With the passing of the solstice and onset of the new year, it is natural for many avid shooters to think about their current skills and where they might like to advance over the ‘shooting year’. Many shooters tend to build their skills in the fair weather months and mostly maintain them over the winter, so now is a natural time for some goal setting.

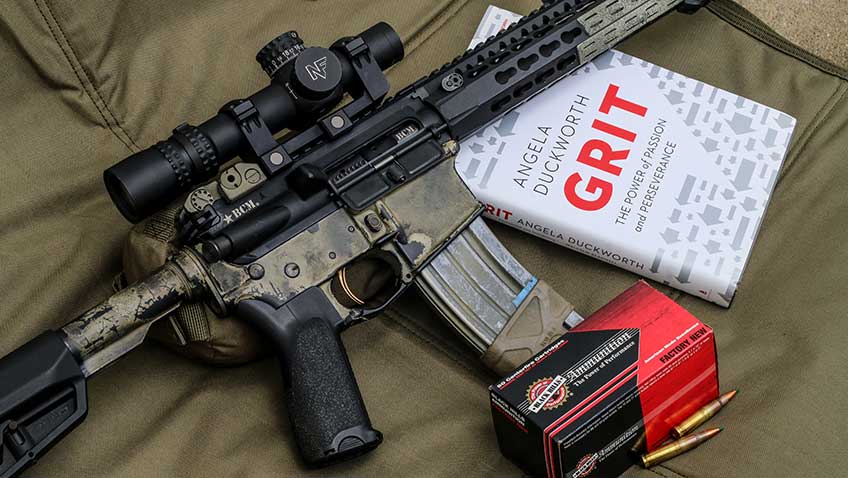

For some time, I’ve been working on a concise set of principles to guide shooters and trainers as they consider their next range/training session. After reading Angela Duckworth’s book, "Grit: The Power of Passion and Perseverance," I stopped. Ms. Duckworth’s description of ‘deliberate practice’ summarizes what I was going for beautifully and has the added benefit of being backstopped by extensive research rather than one Marine’s opinion.

Grit is a study of champions in a variety of fields; Olympic medalists, legendary coaches/teams, pinnacle musicians, etc. It is a recommended read in general, but the research into deliberate practice is especially worthwhile as a shooter ponders the kick off of the next training season. Drawing from research by Anders Ericsson, a cognitive psychologist who has extensively studied how leading experts acquired their skills, Duckworth presents the requirements for deliberate practice as:

- A clearly defined stretch goal

- Full concentration and effort

- Immediate and informative feedback

- Repetition with reflection and refinement

So, to lead with a negative…. If you and your teammates or shooting buddies show up to the range with no plan, ‘shoot around’, are lax in refacing/replacing targetry, record nothing and quickly cycle through drills if something seems hard…. You are just shooting. You may be having a great range day, but you are not training as a champion would.

I see the four elements of deliberate practice as the legs on a table, each vital to building the capability desired. However, the one that I most often see lacking in serious shooters (or high-level units with respect to shooting) is having a clearly defined stretch goal. Some may have that clearly defined goal, but it is not really aspirational, challenging and a stretch to which they are committed over time. Others may have a challenging goal, but it is so poorly defined that it can’t be broken into specific steps, skills or sub-components to guide the journey and measure progress.

The first requirement of a stretch goal is the self-confidence to believe that it can be achieved by "putting in the work." I am convinced that some shooters who have every bit of the raw capability to reach a very high skill level avoid serious stretch goals because deep down they simply cannot see themselves as "that guy." Not surprisingly, the growth profile of this crowd tends to be pretty flat.

Setting a goal with the belief that it can be achieved is the stuff of life-changing power. It can certainly boost shooting skill. In my own shooting a little less than two years ago, I shot a few rounds at an 8-inch plate at 70 yards for a project. In my mind, I viewed it as quite hard, bordering on impractical. However, some number of hits later, I changed how I perceived that shot. On the following range day, armed with an incredibly accurate 1911 (which you can read about here), my stretch goal moved from five straight hits, to a magazine of seven, to ten straight hits. At each accomplishment, the previous, almost fantastically difficult perception had fallen to the power of a stretch goal.

‘Full concentration and effort’ sounds disarmingly simple, but that is often the disciplined approach that separates shooting that contributes to skill growth and simply shooting around for enjoyment. I like to have a minor point of technique that I am intently focusing on proper ‘form’ with almost every shot. This is even the case where I am warming up or plinking around. For example, in a recent session, I was working precision handgun at distance. On some strings, I focused on follow-through, attempting to truly see the sight lift in recoil and the brass leave the ejection port. On other strings, I was intently looking for a dead-perfect, natural point of aim, sensing for any muscular pull to one side or the other as the sights settled or the pistol recoiled.

Feedback is simple in the shooting world, but it does require planning and some diligence. The easiest adaptation is to simply use more targets, reserving a single target to give feedback on a given drill or string and then replacing it. I cringe when I see shooters blasting away at a target that looks like it has been blasted by a firing squad using shotguns with buckshot. There is small chance that the shooter is getting meaningful feedback; in many cases, it is an open question if the impact is even on the target backer. With the cost of ammo, range time, etc., scrimping on targets is usually penny wise and pound foolish. On outdoor rifle lines, where it is impractical to swap targets more often, it becomes imperative to have a quality spotting scope to call the shot then plot the impacts in a data or note book as one shoots.

I keep meticulous data on my range sessions and have data books going back many years that I often refer back to. This allows me to reflect on a particular drill, or my performance with a certain rifle or pistol. The most important part after that reflection is the ability to track performance over time. With good data, a shooter can put meaning to the repetition and refinement, correlating action with results. This is a link back to the first point; the data charts the progress towards a stretch goal. As a plus, I find that the basic recording of the results makes most shooters more accountable for their performance, which in turn leads to more full concentration and effort—a virtuous cycle.

I hope you find plenty of great opportunities to not only shoot, but to set a stretch goal and get after some deliberate practice.