It seems whatever campfire I sit around these days, buddies ask: “What’s up with Remington?” I don’t pretend to know the business of producing, marketing and selling vast quantities of guns and cartridges annually, but aside from the obvious fact that Big Green has undergone its share of hardships recently, I can say this: It still makes great products. Of that I’m sure because I can tell a good gun when it’s in my hands and a bird flushes or a buck appears across a canyon.

But what of its shotguns? You never seem to hear about them in the news. Remington repeaters still dominate the upland-bird hunting, waterfowl and tactical markets because the guns work, feel great and are affordable to the masses—well that, and because there are just so many of them in Americans’ hands already. What’s more, three new Remington semi-automatics are picking up right where the Model 1100 left off.

Everyone’s Got A Remington Story

When I was but a whelp, one frosty Christmas I received a Remington 1100 Special Field LT 20 gauge with its stock shortened. Despite only being allowed to load one round into the chamber and none into the magazine for a couple years, I cut my teeth shooting that gun at everything from quail to ducks and turkeys; to this day, nothing comes up quicker to my eye or feels better in my hands than that gun or other Remingtons like it. As a matter of fact, not long ago I was at a fairly prestigious bird hunt with men carrying double guns costing as much as a sports car, and one of the guys there jokingly asked me why I was carrying a “Walmart gun to a royal wedding.” He found out why later on that evening—mainly because my four shots proved superior to his two.

Certainly, I’m biased, but I’m not alone. After all, why would millions of Americans continue to buy Remingtons if they didn’t feel the same way? In point of fact, no firm in American history has produced more models of shotguns (more than 29 lines—with many models in each line) or more shotguns in total, and the only one in the world that could exceed it is Beretta, which had about a 300-year head start on the New York company founded in Ilion in 1816.

History Of Remington Self-Loading Shotguns

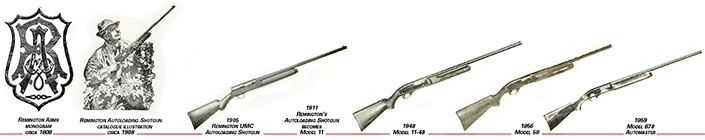

To find the complete history of Remington Arms, I suggest a sabbatical east to the National Firearms Museum in Fairfax, Va., where you should seek out curator Phil Schreier and ask him to point you toward the archives. But if you have a day job, here’s the abridged version of Remington’s shotguns, focusing on the semi-automatics. It starts almost a century after the company’s inception with the John Browning-designed Remington UMC Autoloading Shotgun in 1906, the same platform produced a few years earlier by Fabrique Nationale as the Browning A5.

By the time the autoloader was introduced, Remington had already changed hands several times. It would again in the 20th and 21st centuries. Despite those ups and downs, along with enormous events including two world wars and the Great Depression, the company was successful. Ironically, however, it owes some of that success to good ole-fashioned market competition, specifically from a company named Winchester and its venerable Model 1912 that spurred Remington to continually improve its shotguns or risk losing out to “The Perfect Repeater” each year.

Remington’s humpbacked Model 11 (the name changed in 1911) and series of pump-actions didn’t do it, although the pioneering semi-automatic had a decent run until 1948 with the release of the 11-48, which removed the hump and gave us the familiar lines of the modern semi-automatic shotgun.

A Pump Paves The Way For New Autoloaders

The pump-action Model 870 Wingmaster remedied the earlier Model 31’s flaws. It featured Model 12-like styling and fit that made it fast and intuitive for wingshooting. It was a bottom-loaded, side-eject gun that remedied jamming issues of previous models: it wore dual-action bars; its internal hammer and fire-control system were simple and robust; and it borrowed from the 11-48’s revolutionary stamped-metal mass manufacturing so the internal parts could be interchangeable and made at low cost.

The gun became so popular that by 1972 Remington had sold more than 2 million units. To date, Remington has sold more than 12 million 870s.

But I’m getting ahead of myself. What the 870 did in addition to solidifying Remington as one of the world’s top producers of shotguns was allow the company to spend a windfall of cash on R&D and advertising for new products. As a result, its excellent line of gas-operated semi-automatics, such as the 1100 series, remedied the flaws of the long-recoil-operated 11-48—much like the 870 did for the 31. In essence, the 870 began an era of shotgun dominance that inspired the name “Big Green” as the company’s logo and green-colored gun boxes became the country’s most prevalent in gun shops, department stores and under Christmas trees everywhere.

Enter The Model 1100

While the 11-48 represented a revolution in shotgun manufacturing, it was a long-recoil design modeled after the Model 11. Remington executives realized the benefits a gas-operated action offered sportsmen, and so, in 1956, it introduced the Model 58. The 3"-chambered shotgun was nice in theory and a marketer’s dream—what with its recoil-reducing action and innovative “Dial-A-Matic” magazine cap that changed the size of the gas ports based on the load chosen—but its flaws were numerous. Namely, its gas piston consumed much of the fore-end space, which limited its magazine capacity to two shells. Remington realized this flaw and almost immediately began working on an updated gun that it released in 1959. The Model 878 Automaster was somewhat of a hybrid between the 11-48, the Model 58 with its self-regulating gas system and the 870 in regard to its bolt design. But its life was also fleeting because just a few years later, in 1963, Remington released its second world-beating shotgun, the 1100.

I could write 1,100 pages on the Model 1100, whose line includes more than 25 models with multiple gauges in each, but suffice it to say that this semi-automatic engineered by Wayne Leek has sold around 4.5 million units and, at the time of this writing, has been in continuous production for 56 years. It was one of the first semi-automatics that handled like a modern shotgun—sleek-lined and well-balanced and not like a heavy, ungainly contraption. When Leek showed it to the boardroom for the first time, he said, “Gentlemen, this is the new Model 1100, and it’s going to revolutionize shotgun shooting.” He was right.

It featured, and still does, a trigger and safety group that was pinned to the receiver and could be removed easily as a unit. Its gas ports, for the first time, were located outside of the magazine tube, and this allowed it to be cleaned more easily. It was lightweight and very soft-recoiling—in fact, one of the softest-recoiling shotguns ever made. Its receiver was shallow and thin so its line in the hands was as low-profile as possible and conducive to instinctive shooting. It has been, or is currently, available in all popular gauges and in nearly all configurations for sporting, law enforcement and personal defense, including trap models, synthetics, sporting clays, upland, waterfowl, slug, tactical, etc. Historically it’s been affordable, and reliable if kept clean—something I learned the hard way from hunting with dirty 1100s. Once, after falling in fine Texas sand and relegating Big Green’s then-flagship semi-automatic to a single-shot, I learned I could disassemble the gun, including the trigger group, quickly and hose it off with a can of WD-40 and be back in action in a few minutes. I also learned to pack a couple extra O-rings as they do occasionally break.

From the 1100 stemmed the 11-87—you guessed it, in 1987—and it featured Remington’s new screw-in choke tubes among a few other features. Engineered by Leek as well, it featured a 3" chamber, RemChoke tubes and a self-regulating gas system. It was basically an 1100 without the high-gloss walnut, so Remington could sell it for a couple hundred bucks less, and it did, and still does, in droves.

In 2006, Remington launched the innovative and likely ahead-of-its-time 105 CTi (and later CTi II) with a receiver made of titanium and carbon fiber that make it extremely lightweight, yet stronger than aluminum. It was totally bilateral with its bottom loading and ejection, and while it was cool, commercially it flopped.

Of course, I’ve only hit some of the highlights here while completely skipping over some others because I must save space for the modern age of Remington autoloaders, which I believe is as revolutionary and exciting for consumers as the models of the mid-1900s were.

From the late 1990s on, the company has faced hard times. For one, there’s an Italian-shotgun company called Benelli that hammered Remington’s—and every other maker’s—shotgun sales with its excellent inertia-operated guns on which it had a patent-borne monopoly, one that has since expired. Then there are the gas-operated Berettas, and now a deluge of Turkish-made semi-automatics, too.

The Current Remington Revolution

As the shotgun editor for this publication’s sister magazine and NRA Official Journal, Shooting Illustrated, I test nearly every new scattergun that comes to market. There are plenty of great tactical shotguns, including those from FN, Winchester, Beretta, Mossberg, Benelli and others. Yet, in my mind, there is one that is the best in terms of overall performance and price right now, and that is Remington’s Versa Max Tactical.

Semi-automatics have gotten so good that if a person is not well-practiced with a pump, the semi-automatic may be more reliable, because short-stroking the slide isn’t possible. The Versa Max offers more features than any other gun out there, all in a not-crazy-expensive package that to my shoulder offers the softest recoil of any 12 gauge on the market, bar none. But it all starts with the action—and Remington’s stoutest shotgun competitor, Benelli.

Back in 1998, Benelli launched the M4 platform and then the M1014 for the U.S. military featuring its A.R.G.O. (Auto-Regulating Gas-Operating) system that utilized two short-stroke steel pistons welded to the underside of the barrel. When these pistons receive gas from the fired shell via two gas ports in the forcing cone, they slam directly against the bolt, rotating it and unlocking it before driving it rearward. From there, a recoil spring in the stock compresses and then rebounds, returning the bolt back home with a fresh shell lifted from the carrier. The gas ports are located just ahead of the fired shell, rather than way up in the barrel like most gas actions, and therefore the gas hasn’t fully expanded. Engineers say this lengthens the recoil impulse and therefore further reduces felt recoil.

Benelli released a version with four gas vents for lighter loads. So, while the A.R.G.O. was self-regulating to an extent, it wouldn’t shoot everything. Hardly any repeater, short of a pump, would.

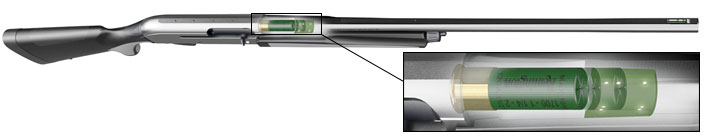

Remington latched onto the idea, only with one ingenious twist—rather than two or four ports to handle various loads, Remington’s system uses seven. But in Remington’s system the seven ports are physically regulated by the shell length itself, because they are located in the chamber. Mighty 3 1/2" shells cover all but three holes, while mid-power 3" shells leave four ports open and low-velocity, 2¾" shells leave all the ports open so maximum gas is delivered to the pistons to cycle the action. The result is an equalization effect so that each load, regardless of its power disparity, puts approximately the same force on the bolt and spring thanks to these Versaports, which serve as the gas gatekeepers. The result is a gun for sportsmen and tactical guys that can truly handle any load. As a hugely advantageous byproduct, the gas system bleeds away excess gases as well as drawing out the recoil impulse over time, both helping reduce felt recoil. I know this because I can feel it.

The Versa Max Competition Tactical’s near-8-lb. weight and stock design that features a super-soft buttpad and a gel comb insert also do wonders for taming kick. Then Remington put features 3 Gun shooters and tactical gurus demand, such as oversized controls (bolt handle, action release button and safety), a rubber-clad stock and interchangeable choke tubes. In my view, it probably has the best sights on the market—a fiber-optic front bead combined with a shallow, express-style V-notch rear give it the best of both worlds. It’s unobtrusive enough that I can shoot birds with it, but accurate enough for slugs at distance. It also copied Benelli with its magazine cutoff switch, trigger guard style and stock-adjusting shim kit. In sum, the Versa Max Competition Tactical, for under $1,400 is my favorite do-all gun on the market. It points so well and has such kind recoil that I have actually taken it to the clays range by choice. Indeed, the Versa Max action, considering its versatility, is likely the best gas-action shotgun ever invented … but Remington didn’t stop there.

In 2015, Remington released its V3 gun that utilizes the VersaPort gas system, but combines it with two shorter recoil springs that race down either side of the action, thereby eliminating the need for the recoil tube and spring inside the stock like that of the Versa Max. In essence, this gave the V3 two advantages over most gas guns. First, it moved the balance of the gun closer to the middle of the receiver, or “between the hands” as traditional wingshooters desire. Second, it gave Remington, excuse the untimely pun, stock options. After the boutique gunmaker Black Aces Tactical and then mighty Mossberg tested the waters with 14"-barreled pumps that were made from the factory with bird’s head grips and, therefore, legally defined as “firearms” and did not require an NFA stamp, Remington followed suit with its 870-based Tac 14.

But it had something that the other makers didn’t, and that was a semi-automatic in its V3 that didn’t require a full-size buttstock. Remington’s resulting V3 Tac-13 is a 13"-barreled semi-automatic that holds five rounds and measures just 26½" from barrel to grip. It is, perhaps, the perfect “firearm” for backpack, truck, boat or anywhere. I suspect Remington sells a pile of them.

The Short Answer

So, when guys in hunting camp or at a cocktail party lament the recent tribulations of Remington, the honest truth is this: America’s oldest gun company has had its share of ups and downs through the years, but, 115 years after it first started making them, Big Green still produces some of the finest repeaters made for firing shotshells—and does it at reasonable prices. Of course its rifles aren’t too shabby either, but that’s another epic story altogether.