The Japanese Type 4 semi-automatic is one of the most sought-after rifles by military collectors. Interest in it spans the spectrum from those who specialize in Japanese military arms to collectors of U.S. M1 Garand rifles to collectors of military rifles in general.

The Type 4 has been erroneously identified as the Type 5 in recent years. In the past, very little was known about development of the rifle. Model identification was established originally through information in a World War II U.S. Army Ordnance report where basic description, history and designation of the rifle as a Type 5 were presented.

In the same report, however, references were made to recovery of Type 4 semi-automatic rifle drawings at Yokosuka Naval Arsenal, which somewhat muddied the water. The Type 5/Type 4 argument has continued among collectors for some time. Examples marked Type 4 have shown up in recent years, and more information has become available that points to the proper nomenclature being Type 4. That said, the Type 4 is still recognized by collectors as a single variation when, in actuality, five variants of this very rare rifle have been identified.

Development of the Type 4 semi-automatic has its roots in an Imperial Japanese Army (IJA) semi-automatic development program initiated in mid-1931. The Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) relied on army arsenals as a source of small arms for land-based personnel, so it sat on the sidelines and watched the IJA semi-automatic development program with special interest.

Initially, in the 1931 timeframe, Nambu Rifle Mfg. Co. was issued a development contract for a semi-automatic rifle intended for army use. Later, the program was expanded to include Tokyo Gas & Electric, Nippon Special Steel (NSS) and Tokyo Army Arsenal (Koishikawa). Nambu initiated development work with a gas-operated design featuring the army-specified five-round magazine. Tokyo Gas & Electric reverse engineered the Czech ZH-29 rifle, examples of which had been captured in Manchuria in 1931.

Nippon Special Steel presented a novel gas-operated toggle configuration, and Koishikawa provided a copy of the American-designed Pedersen rifle. In the case of the Pedersen design, J.D. Pedersen had taken his U.S. Ordnance Dept. trials rifle to Japan in the 1935 period seeking additional interest in the rifle. At the time Pedersen presented his rifle to Japanese army ordnance officers, they were not satisfied with progress on rifle development by private companies, and decided the army should develop a competitive rifle based on the Pedersen design. After all, they were being assured that the U.S. and Great Britain were in the process of adopting the configuration for the using services, so the design must be a winner.

The program, which now included the IJA itself as a contender in development of a satisfactory design, continued until 1937, at which time the program was curtailed. Politics were involved in the decision to stop the program, but of primary importance were the facts that military production was stretched to the limit with the expanding war in China, and it was readily apparent that Japan just did not have the production capacity to build the number of rifles required.

The semi-automatic program was reinstated in 1941. The using services were demanding more firepower, plus military use of semi-automatic rifles was becoming more and more common throughout the world. Since private industry in Japan was so focused on production for the war effort, the IJA set up a competition between two design groups within the army arsenal system, a unit at Kokura Arsenal and the small arms staff at the research center in Tokyo. The program continued until mid-1943 when it was halted because of similar issues faced previously, plus, very importantly, the failure to develop a satisfactory configuration for production.

The IJN was very disappointed in the IJA’s actions. The IJN needed more firepower for its land-based units, and the naval paratroop command desperately wanted a version of the semi-automatic rifle for its units. Japanese navy development of a semi-automatic rifle probably began in some form or other immediately after the army program ceased in mid-1943. Regardless, the program was included in a list of IJN ordnance action items for Fiscal Year 1944 (April 1943–March 1944) with three naval arsenals scheduled to participate—Yokosuka, Kure and Mazrui.

All three, however, were already working at full capacity, so arrangements were made for rifle development to be done on a spare-time basis at Yokosuka Naval Arsenal only. Development of the new rifle was carried out in the machine gun plant of Yokosuka Arsenal, specifically the third floor of the plant, as a spare-time activity in conjunction with production of 25 mm anti-aircraft cannons, Lewis machine guns and Vickers machine guns. With demand for machine gun production so high, priority could not under those circumstances be given to the semi-automatic-rifle program.

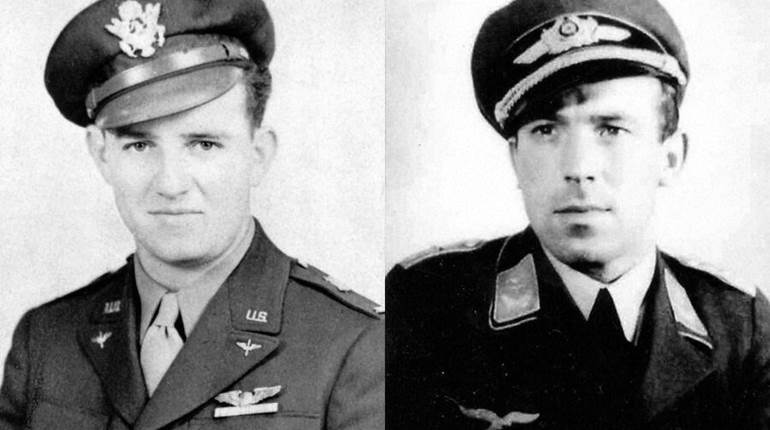

Even though a spare-time activity, the timeline for development of the new rifle remained very short. It has to be assumed that only one rifle was under consideration—the U.S. M1 Garand—because of the short timeline and no evidence of another design being evaluated. Captured samples of the M1 were warehoused at Yokosuka.

Stores of M1s had been found warehoused in Manila after occupation by the Japanese in 1942. Some were transported by the IJN back to Japan. The U.S. M1 represented a successful design in wide use, so IJN engineers decided to modify some of the captured rifles to 7.7x58 mm Japanese, the rimless cartridge standardized for use in the Type 99 bolt-action infantry rifle. In early 1944, 10 rifles were modified to 7.7x58 mm for testing. Functional testing and evaluation proved to be highly satisfactory. This success led to full development of the Garand copy.

First Variation Experimental Type 4 Rifle (Tool Room Example)

The overall brief development period leaves the impression that design and fabrication of the experimental Garand must have proceeded concurrently with modification of the 10 M1s in the early part of 1944. This was a success-oriented program with a lot of objectives to be met in a very short period of time.

Development from the toolroom example to the initiation of production took place during the first 10 months of 1944. Keep in mind that time must have been allowed during that period for tooling design and development, in addition to locating dedicated machinery. Very importantly, an initial effort had to be made to verify that Japanese ordnance had the capability of manufacturing all components of the rifle, some of which are very complex.

What I believe to be the toolroom rifle, or first experimental M1 copy, is functionally very similar to the M1 Garand; however, there are a few key differences. Attempts at simplification and improvement, those changes to the Garand include:

a.) 10-round integral magazine fed by standard five-round stripper clips instead of the M1’s eight-round en bloc clip.

b.) Ramp-type rear sight.

c.) Recoil lug integral with upper buttstock wrist tang instead of recoil absorption through upper stock ferrule.

d.) Lockup of the rifle through hooks attached to the trigger guard, which engage receiver lugs on back of magazine box instead of entering recesses in the receiver.

e.) Trigger housing retained to buttstock with screws instead of falling free during disassembly of the rifle.

f.) Simplified machining of receiver.

The specimen described has no serial number or markings, so it is thought to be the first and only example of its type that was fabricated. If more than one specimen were fabricated, typically, the rifles would be serialized, if only to prevent the mixing of hand-fitted parts.

Machining of the components of the single specimen known is crude where finish is not important to form, fit or function, and the rifle shows haste in fabrication. For example, the barrel, normally a long-lead item, is from a Type 99 rifle and has been modified to fit the new receiver. The Type 99 rear sight was obviously knocked off the barrel with a hammer during rebuild, leaving screw shanks still embedded in the barrel.

The rifle was originally obtained in an incomplete state. Only the barrel and receiver group was available. To complete the rifle to its original configuration, the buttstock and trigger housing group had to be configured and machined. This wasn’t very hard because features on the barrel and receiver group dictated the design of replacement components.

The original rifle probably failed at some point during testing, and the remaining parts were acquired by a veteran as a souvenir. The magazine well has significant powder residue and shows evidence of extensive firing. Most likely, this is the rifle described in U.S. Army Ordnance reports as being introduced to the paratroop command in March 1944.

Features on the toolroom example, plus subsequent test and production models, were required to meet paratroop requirements by configuration. The paratroop command desired a folding or break-down design, shortened in the stored state for transport in a soldier’s pack or leg bag. The U.S. M1 rifle breaks down into multiple segments, one of which is the trigger housing assembly.

The Japanese version, as designed, breaks down into two segments, the difference being the trigger housing assembly is retained to the buttstock group through the use of screws, plus the upper stock ferrule is retained in place via three small nails. The Japanese Type 2 paratrooper rifle, the mainline paratrooper arm at the time, breaks down into two segments; thus, the Japanese M1 copy meets existing IJN paratrooper command requirements. Very importantly, as development of the rifle progressed to the production design, features “c” and “d” were replaced by the tried-and-true equivalent features on the U.S. M1 rifle. Only the novel features “a,” “b” and “e” remained.

A U.S. Army Ordnance bulletin put together in late 1945 presents perhaps the most accurate assessment of Washino’s production effort. The report states that the factory had no production machinery, so it was assembling rifles from parts that were most likely furnished by Yokosuka Arsenal.

Second Variation Experimental Type 4 Rifle

As far as we know, the second variation of the experimental Type 4 rifle exists only in drawing form today. High-quality assembly drawings of the rifle have been recovered from the archives of the Japan Self Defense Force (JSDF) in Tokyo. The drawings show most all of the features of the final configuration of the Type 4, including the revised magazine box with external cap integral with the magazine floorplate. The action-locking features of the first variation are retained, which are locking hooks integral with the trigger guard that engage similar lugs on the backside of the receiver magazine box as the trigger guard is rotated to the closed position, thus locking the rifle components together. The drawing is very detailed and appears to be a production-level drawing, not one of an experimental rifle. It is complete to the point of including accessories, such as a cleaning apparatus and paratrooper accessories such as a waist ammunition belt. So, either the design group was jumping ahead without proof of successful testing, or initial testing with the first prototype had exceeded expectations. No examples of the second variation have been reported, so whether this specimen was actually built is unknown.

Third Variation Experimental Type 4 Rifle

It is only a small step to reach the final Type 4 configuration. The drawings for the second variation incorporate most of the changes to reach the final stage except for the locking mechanism. The third variation substitutes the locking features of the U.S. M1 rifle. Locking lugs on the M1 are configured differently, and enter recesses in the receiver. Rotating and latching the trigger guard locks the assembly together. Keep in mind that the Japanese version had heretofore featured locking lugs external to the magazine box. The IJN may have switched to the M1 design simply to guarantee success in a timely fashion by minimizing any unforeseen development problems.

One example of the experimental third variation has been examined. Typical of the Japanese procedure in serializing experimental production, the rifle exhibits only a small numeral “4” on the front top of the receiver. No other components are marked. Only one specimen so marked has been reported. The rifle shows results of extensive testing with serious bore wear.

Type 4 Pre-Production Rifle For Field Test

With the final configuration set for production, the rifle was adopted by the IJN as the Type 4 rifle. Examples were hurriedly fabricated at Yokosuka Naval Arsenal for field testing prior to mass production. They were reportedly shipped to ground units in China, the islands and to the IJN paratroop command within Japan for extended field tests. That plan could involve a sizable number of rifles, but, most likely, only a handful were distributed.

These rifles exhibited model, arsenal of production and serial numbers on the receiver, along with the month and year of production. The receiver markings on the two examined are inconsistent and hand-engraved, showing a lack of overall process control and also illustrating how fast the program was moving. The rifle with Serial No. 6 has the Yokosuka identification on the line with date of manufacture, while Serial No. 5 has the Yokosuka identification on the line with the serial number. Specimen Serial No. 6 had been examined and found to have all parts matched to the serial number. Only two specimens of this type have been reported.

Type 4 Production (Washino Factory)

Testing of the prototype rifles revealed problems with parts breakage, insufficient recoil and associated feeding difficulties. Even with these problems, testing was considered successful enough to initiate production. Yokosuka Naval Arsenal was not able to support production, so plans were made to shift the work to a private company: Washino Kikai Co., in Aichi-ken.

A U.S. Army Ordnance bulletin put together in late 1945 presents perhaps the most accurate assessment of Washino’s production effort. The report states that the factory had no production machinery, so it was assembling rifles from parts which were most likely furnished by Yokosuka Arsenal. Furthermore, only 50 rifles had been assembled at the war’s end, even though parts for 150 rifles were on hand. None of the rifles had passed final inspection, and the rifles were found in various stages of completion at the factory.

Production of the rifle had stopped prior to war’s end because of functioning problems identified as insufficient recoil from the less powerful 7.7 mm cartridge to eject and chamber another round from the magazine of tested rifles. At Washino Kikai Co., personnel were production-oriented, and no engineer was on staff to solve test problems that may have been encountered, so the company was awaiting instructions from Yokosuka on how to correct the problem and proceed.

While Type 4 production was at a standstill, new orders were received from the IJN to cease production of the rifle in favor of a new aircraft engine contract. When U.S. Ordnance personnel visited the Washino factory in late 1945 after the cessation of hostilities, they found production in the process of switching to an aircraft engine. Even though the production line was being changed, special machinery was at the same time arriving at the factory for rifle parts production. All this illustrates late-war confusion in Japanese production.

I have catalogued 33 Washino-assembled rifles. None are marked externally, indicating no final inspection, but each has an assembly number on the underside of the receiver to match up parts at the assembly stage. The addition of serial number and final inspection symbols were to be added only after successful testing of each rifle. The highest assembly number recorded is No. 58, and that corresponds nicely with U.S. Army Ordnance reported data showing 50 assembled rifles found at the factory at war’s end.