The .22 Long Rifle cartridge and the guns that chamber it have grown from humble 19th century blackpowder origins into an enormous segment of the firearm industry with sales estimated in the hundreds of thousands of guns and billions of rounds of ammunition per year.

Now, after decades of incremental advances in performance, the perennial favorite “twenty two” has been transformed into a rimfire cartridge fully in step with the technological capabilities of the 21st century. The new cartridge isn’t a .22 at all but rather another .17-cal. rimfire from Hornady called the .17 Hornady Mach 2, or .17 HM2. It is based on the .22 LR hypervelocity case necked down to accept the same .17-cal., 17-gr. Hornady V-Max bullet made famous by its first cousin—the previously released .17 Hornady Magnum Rimfire.

The market for the .17 is, however, arguably very different from that of its magnum predecessor. Many .17 HMR customers are knowledgeable, experienced center-fire shooters and varmint/small game hunters seeking improved rimfire performance to 200 yds. and willing to pay up to twice the price of some .22 Magnum loads to get it.

The .17 HM2 customer, on the other hand, is likely to be a plinker/small game hunter who also wants a cartridge economical enough for pest control as well as for informal target shooting. He needs and wants improved rimfire performance, but only out to 100 yds. or so. He may be less willing to pay substantially higher prices to gain such improved ballistic performance as his ammunition consumption is much greater and his expectation for the new cartridge’s technical attributes is lower.

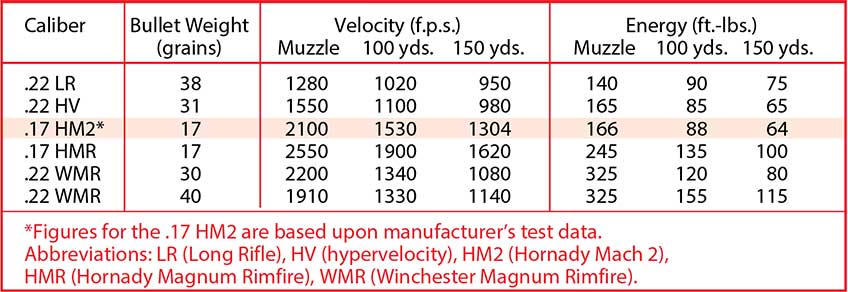

So, what does the .17 HM2 offer compared to the .22 LR hypervelocity rounds? Despite the .17 HM2’s “cute” appearance, the diminutive, bottle-necked red head boasts 82 percent of the muzzle velocity of the .17 HMR and 64 percent greater muzzle velocity than a typical .22 Long Rifle high-velocity load along with substantially flatter trajectory and substantially less wind drift than other rimfires—excepting, of course the .17 HMR.

In short, the .17 HM2 offers an order of magnitude improvement in ballistic performance through greater muzzle velocity, flatter trajectory, a ballistically more efficient bullet, high striking energy, excellent accuracy, elimination of bore leading, reduced ricochet potential, reduced noise levels and significantly reduced lead in the environment. It may, in fact, be the first significant improvement in a widely popular rimfire cartridge in almost 150 years.

Hornady elected to make a “soft” announcement of the cartridge at the 2004 SHOT Show in Las Vegas, consisting only of a flier outlining the cartridge’s performance figures and bearing the image of a prairie dog, paws clasped, under the headline, “Now, varmints really don’t have a prayer.” The company set the .17 HM2’s official launch for the April 2004 NRA Annual Meetings & Exhibits in Pittsburgh. Judging from the reaction of firearm industry members who took notice of the new cartridge at the SHOT Show, the .17 HM2 was likely to create quite a stir among the legions of serious and recreational rimfire shooters after its official rollout.

“It’s a roll of the dice, but I think people will like it,” said Hornady Director of Sales and Marketing Wayne Holt at the time. “[The .17 HM2] lends itself to a lot of shooting with performance added. In the first year we anticipate to produce what demand dictates … if the sales are there, the machines are capable of loading billions of cartridges per year.”

Holt said Hornady’s best-case scenario for the .17 HM2 is that its sales could dwarf those of the .17 HMR, accounting for as much as four times the volume. Considering that Hornady sold 146 million rounds of .17 HMR in 2003, Holt’s guess would mean that more than half a billion .17 HM2 rounds could be consumed within its first year on the market.

Further, Holt added, “You are going to see guns from Ruger, Marlin, Taurus, T/C, Anschutz, NAA, Browning, CZ and Savage.” Such widespread backing is virtually unprecedented in the history of new cartridge development, but is understandable in light of the .17 HM2’s design basis in the .22 LR and its expected price point. When asked about that, Holt estima-ted pricing for a 50-count box of .17 HM2 cartridges, saying, “I would anticipate it would be $6 a box plus or minus.” If that guess proves accurate, the .17 HM2, at 12 cents a round, would fall squarely between the cost of .17 HMR (16 cents a round) and CCI Stinger (8 cents a round).

Even the remote possibility that the .17 HM2 could be the most legitimate heir apparent to date to the vast .22 LR kingdom is enough to make gun manufacturers and other ammunition companies stand up and take notice owing to the enormous volume of yearly gun and ammunition sales.

At last count, more than a dozen firearm manufacturers were actively preparing to support the new cartridge with familiar .22 LR platforms. And recently, industry giant Remington confirmed that it, too, will produce .17 HM2 ammunition.

Hornady’s name for the .17 Mach 2 refers to the combined achievement of its “brains” and its “brawn.” The former is the same red-polymer-tipped 17-gr., Hornady V-Max bullet developed through the company’s bullet-making expertise for its now successful .17 HMR. The tiny jacketed projectile enables higher velocities without leading the bore; its spitzer, boat-tail shape provides a better ballistic coefficient than the round-nose, cup-base bullets used in .22 LR ammunition; and, finally, its precision-drawn jacket improves accuracy.

The latter is a combination of its Stinger hypervelocity .22 LR case, from loading partner CCI of Lewiston, Idaho—which actually produces the cases and loads the ammunition—and a special blend of highly progressive propellant from St. Marks Powders in St. Marks, Fla. Both companies are anything but lightweights, drawing on their corporate parents’ experience as suppliers to U.S. government space and military programs, respectively.

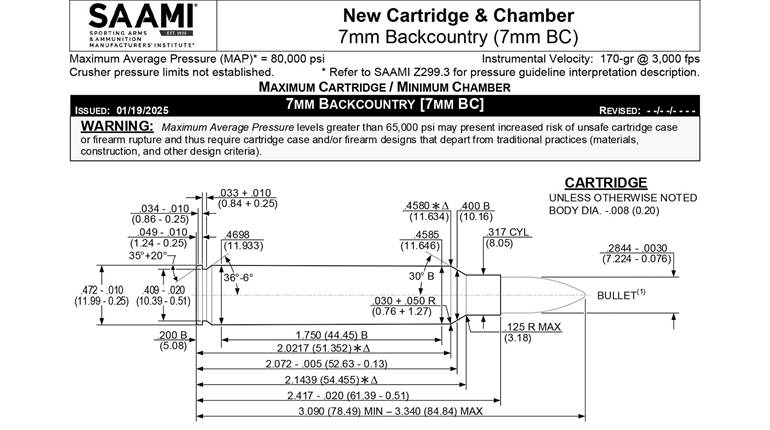

All that technology allows the .17 HM2 to exit the muzzle of a SAAMI rimfire standard 24” pressure and velocity barrel at a stated 2100 f.p.s. While not quite twice the speed of sound, it’s actually Mach 1.875, it is close enough for marketing purposes and gives the .17 HM2 more remaining velocity at 50 yds. than the fastest hyper-velocity .22 LR cartridge has at the muzzle with enough remaining velocity at 150 yds. to keep pace with a standard high-velocity .22 LR bullet at the muzzle. The .17 HM2s real hat trick, though, is that its performance is stuffed into a cartridge overall length of 0.975”—the same as that of the .22 Long Rifle. That means any rimfire platform originally designed for .22 LR should be adaptable to the .17 HM2.

In addition, the cartridge is proving in testing to be, like its more powerful predecessor, highly accurate. But more about that later.

Over the years, various .22 LR-based, small-caliber experiments by both factories and wildcatters attempted to improve rimfire performance, but none found widespread commercial approval. One was the 5 mm Remington Rimfire Magnum, with a muzzle velocity of 2100 f.p.s. More recently, Mexican manufacturer Aguila Ammunition developed its .22 LR-based .17 Aguila, which carried a pointed, jacketed bullet, but achieved only a stated 1850 f.p.s. muzzle velocity and was not backed by major gunmakers.

A brief history of the rimfire family illustrates the .17 HM2’s potential for greatness. In 1831, a French patent for rimfire ignition paved the way for the .17 HM2’s “great-great grandfather” the Flobert BB Cap of 1845. The year 1857 saw the arrival of the Flobert BB’s “son,” the still-surviving and world-standard .22 Short. The .17 HM2’s “great-grandfather,” which came to America with its inventors, gunmakers Horace Smith and Daniel Wesson, became an instant success and remains the oldest American self-contained cartridge still in production. One of its “sons” and the .17 HM2’s “grandfather,” the .22 Long, came along around 1871 and was first to make the transition from black to smokeless powders, which led to the .17 HM2’s “father,” the .22 Long Rifle, in 1887. Its reign would establish it as the all-time king of rimfires in terms of popularity, performance and cost.

The .22 LR or, simply, the “twenty two,” was somewhat old-school with a relatively heavy, 40-gr., bullet as opposed to the .22 Long’s 29-gr. bullet. But the .22 LR was improved over the years in regard to its velocity. Remington did it with modern, progressive propellants around 1930 and, nearly 50 years later, the cartridge was given another boost to the new “hypervelocity” category with brands such as CCI’s Stinger, Winchester’s Xpediter and Federal’s Spitfire.

While the relatively expensive hypervelocity cartridges may have stolen the limelight from the regular Long Rifle and high-velocity .22s, the latter remained the leader in accuracy and economy despite its many inherent design weaknesses. After all, the .22 rimfires’ case-diameter bullets are swaged of lead alloys with cupped bases that must expand under pressure from the propellant gasses to grip rifling. The bullet also must be heavily coated with a wax-based lubricant to prevent leading of the bore. And rimfire priming is notoriously weak, so the bullet must be heavily crimped into the case mouth for proper ignition.

Some of those shortcomings began to be addressed with the circa-1959 .22 Winchester Magnum Rimfire when it began to employ cup-and-draw jacketed bullets in the late 1990s. But it wasn’t until the .22 WMR’s offspring and the .17 HM2’s “first cousin,” the .17 HMR of 2001, came along that high-performance rimfires truly came of age. When the .17 HMR’s advantages over the .22 WMR—flatter trajectory, less wind drift, greater inherent accuracy and reduced ricochet potential—were reported on in American Rifleman, no one knew that only six months later, a similar project involving the necking-down of the .22 LR—what would become the .17 HM2—was already a glimmer in the eye of Hornady Manufacturing Co. Chief Ballistic Scientist Dave Emary.

A conservative, unexcitable type who likes to shoot varmints on the prairie lands outside the company’s Grand Island, Neb., headquarters, Emary is one of a crew of technicians that works to prove and refine the quality and consistency of Hornady’s center-fire rifle and pistol bullets and ammunition. His bosses allowed American Rifleman an exclusive look at the ongoing development of the project at their ballistics lab in January only weeks before Emary expected it to be completed.

At that time, he was spending a lot of time at the loading bench singly dropping miniscule powder charges into pre-primed, necked cases before seating tiny V-Max bullets and placing completed rounds into a loading block. Aside from handloading the world’s rarest rimfire, Emary said he was primarily pre-occupied with “tweaking propellant speeds and tweaking the specs with gun manufacturers to make sure everybody’s on the same page and that this is going to work for everybody.”

That concern about the cartridge’s compatibility with existing .22 LR rifle and pistol designs—especially semi-automatic types—has been at the front of Emary’s mind since the project’s inception. Of those manufacturers that have already committed to produce rifles and handguns for the new cartridge, several were in evidence at Hornady in January, including Ruger’s Standard Model and Browning’s Buck Mark pistols and both Marlin Model 60 and Thompson/Center Classic rifles. Emary described the ejection and bolt operation of the guns tested as “brisk.”

“The .17 HMR came about because the glaring shortfall of rimfires was lack of performance and lack of accuracy,” said Emary. “We got vastly superior ballistics and dramatically better accuracy and made a useful cartridge. As a result of the work we did there, it naturally progressed into, ‘Well, what can we do with a Long Rifle?’

“The thing that you have with a .17-cal. is a bullet with a reasonably good ballistic coefficient. Not only do we have better velocity, you have got substantially better ballistic coefficient, and you are going to have more retained velocity, flatter trajectory and more effectiveness when it gets there. And, yes, it’s going to have a lot less wind drift than a twenty-two.

“This round realistically will have some applications for those who want to do rimfire silhouette and target shooting, too,” said Emary.

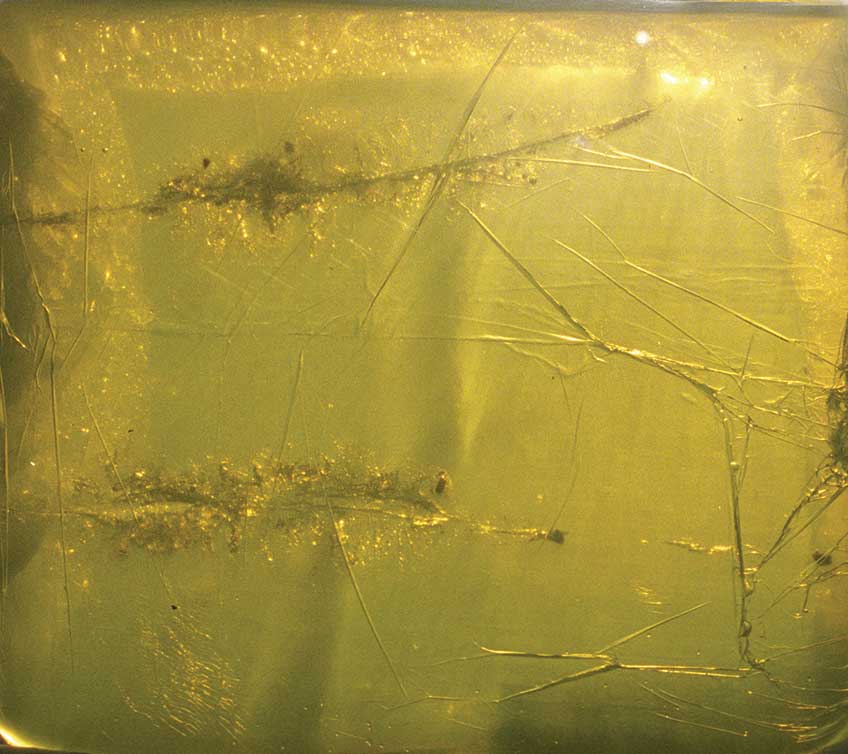

In some ways, Emary’s task was easier than it had been with the .17 HMR. Foremost, the 0.172”-diameter V-Max bullet, with its cup-and-draw jacket, boat-tail and pointed polymer tip, was already being manufactured. The other leg up on the project came from loading partner CCI’s Stinger hyper-velocity .22 LR cases. Only 0.100” longer than a standard Long Rifle case, they nonetheless allowed Emary to pour in enough additional powder before seating the miniature V-Max bullet to make the critical difference. In fact, the .17 HM2’s powder charge is significantly heavier than that of a 22 LR. “Because you don’t have a long 40-gr. .22 bullet sticking into the case … we are up [to] 3 grains plus or minus,” said Emary, which compares with 1.5 grs. for the .22 LR.

Emary categorized the propellant he was then testing in the HM2 as, “highly progressive and in the same category, with a similar composition and chemistry” as the Hodgdon Lil’ Gun canister-grade powder used during development of the .17 HMR. He added, though, that it would “most likely [be] significantly faster.” Development of the new propellant is mostly trial-and-error with regard to how loaded cartridges function in various actions—especially semi-automatics. Emary knew when he began the project that was a key aspect of its development. While the .17 HMR is shot mostly in bolt-actions, the new cartridge—in order to be a commercial success—would have to function well in semi-automatic platforms, which account for much of the mass consumption of inexpensive .22 LR ammunition.

He called it “the key long pole in the tent of the technical aspect of this thing from day one,” and added, “That is where the .17 HM2’s real utility and market penetration is going to be.”

In the final analysis, Emary, while modestly pleased with the shape his creation was taking, remained uncertain whether the shooting public would embrace the new .17 HM2.

“From a performance standpoint it’s an effective 125-yd. cartridge, which you can’t even approach with the .22 LR—and [the .17 HM2] is accuracy-effective for that far, too,” said Emary, citing 11⁄2”, 100-yd. groups he had fired from semi-automatic rifle actions.

That first impression of Emary individually loading the tiny cartridges on a single-station press—a Hornady, of course—remains a lasting one of the man and his paternal nurturing of a newborn rimfire cartridge. The likely reality, though, is that high-speed presses have since been readied to work around the clock in an effort to supply a limitless stream of .17 Hornady Mach 2 clones to the eager masses of rimfire shooters.