The wide variety of Jarrett rifles include this Beanfield model in 7 mm STW in a McMillan wood-grain fiberglass stock and the .300 Win. Mag. Wind Walker evaluated by the author and built on Jarrett’s proprietary Tri-Lock action.

Farming was Kenny Jarrett’s ambition as a youngster, and, while he went on to great success as a man of the soil, he is better-known around the world as a builder of big-game rifles capable of uncommon levels of accuracy. That part of the story begins during a time when hunters in the Southeast spent most of their hours seeking deer in heavily wooded areas. When it was discovered that more could be spotted by watching over vast cultivated fields from tree stands and other elevated positions, the typical shot suddenly grew from inside 100 short paces to several hundred yards away. The Winchester 94s and Marlin 336s that had long served as faithful venison harvesters suddenly became short on both accuracy and reach.

At the time, Jarrett was working on a farm owned by an uncle, and, in order to supplement income needed for a growing family, he began a second career in general gunsmithing. Repair work out of an old building in his backyard used up most of what little spare time there was to devote to the business, but he eventually got around to seeking ways to improve the accuracy of factory rifles. That led to a desire to build even more accurate rifles from scratch, and benchrest competition held the answers he was looking for.

The technical information needed might have been acquired by simply asking a lot of questions of gunsmiths who were specializing in building super-accurate rifles for benchrest shooting, and several are credited with being quite helpful along the way. But Jarrett learned by becoming one of the top competitors in the country, first while using rifles built by others and later with rifles he built himself in his own shop. A walking encyclopedia on the American Civil War, his museum on the Cowden Plantation houses an impressive collection of artifacts from that conflict. In another room you will find a couple of walls filled with awards from his benchrest shooting days.

Among other important things, Jarrett learned that the keys to building a rifle capable of setting new records and winning matches were absolute dimensional uniformity combined with perfect alignment and concentricity among component parts. By utilizing the materials and technical skills required in putting together a heavy benchrest rifle, a lighter rifle more suitable for hunting use, yet capable of closely approaching its accuracy, could be built. And it could be accomplished on a consistent basis.

In 1979, he began to apply what he had learned by replacing the barrel of a Remington Model 600 rifle with a benchrest-grade barrel made by Clyde Hart. That was several years before the fiberglass stock became popular outside of benchrest shooting circles, so the barreled action was glass-bedded in the factory stock. The barrel, chambered to .243 Ackley Improved, consistently shot the 85-gr. Nosler Partition inside one-half minute-of-angle. The first deer taken just happened to be standing on the far side of a soybean field, and so was born the Beanfield Rifle.

Jarrett Rifles is still in the original building, but growth has required several expansions over the years. The old test range is still in use, but running alongside it now is a 100-yd. indoor range. Take a few steps back and you enter a spacious reloading room where ammunition is made. Another range a couple of miles down the road has a smaller reloading room along with several covered shooting benches. A wheeled target board pulled by a golf cart is easily positioned at 100-yd. increments out to 1,000 yds.

The original lathe used for re-barreling rifles is still in the shop, but it is now accompanied by several CNC machining centers. Barrels, as well as Jarrett’s own action, are made in-house. Same goes for Kevlar-reinforced, fiberglass stocks—although stocks made by McMillan are used on special-order guns, such as those in .450 Rigby and .50 BMG.

Of the operations observed there, the making of receivers for the Tri-Lock action may be the most interesting. Made in short and long versions, as well as a left-hand version of the latter, it starts with a bar of 15-5 stainless steel. After all exterior machining is completed, wire EDM machining is used to precisely bring the inside of the receiver to the desired dimensions and shape. That includes raceways for the bolt’s three locking lugs.

The interior profile of the receiver ends up matching that of the bolt head, so the next step is to form the locking lug seats inside the receiver ring by line-boring from the front with CNC machining. It is not unusual for the locking lugs on a factory rifle to make only partial contact with their seats in the receiver. The worst-case scenario will have only one of a pair making any contact at all. Due to more precise machining, all three locking lugs of the Tri-Lock action make 100 percent contact. That is in lieu of squaring and lapping the locking lugs as is commonly done when gunsmiths perform so-called blueprinting jobs on mass-produced actions.

The bolt has an AR-15/M16-style extractor and a plunger-style ejector, the latter with a big difference. The commonly seen ejector of this type tries to push a chambered round out of alignment with the bore by exerting pressure on one side of the cartridge head. The ejector in the Tri-Lock bolt is not spring-loaded and exerts no pressure on a cartridge or fired case until it is out of the chamber and in the final stage of ejection. Jarrett describes it as “controlled ejection.” Wobble during bolt travel is virtually eliminated by a close fit between the locking lugs and their raceways in the receiver, and by attaching a close-fitting steel sleeve to the body of the bolt. As the bolt is inserted into the receiver, the sleeve is retained by a shoulder inside the receiver bridge.

Another interesting feature of the Tri-Lock receiver is its interchangeable feed rail system. Machined separately and then attached to the receiver, the feed rails are sized specifically for various families of cartridges and, in some cases, for a specific cartridge.

The same 15-5 stainless steel used in manufacturing actions is also used in making barrels. Purchased from a foundry in Germany, the cost is considerably more than the same type of steel available domestically, but according to Jarrett, lot-to-lot hardness is more consistent. After a barrel blank is trued on the outside it is drilled, reamed twice for smoothness and then rifled by the button process. From there it undergoes heat treatment and is then hand-lapped.

The benefit of hand-lapping the bore of a barrel is often misunderstood. Heat-treating a barrel upsets its bore and groove diameter uniformity. Not by much and not enough to matter in mass-produced factory barrels, but it is enough to make a big difference in barrels expected to consistently deliver less than half-minute-of-angle (m.o.a) accuracy. Rifling a barrel with its bore and groove diameters a bit undersized and then hand-lapping to the desired diameters improves uniformity from one end of the barrel to the other. Jarrett guarantees a deviation no greater than 0.0001" from chamber to muzzle. To put that into perspective, the cover page of American Rifleman is 0.003" thick, and if you sliced it into 30 layers of equal thickness, one layer would measure the same as the maximum end-to-end bore and groove diameter variation of a Jarrett barrel. Another important benefit of properly hand-lapping a barrel is the almost total elimination of copper fouling.

Making precision barrels is quite labor-intensive (the lapping alone can take up to four hours), but it pays off. The accuracy guarantee of a Jarrett rifle has long been 0.50" for three shots at 100 yds. for .30 caliber and smaller, and 0.70" for larger calibers. Based on my experience with a number of rifles in various calibers through the years, those figures are quite conservative.

Jarrett is located only a few hours away from my home, and during the 1980s and 1990s I hunted deer on his farm several times each year. Hunting over soybean fields is best done during the afternoon, and since the shop is conveniently located at the edge of the farm, I often spent the morning hours accuracy-testing rifles prior to their shipment to customers all over the country. As was and still is customary, groups fired with the rifle, data for the load used and 20 loaded rounds were included in the package.

Some rifles required a bit more load development than others, but, of all the rifles I tested, I can recall only one that absolutely refused to consistently shoot three bullets inside half-an-inch at 100 yds. Built on a Remington 700 action, after its barrel had been replaced twice to no avail, Jarrett calmly clamped the rifle into a band saw and sawed it in half, right down through its action.

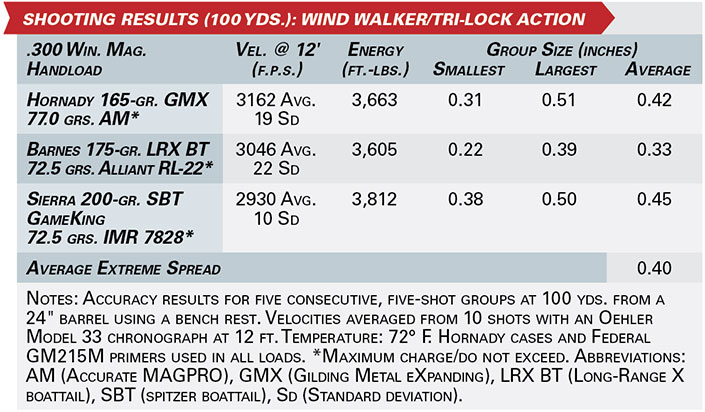

The rifles I have shot were not limited to small calibers. Those chambered for cartridges such as the .338 Win. Mag. and .375 H&H Mag. also averaged less than half an inch. Perhaps the biggest surprise came while shooting a rifle in .416 Rem. Mag.; it averaged 0.42" for five, three-shot groups with the Swift 400-gr. A-Frame. The most accurate rifle chambered for a big cartridge was in .338 Lapua Mag. Its average, for the few groups fired at 100 yds., was 0.25" with the smallest and largest groups measuring 0.15" and 0.38", respectively. At 500 yds., the best five-group averages with the Barnes 280-gr. LRX and Sierra 250-gr. GameKing were 2.03" and 2.17". That from a big-game rifle weighing 8 lbs., 8 ozs., without scope. The difference in three-shot and five-shot accuracy with a Jarrett rifle will vary depending on barrel weight and the cartridge being fired, but I usually find it to be less than 20 percent. Quite often it is considerably less.

Do we actually need big-game rifles capable of such high levels of accuracy? The answer from a practical point of view is no. I shot my first deer back when many hunters considered a rifle capable of 2" accuracy at 100 yds. plenty accurate, and I don’t recall missing the target because my rifle was not accurate enough to hit it. But I do believe an accurate rifle instills confidence in a hunter, and that can result in more clean kills on big game.

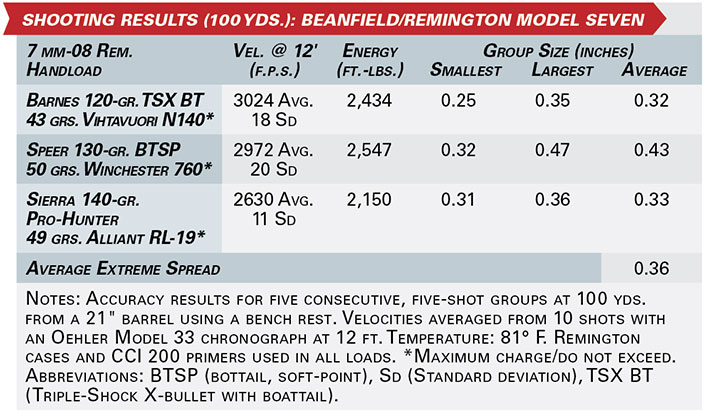

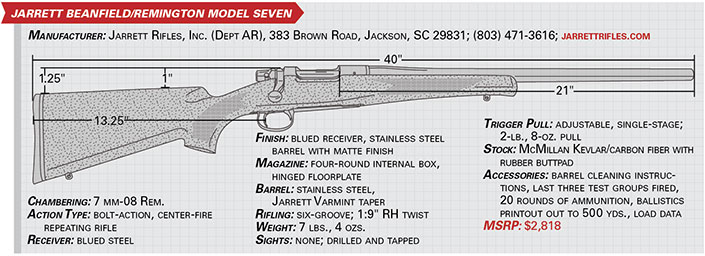

The original Beanfield Rifle built on a customer-furnished action is still available. My 1980s version in 7 mm STW on a Model 700 action is fairly typical of those built through the years. Its medium-weight, 25" barrel measures 0.700" at the muzzle. Overall weight with a Zeiss 3-9X Diavari V scope in a Talley mount is a couple ounces over 9 lbs. The factory trigger was tuned to a smooth 33 ozs. with no detectable creep or overtravel. Several barrel contours are available today, as are a dozen or so stock colors. The Remington 700 continues to be the most commonly used action, although quite a few are built on Jarrett’s Tri-Lock action as well as Remington’s Model Seven and Model 600 actions, and the Winchester Model 70. Many factory and wildcat chamberings are offered.

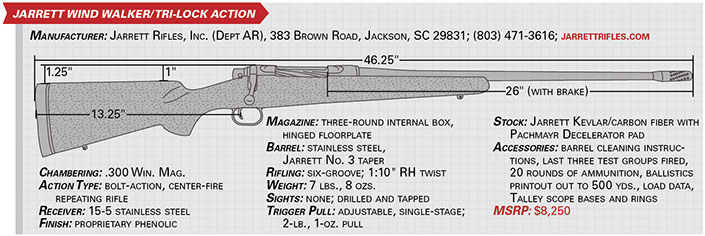

Other models, all built around Jarrett’s Tri-Lock action, start with the Wind Walker. At a weight of 7 lbs., ounces are trimmed away by the use of a blind magazine and a fairly light, 24" barrel. Like all models, it comes with or without a muzzle brake and with Talley scope rings and bases attached.

Add a hinged magazine floorplate and a slightly heavier 24" barrel with a No. 3 contour and you have the Ridge Walker at 8 lbs. Stock composition is 60 percent Kevlar and 40 percent fiberglass, and it has the same trim lines as the Wind Walker stock. The Signature version of this model has a stock of fancy English walnut and is built to customer specifications. The stock can be in classical or California styling with the grade of wood and checkering patterns to suit. Metal engraving ranges from elaborate to nothing more than the owner’s initials on the floorplate. All rifles built on the Tri-Lock action have a Jewell or Shilen trigger.

The Long Ranger does not come with ammunition loaded with silver bullets, but it is available in two versions. Both are on single-shot versions of the Tri-Lock action. The target version weighs around 10 lbs. without scope and has a 27" barrel with a varmint taper. Rifling twist rate depends on the chambering. The 1:9" twist of a barrel in .300 Jarrett is quick enough to stabilize the longest available bullets of its caliber. Weight of the hunting version is reduced to 8 lbs. or so by the use of a lighter 26" barrel with a No. 4 contour, and by utilizing the same stock as used on the Ridge Walker. The quick rifling twist rate just begs for the use of the new crop of long-for-caliber bullets such as the Barnes LRX and Nosler AccuBond LR.

As its name implies, the Professional Hunter was designed with Africa in mind, although it is equally suited for a brown bear hunt in Alaska’s rain forests. Its quick-detachable Talley scope mount makes for easy access to open sights consisting of a quarter rib-attached leaf at the rear and a large ramped white- or gold-colored bead up front. The rifle comes with its sight regulated at 50 yds. with whatever load the customer prefers. Like all models, the metal has Jarrett’s proprietary phenolic metal finish which is available in several colorations (black and gray are the most popular). The most frequently requested chamberings are .375 H&H Mag. and .416 Rem. Mag. The Professional Hunter is also available with a stock of American or English walnut.

Those are standard offerings available on fairly short delivery but one-of-kind custom jobs limited only by the imagination of a customer are also available. All Jarrett rifles come with a simple guarantee. Try one for 30 days and if not completely satisfied, return it for a full refund.

Whereas Jarrett Rifles began as a one-man operation it is now a family affair. Son Jay is in charge of production while another son, Cain, heads up the barrel operation. Daughter Rissa handles everything from keeping everyone straight to shipping rifles to customers all over the world. But Kenny Jarrett is still involved on a daily basis, and no rifle departs the shop before receiving his personal stamp of approval.

And, as far as I know, he hasn’t had to put an action through the band saw in quite some time.

Shooting Three Great Beanfield Rifles

Upon receiving an invitation to hunt deer on Kenny Jarrett’s farm in October 2014, I immediately knew that I would take along the Beanfield Rifle he built for me on a Remington Model 700 action in 1987. The first rifle chambered for the 7 mm STW cartridge, it still has its original barrel. I have not kept an accurate record of the number of rounds fired in the rifle during the past 27 years, but I can say it has accounted for a lot of game, including a record-book interior grizzly in Alaska in 2010. No handloads for the rifle were on the shelf, so I took along a box of custom ammunition loaded by Nosler with the 140-gr. AccuBond bullet.

During my visit I also hunted with the first Beanfield Rifle built by Jarrett in 1979. As mentioned earlier, it is chambered in .243 Ackley Imp. and on a Remington Model 600 action. Judging by its appearance, it has to be the most-used rifle I have ever taken to the field. Fresh from its third re-barrel job, the latest barrel had been installed several weeks prior to my arrival. It suddenly dawned on me that I had a rare opportunity to shoot groups on paper with three great Jarrett rifles built over the past 35 years. To round out the trio, I shot a recently completed rifle in .300 Jarrett built around his Tri-Lock action.

Two of the rifles belonged to him, so, for the moment at least, I strayed from the standard five-shots-per-group protocol at American Rifleman by shooting three-shot groups at 100 yds.

Two of the rifles belonged to him, so, for the moment at least, I strayed from the standard five-shots-per-group protocol at American Rifleman by shooting three-shot groups at 100 yds.

In order to become familiar with the triggers of his two rifles, I dry-fired them several times prior to punching paper. A single group fired with each of the rifles measured 0.287" (.243 Ackley Imp.), 0.367" (.300 Jarrett) and 0.438" (7 mm STW). Daylight was rapidly draining from the day, and the deer had started moving, so additional shots at paper targets would have to wait.