This article was first published in American Rifleman, Sept. 2009

After many more days of glassing from our elevated lookout spots in East Africa’s Frontier District, I felt pretty sure we’d seen every elephant in the area, and there was no sign of the grand old bull groups we’d hoped to find. They were obviously somewhere else, and so we returned to camp to make another plan. The time had come to move on to new country, and I gave instructions to the staff to assemble a light fly camp along with some provisions to last a couple of weeks away from our base camp.

Early the next morning, after loading camp equipment and provisions on the camels, we bid farewell to the men who would remain at base camp and set off into the unknown. The hunting party, comprised of Bob and myself together with the trackers and grooms, mounted up while the rest of the crew walked with the camels some distance to the rear. Setting off for new country we felt as free as the wind.

We skirted the foothills of the brooding Matthews range for most of that day trying to steer clear of thick bush as much as possible in order to avoid disturbing any rhinos that might be laid up in the shade. To draw the charge of an enraged rhino was the last thing we wanted. Leaving the shady bush to the rhinos, the sun beat down on us mercilessly. We saw few elephant, but marveled at how trusting other game—Oryx Beisa, Gerenuk, Grant’s Gazelle, Grevy’s Zebra, Lesser Kudu and Reticulated Giraffe—were of our caravan, obviously at ease with the Samburu livestock. Dainty little Dik Dik darted from one shrub to another sometimes passing between our lines of animals.

We potted a few guinea fowl and spur-fowl with the Browning .22 rifle (see sidebar on p. 71) that I’d brought along for that purpose, and when passing through an area where elephant were unlikely to be, Bob shot a Grant’s gazelle for the staff. To avoid disturbing the area while hunting elephant, we restricted ourselves to shooting at only camp meat and a few birds for our diet.

By mid-afternoon our caravan reached Irere, a dry river bed reputed by the Samburu to be favored by old elephant bulls. There the men cut bush and built a strong boma (thorn-bush fence), more to keep our animals from straying at night than to keep any predators out. Our little fly camp was very basic and set up next to the boma. It was amazing how comfortable our little fly camp was, yet skilled safari hands packed only the essentials transported on the backs of camels. We remained at Irere for several days without finding even an old track of the supposed huge tuskers reputed to live there. It was the same old story, with the presence of mostly breeding herds, and not even that many of them in this new area.

But, the nights under a canopy of stars were absolutely enchanting. Occasionally I’d wake to the sound of contented camels chewing their cud or the odd protesting snarl from one of them. Sometimes we’d hear the giggles of prowling hyenas, occasionally the raucous bray of a Grevy’s zebra stallion announcing to every lion within hearing distance where to find him, the scream of an elephant somewhere out in the bush, the distant roar of a lion, and my Lord, how some of our retinue could snore.

Given the lack of fresh bull sign, within a day or so we decided to move on to Ngoronit, another watering place located farther along the mountain range. As our caravan moved single-file along a high bank with a sharp drop to the surface of a dry, sandy riverbed below, a sudden scream came from the bush on the opposite side. An enraged young elephant bull charged straight at us from across the sandy riverbed, trumpeting furiously. Startled, we all spurred our mounts on, but Bob’s horse responded by suddenly lying down, and Bob hurriedly walked off over its head. The whole caravan was thrown into utter confusion, with the camel handlers desperately trying to restrain their excited charges. Seeing Bob’s ludicrous predicament, I snatched my rifle from its scabbard and slid from the saddle ready to use it if absolutely necessary. Fortunately the bank proved too high for the bull, and it turned away still screaming and trumpeting, head and tail held high, and returned from whence it had come.

In the meantime, a few hearty jerks on the bridle brought Bob’s mount back to its feet, and presently, our crew got the camels calmed down again and we continued on our way. We had a good laugh thinking back to Bob’s predicament, especially when he suggested that maybe it would have been better if he’d just picked up his horse and carried him. I can only attribute the strange behavior of Bob’s horse to assuming an “attitude of submission.” Similar behavior was recorded by Frederick Selous, the great hunter and naturalist, who mentions being chased once by an elephant while on horseback. Suddenly the horse stopped dead in its tracks, and to save himself Selous jumped off and hid in the bush. He watched the elephant come right up to the horse, touch it all over with its trunk, and then without hurting it in any way, move off. It’s hard to say what motivates a horse sometimes.

For days we combed the bush around Ngoronit, and again sat for hours on hillsides glassing the surrounding country. It now seemed we were seeing fewer and fewer elephants, and the thought that maybe, just maybe, that hundred-pounder might elude us, began to sink in. Those long white tusks, which had been within our grasp early on, began to get longer and thicker by the day in my mind, and probably Bob’s as well. But to both of our credit, neither of us said out loud that maybe we should have taken the bull. Time was running out, and we still had a three-day trek back to base camp to consider. I knew my crew was also beginning to consider that if we didn’t get that big elephant the Bwana wanted so badly—maybe he might not be so generous with the tip at the end of the safari!

Then one day a Samburu moran (warrior), resplendent in his “red-ochre-mixed-with-sheep-fat” paint and glistening with perspiration, strolled nonchalantly into camp carrying his two, long razor-sharp spears. Even before greetings was exchanged the crew were pressing him about whether he’d seen any big elephants.

“Yes,” he said.

“Where?”

“At a place called Illaut—half-a-day’s journey from here,” he replied. “There were many elephants at Illaut, but when the rains fell in other places, none fell there. All the elephants left except two—one very old bull with big tusks who has lived there for many years, and the other, a young askari (guard) bull, with him.”

With increasing interest, we asked when had he last seen them.

“Yesterday,” he replied, “but when I saw the old one he was alone. I think the young elephant has left. There is no food for elephants at Illaut.”

“Let’s go,” I said to Bob. “It’s our last chance, unless a miracle happens and a hundred-pounder walks into camp.”

In short order we broke camp, our camels were brought in, loaded, and we were off to Illaut—four hours away under the relentless “big-eye” of the sun. Arriving there just before sundown we soon had our camp set up and settled in for the night. A Somali shopkeeper, who ran a small duka (shop) nearby, confirmed that, indeed, an old elephant with big tusks drank at the wells each night. He told us that until recently there’d been two bulls, but the younger one must have moved on. We went to bed impatient for the morning.

At first light our lads were at the wells looking for tracks, and reported back that a bull elephant had visited the wells during the night. We ate a hasty breakfast while the horses were being saddled and were about to start tracking when Areng, the head groom, suddenly appeared, almost dragging a young Samburu girl along behind him.

“This young girl says she’s just seen the elephant while she was bringing goats to the water,” he told us excitedly.

“Where?” I asked. The young girl pointed with her wire-ringed arm toward a not-too-distant low ridge.

“She says the elephant is behind that ridge,” Areng added.

Mounting up, we soon arrived at the low ridge the girl had indicated. As we crested the ridge, there it was, standing on the top of the next ridge, perhaps 400 yds. distant. The bull stood on open, barren ground, and everything from his toenails to the top of its head was visible. Even without binoculars its dark-stained tusks were spectacular, reaching nearly to the ground and thick in girth. It dominated the scene and like a dream-come-true, was what we’d been searching for during the previous three weeks.

We quickly dismounted and left the horses with a groom while we walked up to within about 30 yds. of the big bull. The bull stood very still, with only the tip of the trunk moving slightly as it breathed in and out. It was obviously old, very old, its body shrunken and its hide mossy and barnacled with age, and perhaps it was sleeping as we watched. Only those superb tusks indicated what a magnificent bull it had once been. It was now alone and slowly starving. The herds, many of them perhaps the bull’s own offspring, were the first to move to greener pastures and finally even its askari, possibly a son, was forced to leave owing to lack of food.

I whispered to Bob, “A hundred pounds plus for sure, go ahead, take him.” Bob brought the double to his shoulder and fired twice, and the old bull faltered then crashed down and lay very still.

We approached cautiously, but the bull was dead, and the men were jubilant, laying their forearms along the tusks in the traditional method of measurement while heaping congratulations on Bob.

Our objective, a hundred-pounder, had been achieved and our time in the area was nearly exhausted, so we busied ourselves with the picture-taking. After we finished, old Katunga, an artist with skinning knife and axe, proceeded to remove the fine pair of tusks ever so carefully.

We rewarded the Samburu girl with some shillings for having indicated to us where she’d seen the elephant, which possibly saved us hours of tracking in that hot, dry, rocky country. We celebrated quietly that night beside our small campfire and agreed that it had been a good safari. During the hunt we had excitement, frustration and some good laughs. It had also been a totally new experience for us both, to be in truly wild country and no closer than three-day’s march from the nearest set of wheels. We’d achieved our objective, albeit by the skin of our teeth, but that added to the satisfaction we now felt.

We left Illaut early the next morning to begin the three-day trek back to base camp, and all hands were jubilant. For me, the plod back to base camp was accompanied by some sadness. All that remained of the old patriarch, which in its day had been a noble bull, were those grand tusks, now lashed to the saddle of one of our protesting camels. I thought too of my close-knit crew of fine fellows who’d been with me for so many years. With a few exceptions, the same crew had been with us on Bob’s first safari nearly 10 years before. Each would now seek new employment, filling a gap in some other professional hunter’s safari crew.

This was to be Bob’s last safari in East Africa, a land he loved dearly and had written about so eloquently, eventually being rewarded with fame and fortune.

As for myself, it was to be the closing of an eventful 17-year chapter in the book of my hunting career, and the beginning of a new chapter taking place in “uncharted territory” in the British protectorate, then named Bechuanaland, and now called Botswana.

For Bob Ruark and myself, the safari had been, in all respects, truly a “Kwaheri Safari!”

“Shoot Straight!” On Rifles & Stalking

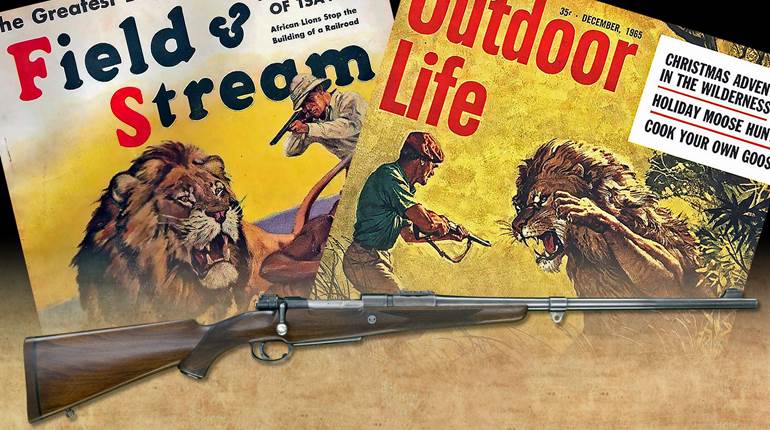

Besides my .416 Rigby and Bob’s .400/450 Jeffery (August 2009. p. 83) we decided to pack only one other center-fire rifle on our final leg of the safari. It was a Winchester .375 Holland & Holland Mag. fitted with a detachable scope, which had been given to me in 1950 as a gift from a father and son with whom I’d been on a three-month safari. We planned to use the .375 H&H Mag. for procuring camp meat, and although unnecessarily powerful for that purpose, it would also act as a substitute should either of our heavy rifles be rendered unusable. We carried 270-gr. expanding bullets for collecting camp meat, and 300-gr. solids for heavy-duty work in case the .375 was called upon in an emergency.

This particular .375 rifle had seen a lot of use since it came into my possession, as hunters in those days often brought along a .30-’06 Sprg. or some other light rifle and hired a heavy double rifle from the outfitter. I generally encouraged a hunter unless he had previous experience in handling a heavy double to use my .375 instead, as it takes a lot of practice to shoot an iron-sighted heavy double well.

Many took my advice and benefited from the increased accuracy and additional effective range the .375 H&H provided, resulting in a noticeable reduction in wounded animal follow-ups. I must emphasize that in my opinion the .375 H&H is possibly the greatest and most versatile cartridge ever invented. It has adequate power, good accuracy, and the recoil is very manageable.

Today, with such a vast range of fine premium bullets available for the .375 H&H, in the hands of a good marksman, it’s suitable for just about any big-game hunting situation. I’ve always advised visiting hunters, who will be assisted by a professional hunter with a heavy-

caliber, back-up rifle, to choose a good .375 H&H rifle fitted with a 1.5-5X riflescope with good-quality quick detachable mounts. Hunting clients generally shoot more accurately with such a rifle, more so than with a powerful, heavy-recoiling double rifle.

Last, we took along my little Browning single-shot .22, which had been a gift from my parents for my eighth birthday. It was small, but it was accurate and could be packed anywhere or easily carried by one of the men—ideal for collecting birds for the pot without making much noise. Bob unlimbered the shotgun only when we were sure there were no elephants within earshot.

It was with this little rifle that I learned to shoot, and early on my quarry was small game like pigeons, guinea fowl, spur fowl and hares. Occasionally, I hunted small predators such as jackals and wild cats when they got after the farm chickens. My world was the vast game-rich countryside surrounding our farm, and as I grew older, and when accompanied by an elderly native D’orobo farm worker, I carried the little Browning farther afield, hunting larger game such as impala, Grant’s gazelle, Thomson’s gazelle, bushbuck and duiker. My family and our farm staff never lacked for fresh venison as I hunted frequently and at every opportunity.

The D’orobo are not from any particular tribe, but live in small, scattered clans, existing entirely by hunting and gathering. Their skills in the field are unsurpassed, so with the guidance of the D’orobo who accompanied me, I learned to track and stalk game. I learned to belly crawl up to game using the most meager cover in order to get as close as possible to aim for the neck or behind the shoulder. Both points of aim offer little resistance to the limited power of the diminutive bullet.

He taught me to use my eyes and ears, as well as my nose, and to be patient in order to remain motionless for long periods of time waiting for an animal to come within range. He demonstrated the element of surprise— when it was impossible to get close—a sudden dash from concealment often placed one within range before the surprised animal reacted.

I learned to watch the interactions of different creatures, especially birds, whose behavior often indicates the presence of another bird or animal. Eventually I recognized a strange tension when we were in the proximity of game, although we were unaware of its presence. At first I couldn’t understand the significance of this feeling, but came to realize that it was a type of sixth sense. It became even stronger with experience and helped greatly in my professional hunting career when having to follow dangerous animals, wounded or otherwise, into thick bush.

As a hunter I have always thought of that old man as my mentor, but I learned an even earlier unforgettable lesson, which happened like this:

I was around 10 years old. One day our pack of farm dogs chased a large mature waterbuck bull weighing about 400 lbs. into a fairly deep pool in the river, which ran close by our home. Waterbuck often do this to defend themselves against short-legged predators, who have to swim to get to them.

My mother, two sisters and I ran down to see what the commotion was all about. The dogs barked furiously and swam around the waterbuck, which lunged at the dogs with its horns. We stood on the bank about 20 yds. away. Since I had brought the little Browning .22 my mother, who stood behind me, told me to take careful aim at the waterbuck and shoot him. But my aim was off, and I completely missed the animal. My mother gave me a smart cuff on the ear and commanded, “Shoot straight!” With the next shot, I hit the animal behind the ear and killed it instantly. That was a lesson learned, and I’ve never forgotten her words to “shoot straight!” For many years the little Browning saw less and less use, but I was happy to take it out again into real wild country. I looked forward to hearing its sharp crack again, and knowing that with the sound the larder would not be bare.

—Harry Selby