This article was first published in the July 1945 issue of American Rifleman

By Leo Stoutsenberger, USAAFR

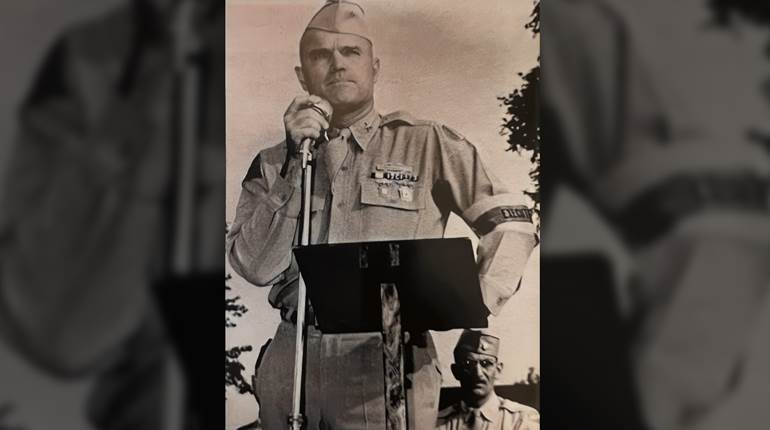

About the Cover: The image pictures a waistgunner in a Liberator bomber. An official USAF photo, taken by Karl Gaston, with Strategic Air Force in England. Made with a 4x5 Speed Graphic (5"-focus Ektra lens), setting F.8, at eight feet, open flash, on Kodachrome Daylight. Camera was set on tripod, lens open, with two synchronized flashbulbs, one on camera shooting in, one at upper left.

When the events of this war become masses of type on the countless pages of history, the work of the aerial gunner should occupy an important place in the chapter devoted to the great Allied Air Offensive. The most casual observer of present-day military operations knows the long-range bomber is primarily a weapon of attack—a lethal weapon designed to deliver destructive blows at energy installations on the ground. But the very nature of the bombing plane makes it highly vulnerable to attack. The great distances traveled by Liberators and Fortresses to targets deep within alien territory make it impossible to cover their sorties with fighter escort. So the job of protecting the big bombers falls to the aerial gunner who lives and fights within the ship's steel body. The gunner is a flying bodyguard—as integral a part of the crew as the pilot, the navigator, and the bombardier.

Someday, perhaps, whatever remains of Marshal Goering's once-vaunted Luftwaffe will grudgingly admit that the rapid decline of the Nazi's Air Arm during 1944 can be attributed in large measure to the intensive training and the resulting deadly accuracy of the young American riflemen who crouched behind their single or twin .50's in the turrets and at the open waist ports of Uncle Sam's bombers.

My job as an aerial photographer-gunner is to record graphically the effects of our strikes and the effects of the enemy's counterpunches—and to take over a gun in emergencies. In this light, then, I feel I can speak in a more or less detached way of the fiber of these marksmen who pit their wits and specialized shooting skill against the best fighter pilots the Germans send out to intercept us.

My job as an aerial photographer-gunner is to record graphically the effects of our strikes and the effects of the enemy's counterpunches—and to take over a gun in emergencies. In this light, then, I feel I can speak in a more or less detached way of the fiber of these marksmen who pit their wits and specialized shooting skill against the best fighter pilots the Germans send out to intercept us.

And when I say specialized shooting skill, I mean just that. Because if a man can't shoot after the training he gets in our Air Force gunnery schools, he simply lacks the eyesight, physical co-ordination, or whatever it takes to be a shooter—and if he lacks that, he doesn't end up as a gunner.

Preliminary training is with the rifle. Most Air Gunnery schools start their work with the .22's—work up from those to the .30 calibers. We got dry firing first; then hundreds of rounds of range firing, at fixed and moving targets. Next comes a very thorough and intensive course in aerial gunnery, firing at first from, a truck with regular skeet guns. The truck rolls along at fifteen miles per hour and each man fires thirty-two shots at clay pigeons hurled from the trap shacks. If he's good, he'll hit twenty-five out of thirty-two. Even while the gunner is overseas flying his regular combat missions, he must keep in practice and when he isn't flying he works out in the turrets which the bomb group sets "Up for that purpose in the building called the bomb training building.In this building are also Link trainers and bomb trainers for the pilots and bombardiers.

Then there is actual firing in the air for air gunnery timing at the cotton-covered wire tow sheet called the sleeve. The sleeve is usually ten feet by three feet and is towed by another airplane. The gunner's hits are scored by having the bullets first dipped in colored lithographic ink. Each gunner has his own color inkand so each gunner's hits are easilyidentified. A good gunner will getfifty hits out of 200 shots at the sleeve. All hits are circled in black as they are scored and the targets are then used over and over again.

Even though slated early in my training period to be a photographer, I had to go through the "firing mill" as intensively as the others. For months we burned up so much powder I began to be afraid there wouldn't be enough for the boys who were really slugging it out at high altitudes with the Krauts. But before many more weeks had passed, I had a close-up look at the whys and wherefores of that relentless grind of pounding away day after day at clay pigeons, towed sleeves, and rolling dummy fighters. Then I thanked God for the tough gunnery sergeant who made us do it "over and over again 'til you get it right!"

Of my fifty combat missions, thirty-seven were under vicious attack by Nazi fighters, but one mission in particular stands out in my memory. We were raiding the Markersdorf Aerodrom near Vienna. We were within a minute or two of starting our bombing run on the target, when a mixed squadron of FW 190's and 200's roared in on us out of a heavy cloud bank. They came in very fast-and if the Luftwaffe was running short of experienced pilots, it must have been in some other theater of operations because they struck from the nearest thing to a blind spot a Liberator has, and they were plenty good! They winged over as they flashed by and poured a stream of incendiaries from their 200 mm.'s which raked us from “greenhouse" to “privy.”

My first impulse was to become violently sick. For a few moments I was completely gripped by fear, almost to a point of being paralyzed. Fortunately, this initial stage passes, alongwith a gallon of perspiration, and the average airman seems to become calmly deliberate, functioning mechanically. It was then that I began to observe my buddies' reactions to the intense nerve strain and the fury of the enemy's fire.

Many things were happening indescribably fast. The Jerries seemed to be attached to spokes, whirling madly around us with our ship the hub. As they flashed past our waist windows, Tom and Blinky blazed away at them. Tom was a good gunner; he shot by the rule book. Blinky was a cunning hunter; he used some pages from the book and stuck in some paragraphs his rifle-and-shotgun-shootin' Oklahoma pappy had made him learn. He led two of those "supermen" in and let them "walk into his fire." Blinky didn't believe in throwing a lot of lead; his technique was to put one solid burst where it would do the most good--or harm, depending on which way you saw it.

He didn't do a fancy hemstitching job on the wings or bodies of either of his "pigeons." He merely removed the plastic cowling—and, incidentally, the pilot's head-from Number One fighter, and knocked the prop and most of the engine off Number Two. It was enough, in both cases. After that, Old Man Newton's law of gravity did the rest.

The noise of a fast and furious air attack is something which cannot possibly be put into words; but through it all you are conscious of many other sensations—the vibration from the four straining motors; the violent pitching and lurching of the ship as she takes direct hits; the pungent smell of burned powder. Over all this is an almost overwhelming feeling of utter helplessness and despair.

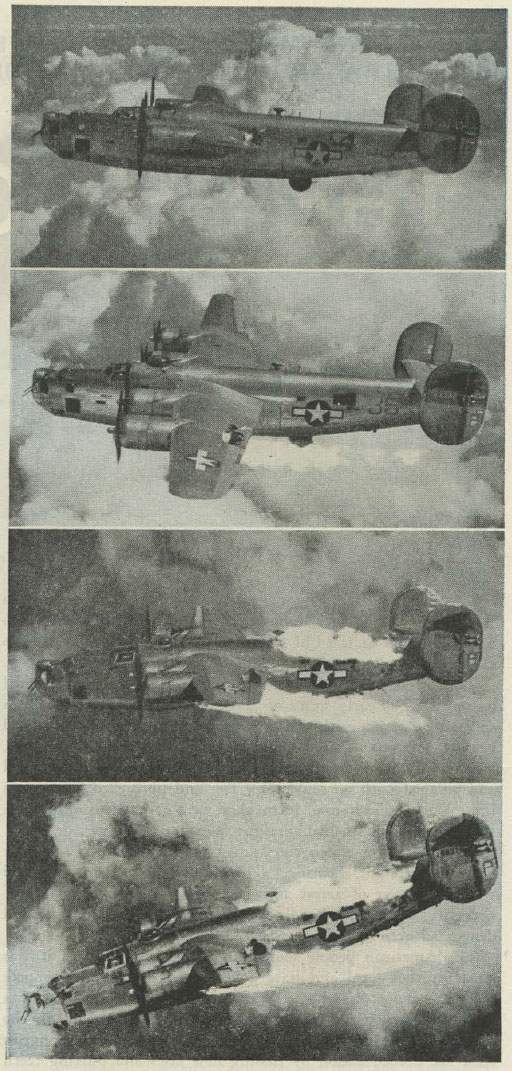

When this attack started, I was lucky enough to' be at the right waist window with my K20 camera cocked and ready. The interphones became fairly jammed as gunners from every position on the ship called out the fighters as they swept in on us. Our Number Two ship, flying on our right wing in the formation, was the first one I saw hit. At the first sight of fire coming from the plane, I started taking pictures. It made me feel like I was doing something terribly wrong, watching my buddies dying and coldly photographing them, not being able to be of any help. But that was one of the things I was there to do ....

Our own gunners were filling the air with lead. The plane on our right was completely engulfed in flames and it burned just as a piece of tin foil or celluloid would burn. I watched it plummet earthward and then I jumped to the left waist window. The ship on our left wing had been badly hit, too. Smoke was gushing from its Number Two engine and the crew members were already scrambling to the waist windows and escape hatches. I could see them jumping, and soon the air was filled with little white blotches which were the parachutes of those who were lucky enough to get clear. As the chutes whirled by us, we could see the figures of the men swinging like pendulums, unable to control the big silk canopies in the swirling currents of air that surrounded them.

Like a summer thunderstorm, the battle ended suddenly. We looked around us and counted our losses and found we werethe only remaining ship of our flight. Our pilot had to "throwon the coal" to our already overworked engines and try to catch up with the rest our formation. We had borne the brunt of the enemy's defensive action, and we had suffered. The only satisfaction we had for our losses was in the knowledge that Flights Three and Four, soon to follow, shouldn't have too many Jerry fighters swarming down on them before they could unload their eggs, for the Jerries, too, had paid a heavy toll. Before our lost bombers fell, their gunners—some of whom had hit the silk to what we hoped would be safety, and some of whom we'd never see again-had scored. One of Herr Hitler's elite fighter groups needed plenty of replacements of both planes and pilots!

Our skipper's voice came over the intercom, checking his crew and the damage sustained. But it was a short recess. The nose gunner interrupted the skipper to point out a burst of small black puffs dead ahead. We all knew the answer to that one-FLAK!

And how we hated it! A moment before, we'd been looking proudly down at the smoking ruins of the airdrome we had been sent to destroy.

Now, the AA Heinies were showing us there were still a few 88's and 120's which we hadn't knocked out! Their range was pretty accurate and the "sausage factory" guardians were letting us have the works!

It was not pleasant. Flak is nasty stuff! . . . There is just about nothing a fellow can do about it but sweat it out and pray like hell! In a fighter attack, you can hit back; but against ground fire the best gunner in the AAF is just a fuming frustrated kid!

We got through it somehow and out of their patterns. Then the tail gunner buzzed the interphone: "Four of 'em at 10 o'clock-coming in-and fast!"

Good Lord! Jerry fighters again! And we had an enginegone, the prop feathered! Out of one hell-into another-and back to the first again! My pores immediately gave me another sweat bath, but I automatically slid a fresh batch of plates into the old picture box, and glanced over at Tom and Blinky. They had assumed their characteristic firing poses—and Blinky had stopped blinking. He forgot that little nervous habit when he was peering over those pet .50's of his! "Here we go again," I thought. "Maybe 'these negatives will be smashed into a million pieces, but as long as the guns are manned this is what I'm here for!"

Suddenly my earphones almost tore my drums apart! Our navigator, chiseling in on the precious space in the ball turret, had identified the fast-closing single-engine jobs. "P5l's," he screamed into the intercom. "Allah and Hap Arnold be praised! Here come the prettiest pieces of flying junk in the wholeg—d—world. . . . Don't shoot! They've come to tuck Baby safely in bed!"

A few weeks later we were informed that our group had been awarded a Presidential Citation for the work we had done on our target that day. There was no special mention of the work our gunners did but we knew. And I feel safe in saying the Nazi High Command knew, too—and did a heap of griping over the way American gunners can shoot!