I lay prone on the red-hot Kalahari dune and waited on the blue wildebeest to clear the herd. With the rifle’s plastic fore-end wedged smartly between the rubber eyecups of my binocular, my hasty shooting position felt as stable as a sandbag. Pending luck and a well-placed bullet, the bull’s backstraps would soon be our camp’s main course.

As I waited in ambush my mind wandered. I reflected on how I’d gotten here, so far away from the deer and ducks of my home, and more specifically, how the 5-lb., budget-priced rifle—a sharp departure from Kimber’s norm—had come to be. Notwithstanding a jaunt over the Atlantic rife with pitfalls, firearm permits and near jail time in Germany—it was a winding road indeed.

The now-wholly American brand called Kimber Mfg. took a rather convoluted route to marketing the rifles for which it is now famous. You might be surprised that Kimber’s story started not in Oregon, but in a seaside “City of Churches” in the Australian Outback. It goes like this … .

Kimber’s Story

Adelaide, the capital of South Australia, is home to the majority of the giant land mass’ 1.5 million residents, and was also home to a citizen named John Llewellyn “Jack” Warne. Born in Kimba, a tiny bush town located on the Eyre Peninsula, Warne was a hunter, shooter and natural entrepreneur who started one of the biggest Australian construction companies at that time. (At one point, he was American ammunition giant CCI’s most valuable customer thanks to his company’s massive purchases of .22 blanks for its nail guns). In 1947, after World War II, the 23-year-old Warne recognized a need for sporting arms since most had been acquisitioned by the federal government for the war effort. So he founded Sporting Arms Limited—later simply called Sportco—where he began making sporting rifles for the public. You might recognize a few Sportco models such as the Model 62 in .22 Long Rifle, as its design was later sold to Winchester, which rebranded it the Model 320 and sold tens of thousands of units.

Under Warne’s leadership, Sportco was successful in firearm design and sales in markets both foreign and domestic, offering semi-automatic rifles, bolt-actions and pumps in smallbore rifles, rifles for big game and target shooting, and sporting shotguns. The company carried on for 20 years until Oregon-based Omark purchased Sportco in 1966 and hired Warne as general manager, relocating him across the world to Portland in ’68. Warne’s history with CCI led to Omark acquiring CCI, Speer, RCBS, Outers and Weaver in 1975. You’ve heard of Warne Scope Mounts? Warne started that company in 1991 after retiring from Omark in 1985. He also designed two rifle actions, a rimfire Model 82 and center-fire Model 84 in the late 1970s. At the time of this writing, Jack Warne is 92 and doing well.

With his father officially working for Omark, Greg Warne—Jack’s late son—used the two actions as a platform for the new family business, a high-end rifle company started in Clackamas, Ore. Both father and son saw a market for adult-style, sporting .22 rifles, especially since the Winchester Model 52 was defunct. After all, what hunters and shooters do not like a quality .22 rifle, accurate enough to win a competition yet practical enough for squirrels? When naming the company, Jack reflected on his joyful days hunting varmints around Kimba—the aboriginal name meaning “bush fire”—but added an “R” to give it an American ring. In 1979, Kimber of Oregon was born.

Kimber’s first rifle was similar to Sportco’s Model 44, yet when Jack invited outdoor writers of the day on a varmint hunt to test it, Outdoor Life’s Jim Carmichael rather sarcastically asked why its stock was so ugly. The rifle was functional, but a belle it was not. Heeding the scribe’s advice, what followed was an American-style .22 rifle that, in addition to a made-in-house match-grade trigger and barrel, featured an American-style, straight-comb, full-grain walnut stock designed by Darwin Hensley. The Model 82, available at one time or another in 11 models, was the company’s flagship. But the Warnes had visions of expansion.

Using the new Model 84 actions, Kimber soon specialized in making heavier-weight, small-caliber center-fires for benchrest shooting and varmint hunting. Perhaps the ultimate prairie dog gun, they were tack-driving accurate with outstanding barrels, stocks and triggers, and heavy enough to negate recoil. Quite simply, the Kimber 84s could make a novice shoot like a distinguished expert.

It was this success combined with customer demand that urged the company into producing a long action in 1989. The resulting rifle was called the 89 BGR (Big Game Rifle). Unfortunately, the company’s production demand overmatched its capability, and ultimately forced timber magnate/investor Bruce Engel—who had stepped in to rescue the company—to liquidate and sell Kimber of Oregon in 1991. Many talented employees, including Dan Cooper who would later form Cooper Arms, left. But Greg Warne had other designs.

In 1993, with the financial backing of Philadelphia businessman Les Edelman and the expertise of Boyd Metz, the trio started Kimber of America and focused the company on what it did best—high-end rimfires. Edelman bought Greg Warne out of the company and consolidated its rifle manufacturing to facilities he’d recently purchased in Yonkers, N.Y. The facility was Jericho Precision (JP), a defense contract machining company. (JP’s production manager—and later general manager of Kimber Mfg.—was Ron Cohen, presently CEO of SIG Sauer.)

With collaboration from handgunning champion Chip McCormick, Edelman retooled Kimber’s production to produce the venerable M1911 handgun. The timing was perfect, thanks to President Clinton’s gun ban in 1994 that outlawed high-capacity magazines and spurred consumer desire for an all-steel .45 ACP pistol to compete with the polymer, low-capacity 9 mm Lugers of the day. By 1997, all Oregon facilities had been moved to Yonkers, the company’s name changed to Kimber Mfg. and the pivot to handguns would almost begin to define the company—almost.

The Warnes, Edelman, Cohen and new Vice President of Marketing and Sales Dwight Van Brunt knew Kimber was still a rifle company at heart, and the operation was now better poised to innovate.

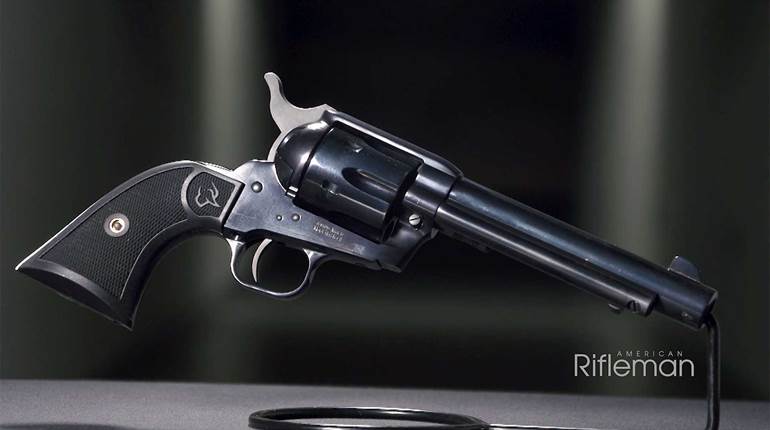

What was produced in 2001 proved to be game-changing. The Model 84M action, a proportionally sized clone of the pre-’64 Winchester Model 70, was designed by Kimber’s Nehemia Sirkis. It featured Mauser 98-style controlled-round feeding, dual locking lugs—with a third made by the root of the bolt’s handle—a forward recoil lug, three-position Model 70-style safety, blade-style ejector and an adjustable trigger. By any measure, it’s a superb action that forms the basis for all subsequent center-fire Kimber actions. Kimber already had a great brand name; now it had a new product to market.

Modernizing Kimber Rifles

Van Brunt strongly believed that there remained great demand for high-end center-fire sporting rifles, just as Jack Warne had years earlier. But he also realized technology had advanced. American hunters still wanted quality rifles, but many sought lightweight composite stocks and stainless steel barrels—guns that could be dragged up a mountain in the pouring rain. So Van Brunt went to work from Kalispell, Mont.

In late 2002, Kimber’s maiden departure from traditional walnut began. Called the Montana, the rifle featured Kimber’s proportionally optimized 84M action cradled in a hand-laid carbon-fiber stock and stainless No. 1-contour barrel. Chambered in .308 Win., the rifle weighed a feathery 5 lbs., 8 ozs., making it perfect for mountain hunting. Yet because the action was lithe, the rifle’s point of balance remained on the forward action screw even with a .308’s standard-length 22" barrel. This gave the Montana a marked advantage over lightweight production rifles that merely save weight by skeletonizing, fluting and hacking barrel length. For around $1,200, sportsmen could own a custom-like, ultra-lightweight rifle.

Sixteen years ago, $1,200 for a rifle was fairly expensive. Now, at $1,427, and with the addition of a threaded barrel for a suppressor, the Montana represents one of the better lightweight rifle bargains available. Today the company offers five featherweight rifles, including the Montana, Mountain Ascent, Adirondack, Hunter and the new-for-2017 Subalpine. But more on those later.

From there, Kimber became enthralled with the concept of building rifle actions to fit their intended uses. Much like a best-quality shotgun maker would never build a .410-bore on a 20-ga. frame, lest it result in a poorly balanced gun, Kimber believes in the same principle for its rifles. In 2003, the 8400 WSM action made its debut to take advantage of the popularity of the fat new short magnum cartridges. The action was identical in function but beefier to handle higher pressures.

With the company growing and its proportionally optimized action concept taking hold, Kimber’s next move was predictable. Certainly the company had tried and failed in 1989; but this time, Kimber Mfg. had the production capabilities to pull it off. So, in 2007, Kimber released its Model 84L.

The 84L is the same thickness as the 84M, just 0.77" longer to accommodate .30-’06 Sprg.-length cartridges. Soon Kimber released Classic, Select, Super America and Montana models chambered for America’s most popular long-action (sometimes called standard-length) hunting chamberings. As several writers of the day—including American Hunter’s editor in chief and this magazine’s own Mark Keefe—noted in reviews of the gun, the 84L action was long enough to eject spent magnum cartridges, and hinted at a true magnum rifle to come.

Indeed, there was a market deficiency in high-quality production guns for dangerous game. Hunters insisted on controlled-round feeding, but other than CZ and Winchester, there weren’t many affordable options available. An avid hunter himself, Van Brunt realized Kimber’s action would be perfect in this role, if only it were bigger.

In 2009, Kimber released the 8400 Magnum action that added to the length of the 84L and combined it with the robustness of the 8400 WSM. Models that utilized this action were the 8-lb., 10-oz., Caprivi chambered in .375 H&H Mag. and .458 Lott (.416 Rem. Mag. was added later), and later the 7-lb., 8-oz, Talkeetna in .375 H&H Mag. While the Caprivi, named for a game-rich strip of land in Namibia, targeted safari clients who often prefer traditional walnut, the Talkeetna was the Alaskan bear and moose hunter’s dream, thanks to its carbon-fiber, glass-and-pillar-bedded stock and stainless finish. Both rifles are purely Kimber, with match-quality barrels and triggers, yet both feature robust express sights, hearty recoil pads and a barrel band that relocates the sling swivel forward. All told, they’re flawlessly designed. Today you can buy the Caprivi or the Talkeetna for $3,200 and $2,100, respectively.

Kimber … Currently

Somewhere around 2010 the tactical rifle craze exploded like a flashbang, and Kimber accommodated demand by introducing four rifles that feature custom-designed heavyweight stocks and heavy-contour barrels melded to the company’s vaunted actions. Most significantly, all rifles in its tactical category are guaranteed to shoot sub-half minute-of-angle (m.o.a.) groups.

A great example of just how far Kimber has sprawled from its roots can be found when it introduced its 11-lb., 6-oz., Advanced Tactical SOC (Special Operations Capable) rifle that featured a side-folding, adjustable, aluminum chassis stock to house its 8400 Magnum action and heavy barrel. The action was fitted with a steel, five-round detachable box magazine and an oversized bolt handle. Topped with Picatinny rails and a muzzle brake, it retailed for $4,400 and shot like the counter-sniper rifle is was.

But then, as always, a shark-like industry responded. In 2015, mass-production gun companies such as Ruger and Savage introduced new waves of heavy-barreled tactical rifles that cost much less than the Kimbers. But the gun company from Kimba is currently firing back.

For 2018, Kimber has updated the Advanced Tactical SOC rifle with its SOC II. The folding-chassis-stocked rifle features a 22" threaded barrel, a forward night vision optic mount, an underside accessory rail, five- or 10-round Accuracy International-pattern polymer box magazines and the 0.50" accuracy guarantee that came with the original. Offered in .308 Win. or the popular 6.5 mm Creedmoor, Kimber reduced the original SOC’s price by about 45 percent to $2,449. For this price, I can’t readily name a premium tactical rifle available that compares in terms of quality and features. Consider that its McRees Precision G10 Standard stock—with features such as fully adjustable fit, integral bubble level and copious Picatinny rails—is very expensive on its own. Kimber offers it in sniper gray or flat dark earth models.

Noting the current push for loosening suppressor laws and a niche market that’s pushing tactical rifle makers to make them as compact as possible, Kimber also updated and reduced the cost of its SRC (Suppressor Ready Compact) rifle. With a 16" threaded barrel and aforementioned McRees folding chassis stock, this .308 Win. remains legal for non-NFA purchase, yet can be folded into an arm-sized package that fits into a backpack with the barrel only poking out slightly. With the hinged aluminum stock fully extended and a silencer screwed onto the muzzle, the rifle is right at the typical length of a normal tactical rifle, but one that is suppressed. Of course, velocity of the .308 Win. round suffers slightly due to the stubby barrel, but I can think of many mobile SWAT teams, plain-clothes operators and even long-range endurance-style competitors for whom the SRC II will shine. Like the SOC II, it’s also shipped with a denier nylon drag bag. Amazingly, it now costs $2,449 as well.

On the more traditional tactical spectrum is the LPT (Light Police Tactical) that could perform double duty as a hybrid target/hunting rifle thanks to its sub-half-m.o.a. guarantee, 22" fluted bull barrel, Picatinny rail, laminated-and-epoxied wood stock, matte finish, 8-lb. weight and modest price tag of $1,400. I can think of no other rifle guaranteed to shoot 0.50" groups in this price class.

These updated tactical offerings along with their new price points indicate that Kimber is doing its best to remain nimble and competitive in an unpredictable market that swings wildly with consumer trends.

Of course Kimber still churns out its bread-and-butter varmint rifles—it currently offers six heavy-barreled, wood-stocked models in small-caliber center-fires—but most notable is its latest 2017 model called the Open Country.

A coyote or long-range deer hunter’s delight, it features a reinforced carbon-fiber stock that’s then given a rubbery soft-touch treatment before it’s dipped in Gore’s Optifade camouflage. Its 84M action is chambered in the outstanding 6.5 mm Creedmoor cartridge. Combined with a 24" fluted barrel, the rifle checks in under 7 lbs., lending it a great mix of accuracy and mobility for $2,200 retail.

For all of Kimber’s rifle categories, however, perhaps the most impressive—from an engineering standpoint—is its lineup of ultra-lightweight rifles that spawned from the Montana. These models are available in three different action lengths, made evident in their respective weights. It underscores the importance of Kimber’s investment in its proportionally sized action concept. Today, Kimber offers the Montana, Mountain Ascent, Adirondack and its new Subalpine. These rifles are made in Kimber’s new state-of-the-art facility in Ridgefield, N.J.

Coated in a soft touch, Gore Optifade “Subalpine” pattern, the Subalpine rifle weighs an unbelievable 4 lbs., 2 ozs., in .308 Win. (84M action) with a threaded, bedded, partially fluted barrel; 5 lbs., 8 ozs., in a 24" barrel .280 Ackley Improved or .30-’06 Sprg.; and 6 lbs., 8 ozs., in .300 Win. Mag. Most impressive is that it, like the others, is guaranteed to deliver sub-m.o.a accuracy.

The Adirondack, with its threaded 20" tube, weighs just 4 lbs., 2 ozs., and, chambered in 7 mm-08 Rem. and .300 Blackout among others, is perhaps the ultimate truck and tree stand rifle. They represent the pinnacle of ultra-lightweight rifle technology. And because they are factory rifles, they cost around $1,700, a bargain considering the craftsmanship and materials within.

By 2015, if you thumbed through Kimber’s catalog (photographed, as always, by Mustafa Bilal), you might notice that most all bolt-action rifle niches were covered—except one. The low/mid-priced category. No doubt there were fiery internal debates about whether lowering the cost of a rifle by half would also lower its quality and, therefore, the brand’s reputation, but when it was all said and done, executives felt it could have its market share and keep its Kimber too.

And that brings us full circle, to Kimber’s farthest departure from its rich history to date, and the one I had cradled between my cheek, shoulder and the conforming Kalahari sand. Kimber’s new 5-lb., 8-oz., Hunter model, thankfully, uses the vaunted 84M action, trigger and barrel, but it’s planted in a polymer—a fancy name for plastic—stock. Injection molded by a third-party vendor for Kimber to the same exterior dimensions of its other lightweight stocks, it utilizes two aluminum pillars that also serve as action screw spacers, a molded recoil lug recess and a honeycomb structure that adds some rigidity. The integrally molded trigger guard does away with bottom metal altogether, saving cost. The flush-fitting, detachable magazine is a combination of plastic and metal. Its plastic latch, which mandates the magazine be placed in the rear of the well and rocked forward, leaves something to be desired. I must report that I experienced a couple of jams that occurred when the magazine was both full and when rounds slid forward in the magazine after the rifle was jostled, causing the tip of the second round to impede feeding. Still, plastic-stock-feel and feeding hiccups aside, the Hunter is a lot of ultralight rifle for $700, even before its sub-m.o.a. accuracy guarantee. (See Craig Boddington’s article, “Meet Kimber’s ‘Hunter,’” Jan. 2017, for a full review. In it, he mentioned no feeding issues, so perhaps my test unit was an anomaly.) Editors of this publication’s sister magazine, American Hunter, liked the Hunter so much they awarded it with a Golden Bullseye Award for 2017 Rifle of the Year.

My Hunter averaged three-shot groups of 1.35", but produced a few under an inch with Federal’s Copper 150-gr. ammunition. Five-shot groups averaged 1.6". (See sidebar, “The Ultra-Light Tradeoff,” p. 53). But all I needed from it now was one good shot, from 305 yds., according to my Nikon rangefinder.

Moments later the young bull unexpectedly stopped and turned broadside.

Blam! The rifle lurched. Whop! The bullet reported. The beast, one of the most iconic of Africa’s plains game, kicked as if heart shot, then sprinted 20 yds. before confirming it. I stood just as a mighty slap on the back from Dreis, my professional hunter, rocked me forward in unspoken approval. I racked the Kimber’s bolt and slung it over my shoulder so lightly that it would almost be forgotten until I’d depend on it again.

As the storied rifle company with the distinctive name enters 2018, there’s at least one model that’s made from the action up specifically for your intended use. And if you always wanted one but previously couldn’t afford it, now there’s a Kimber for you, too.

For more information, contact: Kimber Mfg., Inc. (Dept. AR), 555 Taxter Road, Elmsford, NY 10523; (888) 243-4522; kimberamerica.com.

The Ultralight Tradeoff

The only two complaints I’ve ever heard about Kimber both concern its ultra-lightweight rifles. The first complaint that is that the rifle is “whippy.” Frankly, a 5-lb. rifle with a No. 1-contour barrel is whippy. It’s like buying a ‘69 Camaro and complaining that it fishtails when you mash the gas. But, thanks to Kimber’s lithe 84M action that’s lighter than nearly all other production guns, the company’s mountain rifles are built to balance better than comparable rifles while not sacrificing barrel length. They may not be weight-forward like your 8-lb. Mauser, but they were never intended as such.

Secondly, plenty of shooters—including this one—have experienced lightweight rifles that throw fliers after five shots or so. I’ve shot Kimbers with this tendency. It drives perfectionists crazy, and certainly looks bad in magazine articles because it causes the rifle’s average group size to swell. This tendency, however, is the downside of pencil-thin barrels that heat rapidly, and thus, change position.

Kimber’s ultralights are intended as hunting guns, not benchrest rigs. They’re specifically made to be easily carried, because after all, rifles are carried for 99 percent of a hunt. And when they are fired, they’re fired with a cold bore. What is important is that it prints to point of aim, on the first shot, every time. You should also know that ultralight rifles are more finicky about ammunition. I recommend trying at least five loads, and preferably more, to find the most accurate.