A selection of 20th Century U.S. military revolvers includes (counter-clockwise from top l.): a S&W Victory Model, serial No. “V3” that belonged to Maj. Gen. Julian S. Hatcher (V1 was presented to Harry S Truman); U.S.N. Capt. J.H. Wesson’s S&W M1917 engraved with his name and the Naval Academy seal; a Colt M1917 .45 ACP cal.; a Colt Model 1894 U.S. Army .38 DA; and a blued M13 “Aircrewman.” Artifacts and arms are courtesy of the U.S. Marine Corps Air-Ground Museum, Quantico, Virginia, the National Firearms Museum, Rick Nahas, Phil Schreier, Doug Wicklund and Mark Keefe.

This article was first published in American Rifleman, May 1997

Though some fixed- cartridge revolvers were used during the American Civil War, it wasn’t until the U.S. Army officially adopted the now-famous Colt Single Action Army revolver in .45 Colt cal. in 1873 that the cartridge revolver came into its own in U.S. military service. The solid-frame SAA was rugged and reliable, and it provided valuable service to our soldiers. Smaller numbers of break-open S&W .45 revolvers were also acquired, primarily the “Schofield” models that could be loaded and ejected faster than was possible with the Colt.

Colt .38 Double Actions

By the early 1880s, however, another revolver type was under active consideration as a possible replacement for the single-action. Colt had developed a solid-frame revolver with a swing-out cylinder and a double-action trigger mechanism. It had the advantage of a solid frame (thus overcoming one of the primary criticisms of the early S&Ws), but allowed for rapid loading and ejection. It was also felt in some circles that a smaller caliber, higher-velocity cartridge would be better for military use than the heavy .45 round.

After official tests and evaluation, the U.S. Navy ordered 5,000 Colts and they were adopted as the Navy’s “Model of 1889.” In 1892, an improved version was adopted by the U.S. Army as the “Model of 1892.” Between 1892 and 1905, several slightly improved variants were adopted by the U.S. Army, Navy and Marine Corps. During the Spanish-American War in 1898 and the subsequent campaigns in the Philippines, these .38s saw a surprisingly amount of combat use. Although the double-action mechanism was satisfactory, the rather anemic .38 Long Colt round was found to be woefully inadequate.

Some 3,000 obsolescent M1873 Single Action Army revolvers were refurbished and issued for use in the interim until the situation could be addressed and evaluated. The last U.S. Army procurement of the .38 Long Colt cal. revolvers was in 1903 and the last Marine revolvers of this type were purchased in 1907.

The U.S. also adopted variants of S&W’s then-new .38 Hand Ejector (HE) Military & Police swing-out, double-action revolver. In 1900, the Navy had 1,000 revolvers delivered, while the Army’s 1,000 were delivered in 1901. The Navy guns had their own markings on the butt and serial number range (1-1000). The “U.S. Army Model 1899” guns were numbered from 13001-14000 in S&W’s factory range. The Navy subsequently purchased another 1000 of the 2nd Model.

Colt Model of 1909 .45

Extensive testing revealed that a .45 cal. handgun cartridge was optimum for combat use, and the military expressed a desire for a semi-automatic .45 cal. pistol. However, while development of a suitable self-loader was underway, the Ordnance Department considered what type of handguns should be procured to address the immediate problem. Although the .38 Long Colt cartridge was clearly not up to the task, the double-action revolver, while not as desirable as a modern self-loading pistol, was felt to be satisfactory.

From 1907 to 1909, Ordnance tested a Colt large, heavy frame double-action revolver. The gun was designated by Colt as the “New Service,” and in 1909 it was adopted by the U.S. Army, Navy and Marine Corps as the “Model of 1909.” The new revolver was chambered for what was essentially a smokeless version of the tried and proven .45 Colt used since 1873. From February 1909 through April 1911, some 14,000 of the big .45 cal. Colts were procured, and a few of them saw service in the closing stages of the Philippine campaigns.

In 1911, the government adopted the famed Colt “Model of 1911” semi-automatic pistol chambered for .45 ACP. The M1911 was justly praised as the best military handgun of its day (and for a great many years afterward). It was the general consensus of the time that the appearance of an effective, powerful and reliable semi-automatic pistol permanently spelled the end of the revolver’s role as a military handgun. In spite of the M1911’s unquestionable excellence, the revolver’s days as a military arm were far from over.

Model of 1917 Revolvers—Colt and Smith & Wesson .45 ACP

By 1917, the M1911 was well established, and the small pre-war military was fairly well equipped with M1911s before war was declared on Germany in 1917. Armaments of all sorts were in short supply due to our rapidly expanding military. M1911 production at Colt was stepped up, but other sources were definitely needed. Springfield Armory was too burdened with M1903 Rifle production to resume M1911 manufacture so the government looked to civilian arms makers. Several commercial firms began plans to produce M1911s under contract, but the time required to find suitable factory space, set up tooling and train the necessary workmen created an unacceptable time lag. The only viable solution to the troubling shortage of military handguns was to find another way to supplement the M1911. Fortunately a source of such handguns was available.

The Model 1909 had proven to be a reliable and effective arm, and it could be put back into production at Colt with minimum delay since the work force and production tooling were still largely intact. In fact, the British had purchased a number of New Services in .455 cal. between 1915 and 1917. The only substantive change required was to modify it to fire .45 ACP cartridges. This posed a bit of a problem, however, as the .45 ACP was not well suited for use in a revolver as the extractor could not engage the rimless cartridge. An ingenious stamped sheet metal “half-moon” clip solved the problem. Each half-moon held three cartridges and allowed the rimless .45 ACP to be engaged by the revolver’s extractor.

The modified Colt was adopted as the “Model of 1917” and classified as “Substitute Standard.” The first 50,000 Colt M1917s had straight “unstepped” chambers and would not function without the use of the half-moon clips. Later production Colts were made with stepped cylinder chambers and could be fired without the clips, but cases had to be removed by hand.

The government also approached S&W regarding procurement of military revolvers. S&W had introduced its own large-caliber (.44) heavy frame-revolver, the “New Century” or Hand Ejector, in 1906 based on its earlier .38 cal. double-action swing-out cylinder revolvers. The British had purchased a number of S&Ws in 1915 chambered for the .455 cartridge. The first 5,000 supplied to Great Britain were standard commercial production S&W revolvers modified to accept the slightly larger diameter British cartridge. As was the case with Colt, S&W still had the production equipment and trained work force in place and could deliver handguns to the U.S. military with a minimum of delay. The S&W, chambered for .45 ACP, was adopted by the U.S. and given the same “Model of 1917” and “Substitute Standard” designations as the Colt. S&W began M1917 production on October 27, 1917. The S&W M1917 revolvers all had stepped cylinder chambers, allowing use without half-moon clips although the fired cases, too, had to be manually extracted.

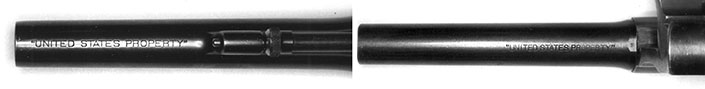

M1917s produced by both firms had blue finishes and had plain, uncheckered walnut stocks with a lanyard ring attached to the butt. The model designation and serial number were stamped on the butt, and “United States Property” was marked on the bottom of the barrel. Leather holsters essentially identical to the M1909 holsters were adopted and given the same “Model of 1917” designation. They were designed to be worn with the butt facing forward in the manner preferred by the cavalry. A canvas pouch holding three pairs of half-moon clips was also issued for use with the M1917 revolvers.

As the U.S. forces rapidly expanded, more and more of the big S&W and Colt revolvers were carried into combat by the American Expeditionary Force. They were well made and the potent .45 ACP cartridge was an effective round whether fired from a pistol or a revolver. Given the opportunity to choose, most doughboys would likely have picked the M1911, but a number selected the M1917 revolver even when the semi-automatics were available. By the time of the Armistice in November 1917, there were a surprising number of M1917 revolvers in the hands of our troops. One government report pointed out that although the M1911 pistol was the standard issue, almost 2/3 as many of the “Substitute Standard” M1917 revolvers were produced and issued during the war.

M1917 production ceased in early 1919, by which time Colt had manufactured approximately 151,700 and S&W 153,300. Most M1917s were retired to the war reserve stockpile and the M1911 remained the standard-issue handgun.

The 1920s and 1930s were a time of almost total stagnation in the design and procurement of military handguns. There was an ample supply of First World War-vintage arms on hand that more than met the needs of the small post-war military.

However, the outbreak of war in Europe in 1939 eventually resulted in an assessment of the adequacy of America’s military readiness. As was the case almost a quarter of a century earlier, our armed forces were unprepared to fight a major war. All types of military armaments were needed and handguns were no exception. Production of the standard M1911A1 .45 pistol was greatly increased but the demand far outstripped production. World War I-vintage M1917 revolvers still in war reserve were called back into service. Ordnance Department records indicate that 188,120 M1917s were in inventory as of November 1, 1940 (96,530 Colt and 91,590 S&W), and many needed refurbishing before issue. During the overhaul process, most of these re-issued M1917s were refinished in parkerizing and the original walnut stocks replaced by plastic ones. The majority of them were issued to Military Police units and security personnel stateside, but 20,993 M1917s were sent overseas and issued to combat troops in both Europe and the Pacific. However, the utilization of M1917s was only a partial solution to the pressing shortages of military handguns.

S&W “Victory Model”

Our British allies were also faced with severe shortages of arms prior to the America’s entry into World War II. A number of American firms were approached with contract proposals to manufacture arms for Great Britain. S&W manufactured large numbers of its Military & Police model (M&P) revolver for the British chambered for .38 S&W, which accepted the British military “.38-200” (.38 cal. 200-gr. bullet) cartridge.

All U.S. service branches were faced with a handgun shortage. However, the Navy was particularly affected since most of the new production M1911A1s were earmarked for the Army. The Navy contracted with S&W for a sizable quantity of revolvers similar to those produced for the British, except chambered for the .38 Spl. cartridge and with the barrel length reduced to 4". The U.S. contract guns were finished in dull, non-reflective parkerizing rather than a commercial blued finish. The revolver was dubbed the “Victory Model” and the serial numbers were preceded by a “V.”

By April 1942, S&W was in full production of Victory Models, and by the time production ceased, some 900,000 were delivered to the U.S. government. Many were carried by Navy and Marine aviators (such as the one reportedly carried by “Pappy” Boyington on this month’s cover) and others were supplied to plant guards and other security personnel. It has been verified that some of the Victory Models were carried into combat by Marine Raiders. In December 1944, a hammer block safety device was added to the Victory Model after an accidental discharge aboard a ship that killed a sailor. The serial number prefix was changed to “VS” on subsequent production guns to indicate that change. A 2"-barrelled version was also produced but in very limited numbers.

Colt “Commando”

In addition to the Victory Model, the government procured more than 45,000 .38 Spl. revolvers from Colt during the Second World War. It was a slightly modified a version of the Official Police with a 4" barrel, parkerized finish and plastic stocks given the somewhat fanciful “Commando” name. The Commando was in production from 1942 through early 1945 and was distributed primarily by the Defense Supplies Corp. to guards and other non-military personnel. Issue of the Commando revolvers to military personnel was limited. A 2"-barrelled version was made in limited numbers and was referred to as the “Junior Commando” in government records.

Along with the Victory Model and Commando, the government acquired a limited quantity of standard commercial production .38 Spl. revolvers including a number of Colt Official Police revolvers with 4" barrels. Some Colt “Detective Special” and S&W “Military and Police” models with 2" barrels were acquired by the government during this period for issue to investigative and security personnel.

Following the conclusion of World War II, the M1911A1 .45 pistol remained firmly entrenched as the U.S.’s standard issue military handgun. Large quantities were left over and, in fact, the supply was sufficient to meet the needs of our armed forces until the late 1980s.

Even though the .45 remained the standard issue combat sidearm, a surprising number of revolvers were issued to the military after 1945. Such personnel as Air Force security personnel, pilots and similar non-infantry types were often issued revolvers. These were generally commercial pattern .38 Spl. revolvers that were either left over from stocks or were procured in relatively small quantities directly from civilian arms makers (typically Colt or S&W) to meet the limited demand. Such guns were often over-stamped with various types of U.S. property markings.

USAF M13 “Aircrewman”

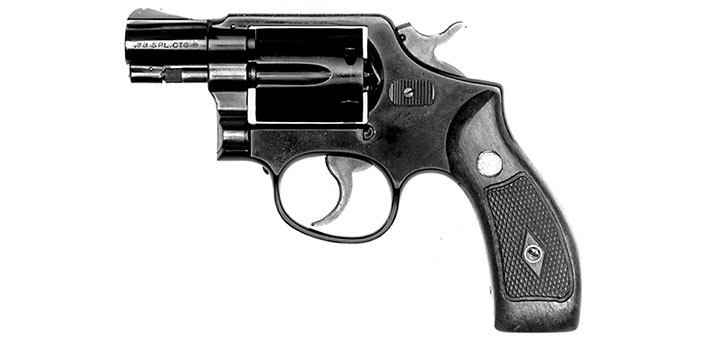

In addition to the commercial pattern revolvers acquired by the government, there was an interesting revolver specifically designed and produced for the U.S. Air Force following World War II. In the early 1950s, the newly-independent Air Force was interested in obtaining a lightweight and compact revolver to arm aircraft crewmen. Colt submitted a .38 Spl. revolver with a cylinder and frame of aluminum alloy and a 2" steel barrel to the Air Force for consideration. The design was acceptable and was designated as “Revolver, Lightweight, Caliber .38 Special, M13.” The new revolver was dubbed the “Aircrewman” and procurement began in mid to late 1951. In 1953, S&W was also given a contract for its version of the same type of arm based on the company’s K-frame Model 12. Both the Colt and S&W were given the same “M13” nomenclature.

The M13 Colts were marked “Aircrewman” on the left side of the barrel and both the Colt and S&W guns had “Property of U.S. Air Force” stamped on the back straps. The Colt M13 revolvers were serially numbered in a special range with an “A.F.” (Air Force) prefix (“A.F. 1” to “A.F. 1189”). S&W M13 revolvers did not all have “A.F” prefixes and were numbered in the normal Smith & Wesson serial number sequence of the period. The M13 revolvers were issued with special leather holsters and cleaning equipment.

Due to their aluminum cylinders, the M13s were designed to be used with a specially developed .38 Spl. cartridge adopted as the M41. This anemic round utilized a 130-gr. FMJ bullet and produced lower pressures than standard .38 Spl. loads. The firing of standard .38 Spl. cartridges in the aluminum cylinders could potentially be quite unsafe. The M13s were issued by the Air Force until the latter part of 1959 when they were withdrawn from service. In October of 1959, M13s were ordered to be turned in and destroyed. The most common method of destruction was to mutilate the aluminum frames and cylinders with cutting torches. The remains were then disposed of as scrap and relatively few M13s survived. Some partially restored M13s are seen from time to time, but original, unaltered specimens are quite scarce today, and M13s are often faked. Despite its limited tenure of duty, the M13 is unique as it was the only revolver specifically designed for use by the U.S. Air Force. The advantages gained in weight reduction were not worth the problems created and the Air Force procured standard .38 Spl. revolvers, mainly S&W M&Ps, to meet its needs after the demise of the Aircrewman revolver.

Ruger “Service Six” Military Revolver

By the late 1970s, the military required new handguns to replace the aging .38 Spl. revolvers in the hands of Air Force and Army military police and Navy shore patrol personnel. In December 1977, the government ordered some 6,500 of the new Ruger Service Six .38 Spl. revolvers with 4" barrels. These were very similar to commercial-production Rugers, but were numbered in the “153” prefix range, marked “US” on the receiver and fitted with lanyard swivels. The guns were among the last revolvers to be ordered by the U.S. government for military use and many still remain in service today.

Although often denigrated as a combat arm during the past 75 or so years, the revolver has proven its worth many times. While the advantages of the self-loading pistol for military use are obvious, revolvers have nevertheless provided valuable service to our armed forces on countless battlefields around the globe.

Despite being in the shadow of the outstanding M1911A1 .45 autoloading pistol, the revolver’s role as an American military arm should not be overlooked. For an arm that has been declared by many as “obsolete” since at least the turn of the century, the revolver has served this nation’s armed forces with distinction for nearly all of the 20th Century.