The trend in semi-automatic pistols today is abundantly clear. Shooters want—and manufacturers are giving them—compact, striker-fired 9 mm Luger pistols built on polymer receivers and, most often, fed from double-column magazines. An old-fashioned, full-size, hammer-fired service pistol with a metal frame and fed from a single-column magazine would seem to be a thing of the past. Of course, the M1911 stands out in that genre and not only survives but thrives, with seemingly countless companies making it. But the M1911 is not the only full-size service pistol with old-school features and a light, crisp, single-action trigger pull.

This story is about another, much less widely distributed, example—the SIG P210—and in it we’ll look not only at the history of this European-made classic, which is almost universally admired by pistol connoisseurs, we’ll also examine the newest version of it—a target model made right here in America. If you do not own an original SIG P210, you are not alone, as it was never imported into the United States in great numbers. Much of the reason for that was likely the gun’s high cost. In 1997, it sold for $2,300, which is approximately $3,521 in today’s dollars—slightly more than double the new gun’s price. Also, it was produced by what was then a relatively small manufacturer, Schweizerische Industrie Gesellschaft, better known simply as SIG, with limited production capacity. Both of those earlier impediments to the gun’s success are now being remedied by the U.S.-based corporate offspring, SIG Sauer, Inc., which has installed a production line for the P210 in New Hampshire and should be able to efficiently satisfy the U.S. market with what appears to be a respectable homage to the original. In fact, given the somewhat anomalous nature of the P210 in today’s market, the American-made version should be even more appealing, as it includes several significant ergonomic improvements, finishes and updates. Before we delve into the specifics of the new P210, we need to take a look at its lineage.

A Little Background

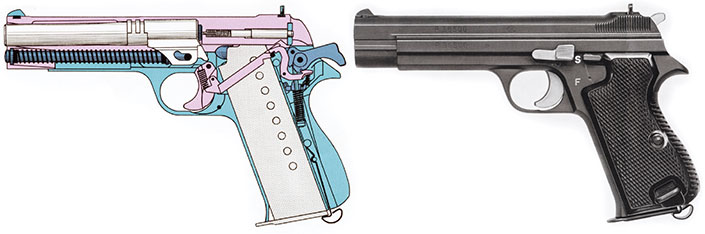

The original P210 was developed and produced to be the service pistol of Switzerland, and served as such from 1948 until 1975. The guns were also made for commercial sale in that country, which has a long history of civil defense bolstered by civilian marksmanship competition. As might be expected of a Swiss-produced arm, the original P210 displayed a high level of fit, finish and precision. It was the brainchild of Swiss-born, German-educated, gun designer Charles Petter, whose credentials were of the highest order, including design experience at the renowned Krupp works, the 400-year-old German steel concern. In the Great War, Petter was an officer of the French Foreign Legion and was the recipient of both the Legion d’honneur and the Croix de guerre for bravery under fire. He became a French citizen and worked as a designer in the French arms industry, developing the French service pistol of 1935. This graceful middleweight is a real sleeper among handguns, and, given proper chambering (something other than 7.65 mm French Long) and better controls, it could have gone on to the kind of worldwide success enjoyed by the gun over which it was chosen—but that the rest of the world considered to be superior—John Browning’s High Power. Two of Petter’s design features from the 1935A pistol carried over to the Swiss service pistol trials that started in the 1930s—reversed slide rails and plate-mounted modular lockwork.

Switzerland was a neutral nation during World War II, but maintained an active army with a very large reserve component. At that point, its service pistol was a version of the Luger, but a 9 mm pistol which came to be called the 47/8, designated Pistole 49, and, finally, P210 was developed using some of the Petter’s patents first seen on the French 1935A. Even though work had begun in the 1930s, it wasn’t until the late 1940s that the military gun was fully developed and produced in sufficient quantity to allow some commercial sale. A double-column-magazine version of the gun exists but was never made in quantity. Some decades later, in the active Swiss service, the P210 was replaced in 1975 by the much lighter, aluminum-frame, double-stack SIG Sauer P220.

Making A Classic, Here

The new SIG Sauer offering is a stylistically faithful rendition of the 70-year-old design. The original P210’s form persists because it was fundamentally a superb pistol, and the new gun’s updates are almost exclusively aimed at simplifying manufacture and improving handling and convenience. The designation of its initial model offering, Target, refers to the shapely, oversize stocks and fully adjustable rear sight. Unlike the original, which, during its 70-year production life was made in the Swiss plant at Neuhausen and in the German plant at Eckenforde—both relatively small-volume facilities that relied heavily on hand craftsmanship—today’s P210 is being made in SIG Sauer’s large, state-of-the-art factory in New Hampshire, which is full of advanced CNC machining centers. It should come as no surprise, then, that the previous model’s fine high-polish blue finish has not been retained. Fortunately for modern users, however, the new gun sports SIG’s durable Nitron treatment on its stainless steel frame and slide, which is not only attractive but quite a bit more practical as well.

The new model retains its predecessor’s major traits; it is an all-steel, recoil-operated, single-action 9 mm Luger-chambered pistol fed from a single-column magazine and featuring a manual safety. A full-size gun, the American P210 weighs 36.9 ozs. and measures 8.4" in length, 5.25" in height and 1.37" in width. That makes it bigger and heavier than virtually all current service pistols, which, again, shouldn’t come as a surprise in this particular case as it is being billed as a target pistol. The P210 will eventually be offered in three other versions, including an even longer 6" Target version and an interesting 4" Carry model.

My test sample of the 5" Target model shot exceptionally well, but before I get to that, let’s look at the updates worked into the American version of the P210. They start with the currently popular fiber-optic front sight, which is matched with a windage- and elevation-adjustable rear unit dovetailed into a boss on the top rear of the slide. The tip of the hammer on the first P210s often bit the web of the shooter’s hand, so the new version has an extended beavertail. Controls are improved by way of a more ergonomic slide lock and thumb safety, as well as a magazine catch located aft of the trigger guard—rather than on the heel of the butt in past European fashion. We also see a magazine well formed by the contour of the checkered walnut stocks and precise checkering on the pistol’s frontstrap. SIG Sauer’s designers chose to put front cocking serrations on the slide flats as well.

Engineers also modernized the way the pistol locks into battery. Instead of lugs on the top of the barrel ahead of the chamber mating with corresponding recesses in the slide’s underside, a block at the breech end of the barrel mates with the ejection port—an idea pioneered by SIG and now seen on most modern semi-automatic designs.

All of these changes were performed on a pistol that was excellent to start. It was that good because of superior execution of a superior design. A service pistol should get the shooter’s hand as close as possible to the barrel and the line of recoil thrust. That feature has been on every P210 ever made. A semi-automatic pistol has to cycle its slide in order to reload its own chamber, and that means it has to briefly break up the locked relationship between the barrel, slide and receiver. When the slide goes forward and locks, the slide/barrel/frame relationship has to be exactly the same as it was for the former shot and (hopefully) all future ones. Along with a premium barrel, this consistency is what results in repeatable accuracy. You may be certain that the P210 barrel is first-rate, so how did they make the rest happen?

Riding The Rails

They did it with a system of reversed rails. By rails, I mean the parallel rails that run along the top right and left inside edges of the receiver and mate with matching recesses in the outside of the slide. In the process of firing a shot, the slide recoils back along the receiver rails and then forward again under pressure of a recoil spring. As viewed from behind the gun, nearly all semi-automatic pistols have rails on the receiver that extend upward and then outward, so that the matching slide rails come downward and inward. In effect, this means the slide rides on the receiver. On the SIG Sauer P210, the receiver rails come upward and inward to interface with slide rails that do the opposite—extend downward and outward. In this arrangement, the slide rides inside the receiver. If you combine that geometry with extra-long rails—and precision manufacturing tolerances—you have an exceptional tool. That P210 top end does not yaw, pitch or roll, nor does it chatter, rattle or squeak; it just runs smoothly straight forward and straight rearward.

Lest anyone misunderstand, there is nothing wrong or undesirable with the conventional format. It works well on the vast majority of modern pistols. Reversed rails just offer a better degree of mechanical control. Used on only a few other guns, such as the fine Czech-designed CZ 75 and Italy’s EAA Witness (a CZ 75 clone), reversed rails are admittedly more expensive to produce.

The designers must have known they were producing an accurate pistol, but they also knew that shooters would never get the accuracy from the gun if it did not have a fine trigger. Using the same system as Petter’s Model 35A, they put the lockwork on a plate that contains the hammer, sear, mainspring and disconnector. The trigger is a simple lever that stays in the receiver. The lockwork lifts straight up and out of the receiver after the slide is removed. In doing so, parts are retained in proper relationship as they were installed after being carefully machined and fitted. It is an ingenuous concept, easing maintenance considerably.

Updating A Classic

At this point, before we get to the results of my range session, I need to mention the P210s ergonomics and handling features. The pistol’s stock panels are a good place to start. They are made from a medium shade of walnut with a great deal of figure and several panels of functional checkering. They are shaped for the work at hand, precision bullseye shooting, and have a strong so-called “coke bottle” profile. Also, the stocks flare outward at the base in order to assist the shooter in keeping the muzzle elevated. There is no thumb rest, as that would render the pistol non-ambidextrous. The grip shape is well-designed and hand-filling, if a bit large. Controls are a more modern contouring of the same system as the beloved M1911 pistol—the thumb safety and slide lock on the left upper edge of the receiver. The magazine catch is a button aft of the trigger guard on the left side. And that brings us to the trigger. It is a pivoting design housed within a rather small trigger guard. Although unusual, the trigger is one of the easiest to use I have ever experienced. Virtually all pistol triggers have a small amount of precautionary take-up before the actual release takes place. The shooter builds pressure until there is a clean break, followed by varying degrees of overtravel. My sample P210 exhibited a modicum of takeup, which was followed by trigger engagement. It released after about 3 lbs., 8 ozs. of pressure was applied, which did require slight movement, but there was no perceptible overtravel. The trigger’s action is glass-smooth and in no way distracting. It just sort of gently “rolls off,” and I liked it very much.

Remarkable Range Work

At the range, I did some informal shooting, and I found that functioning was perfect. It’s a big pistol with considerable weight, and even the hotter 9 mm loads fired did not cause anything close to distracting recoil. A smooth, easy to manage handful of gun, this new P210 benefits from large, clear sights. I got my first indication that the gun would be accurate when I was rolling one of those orange polymer targets farther and farther down range. Then I fastened the gun to my Ransom Rest, which was bolted to a concrete bench, and broke out the ammunition. The protocol used by this magazine for decades mandates five consecutive, five-shot groups at 25 yds., plus chronographing and function testing.

Usually, I use three different brands of readily available ammunition, but this shoot got so interesting that I used five. The results are tabulated nearby. The best groups were as small as 0.49", and every one of the five different kinds of ammunition had at least one group close to the half-inch mark. SIG Sauer’s own Match V-Crown was the best, averaging 0.75". In 10 shots across the chronograph screens, that match load averaged 931 f.p.s. with a standard deviation of just 5. Clearly, the ammunition is top-notch. But the average group for the whole exercise was 0.91"; that is simply superb performance. In fact, it makes the SIG P210 the most accurate center-fire pistol I have fired in the past 20 years.

Given its fine European heritage, modern-day build quality, refined features and stellar accuracy, the new American-made SIG P210 is not only a fitting homage to a vaunted classic, it is a new standard in domestically produced, heritage-grade semi-automatic handguns. For those who always wanted to own an example of the enduring P210 design, but simply couldn’t afford one, the new American-made version from SIG Sauer is certain to sufficiently scratch that itch and, after an initial range session, to reward the shooter with an enduring sense of pride.