"This thing really hammers the ducks,” wrote an NRA member in one of our first “Favorite Firearms” columns about the Browning Auto-5. But the reply from a hunting buddy was, “I’m sure it does, but how do you get them to hold it?” On ducks, and duck hunters, the Auto-5 could pack a wallop. The same cannot be said of the gun reviewed here, the Browning A5 Hunter in 20 gauge. I don’t mean to reduce the original Browning Auto-5 to a mere punchline; it is the product of the genius of John Moses Browning, after all, and was the first semi-automatic shotgun offered for sale, ever. Today, the “aristocrat of shotguns” is still champion when it comes to the longest continuously manufactured scattergun.

Browning filed his patent for a recoil-operated gun in May 1899. Winchester would not give the great man the deal he wanted, and the president of Remington literally expired while Browning waited to show him the gun. So, Browning went to Fabrique Nationale in Herstal, Belgium—FN was already making a handy little pistol of his design. By mid-1902, FN and Browning had a deal—and the first gun was shipped to Utah the following year. Its production ran from 1903 to 1999 across two factories and two continents. Add in Remington and Savage guns made on Browning’s patents (FN only had European rights for a time), and you can up that to four factories and three continents. But it wasn’t until 1958 that the original Auto-5 became available in 20 gauge.

The Auto-5 is often referred to as the “Humpback,” because of the distinctive shape at the upper rear of its receiver, and while the new gun has a similar appearance, it does not share the same method of operation as its namesake. I’m not trying to pick a fight with anyone, but the long-recoil-operated Auto-5 hits pretty hard on both ends—especially if your buffer is cooked or missing. The whole barrel moved rearward, pushing the bolt back the length of a shell, thus it had to have that distinctive shape. There was no recoil mitigation to be had from the hard plastic buttplates of those days, either.

The Auto-5 is often referred to as the “Humpback,” because of the distinctive shape at the upper rear of its receiver, and while the new gun has a similar appearance, it does not share the same method of operation as its namesake. I’m not trying to pick a fight with anyone, but the long-recoil-operated Auto-5 hits pretty hard on both ends—especially if your buffer is cooked or missing. The whole barrel moved rearward, pushing the bolt back the length of a shell, thus it had to have that distinctive shape. There was no recoil mitigation to be had from the hard plastic buttplates of those days, either.

I think the best comparison for the new A5, which we tested more than a decade ago in 12 gauge, as well as the Sweet Sixteen and now the 20-ga. Hunter, is to liken them in concept to the “new” Ford Mustang. These new A5s have the lines, the ethos and some of the soul of the original, but absolutely nothing is the same under the hood. And rightly so, as we have learned a lot about how to make semi-automatic shotguns run well with a wide variety of loads in the past 125 years.

Let’s start with the “hood” itself, and that is the A5 20’s aluminum receiver (original Auto-5 receivers were steel). It is the same size employed on the Sweet Sixteen—9 3/4" long and 2.55" high at the front to 2.75" high at the rear—and has some of the nicest gloss-black anodizing I have seen. Its lines are only spoiled on the left by the two takedown pins for the trigger group and the two screws retaining a steel bar that hold the plunging, spring-loaded ejector in the receiver’s left interior. It plunges due to the different shell lengths the gun can chamber. It also strengthens the receiver for most of the length of the bolt’s travel. There is a bolt release with annular rings on the receiver’s right front under the ejection port. The grooves along the receiver’s top flow into the grooves on the barrel’s vented rib. More on that later.

Unlike the original long-recoil-operated Auto-5, Browning’s new breed of A5s cycle by way of an inertia-actuated Kinematic Drive system featuring a four-lug, rotating bolt head (inset, l.) that locks into the barrel, which allows for a receiver of lightweight aluminum.

A quick note on the trigger assembly pins. The new A5 is very easily disassembled and reassembled. If you read the manual, you should have no issue. I strongly recommend against disassembly of the original Auto-5. If you get it back together without the aid of a gunsmith, there will likely be profanity involved. (Coincidently, the only human I know who enjoys doing this is the senior art director of this magazine.)

Under the hood, it’s obvious that the 1900-1905 patents protecting Swede Carl Sjögren and Benelli’s SL-80 Model 21 are expired. The generic term for such operation is inertia-operated (even though I think it might be classed as a form of hybrid delayed blowback). The brand-specific execution of an inertia gun by Browning is called Kinematic Drive.

Here’s how it works, regardless of what you call it. You start with a two-piece bolt with a heavy body and a rotating head that locks into a barrel extension with a seriously heavy spring between them. When the gun fires, the bolt wants to remain at rest and the moving gun puts the bolt into full lock-up (it usually already is), but as the gun moves farther, once pressures have dropped to a safe level, the spring decompresses, unlocking the head, moving it on its cam pin and driving both parts to the rear. As it moves rearward, it extracts the shell and is returned to battery by a recoil spring in the buttstock worked by a tail at the assembly’s rear. With the Browning, you get four lugs on the polished chrome bolt head instead of two.

Located just forward of the trigger guard, the shotgun’s bolt latch allows the bolt to be locked back on an empty magazine and also releases a shell from the magazine to be loaded into the chamber.

There are some serious benefits to the system: The receiver can be of lightweight aluminum, and, unlike the original Auto-5, regardless of chambering, this gun will handle pretty much everything from all but the lightest target loads all the way to the heaviest of magnums. The original design had two friction rings—one each for heavy or light loads—that you had to decide when to swap. Also, unlike with gas-operated guns, the new design means there is no heat or gas deposited inside the action; it all goes out the muzzle.

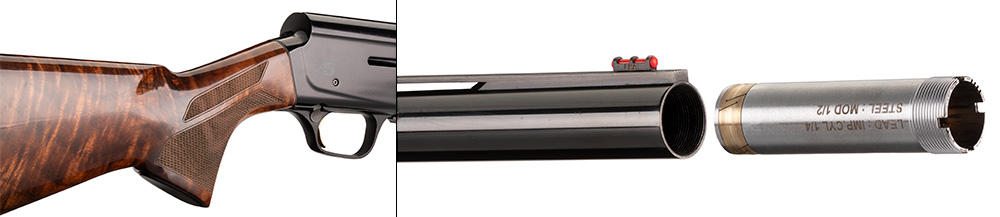

The A5 Hunter 20 Gauge is assembled by Browning Viana in Portugal, but its hammer-forged barrel (with a chrome-lined chamber) is made by FN in Belgium. Like all of today’s Brownings, the 20-ga. A5 Hunter’s barrel is backbored. It measures 0.627" (nominal for 20 gauge is 0.615") and the forcing cone is lengthened out to around 5 1⁄8"; this has been a company hallmark for a very long time. Browning says it delivers better patterns, and many other companies agree and often do the same while calling it something else. The gun comes with three Invector DS (for Double Seal) choke tubes—improved cylinder, modified and full—all of which measured between 0.001" and 0.002" of the constriction recommended for those chokes.

This little gun has Browning’s “Speed Feed” feature. When the bolt is locked back, if you push a round into the magazine tube, the two-piece carrier will grab it, pull the cartridge up into the feedway and then the bolt will go forward. It’s handy. There is a bolt hold-open on the underside of the receiver, with classic Browning lines (a little nostalgia again), and it can be used to lock the bolt back on an empty chamber at any time. Simply press it forward then shuck the bolt handle.

Cut checkering (18 l.p.i.) on the fore-end and the stock’s wrist (l.) both looks good and aids in control of the gun under recoil. The 20-ga. A5 Hunter’s hammer-forged barrel is threaded for use with Invector DS choke (r.) tubes—three of which (improved cylinder, modified and full) come with the shotgun.

Other companies have tried to deal with the lack of recoil reduction in inertia, I mean Kinematic, shotguns. But this one does a very good job due to its Inflex recoil pad—even with the heaviest 20-ga. loads. It’s soft but not sticky, with a wide footprint to spread the energy out, and it is constructed internally to direct recoil back and downward, away from the face. A complaint with my Auto-5 was the stock had too much drop and punched me in the face every time I shot it.

The new gun’s stock aids in not only pointing but also in reducing perceived recoil. It has a fairly straight comb but has a modern pistol grip; the radius of the top is quite thin, but it then expands into a generous palmswell. That is combined with an almost minimalist fore-end. Both are of high-gloss Grade I walnut with panels of 18-l.p.i. cut checkering where the hand interacts with the furniture.

The 20 gauge’s chamber can handle up to 3" shells, and the underbarrel magazine tube can accept three of them with the plug removed; four 2¾" shells will fit the same space.

My test 20-ga. A5 Hunter was patterned with Hevi-Shot Hevi-Hammer Dove loads. The 20-ga., 3", 3/4-oz. load delivers a mixed payload of bismuth and steel No. 7 shot at 1,325 f.p.s., and the results can be found in the accompanying table. Patterns would put the target on top of your bead. When you look at that table, realize we had an improved cylinder choke at 40 yards. I did not have the opportunity to hunt with it before this review, but one of my colleagues was able to get the gun to my favorite dove spot at Quaker Neck in Chestertown, Md., and he said it swung very well. A group then took it to Bull Run Shooting Center in Manassas, Va., for a few rounds of sporting clays. We fired a mix of 3" and 23/4" shells (sometimes loaded into the magazine at the same time) from makers including Federal, Fiocchi, Remington and Winchester. We went the gamut from target to game loads, all in small shot sizes, of course. The Browning didn’t care; no problems or malfunctions occurred throughout our testing.

My test 20-ga. A5 Hunter was patterned with Hevi-Shot Hevi-Hammer Dove loads. The 20-ga., 3", 3/4-oz. load delivers a mixed payload of bismuth and steel No. 7 shot at 1,325 f.p.s., and the results can be found in the accompanying table. Patterns would put the target on top of your bead. When you look at that table, realize we had an improved cylinder choke at 40 yards. I did not have the opportunity to hunt with it before this review, but one of my colleagues was able to get the gun to my favorite dove spot at Quaker Neck in Chestertown, Md., and he said it swung very well. A group then took it to Bull Run Shooting Center in Manassas, Va., for a few rounds of sporting clays. We fired a mix of 3" and 23/4" shells (sometimes loaded into the magazine at the same time) from makers including Federal, Fiocchi, Remington and Winchester. We went the gamut from target to game loads, all in small shot sizes, of course. The Browning didn’t care; no problems or malfunctions occurred throughout our testing.

One of the things that people liked about the original Auto-5 was you got “more sight radius.” I really never thought about that much with my original; I was too busy trying not to have it punch me in the face. When I mount the new gun, though, the spot where my face should be in relation to the back of the receiver is clear: Its grooves lead me to the vented rib, then the mid-rid white bead and then the red LPA fiber-optic front.

I love that this trim, little gun has old-school Browning aesthetics. Everything is shiny. The trigger is gold-plated (my only complaint being that it was a bit squishy, but you’re supposed to slap a shotgun trigger, anyway), and a gold Buckmark tastefully adorns the trigger guard’s aluminum bottom. Best of all, it weighs only 5 lbs., 11 ozs. But it was in the hands that this little gun really comes alive. That slight extra weight of the 16-ga.-size receiver moved the balance point toward the rear and between the hands. It was quick to the target from the shoulder or from a low-gun position. The sample with a 28" barrel made me wonder if I ever need a 26" barrel again.

Interestingly, there may be a role for this 20-ga. A5 fulfilled for years by the Franchi 48 AL, which, to my knowledge, was the last long-recoil-operated shotgun, having a run from 1950 to 2016. In blued steel and walnut, it was the choice for a lot of bobwhite quail hunters throughout the American South—often pulling double-duty on doves. I can see this new A5 slipping very nicely into that arena and expanding into a whole lot more. Lightnings, Micro Medallions, Wicked Wings—a lot of things will be possible for my new best friend.