Originally printed in Arms And The Man, October 6, 1917

Around the time-tried Springfield, Model 1903, has been constructed an excellent twenty-five shot periscope trench rifle. With it, accurately aimed shots can be fired while the soldier is thoroughly protected by an overhanging trench parapet. The sighting equipment is practically telescopic as well as periscopic, permits of micrometer windage and elevation adjustments and is equipped with "intensifying screens" which bring clear definitions to hazy targets.

In brief, these refinements have been accomplished by an auxiliary magazine and a new form of periscope, both of which have been adjusted to the Springfield, as issued, while the rifle itself is mounted upon a framework fitted with an extension trigger and bolt action acting in sympathy with the trigger and bolt action of the rifle. By many who have examined the rifle each of the improvements apparent in the new trench outfit is declared to be a successful attempt to meet shooting conditions as they exist along the Western front.

As the first perfected models stand, the entire outfit adds about 6 pounds to the normal weight of the Springfield. It is, however, easily mobile, and since designed for trench work only, the increase in weight is not regarded as a fatal defect. It is probable that in later models a marked reduction in weight will be apparent.

The outfit has been thoroughly tested, and has now been submitted to the United States Ordnance Department. It has proved practical in previous tests and evidences a high degree of accuracy, with a marked reduction in the usual recoil which follows the heavy service charge. It is also possible, with the outfit to “stay on the target” for long strings without stopping to readjust sights.

Scores of inventors, spurred by the coming of war, have during the past few months been at work upon improvement and refinements for the Springfield. Many of these proposed innovations, which range all the way from new forms of receiver sights, to auxiliary battle sights, will prove utterly impracticable. Others, while practical, will no doubt be disapproved by the War Department, since any change which involves the manufacture of special parts is frowned upon at this time; a fact which most likely explains why the Nash Receiver Sight, operating with perfect success during the Navy tryout, has not been finally passed upon by the army, since to mount this sight requires retooling of the receiver and a remodeling of the stock.

When James L. Cameron and Lawrence E. Yaggi both of Cleveland Ohio, and enthusiastic riflemen—Mr. Yaggi being a member of the N. R. A.—undertook to perfect certain devices for the Springfield, they bore in mind the necessity of adopting their accessories without radically changing the service arm, and accomplished their improvements on this principle.

The Yaggi-Cameron periscope Springfield made its appearance on the Winthrop, Md., rifle range about three months ago. Yaggi was demonstrating its possibilities. Among the interested spectators was Col. C. B. Winder, whose name has long been associated with those of the men who consistently enter long range matches. Colonel Winder incidentally had just installed at Winthrop a new target marker as well as a unique form of range desk.

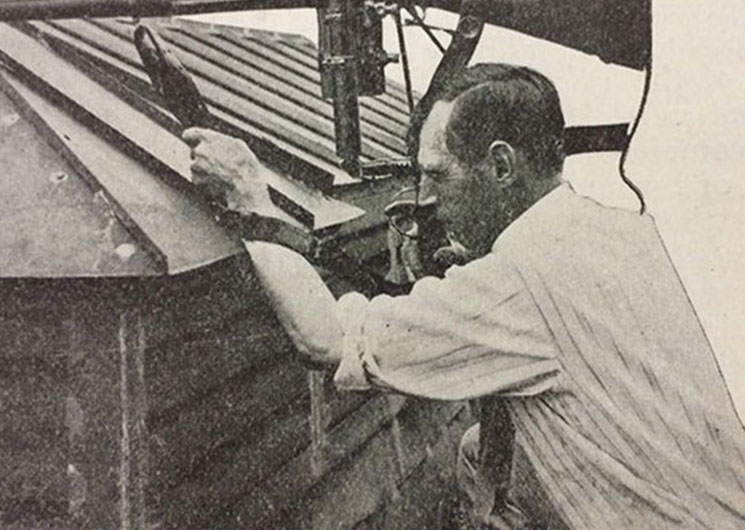

Colonel Winder saw Yaggi slip the heel of the rifle into a boot, which surmounted a light iron framework of peculiar design and then fasten the rifle to another part of the frame by a band which fitted around the small of the stock. He saw Yaggi unsnap the magazine floor-plate, substitute the 25-cartridge magazine, and adjust the extension which “lets off” the rifle trigger. But more than that he had seen a peculiar, goose-necked tube which ran down beside the frame work from beside the rear sight. The goose-necked tube appeared to carry a lens. That in itself was quite enough to win the interest of Colonel Winder who is perhaps the greatest telescopic sight enthusiast extant.

The Colonel well knows the kick of the service rifle. He began resisting the “pound” of a military charge in the days of the Forty-five Seventy. He learned more about it with the Krag and completed his education with a score of Springfields. About the first thing that the peculiar framework suggested to the Colonel was KICK.

But when Yaggi fired the rifle he seemed to experience no inconvenience. Colonel Winder, however, wanted to see for himself. Therefore he obtained permission to try the rifle.

Afterwards, describing the effect of the heavy service charge on the weapon held in the light framework, he said: “There was a lot less kick to it than the rifle ordinarily gives. The whole framework, rifle and all, just seemed to rock back a little.”

Cameron and Yaggi perfected their periscope attachment near Cleveland, after it had been tried out abroad under service conditions, Yaggi having himself taken it to the battlefields of Europe where the Tommies and the Poilus disgusted with the box-periscopes which had been issued to them were throwing away that part of their equipment, since the continental forms of periscope betray the hidden sniper by reflection from the lenses, as well as make it impossible for the riflemen to cuddle under the overhanging parapet of a trench and there be safe from shrapnel fire.

Yaggi's periscope does not reflect light. In addition it gives a “cross hair aim” and the lenses give a magnification of about 4-power. When the rifle “lets off” instead of the eyepiece of the periscope jamming back into the rifleman's eye, as so many of the earlier forms were wont to do, the eye piece, by the rocking motion imparted to the frame is carried away from the eye. The intensifying lens which has been developed for use in connection with the periscope, shades out many of the light rays which tend to make distant targets indistinct, and adds about 100 per cent of visibility to a misty foe.

While the "sightascope" as the periscope is called by Yaggi, and the framework are adaptable to both the Springfield and the Enfield rifle, it can also be successfully attached to the lighter forms of machine guns, such as the Lewis.

As to the accuracy obtainable with this device, with sights set for 200 yards, and using a parapet rest, during one of the tests to which the outfit was subjected, 10 shots were fired. The point of impact of these 10 shots varied only 1.3 inches.

While the United States and almost every other government has for the past decade, been endeavoring to develop a machine rifle, in even a truer sense than is the Lewis gun or the light Vickers-Maxim, Yaggi and Cameron have, in their auxiliary, detachable magazine approximated everything to be desired in such an arm save the automatic principle. And, although it is necessary to pull the trigger for each shot, it is possible to fire 25 aimed shots from the magazine in less than half a minute.

The Yaggi-Cameron magazine, which gives the Springfield an appearance not unlike that of the old 10-shot Short Enfield, with protruding magazine, is extremely simple. It consists of nothing more than a metal casing, open top and bottom. Inside of it is an ordinary Springfield magazine feeder, resting upon two Springfield magazine springs which have been joined. The top of the casing is constructed so that it will snap into the fastenings which ordinarily hold the magazine floor plate. The bottom of the casing is made to receive the rifle magazine floor-plate and spring which have been detached. The double spring and feeder, in the casing, and the original floor-plate, spring, and feeder work in perfect harmony in feeding the 25 cartridges into the receiver.

Yaggi has not entirely confined his efforts to producing the periscope Springfield. He is a great believer in the protective coloration idea in uniforms—also that rifle sights should be constructed to give the greatest visibility possible to misty targets. This latter theory led him to the production of something else absolutely new in sighting equipment. In short, he has devised a front sight of red Bakelite and a rear sight slide of green Bakelite—a substance quite as durable as steel for this particular purpose—which produces a far clearer definition of an obscure target than do the ordinary sights.

While on the battlefields of Europe, Yaggi conceived the idea which has developed into his “colored sights.” As a matter of fact the idea, in practice is not quite so absurd as it may sound. There are very good scientific reasons to be presented for such a course, according to Yaggi and other riflemen who have experienced the eye-strain attendant upon iron sights set far from the eye.

The inventor of the colored sight system points out that to pick up a human target garbed with consideration for protective coloration, is a very different matter from lining up sights on a black bull's-eye against a white background. And it is often an almost impossible task to spot the misty gray uniform of a German sniper through a misty atmosphere, and obtain anything like a clear definition.

Having observed these difficulties encountered by the snipers on the battle fronts of France, Mr. Yaggi set about obtaining some material which could be colored so as to absorb rays rather than reflect them, and which, by contrast would prevent confusion between front and rear sight, as well as diseases or some disturbances of the nerves governing the eyes may render shooting difficult, but the next time you hear a near-sighted or far-sighted man say he cannot shoot because he is that way, rest assured that his bad shooting is not the cause of eye trouble and that he is simply handing out one of the thousand and one excuses which are always on tap when the scorer chalks up a poor total.

It is well for any man who intends to do a lot of rifle shooting to have his eyes examined by a competent oculist, and preferably by one who is a shooter himself. You may have no trouble at all, but it is well to be on the safe side, because shooting—especially in a poor light—calls for considerable exertion on the part of the eyes and if there is trouble of any kind it is sure to aggravate it.