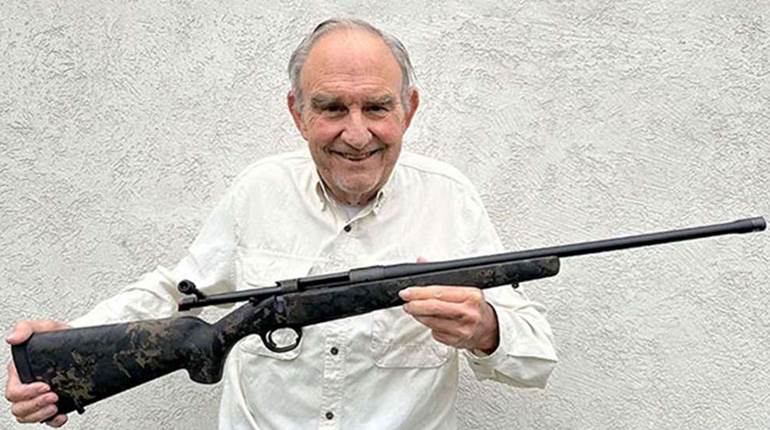

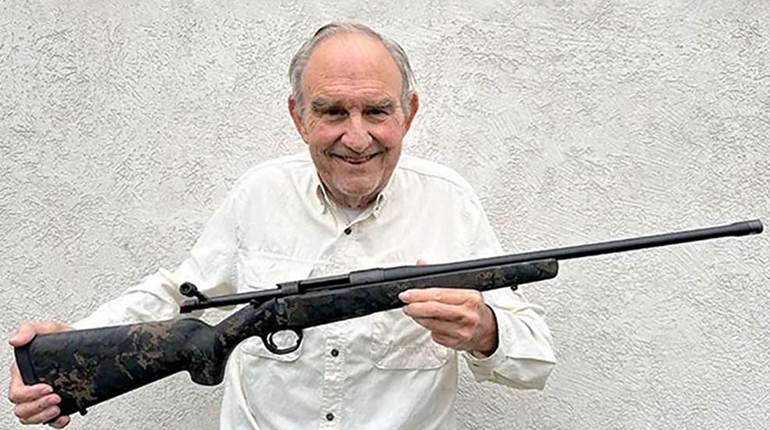

When it comes to the proper shooting technique for squeezing every bit of accuracy potential from a lightweight hunting rifle, Melvin Forbes is a master. He is also a really nice guy and is willing to share all he’s discovered since founding Ultra Light Arms (now New Ultra Light Arms) in 1986. It was Forbes’ guidance that allowed me to correct an accuracy problem that cropped up during my first encounter with a light rifle.

I worked for an optics company in those days and had borrowed what Forbes called his “loaner” for a promotional hunt. A writer who had the rifle before me was kind enough to share the results of his accuracy testing, so I knew it would shoot groups so tight they were spooky. But on my first trip to the range, the rifle shot nothing but patterns.

I called Forbes and told him the story. Do this and try that, he suggested patiently. Next afternoon, the rifle turned in three-shot, minute-of-angle (m.o.a.) groups with both factory and handloaded ammunition. More than a little pleased, I phoned Forbes with a report. He gave me some additional tips, and at the next range session several of the three-shot groups were touching. I ordered my own ULA rifle that same day.

Something like a year later, I left the employ of that optics company and joined the team at Kimber. Not long after, Kimber began manufacturing what would become a full line of lightweight rifles. The Model 84M family, designed specifically for short-action cartridges, came first, followed by the Model 8400 for the then-new Winchester Short Magnum (WSM) offerings.

Finally, the Model 84L bridged the gap by chambering standard cartridges such as the .30-’06 Sprg. Depending on action size, barrel length and stock material, these Kimber and ULA rifles weigh somewhere from just under 5 lbs. to a bit more than 6 lbs. empty and without a scope.

While quite a few Kimber models and even a handful of ULA rifles are designed for different purposes, and are therefore of more standard weight, the focus here is on techniques for shooting lightweight rifles in such a way that their true accuracy potential is realized. I’ve followed Forbes’ original guidelines and added a few of my own discoveries along the way. These steps have been shared with many shooters over the years, and those who try them often report back with news of significant accuracy improvements.

Before firing a shot, verify that the action screws, as well as those securing the mounting system, are properly tightened. Also, check that the lock ring holding the scope’s ocular lens housing in position is snug. Finally, make sure the barrel has been properly cleaned.

Since most hunting takes place during the colder months, it is important to mimic anticipated field conditions by keeping the rifle and ammunition out of the sun and as cool as possible. At the bench, stage the rifle and ammunition accordingly.

Post enough targets to cover the entire session in order to avoid trips downrange. When the range goes live, fire a fouling shot and then open the bolt so the rifle can cool to air temperature. Assuming the shot is on paper, don’t make any scope adjustments. For now, the only concern is accuracy as determined by group size; once groups are tight, adjustments for zero can be made. Most shooters seem to shoot the tightest groups when using their variable scope’s highest magnification, assuming range conditions permit, so adjust accordingly and stick with it.

While waiting for the rifle to cool, arrange the front and rear bags so that the scope’s reticle rests more or less on the anticipated point of aim. If the particular bench will allow, position yourself directly behind and squared up with the rifle, then lean forward into the rifle.

This does two important things. First, getting directly behind the rifle rather than coming in from the side provides a more consistent platform of resistance to recoil. Second, leaning into the rifle as opposed to pulling the rifle backward into the shoulder reduces arm tension, which in turn minimizes another variable. As much as the bench and seat height will allow, try to maintain a relatively straight back and neck for the same reasons.

I suspect the most common error in technique when shooting a light rifle is resting the left arm (for right-handed shooters) on the bench or using the left hand to “pinch” the rear bag. Simply put, the left hand must be used to dampen the initial effects of recoil until the bullet no longer dwells inside the barrel.

One way to accomplish this is to reach around the front rest, grip the fore-end and hold down—straight down—not down and pulling to the left. A better way may be to rest the left hand on the center of the scope with just a bit of downward pressure.

Finally, make sure to keep only light contact between the cheek and the stock. Cheek pressure, especially if inconsistent, seems to make a significant impact on how tightly those holes in the target cluster.

Once a comfortable shooting position has been established, dry fire a few times to make sure everything feels right while watching for reticle jump. If the reticle moves when the firing pin falls, practice until there is nothing more than a slight tremor.

The purpose of everything so far has been to ensure that the shooting position and technique do not apply torque or inconsistent pressure. Light rifles are more sensitive to these factors than standard-weight models.

This is as good a place as any to start an argument, but in most hunting situations the most important shot is the first one. Place that shot properly, and things generally go well from there. Often times, if a second shot is necessary then it will be taken with less time for preparation, under more stress and possibly at wounded, moving game. Even more so for a third. This suggests that cold-bore accuracy of the first shot is one of the most important things to discover at the bench.

Light rifles have thin barrels that respond more dynamically to temperature changes. Therefore, let the rifle cool with the bolt open at least three minutes between shots and at least five minutes between three-shot groups.

Additionally, it pays to record the result of each shot in a log so trends can be spotted. For instance, a rifle might drop the first two shots of each string on top of each other but open up on the third every time. Another might fire the first shot of each string through what is effectively the same hole, only to have the other shots move a bit but stay together.

Cleaning a rifle is not one of my favorite things, but most rifles perform all the better for it. Once a rifle is past the break-in period, try to clean the light ones after firing no more than four groups—it makes a difference.

One related point discovered by accident is that I tend to shoot tighter groups if I don’t change position between shots. Part of my setup ritual ensures that everything I’ll need to fire a group is easily accessible. I try never to shift my feet or even move my arms above the elbows. I also try to avoid conversation or other distractions during a string. This doesn’t seem to matter nearly as much with a heavier rifle, but I’ve noticed the difference in the groups from my lightweights over the years.

At a recent hunting convention, I visited with several people who were unhappy with the accuracy they were getting from their light rifles. It wasn’t just production models either, as some were shooting custom guns. I spent as much time as booth traffic would allow with each shooter, suggesting some things they might try. At the conclusion, I asked them to let me know how things went on their next trip to the range. I’ve heard back from about half of them, each reporting positive results.

Not surprisingly, light rifles can be pickier about ammunition than standard-weight rifles of similar quality. Both brand and bullet weight make a big difference, so it pays to consider all the options. Another issue common to light rifles is that they can be more demanding of scope and ring selection. If an accuracy problem persists, consider swapping out the scope with another that is a known performer. It might get everything back on track.

Once everything comes together at the bench, there are two important things to remember about light rifles before going afield. Sadly, I learned both the hard way. The first happened in New Zealand. I followed guide Gerald Fluerty to the top of a mountain so we could get above the bedding area of a wonderful sika deer. When Fluerty thought it was time, we moved down and caught the stag just as he was breaking cover. I sat down in the tall grass, wrapped the sling tight and squeezed off when the sight picture looked good. I heard the bullet’s whack, and the sika dropped so fast I thought he fell in a hole.

I was lucky. His head was lowered to feed, and the bullet caught him at the base of his ear—even though I was aiming behind the shoulder and had a nearly broadside presentation. At less than 90 yds., the sideways tension I was putting on the sling created stock-to-barrel contact and caused the shot to fly more than 12" off course. We skipped hunting the next morning, proved my theory on several targets and went on to take a red stag at well over 300 yds. without incident. Since then, I’ve been most careful about putting too much sling tension on light rifles, as well as standard-weight rifles with thin stocks.

The New Zealand lesson didn’t hurt all that bad, but I’m still smarting from what happened in Texas. What I suspect was the best whitetail buck I’ve ever had in my scope—certainly before and probably since—showed himself at last light. We crawled in, running out of cover some 250 yds. away from where he was feeding. I toe-pushed out of the brush, folded the bipod down, shifted forward just a bit and squeezed.

It would have been better to miss, but we found some hairs from the top of his back along with a single, and very expensive, drop of blood. Since that particular rifle is quite accurate, it wasn’t hard to prove what had happened. Too much pressure on the bipod and no downward pressure on the fore-end sent the shot high. I centered a coyote the next day at more than 400 yds., but it didn’t make me feel one bit better.

Having hunted extensively with light rifles, I now prefer them in every case where the available caliber is appropriate. With a bit of practice, they’re staggeringly accurate and blessedly easier to carry afield. While it’s difficult to imagine, a couple of pounds at the gun counter can become the weight of the world by the time you climb to the top of a mountain. Carrying a light rifle will make just about any hunt even more enjoyable.