Few international politicians ever considered the giant frozen landmass of Greenland until the early days of World War II. After Nazi Germany occupied Denmark in early April 1940, Allied nations—specifically England—became concerned the Germans might establish military bases in Greenland, the massive territory owned by Denmark.

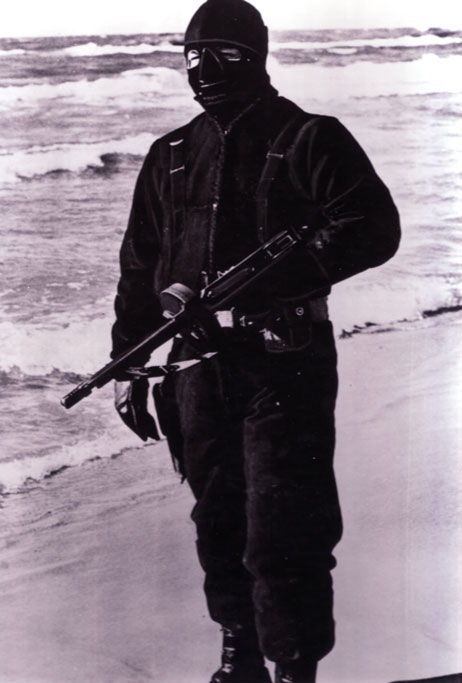

Even though neutral at that time, the United States acted quickly, and the U.S. Coast Guard cutter “Comanche” delivered the first American consul to Greenland in May 1940. The strategically important cryolite mine at Ivittuut was soon defended by a party of U.S. Coast Guardsmen, and the U.S. officially announced it would sell arms to Greenland. The .45 caliber Reising Model 50 was the most common submachine gun in use by the Coast Guard during World War II. In the background are a pair of Stevens Model 520-30 12-ga. trench guns, with M1917 bayonets attached. These were normally used for guarding prisoners.

The .45 caliber Reising Model 50 was the most common submachine gun in use by the Coast Guard during World War II. In the background are a pair of Stevens Model 520-30 12-ga. trench guns, with M1917 bayonets attached. These were normally used for guarding prisoners.

By August of 1940, the U.S. Coast Guard was conducting aerial surveys of Greenland’s west coast, while the cutter “Northland” searched the east coast for signs of German military landings. Northland found three German weather-reporting stations, and the U.S. government reported the activity to the British. The Royal Navy sent a warship to capture the German agents and eliminate the weather stations.

As the war in Europe progressed, and with more and more U-Boat activity in the North Atlantic, the United States decided to occupy Greenland on April 9, 1941. The situation escalated quickly, and a South Greenland Patrol was created in June 1941, followed by the Northeast Greenland Patrol established in July. By October, the U.S. Navy consolidated the two patrols into the Greenland Patrol of the Atlantic Fleet. By December of that year, America was at war.

A memo from Admiral Harold Stark, chief of naval operations, concisely outlined the mission of the Greenland Patrol:

The first purpose is to support the Army in establishing airfield facilities for use in ferrying aircraft to the British Isles

The second purpose is to defend Greenland and specifically prevent German operations in Northeast Greenland

Between June and September 1941, U.S. Army engineers constructed 85 buildings and several miles of access roads in the Southeast Greenland town of Narsarssuak. Jeeps were flown in and became the first automobiles ever used in Greenland. Gradually, the airfield was enlarged and improved, and the entire base became known as “BLUIE West 1.” This eventually became an invaluable strategic waypoint and refueling station for thousands of American aircraft on their way to England.

Living conditions in Greenland ranged from uncomfortably cold to unbearably cold. The barracks at BLUIE West 1 were well-constructed, sufficiently heated and even featured a movie theater. Simply existing in the arctic (even in the more benign areas of Southwest Greenland) was difficult enough, engaging in combat in those conditions was far above the call of duty.

Greenland’s position made it a perfect location for weather-reporting stations, and the Germans were quick to take advantage of the uninhabited sections of Northeast Greenland. American forces intercepted German radio transmissions as Nazi weather-reporting teams passed along information on developing weather systems to the German high command, as well as U-Boats operating in the North Atlantic.

The Greenland Sledge Patrol

As there were precious few aircraft available to scout the grand expanse of coastline, fjords, ice-flows and mountains, an alternate reconnaissance force was needed in Greenland. This became the Greenland Sledge Patrol, an experienced group of Inuit and Danish hunters recruited by the government of Greenland and equipped by the U.S. Army. These patrols used dog sleds to cover significant amounts of coastline in search of German military weather-reporting teams. The go-anywhere, do-anything sled dogs were the unsung heroes of the patrol.

Coast Guardmen of the Greenland Sledge Patrol examine captured German equipment during 1943. Most of them carry the M1903 Springfield rifle. The officer to the left carries an M1911 pistol.

The technological backbone of the Sledge Patrol was the U.S. Coast Guard cutter “Northland” (WPG-49). The “Northland” was capable as an icebreaker and was also equipped with powerful radios, plus a pair of Danish-speaking interpreters on board.

In early September 1941, men of the Sledge Patrol spotted an unidentified group making camp near Franz Joseph fjord. The Northland was contacted, and on Sept. 12, the Coast Guard men found a fishing trawler, the “Buskoe” (flying Norwegian colors) in MacKensie Bay. When Buskoe was boarded and searched, high-powered radio gear was discovered aboard what was supposed to be a simple fishing vessel. Questioning of the Buskoe’s crew established that they had recently dropped off a group of Germans with a radio transmitter. That night, an armed party drawn from the Northland’s crew went ashore and surprised three German radio operators in a radio shack disguised as a hunting camp. The Germans and their equipment (including a codebook) were taken into custody and all were ultimately sent to the U.S. for internment.

This Coast Guard BAR man seems unimpressed with what is normally considered a beautiful day in Greenland.

The Sledge Patrol was also effective in rescuing Allied airmen that had force-landed along Greenland’s icy coast. Over time, Coast Guardsmen were landed to install shore markers, LORAN radio beacons and other navigational aids. In November 1942, the “Northland” put ashore a team of 40 men with equipment to build a high-frequency direction finding station.

None of these actions made headlines in wartime newspapers otherwise filled with the exploits of Allied troops at war. But quietly, America’s ability to control Greenland was a deciding factor in the naval war in the Atlantic, the supply of aircraft for the air war in Europe, and the overwhelming logistical superiority that American forces eventually enjoyed in the European Theatre of Operations.

At war in the Arctic

As the war began to turn against Germany, their attempts to gain access to Greenland for accurate weather reporting became more frequent and more desperate. Following D-Day in June 1944, but before the Battle of the Bulge in December, the U.S. Coast Guard captured more than 60 Germans and eliminated several Nazi weather stations on Greenland’s northeastern coast.

During this time, the German weather ship “Externsteine” was captured and two other German ships in the area were destroyed. “Externsteine” was discovered trapped in the ice, attacked and boarded by the Coast Guard cutter “Eastwind”. “Eastwind’s” prize crew kept the German naval officers on board as insurance while the “Externsteine’s” scuttling charges were disabled. Ultimately, “Externsteine” was the only enemy surface vessel captured by American naval forces during the war.

Combat casualties were light on the frozen fjords and ice-flows. The Coast Guardsmens ability to endure the unbelievably harsh conditions proved to be their greatest weapon. When caught in the crosshair, most Germans serving in Greenland chose to surrender rather than die in a frozen hell.

![Auto[47]](/media/121jogez/auto-47.jpg?anchor=center&mode=crop&width=770&height=430&rnd=134090788010670000&quality=60)