Take a look at the firing line of any modern revolver match, and you’ll see a preponderance of Smith & Wesson Model 625 revolvers. Many of these were created in the S&W Performance Center and are embellished with the latest innovations to allow a century-old design for faster reloads and more accurate shooting.

To understand the genesis of this superb revolver, one must step back nearly 100 years to the days just prior to World War I. Our hopelessly hoplophobic ally, Britain, found itself on the cusp of war with Germany. It was in the summer of 1914 when Walter Wesson, eldest son of D.B. Wesson and president of Smith & Wesson, received a request from the British government for a revolver chambered in the .455 Mark II cartridge. The factory was already producing the Hand Ejector First Model in .44 S&W Spl.—aka the Triple Lock—so it wasn’t much of a task to screw on a .45-caliber barrel and ream the cylinder to accept the British cartridge.

The Brits responded that the revolver was too heavy, and the lockup and shrouded extractor rod were too closely fitted and prone toward jamming due to dirt encountered in the field. Smith & Wesson set about to address those concerns, but before the redesign was completed the company received an urgent order for more of the prototype revolvers. England entered The Great War on Aug. 4, 1914, and sent a communication to Smith & Wesson that they needed the revolvers immediately. At the end of September 1914 the company shipped 250 Hand Ejector First Model revolvers in .455 Mark II to Britain. These revolvers had 6 1/2-inch barrels.

Production of the Hand Ejector Second Model began in January 1915, and these guns eliminated the third locking lug in the yoke, along with the extractor shroud on the barrel. This production run lasted until Sept. 14, 1916, resulting in a total of 74,755 Hand Ejectors chambered in .455 Mark II. Of that 69,755 were of the Second Model.

At the peak of production for the Brits in 1915, the U.S. seemed to be getting drawn into the fray. Smith & Wesson had been developing a revolver to chamber and fire the then new-fangled .45 ACP cartridge. The problem was in extracting the rimless cartridge cases from the cylinder. Joseph Wesson had assumed the presidency of the company from his brother Walter by this time, and he invented the concept of a stamped-steel half-moon clip that held three cartridges and would engage the extractor star, allowing for extraction and ejection. It was the first speed loader for a revolver.

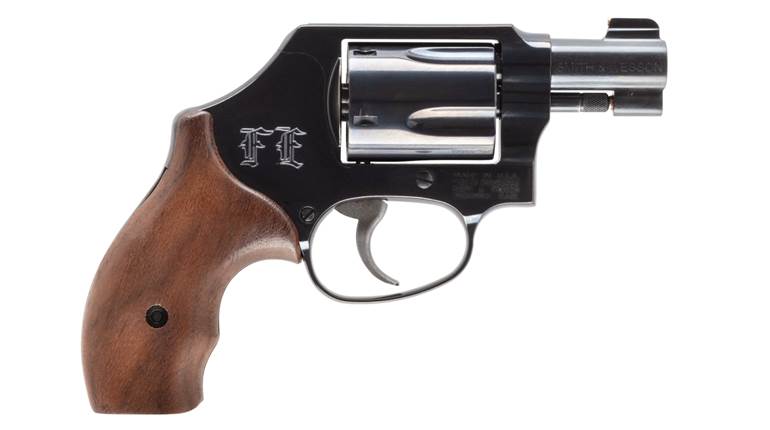

The company was near its limit for production when the U.S. declared war on Germany on April 2, 1917. A new building was being built to expand production capabilities, but Uncle Sam was impatient. The first of the Hand Ejector Second Models made for the U.S. government came off the line on Sept. 6, 1917. These revolvers, dubbed the U.S. Army Model 1917, differed from the British guns in several ways. First, of course, was the chambering—.45 ACP versus .455 Mark II. The U.S. version also sported a lighter 5 1/2-inch barrel. Like the British guns, the stocks were smooth walnut, with a lanyard ring dangling from the butt.

Smith & Wesson did all that it could to satisfy the government’s demand for service revolvers, but it fell short. On Sept. 13, 1918, the government took over the factory, leaving it without Wesson-family control for the first time. At the end of the war the government relinquished its control of the company and returned it to the Wesson family. The company began marketing a commercial version of the popular wartime revolver in 1921, differing from the military model by having checkered walnut grip panels. Versions of this revolver were sold until 1949, though sales were never brisk. In 1937, the company received an order for 25,000 copies of the military-style revolver from the Brazilian government. During its run, some 210,000 Model 1917 revolvers came out of Springfield, Mass.

From these first Hand Ejector models emerged the entire N-frame series of revolvers. Douglass Wesson utilized this frame to introduce the world to magnum handguns—the .357 Mag. specifically—and showed that powerful revolvers were entirely capable of handling big-game hunting. The 1950 and 1955 Target models were the darlings of paper-punching pistoleros for a time, as well as many in law enforcement. Tough, yet elegant, rawboned, yet beautiful, the U.S. Army Model 1917 revolver isn’t some prima donna safe queen. It is a revolver that begs to be shot, and I oblige mine regularly.