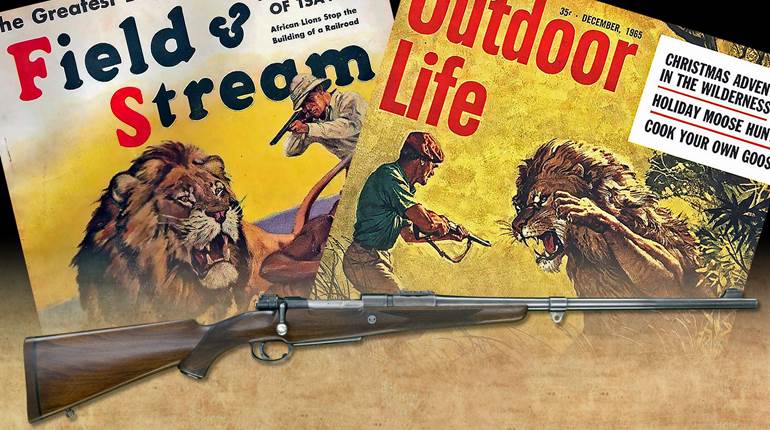

Horn of the Hunter by Robert Ruark is regarded as one of the greatest hunting books ever written. And it would not have happened without the owner of this very special Colt Woodsman, Harry Selby, who carried the pistol daily on nearly a half-century of safaris.

Although largely recognized as a big-game hunter with a penchant for big-bore rifles, Ernest Hemingway also held certain small-bore chamberings in high esteem. In particular, he favored the .22 Long Rifle, for which he once claimed boldly, “… standing in one corner of a boxing ring with a .22 caliber Colt automatic pistol, shooting a bullet weighing only 40 grains and with a striking energy of 51 foot pounds at 25 feet from the muzzle, I will guarantee to kill either Gene Tunney or Joe Louis before they get to me from the opposite corner.” It was certainly strange indeed that the old master used this macabre scenario to illustrate his implicit faith in the .22 caliber, but he obviously wanted to emphasize his point.

Hemingway followed with this admonition, “The rifle and the pistol are still the equalizer when one man is more of a man than another, and if … he is really smart … he will get a permit to carry one and then drop around to Abercrombie & Fitch (New York gun shop) and buy himself a .22 caliber Colt automatic pistol, Woodsman model, with a five-inch barrel and a box of shells. This is the smallest caliber pistol cartridge made; but it is also one of the most accurate and easy to hit with, since the pistol has no recoil.”

Ironically, and in direct contradiction to Hemingway’s claims about the .22 caliber’s capabilities, just recently a Florida man accidentally wounded himself while cleaning his .22 handgun—it was three days later before he discovered blood on his shirt and realized he’d previously shot himself. The incident raised many questions, and eyebrows, to be sure, but the police investigating the mishap determined it was an accident and did not file charges. As the old saying goes, “You’ve gotta be tough, if you’re gonna be stupid.”

Clearly, Hemingway’s opinion of the .22 Long Rifle was pushing the envelope of reality, but what he did get right was his recommendation to buy a Colt Woodsman. He owned at least three Woodsmans, the first of which was a First Series Target model with a 6 5⁄8" barrel made in 1919, which can be seen in a 1920 photo of Hemingway wearing it in a shoulder rig while fishing in Michigan. He later purchased a pair of Second Series Match Target Woodsmans with 6" slab-sided barrels and checkered walnut grips from Abercrombie & Fitch in June 1953. He was on his way to East Africa on his second safari and, undoubtedly, one or both of the Woodsmans were part of his safari battery.

Hemingway’s second safari took place during the peak of the Mau Mau Uprising in Kenya. In spite of suggestions that he carry his Woodsman on safari for purposes of self-defense, Hemingway used his little Colt mostly against camp pests, such as jackals and even scorpions crawling out of the firewood.

Hemingway never mentions having a pistol in The Green Hills of Africa, but alludes to a .22-cal. pistol in Big Two-Hearted River, one of his most popular stories. While Hemingway never dropped big game with his Woodsman, he still favored it as an all-purpose sidearm, and it stands as a unique and often-overlooked part of the Nobel laureate’s gun collection. Interestingly, one of Hemingway’s Second Series Match Target Woodsmans, along with a leather holster and corroborating paperwork, sold at auction in October 2007, fetching just under $11,000. A Woodsman’s value only goes up with time, and I would guess that today Hemingway’s Colt would bring substantially more than that.

Though handy with .22-cal. pistols and revolvers from my early plinking days, it wasn’t until the mid-70s that I became familiar with the Woodsman. That happened to be a few years before the Woodsman’s 62-year production run ended. At the time, I worked for Ker, Downey & Selby (KDS) Safaris in Botswana, and my boss, none other than Harry Selby, happened to own the Woodsman. Selby is a true gun aficionado, having grown up on a farm in Kenya where he collected birds and small game for the family’s larder from the age of 8 with a .22 Long Rifle-chambered bolt-action. His love and respect for the .22 caliber began early and has lasted throughout his life—he still owns that original .22 rifle with which he shot his first game.

He came by the Colt Woodsman in 1962, when clients left it with him at the end of their Kenya safari. During its “baptism-by-safari,” the Colt pistol was used for general plinking fun and for collecting small game such as dik-dik and guinea fowl for the pot. Selby was impressed with the Colt’s performance and, by the end of the safari, he had gained much respect for the little semi-automatic, so the family was pleased to present the Woodsman to Selby as a gift upon their departure.

When Selby moved to Botswana the following year, he shipped all of his firearms to his new home in Maun, which included the diminutive Woodsman pistol among an impressive array of both big- and small-bore rifles and shotguns. During the next 40 years of conducting safaris in Botswana, among the many firearms he owned, the two guns that Selby never left home without were his .416 Rigby and the Colt Woodsman.

On one occasion, when he needed to resolve a problem in camp, Selby remembers thinking his Woodsman was the gun for the job. Selby and his client were hunting out of Splash Camp, located beside a flow of water near a small lagoon on the edge of the Okavango Delta. During dinner one evening, Moffet, the waiter, came to tell Selby that Shu Shu, the skinner, wanted to talk to him. Selby found this request quite amusing as Shu Shu was both deaf and dumb. Although Shu Shu could neither hear nor speak, he communicated effectively in other unique and demonstrative ways, but Selby insisted that Moffet tell him what was going on. It transpired that Shu Shu had seen signs of a kwena (crocodile) lurking in close proximity to the camp’s skinning area. Extremely protective of the skins and horns in his charge, Shu Shu had set a trap that snagged the croc. Now it needed to be dispatched.

Selby, assuming the perpetrator would be your common seven- or eight-footer, sent Moffet to his tent to fetch the Woodsman, figuring a brain shot from the .22 was just the ticket to eliminate the nuisance and end the croc’s troubles. Selby and his client, followed by an entourage of camp staff, marched over to the skinning area where Shu Shu waited. Shu Shu then led the group around to the back of the skinning area and pointed to a stretch of wire extending into some grass at the water’s edge. The first thing Selby noticed when he shone his flashlight on the 8-gauge wire was that it was extremely taut. When his eyes followed the light beam down the wire and focused on what lay there, Selby got the fright of his life. There, straining at the end of the wire, lay an absolute monster crocodile. The wire seemed ready to snap, having been pulled and tugged against by all of the sizeable brute’s tremendous strength and force. There is no doubt this croc could easily have been a man-eater, with the girth of his stomach as big around as a buffalo’s.

“Good Lord! This is no .22 croc!” Selby exclaimed to his client, and then turned to Moffet to ask him to run to get his .416 Rigby. He hoped the wire would hold long enough for Moffet to return with his rifle. It did, and with a single .416 shot to the brain, Shu Shu’s croc concerns were over. Selby remembers the Woodsman feeling ridiculously small in his hand when he first glimpsed the monster croc—he felt much better taking ahold of his .416 Rigby.

Another useful duty for Selby’s Woodsman was to administer the coup de grace when an animal was down, but not yet dead. You could tell which of Selby’s clients were good shots by looking at the backs of the skulls in the skinning shed. When many of the skulls collected by any particular client displayed a discreet little .22-cal. hole behind the horns, you could draw your own conclusions.

Selby and I conducted a number of memorable safaris together, and if ever we met up for lunch in the field with our clients, it usually meant a friendly little shooting competition with the Woodsman, dispatching any overly ripe fruit from the lunch box in a spray of juice and pulp. Those shooting sessions kick-started my own interest in owning a Woodsman and, during the next off-season, I located and bought my own—a cherry, new-in-box Third Series Sport Model Woodsman that had never been fired. Like eating potato chips, one is never enough, and over the next couple of dozen years, I kept a sharp eye out for any Woodsmans in good condition that I could find at a fair price, and eventually accumulated a modest collection of representative target and sport model Woodsmans from all three series.

The Colt Woodsman sprang from a design by John Moses Browning in 1915. During the first two decades of the century, Browning designed the larger Colt Models 1900 and 1902, as well as the Models 1903 and 1908 Pocket Hammerless and the Vest Pocket pistol. Too, he designed the most famous of Colt handguns, the Government Model or M1911. These guns ranged in caliber from .25 ACP to .45 ACP, and were all made for the purposes of self-defense or military and law enforcement use. What the company needed to complete its handgun offerings was a good rimfire target pistol. And that is just what Browning came up with.

The new .22 semi-automatic pistol was an exercise in simplicity. Browning started with a fixed barrel attached to a straight-blowback action, meaning that the barrel was threaded solidly to the forged-steel frame. This ensured that as long as it was aligned properly in production, it couldn’t be knocked loose later. The back of the frame included a removable slide that held the mainspring housing, striker-style firing pin and a spring-loaded extractor.

The pistol was fed from a single-stack, 10-shot-capacity magazine that was inserted into the pistol grip and held there by a European-style heel release. While it was unlike Browning to do this, considering that he had already designed several semi-automatic pistols with push-button magazine releases, including Colt’s M1911, it did make the gun bilateral and easy to load or unload while wearing gloves. The trigger guard was also large enough to accommodate a gloved finger if needed. Since the gun was promoted as a sidearm for farmers, ranchers and woodsmen, these were welcomed features.

A drift-adjustable rear sight and elevation-adjustable front sight was inlet directly into the gun. With a long sight radius over the 65⁄8" thin barrel, these sights helped make the gun exceptionally accurate. A thin trigger with very short travel reduced the possibility of an inexperienced shooter jerking it, which also helped with accuracy. Checkered walnut stocks covered an angled grip frame similar to the one found on Luger’s Parabellum pistol—popular among both military and target shooters at the time. Overall length was 10½" and total weight with a loaded magazine was less than 2 lbs. Browning presented his gun to Colt, which received it enthusiastically and sold it as the simply titled “Colt .22 Automatic Pistol” starting in 1915.

Over the course of its production history, three series of the Colt Woodsman evolved, with each offering three different models—Target, Sport and Match Target, which corresponded to three basic frame designs. Originally, the Sport Model had a 4½" round barrel, the Target Model had a 6 5⁄8" round barrel and the Match Target Model featured a heavy, flat-sided 65⁄8" barrel. In the post-war versions the barrel lengths were either 4½" or 6".

First Series (1915–1947) refers to all the pistols built on the S-frame as it existed prior to and during World War II. The Target Model was the base model of the Woodsman and featured a 6 5⁄8" barrel with a step-down shoulder at the rear of the straight, no-taper “pencil barrel.” The sights were adjustable, both front and rear. In 1927, the “Woodsman” name was added to the model with the pistols made prior to that referred to as “pre-Woodsmans.” The Sport Model was introduced in 1933, featuring a 4½" barrel and designed as a field sidearm for hiking and camping activities. The Match Target Model made its debut in 1938 and featured a heavier barrel with a one-piece wrap-around grip known as the “elephant ear.” A “Bullseye” icon was roll-marked into the slide, and the gun was nicknamed the “Bullseye Match Target.”

In 1941, as the United States entered World War II, Colt ceased civilian production of the Woodsman, having sold an estimated 690,000 of the pistols in three different variants by then. But, as late as 1945, delivering 4,000 Match Target models to the U.S. government marked with a government cartouche and U.S. markings, they served for decades before they were passed along to the surplus market.

Second Series (1947–1955) Woodsmans include all versions built on the second S-frame design. Colt resumed production of the Woodsman in 1947 with three models remaining similar, but built on a longer, heavier frame and incorporating a magazine safety, automatic slide-stop and push-button magazine release located at the rear of the trigger guard. Special versions were made for the U.S. Marine Corps (100 Match Target Models and 2,500 Sport Models); U.S. Air Force (925 Target Models); and U.S. Coast Guard (75 Match Target Models). The Air Force models had no special markings, and most were sold as surplus through the Director of Civilian Marksmanship Program. The bulk of the Marine and Coast Guard versions were destroyed and sold as scrap metal.

Third Series (1955–1977) refers to the Woodsman’s third S-frame design change. The three models again remained similar, but the markings, grips and sights underwent slight changes. The most significant change was relocating the magazine release from the rear of the trigger guard back to the heel of the grip as on the First Series. In 1960, walnut stocks with a thumb rest became optional, in place of the standard black plastic stocks. Three very similar economy models were produced during this time, which included the Challenger, the Huntsman and the Targetsman models, equipped with fixed sights.

During its six-decade production, Colt’s Woodsman set the bar high with many brands following its lead. Had the Woodsman never been designed, one can only imagine what the rimfire pistol market would look like today. The value of a “typical” shooting-grade Colt Woodsman continues to climb with each year, and owing to the nature of their construction, these guns continue to shoot remarkably well.

Last year, I had a chance to visit Selby at his home in Maun and wish him well on the celebration of his 90th birthday. We chatted and reminisced about the safaris we did together during Botswana’s “good old days,” and, of course, the croc escapade with Selby’s Woodsman was retold and fondly remembered. All of us had a good laugh about the “not-a-.22 croc” of Splash Camp. Then Selby fetched the little .22 pistol, unzipped it from the pistol rug that contained it, and handed it to me. It was a treat to once again hold and admire the venerable Colt. As I studied each character mark and scuff on the Third Series Sport model with walnut grips in my hand, Selby asked if I would like to have the Woodsman.

“You’ve always admired my Woodsman, and I know how much you like the pistol. I know it will be in good company with your other Woodsmans,” Selby said. “These days it’s spending too much time in a gun safe, and I know you’ll provide the kind of exercise it needs and enjoys.”

It took a minute for me to register the enormity of what Selby was suggesting. Yes, Selby’s Woodsman would be in very fine company, but the other guns would pale in the shadow of this very special Woodsman that had spent so many years in the African bush, carried on countless safaris in the hands of Harry Selby, one of Africa’s most well-known and most respected professional hunters.

“I would be honored, Harry, to have your Woodsman. Thank you more than I can say!” was all I could muster at the moment—it did not seem nearly adequate. Even now, to say that it’s an honor and a privilege to possess such a gun does not begin to describe the pride that I feel when I hold Selby’s revered and safari-proven Colt Woodsman.