.Y. 14225

Specifications OXFORD LIGHTNING ILLUMINATED GUNSIGHT

Type: Optical battery powered, internal spot of light sight

Actual Magnification: IX

Field Of View At 100 Yds.: 20 ft.*

Eye Relief: Infinite

Body Tube Diameter: 1”

Objective Tube Diameter: 1.3”

Eyepiece Tube Diameter: 1”

Length: 8 ¼ “

Weight: 10 ozs. with batteries

Value of Click Or Graduation: .54 minute of angle

Price: $49.95 without batteries

* There is no true field of view as with a scope. This is the segment of total field of vision of the eyes bracketed by the sight.