American troops went to war in Korea carrying many of the same weapons that served the U.S. military during World War II. They soon found themselves in combat against North Korean troops carrying their own World War II-vintage small arms. The North Koreans used Soviet-made small arms, the same types used on the Eastern Front.

When the Chinese joined the fight, American troops would be surprised to find their opponents armed with a strange variety of small arms. Some of them were from the Eastern Bloc, others were recycled Japanese arms captured in China during World War II. There were even American-made rifles, submachine and machine guns provided to China via the Lend-Lease Act.

At the beginning of the Korean conflict, the American military was well-equipped for a modern war but rather unprepared for the nature of battle which would take place; an old-fashioned, gut-level infantry struggle across some of the harshest terrain ever fought over.

Eyes on the Sky

On Aug. 29, 1949, the Soviets shocked the world when they detonated their first atomic bomb, the RDS-1. The nuclear “balance of terror” that would define the Cold War had begun. Less than a year later, the Soviets debuted their world-leading MiG-15 jet fighter, and on Nov. 1, 1950, the first jet-versus-jet combat took place when a Soviet pilot named Khominich downed a U.S. Air Force F-80C.

Soviet pilots (called “Honchos” by the U.S.A.F.) covertly flew MiG-15s in North Korean or Communist Chinese air force colors throughout the Korean War. Consequently, America’s military attention was focused on advanced Soviet weapons technology. Soviet-made small arms were otherwise generally overlooked.

Eastern and Western Philosophies in Conflict

As I began to research this article, I sought to gather resources that provided details on Communist small arms from the beginning of the Korean War. I quickly learned such information is nearly non-existent.

U.S. Ordnance was very proud, and rightfully so, of the American arms that proved so crucial to Allied victory in World War II. Axis infantry weapons, particularly the later German designs, were carefully examined and assessed by American weapons experts. Across the board, German designs were judged to be inferior to U.S. weapons.

Certain German concepts, like the “General Purpose Machine Gun” that were the basis of the MG34 and MG42, were explored for later U.S. designs. Other concepts, particularly the MP44 Sturmgewehr “assault rifle” and its intermediate cartridge were not embraced by U.S. Ordnance initially. Work began on improving the M1 Garand, but the M14 rifle that would come to replace it did not enter service until 1958.

After World War II, the Soviets were busily working on small arms to leverage their M43 7.62x39 mm cartridge, which was developed from the German 7.92 mm “Kurz” round. Even so, the now-famous SKS-45 rifle and the AK-47 would not reach standard-issue status until well into the 1950s, and neither one would see service in the Korean War.

The Soviets would supply their Communist allies with the same weapons the Red Army had used so well during World War II. American military leaders overlooked the fact that 80 percent of all German combat casualties in World War II came on the Eastern Front. Those same weapons, considered crude by American standards, coupled with the basic infantry tactics of the Red Army were waiting for U.S. troops in Korea.

In the March 1951 issue of “Popular Science”, editor Perry Githens wrote a review of Communist small arms captured in Korea titled “How Good Are Russian Guns?” Githens writes:

“It is true that many of the Russian-made weapons I saw and handled at Aberdeen Proving Ground look, at first glance, like practice work in a school for lady welders. It is also true that they can kill you very dead at the effective ranges for weapons of their type.

How good are Russian guns? Just exactly good enough and no more. …For Russian weapons are a literal reflection of the harsh Asiatic philosophy that life is cheap. Where men are expendable, so are guns. And if guns are to be lost in the grinding of war we politely call “attrition,” it is better to lose cheap guns.”

I mentioned that pre-Korean War references on Soviet small arms were hard to find. To my knowledge, there was one American arms expert actively writing about Soviet guns in this era. His name was Roger Marsh, a gunsmith, gun writer and NRA member from Hudson, Ohio. In 1950, Marsh researched, wrote, illustrated and self-published “Weapons I: Overture to Aggression.”

Githens mentions Marsh’s soft-cover book in his article, calling the work “excellent” and “brief but meaty.” Those are accurate descriptions, and “Weapons I” also provides a valuable snapshot of what we knew (and should have shared with our troops) about Soviet-made small arms as the Korean War began. Along with the details he shares in his book, Marsh also provides some interesting editorial:

“Although there has been little reported on the subject, it is rumored that the North Koreans have held classes for their men in the use of U.S. weapons. Its logical: Communist activists are expected to know the use of their own weapons and those of their enemies, and the North Koreans found added incentive in the fact that they expected to have a quick brawl with U.S.-armed South Korea.

I wonder if U.S. forces are getting comparable instruction in the use of Soviet and other foreign equipment? The Germans were publishing extensive information on Soviet weapons in 1941-1943, and it is 1950 now. In 1943, in the Armorers Section, ORTC (Aberdeen Proving Ground), I set up, wrote the lessons plan for and the instructional materials for, and repaired or rebuilt the material for and trained other instructors for a Foreign Material course. Maybe it saved some American lives…we did the best we could. The services have had a seven-year start anyway. I hope they have done something with it.”

Opponents Old and New

When the Chinese joined the fight in Korea, American troops would find their opponents armed with wide variety of small arms. Some were made in the Soviet Union, others were repurposed Japanese arms captured in China during World War II and finally, there were American-made rifles, SMGs and machine guns provided to Nationalist China via Lend-Lease and then absorbed into the Chinese Communist Army after China’s civil war.

The 1953 U.S. Army Military Intelligence Guidebook “Material in the Hands of or Possibly Available to the Communist Forces in the Far East” lists the following Japanese small arms potentially in the hands of North Korean or Chinese Communist troops:

- Type 14 pistol (8 mm Nambu)

- Type 94 pistol (8 mm Nambu)

- Type 38 rifle (6.5x50 mm)

- Type 99 rifle (7.7x58 mm)

- Type 96 Light Machine Gun (6.5x50 mm)

- Type 99 Light Machine Gun (7.7x58 mm)

- Type 92 Heavy Machine Gun (7.7x58 mm)

These weapons, along with the Type 89 50 mm Grenade Discharger, commonly called the “Knee Mortar”, made up the bulk of Japan’s World War II infantry weapons, all of which were captured in large numbers by the Chinese and remained in their service until the mid-1950s.

Red Impressions

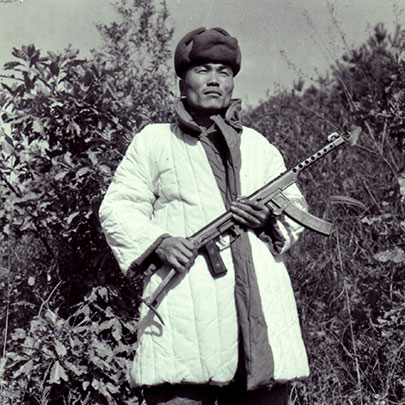

Several Soviet weapons made a significant impression on U.S. troops in Korea. During World War II, the Red Army was often short of rifles, and the Soviet remedy was to replace long arms with considerably less-expensive submachine guns, quite often at a ratio of three-to-one. Primary among these submachine guns was the PPSh-41 (7.62x25 mm Tokarev), and more than six million of them had been produced by the end of World War II.

Entire units were equipped with the PPSh-41, and with it, the Soviets introduced the idea of tremendous infantry firepower, albeit at short range, to combat on the Eastern Front. They shared the PPSh-41 with their satellite states, and licensed copies were created in North Korea (the Type 49) and China (the Type 50).

The PPSh-41 and its clones feature a high cyclic rate, 900 to 1,000 rounds-per-minute. Equipped with either a 71-round drum (the Russian and North Korean models accept the drum) or a 35-round box magazine (the Chinese version only accepts the box magazine), the PPSh spits out a lot of lead in a hurry. When Communist troops closed the range in Korea, the PPSh submachine guns gave them an advantage in firepower. G.I.s called it the “burp gun”, and some U.S. infantry commanders considered the PPSh-41 to be the best short-range infantry weapon of the war.

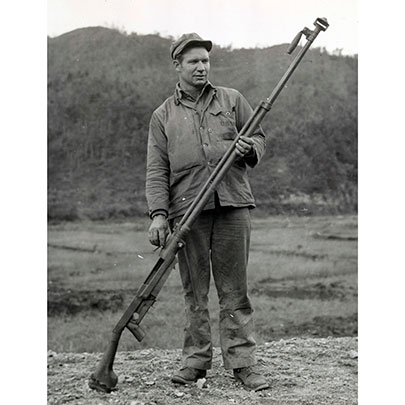

No Communist weapon brought forth as much curiosity from American troops as the Soviet PTRD-41 and PTRS-41 anti-tank rifles, chambered in 14.5x114 mm. These massive rifles, 79.5” for the PTRD and 83” for the PTRS, overlooked or considered obsolete in the West for a decade, made a big impression on American troops in Korea. What the G.I.s called “Buffalo Rifles” had been the Red Army’s prime man-portable anti-tank weapon of World War II.

The Western Allies had given up on anti-tank rifles by the end of 1941, but the Soviets had effectively used their 14.5 mm AT rifles until the end of the war. While other nations assumed that for an anti-tank weapon to be worthwhile it must be able to penetrate the enemy tank’s armor where it is the thickest, the Soviets employed their anti-tank rifles to target sensitive points like running gear, vision ports, engine compartments and even cannon barrels.

AT rifles were deployed in depth, with multiple weapons firing at a vehicle from several angles. Once disabled, the tank was vulnerable to roving Soviet tank-hunter teams. As World War II progressed, the Red Army found useful secondary applications for their PTRD and PTRS rifles, most notably in sniping at hardened enemy machine gun and artillery positions. The big rifles, along with their doctrine for use, were provided to the North Korean and Chinese Communist armies.

Interviews with North Korean P.O.W.s revealed that they were well aware that their anti-tank rifles could not penetrate the frontal armor of U.N. tanks, and thus, Communist AT rifle teams targeted lightly armored vehicles and motor transports, along with machine-gun bunkers and artillery positions. The enemy “Buffalo Rifles” drew attention for their potential as big-bore sniper rifles.

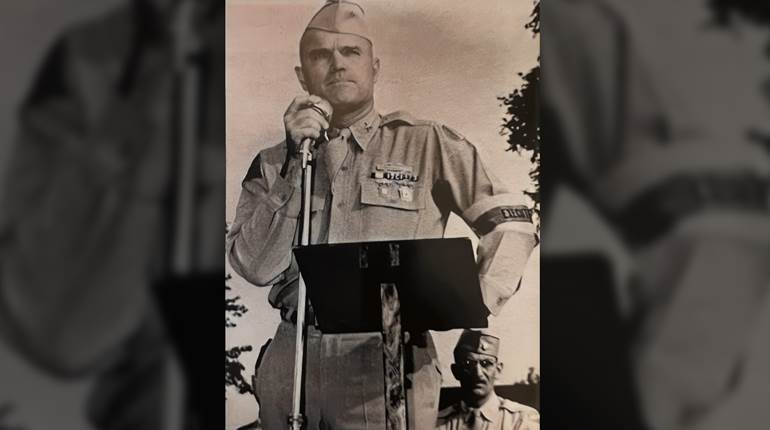

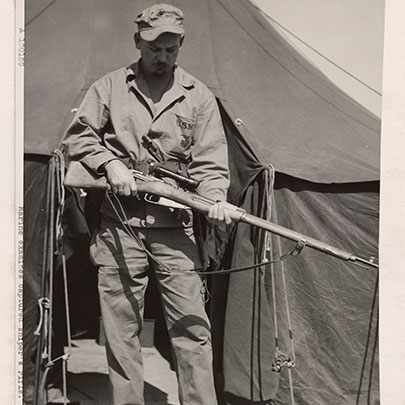

American sniping expert, Lt. Col. William S. Brophy took a captured PTRD-41 AT rifle and reworked the weapon with a .50-caliber machine gun barrel, adding a Unertl scope and the small comfort of a butt pad. Using his early conversion, Brophy successfully engaged enemy targets at more than 1,000 yds. This basic modification became one of the forerunners of the modern .50-caliber sniper rifles we know today.

Roger Marsh describes the Russian-made AT rifles in his book “Weapons I”:

“No US weapon or class of weapons corresponds exactly to the PTRD/PTRS class. The closest approximation is the M2 Caliber .50 Heavy-Barrel Browning machine gun.

Unquestionably, as far as general effectiveness is concerned, the high rate of fire of the M2 makes up for the differences in ammunition and weight, but is it impossible that a weapon of the PTRD/PTRS class might be of use in U.S. service? The PTRD weapon is surprisingly light for a weapon which can punch a hole in 30 mm thick armor at 100 meters. Perhaps an American version of the 33-lbs. PTRD type would be useful where the M2 could not readily be carried, but where a weapon effective against medium armor and motor transport might be useful, as, for example, in a behind-enemy-lines raid on supply facilities and motor pools.”

The Soviets also provided the Mosin-Nagant M1891/30 rifle (7.62x54 mm R) to their Communist allies. Chinese and North Korean snipers used these weapons, either in their standard configuration or equipped with a 3.5X PU scope. As the Korean War became a stalemate during the final two years of the conflict, snipers on both sides of the lines took their bitter toll of unwary opponents.

Soviet-made machine guns made a strong impression on the Korean battlefield as well. The venerable Maxim M1910 water-cooled machine gun was already a veteran of two world wars by 1950. Many of these were attached to the wheeled Sokolov mount, a low-profile configuration often fitted with a light armored gun shield. World War II models of the Maxim gun had a radiator cap added to the top of the water jacket, allowing snow to be easily added to keep the barrel cool.

G.I.s came to respect the light DP-27 “Degtyaryov” machine gun (7.62x54 mm R), which featured an odd 47-round pan-shaped magazine. Somewhat comparable to the BAR, the DP-27 weighed in at about 25 lbs. loaded and provided the base of fire for better units of the Chinese Army. Communist forces also used the Soviet SG-43 medium machine gun (7.62x54 mm R), and this more modern Soviet machine gun was new to American troops, apparently. Roger Marsh makes mention of this in his “Weapons 2” (1952):

“The SG-43 "Goryunov”: The Goryunov is now almost 10 years old. It was used in World War II—extensively. And yet, when the Korean Incident began, the Goryunov came as a complete and terrible surprise, according to the newspapers. One wonders how such things can happen. We can't afford many more "surprises".

Acceptable War Trophies

It is interesting to note that the 1953 US Army Military Intelligence Guidebook “Material in the Hands of or Possibly Available to the Communist Forces in the Far East” provides a list of “Permissible War Trophies” in the Far Eastern Command. All ordnance items of Japanese, German, Chinese, Polish, Czech, Rumanian, Albanian, Hungarian and Bulgarian manufacture were considered acceptable trophies, provided they were manufactured prior to the end of World War II.

No Russian-made items were deemed acceptable war trophies, and U.S. troops were instructed to turn over any captured Soviet equipment to their superior officers. The Cold War was already hot, and U.S. Ordnance intelligence had plenty of catching up to do.