In the gun industry, this is an old and often repeated tale. A company—in this case, Colt—decides to cease production of one of its iconic products, then finds itself scrambling to reintroduce it after another company takes up manufacturing a clone of the original. Historically, most gun companies have sought to provide their products to governments—so-called military contracts—because they are lucrative and guarantee sales for a period of time. During war time most firearm companies retool and set up to provide arms for the war effort.

So it was in 1941 when we entered World War II that Colt ceased producing its flagship gun, the Single Action Army (SAA). When the war ended, Colt said it would no longer produce the SAA, believing that double-action revolvers and semi-automatic pistols were the guns of the future. That may have been true, but the bosses at Colt did not realize the impact the single-action revolver had on Americans. Bill Ruger, a gifted designer and lover of guns, recognized the needs and desires of the shooting public, especially as the 1950s brought television programming to nearly every household in the country and the popularity of westerns in the social fabric of the public. His Blackhawk revolvers were an immediate and lucrative success, thus pretty well spanking the pants off Colt.

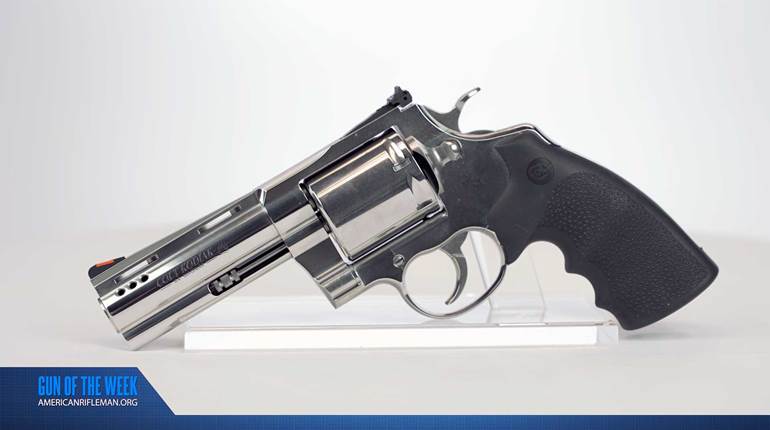

Colt scrambled to reintroduce its archetypal thumb-buster and did so in 1956. There was also clearly a burgeoning market for a rimfire single action, as evidenced by the success of Ruger’s Single Six introduced in 1953. Just as today, the development of a new product pits the bean counters against the designers in a conflict of quality vis-à-vis cost of production and price point. A year after reintroducing the SAA, Colt brought out the Frontier Scout 22 chambered in the Long Rifle cartridge. It had a decent run, ceasing production in 1970. The biggest complaint against the Frontier Scout was the anodized aluminum frame. Colt’s brass listened to its customers and brought out the New Frontier Scout with a companion .22 WMR cylinder in 1970. The frame was steel and featured Colt’s famous color casehardening. Three barrel lengths were offered, 4 3/4-inch (somewhat rare), 6-inch (most prevalent) and a very few Buntlines with a 7 1/2-inch barrel.

Four years later I had barely turned 21 and had a burning desire to learn how to shoot a handgun. My family was not gun or outdoors people. I knew I was ignorant and read every gun magazine and book I could lay my hands upon. Standing at the handgun counter of a Big 5 Sporting Goods store in Torrance, Calif., I gazed upon two nearly identical single-action .22s—a Ruger Single Six and a Colt New Frontier Scout. Both had an extra cylinder in .22 WMR, a real bargain I thought, and I was right. The Ruger had a price tag of $98; the Colt was $10 more. I mulled over everything I could in my scant knowledge of guns. The clerk behind the counter was of no help. I finally settled on the Colt because I thought it was prettier, and it was only a sawbuck more. This was one of the very few times in my life where making a decision based upon beauty didn’t have unexpected and disagreeable consequences.

The little Colt immediately became my constant companion on the desert and mountain backpacking sojourns. I shot the hell out of it and eventually became fairly proficient at busting bunnies, ground squirrels and snakes. Forty years later it remains with me and is often with me on any varmint shoot.

Colt scaled down the entire revolver to make it handle similarly to the SAA with the rimfire rounds. The New Frontier Scout comes in at about 80 percent the size and weight of a SAA, yet the grip size and profile are identical. At .3 ounce less than 2 pounds, the New Frontier Scout is 10 ounces lighter than a center-fire SAA. This allows the rimfire revolver to handle quicker than its pappy, yet retain enough heft to absorb the already mild recoil of the .22 LR, making it a great small-game pistol. With the .22 WMR cylinder there is certainly more recoil, but not enough to be a distraction. However, the .22 WMR’s report is substantial from a short barrel and can be distracting.

The New Frontier Scout had an initial run from 1970 through 1977 with some 100,000 copies made. Though not particularly rare, it seems that those of us who have bought one tend to want to keep it around. Prices for the revolver I bought for $108 in 1974 are from $450 to $700 today, depending upon condition and barrel length. I checked in with Gunbroker.com and saw but four up for sale, and one was a boxed set of a New Frontier Scout with a Frontier Scout (fixed sight version). One of the other three was a post-’82 manufactured New Frontier Scout. From 1982 to 1986 the New Frontier Scout was reintroduced with a cross-bolt safety added to satisfy product-liability attorneys. Its popularity paled compared to the 1970s revolvers with only 19,000 produced.

All of America’s iconic gun manufacturers have had significant challenges impacting their very existence. Each has been forced to reorganize to one extent or another. Colt has had a part in all of this. The business world has several parallels to the natural world, one being if you cannot or will not adapt to changing environment (markets) you are doomed to failure. Ruger recognized the appeal of a single-action rimfire revolver, and the Single Six has been in constant production for 61 years. One can only hope that Colt will take a close and critical look at its past decisions and operations, and make the necessary changes that will allow it to flourish once again. I would hope one of those decisions would be to bring back the New Frontier Scout as it was made in the 1970s. There is a reason so few of them are found for sale in the used gun section.