It’s interesting how perceptions change over time. In 1955, for example, it was acceptable—normal, even—for little boys to pretend to blast each other with toy guns at recess.

Little boys haven’t changed, but perceptions sure have. Elvis used to seem risque; now that notion is laughable. In 1985, a Glock looked liked a ray gun from a Buck Rogers episode—today it’s as normal as sunshine, despite that polymer handgun looking no different than it did back then. The point is, human perception evolves with familiarity, and often it happens without our even realizing it.

Back in 2008, this magazine’s editor in chief, Mark Keefe, reviewed the then-new Browning X-Bolt rifle. He titled his story, “A Radical In The Family.” This wasn’t shortsightedness, for if anyone knows that guns and gun-buying trends evolve, it’s Keefe. (Several other gun writers penned similar descriptions, including this one who wrote of the X-Bolt’s “new-aged, race car-esque lines”.)

At any rate, as I handle the rifle today—10 years later—my own prior description of it seems strange; its design hasn’t changed from 2008, but I no longer perceive Browning’s modern flagship as radical. Until, that is, I look at it alongside an A-Bolt for context. I’m then reminded that its tapered fore-end, rounded belly and sharp shadow lines were a stark departure from its predecessor. No doubt Browning marketers named their updated rifle the X-Bolt at least in part to appeal to future generations, but time has revealed that the rifle is more than a new name and a facelift. What follows is the story of the X.

A Little Background

For a very brief history of the Browning company, without spending volumes on John M. Browning’s myriad inventions and business dealings, allow the following: The Browning company of Morgan, Utah, was contrived in 1878 to produce, market and sell non-military shooting, hunting and fishing products made by the John Browning company. Over the years it has been bought, sold and licensed numerous times. Its firearms have been made and licensed to sell by Colt, Remington, Winchester, Fabrique Nationale of Belgium and Miroku of Japan. In 1977 FN Herstal—the company that also owned U.S. Repeating Arms Co.—bought Browning Arms Co., but, despite being a gun manufacturer itself, the Belgian firm chose to keep production of many of its Browning rifles at the contracted, 124-year-old Miroku factory in Japan. Despite being Belgian-owned and Japanese-made, Browning Arms’ engineering, R&D and marketing operations are run by Americans out of its U.S. offices, and that likely explains at least one reason why Browning firearms are generally so appealing to American hunters. Another is that it was not Browning’s first crack at making American hunters and shooters happy; the A-Bolt provided valuable insight.

“A” Worthy Predecessor

Browning’s A-Bolt rifles hit dealer racks in 1984. The rifle was to replace Browning’s BBR, a bolt-action that was actually ahead of its time with its detachable magazine and absence of factory iron sights. In this writer’s opinion, however, the BBR looked too much like Remington’s Model 700 and was not distinguishable enough on its own. Sales lagged. So Browning set out to design the A-Bolt that was to feature real improvements over other rifles, such as a shorter, 60-degree bolt throw—making reloading quicker while decreasing the bolt knob’s potential to interfere with the eyepiece of a scope mounted above it—and a lighter, livelier feel.

The A-Bolt was designed to be its own rifle, what with its trim physique and lithe action. Indeed, the Micro Medallion hovered around 6 lbs. at a time when few companies were going light. It handled like a wand, and, more importantly, it shot well.

The initial A-Bolts were often dressed with high-gloss stocks, deep bluing, golden triggers and many had factory engraving. Yet Browning tracked with each trend that came along, and when the stainless/synthetic wave hit, Browning rode it with its A-Bolt Stalker and Composite Stalker models, among many others. Since 1984, Browning has introduced dozens of A-Bolt versions, and I don’t know an A-Bolt owner who doesn’t appreciate his or hers for its quality. Even so, Browning didn’t become one of the world’s most prolific producers of firearms without reason; it has never rested on its laurels or claimed perfection. Rather, it keeps pushing the envelope and selling new guns. Even while the A-Bolt was still relatively young, Browning’s American-based leadership, including now-retired Denny Wilcox (product manager), Travis Hall (vice president of sales and marketing) and Aaron Cummins (then-marketing analyst) began looking to the future.

“In about 1997 our marketing department identified a need for a new rifle. The A-Bolt was doing well, but they wanted a new generation of rifles, or perhaps rifles for a new generation,” said Marcus Heath, currently Browning’s quality manager.

At the time, engineer Joseph Rousseau was placed in charge of the project. Born in Belgium and schooled in engineering and sociology, he’d worked in Europe as an industrial design engineer before immigrating to America in 1989 to work for FN’s Browning and USRAC (Winchester) brands, namely on its shotguns. Today, he’s Browning’s director of research and development, in charge of all guns that Browning designs. He’s also passionate about motorcycles and automobile design. In the late 1990s he was tasked with designing the X-Bolt concept from the ground up.

“I assembled the team, and gave them the guidelines,” said Rousseau. “In short, Browning wanted a superior rifle.”

“[Marketing] called for a totally new, accurate rifle with new features and updated styling,” Heath said. “We wanted a detachable magazine, increased rigidity of the action for accuracy, an improved trigger and a three-position safety. And all of this would have been fairly easy,” Heath paused. “If we also didn’t want it to remain light, slim and easy to carry.”

“It’s very easy to add weight to a product,” cautions Rousseau. “But if you start with a product that’s too heavy, you must start compromising things. So we began by looking at how to build a lightweight rifle.”

The engineers’ first task was to examine where their bolt guns’ weight originates. Since they couldn’t go much lighter on the barrel and the stock, there were really only two other places they could look to, and that was the bolt and receiver. The plan was to design a lightweight receiver and bolt, then they’d think about a magazine and the other improvements.

“An inexpensive way to build a rifle is with a full-body bolt,” Rousseau said. “But I didn’t want to go that way because it adds weight. So we decided on a small-diameter bolt while retaining the three lugs for strength.”

The team was convinced the A-Bolt’s 60-degree bolt throw was an advantage and a selling point, and so it would remain. Yet a 60-degree bolt throw is not as simple as it sounds when used in a compact receiver, and so the X’s bolt was altered slightly from the A’s.

“We had to design the cocking mechanism to hook the striker and compress the firing pin spring. But with the short, 60-degree throw, the ramp that cocks the firing pin as the bolt rotates must be steeper; therefore it requires more force to cock.”

Another obstacle to designing a manageable short-throw mechanism was the team’s desire to eliminate the A-Bolt’s bolt roller—an internal part that not many people know about. It reduces friction and allows easier cocking, but it’s not without its faults, including weight. “Those things don’t age well,” Rousseau said. When I asked for clarification, he said that few people know to oil the roller. So, with the roller removed, engineers had to refine and smooth the X-Bolt’s cocking ramp and mechanism. After they solved it, they moved to the locking lugs.

In order to reduce the size and, therefore, weight of the receiver, the team had to re-organize the locking lugs. Browning wanted a trimmer action that was not as deep, but also insisted it hold four cartridges in the magazine (in standard calibers) while remaining flush with the stock. But to do all that, and prevent the locking lug at the bottom of the bolt from contacting the top cartridge in the magazine as the bolt is rotated, something had to give. The three-lug bolt features a hybrid extractor and a plunger ejector like that of the A-Bolt, but the location of the lugs has changed. Engineers decided to place a small Teflon nodule on the bottom of the bolt that has beveled edges. As the bolt rotates down, the nodule smoothly slides over the first cartridge in the magazine and presses it down very slightly, allowing the bolt to rotate with no chance of steel-on-brass friction.

“Next we looked at magazines. Mannlicher was one of the first to the market with a rotary magazine,” Rousseau said, “and I liked it because it was lighter weight, and because it utilizes more of the space within the magazine itself, its capacity is maximized despite reducing its height.”

“This was important to us, because to carry a scoped rifle a hunter puts his hand underneath the belly, and so I wanted it perfectly flush. The rotary magazine made perfect sense.”

Another advantage of Browning’s polymer rotary magazine is its internal design that retains each cartridge by its case’s shoulder, rather than just floating it in the box supported only by the shell underneath. In this way, rather than slamming the bullet tips into the hard front wall of the magazine during recoil with every shot, the forward momentum of a cartridge in the magazine is arrested by its own shoulder. This is a real, yet rarely mentioned, problem with many magazine-fed guns, especially those with magnum recoil. Riflemen spend top dollar on bullets with the best ballistic coefficients and painfully map their data; having the bullet’s tip get rubbed off or deformed before the bullet is ever fired can negatively affect accuracy, especially at long ranges. The X-Bolt’s magazine remedies this. Its patent was awarded in 2005 under Marcus Heath’s name.

Counterintuitively, Browning engineers say that going with a detachable magazine also adds rigidity to the action. According to Heath, that’s because on the A-Bolt’s hinged floorplate, the bottom of the receiver necessarily had a large cutout in it. The detachable magazine and monolithic, wrap-around bottom metal chassis of the X-Bolt lends its receiver added strength. Also the A-Bolt’s magazine was not a center-feed design, and this proved another area of strength and improvement in the new platform.

“We wanted more material in the bottom of the action, and we knew it would also be good to have a center-feed mag so we could have more material on both sides of the magwell. What resulted was an action that’s about 18 percent more rigid than the A-Bolt’s,” Heath said. “The center-feed design also proved to feed more consistently, as it feeds from only one position, not from both sides.”

Finally, even the magazine’s latch was thoroughly contemplated. While the magazine well is metal so the latch mechanism offers a satisfying, positive click as it snaps in and out of battery, the latch of the polymer magazine is molded into the magazine itself, so when you grasp it and depress the latch, the entire magazine falls out in your hand. This allows the shooter to remove the magazine with one hand, without looking. Still, when this superior magazine debuted on the X-Bolt, folks, including Browning’s own sales force, had doubts.

“We told a few of our reps to stand on it,” Heath said. “We even dared customers to do it too, and then do the same thing with a typical sheet metal magazine. As we knew all along that you can’t bend it or dent it.” These improvements alone lightened the rifle and made it slimmer. But it’s one thing to lighten a rifle, it’s another challenge altogether to lighten it and make it accurate.

“Over the years, I’ve noticed that a rifle can be a lot of things—new-aged, Kevlar-stocked, semi-auto, whatever—but if it isn’t accurate, rifleman aren’t interested,” Heath said. And he’s right.

“Over the years, I’ve noticed that a rifle can be a lot of things—new-aged, Kevlar-stocked, semi-auto, whatever—but if it isn’t accurate, rifleman aren’t interested,” Heath said. And he’s right.

When the goal is accuracy, the obvious place to examine is the barrel, but all the engineers believed they had a great one in the barrels created by Miroku.

“One-hundred percent of Miroku’s Browning barrels are air-gauged at the factory. Every single barrel that makes it on a Browning rifle is honed using a proprietary process and then bore scoped for perfection,” Heath said. “We’ll put them up against anyone’s.” So the team quickly shifted focus on the trigger.

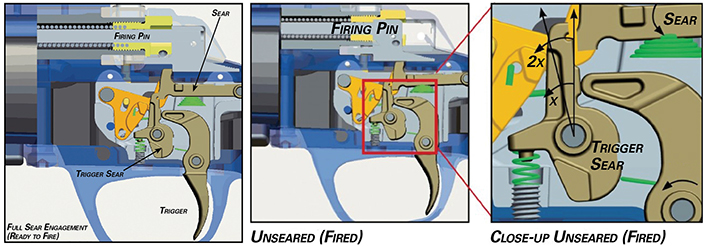

All riflemen—and indeed all manufacturers—must know that a great trigger is essential to accurate shooting, so it’s perplexing to this writer why there are so many poor ones in the marketplace. Certainly, cost is a factor, but it’s not the only one—as evidenced by expensive rifles with sub-par triggers. Browning, however, did not settle for the status quo, and instead decided to go with a three-lever trigger on the X-Bolt because it has the potential to be better; properly made, it minimizes slack and overtravel, while keeping the pull weight light yet safe because of an intermediate lever that multiplies trigger pressure while also maintaining adequate sear engagement. It’s also inherently more difficult to produce, and therefore it’s more expensive.

“At the early stages of development, I went to bat for a three-lever trigger while other companies were looking at the AccuTrigger. My argument at the time was that a good trigger pull will trump secondary safeties on the trigger,” said Cummins, now a Browning product manager who handles the X-Bolt.

What resulted was Browning’s Feather Trigger, and I think it’s one of the best factory triggers, in terms of feel, on the market. It features only 1/16" of total trigger travel with zero creep or overtravel. Like many Browning rifle triggers, it’s gold-plated. Browning claims they come out of the box at 4 lbs. and are adjustable down to about 3 lbs., but the X-Bolts I’ve tried stopped at around 3 lbs., 5 ozs.

Next, the team re-examined the safety. Browning’s U.S. braintrust wanted a three-position safety, as popularized by Winchester, but it felt a center-tang location was better than the Winchester’s side-mounted wing on the bolt’s tailpiece. So it came up with a prototype and had the first X-Bolt made. According to Rousseau, he took the prototype X-Bolt hunting, and shot an elk. But while approaching the downed-but-not-dead animal in deep snow, he couldn’t feel the safety positions well with his numbed, gloved fingers. Somehow in his confusion, excitement and numbed state, he accidentally pressed the trigger and the gun went off. Fortunately, no one was hurt, as the rifle was pointed in a safe direction, but nonetheless when Monday morning rolled around Rousseau assembled his engineers and asked for a new safety system that would allow the three safety positions to be more intuitive; so shooters wouldn’t have to count positions or look at the safety for reference. There were patents issued in the late 1970s pertaining to a “bolt unlock override button” but most of these buttons, opined Rousseau, were located in weird positions. So he challenged the team.

What resulted is perhaps the best and most innovative safety system found on any hunting rifle at this time: Browning bored a hole through the top of the bolt handle’s root, inserted a button and connected it to the trigger via a linkage. The button allows the bolt to open even if the tang safety is in its rearward, or safe, position, and it is intuitive because the shooter can depress it with a thumb as he works the bolt. It’s safe, simple and effective, and now it’s a hallmark of all X-Bolt rifles. Finally, they added a red cocking indicator that is visible below the bolt’s tailpiece.

Now, with the trigger, action and barrel in hand, the team knew to properly bed it in a rigid stock. The single, forward recoil lug of the X-Bolt action is bedded in resin/fiber epoxy. As such, it must be vigorously wiggled to remove from the stock for cleaning.

Finally, Rousseau also felt the A-Bolt’s scope-mounting system—indeed, that of most rifles—could be improved. So instead of drilling and tapping two holes at each end of the action, engineers seized advantage of the X-Bolt’s flat top and ordered a total of eight scope mounting holes. Some scopes are very heavy these days, so doubling the holding power of the bases would prevent heavy scopes atop lightweight, heavy-recoiling rifles from catastrophic failures. Browning’s proprietary scope mounts feature rings and bases as one solid unit; I believe the system is superior to the vast majority of rifles currently on the market.

Putting The “X” In Sexy

Putting The “X” In Sexy

Next, the team faced perhaps it greatest challenge—incorporating all these engineering changes into a lithe, postmodern package that older hunters might appreciate for its performance and new hunters might covet because it’s cool. Again, Browning had some experience in such an endeavor; it had just completed a wholesale evolution of its venerable over-under shotgun line with the introduction of the Cynergy just a few years prior in 2004. Indeed, no story of the X-Bolt rifle is complete without mentioning the Cynergy project from which the X-Bolt concept gained influence.

As Keefe wrote in the aforementioned article: “As the Cynergy is to the Citori, the X-Bolt is to the A-Bolt.” After talking to the X-Bolt’s engineers, however, that influence was perhaps not as prevalent as commonly believed when the new bolt-gun made its debut.

“Cynergy was certainly an influence, especially the aesthetics,” Heath said. Yet Rousseau downplayed it, stressing that the X-Bolt was its own project whose slate contained no preconceived notions of creating a Cynergy rifle.

“We wanted something easy to carry, with no sharp edges.” Like the motorcycles and cars that influenced Rousseau’s design style, he wanted bold lines, sexy, perhaps, but not gaudy.

“We wanted edges and smooth lines that would make sense, but we didn’t want to be too aggressive. Going too radical can drive some customers away. So the X-Bolt was never supposed to be as radical as the Cynergy.”

The prototypes weren’t perfect. For example, its initial checkering pattern extended from the back of the fore-end, along the lines of the bottom metal. Browning had to get rid of it, because in testing it burned the fingers as the rifle recoiled. There were other non-starters.

What finally resulted in 2007 was a rifle that looked radical compared to others of the time, yet was easy to carry, light, trim and had true improvements over the A-Bolt, as well as most other rifles, in general. At least this magazine thought so. In 2008, the X-Bolt won American Rifleman’s Golden Bullseye Award for Rifle of the Year. It was obvious Browning believed in the X-Bolt too, as demonstrated by its frequent line expansions in the years to follow. Product managers such as Cummins are in charge of reading market trends and deciding whether to tweak its rifles to match. For example, long-range shooting and hybrid hunting/target-style rifles are all the rage today; Cummins hinted that it’s not hard to put a heavy barrel (and I assume an adjustable stock?) on an X-Bolt.

As of this writing, Browning offers the X-Bolt in 21 variations and a full array of chamberings. It chambers all the classics, and it’s doing its part in keeping up with the Noslers and Hornadys of the world as they introduce new ones. It’s catalogued 21 special editions. Forty-six versions have already been discontinued for various reasons, mostly due to expired camouflage licenses, industry partnerships or defunct cartridges. Browning has updated the X-Bolt with a few small internal improvements. For example, new versions have a small nylon-tipped, threaded screw that traverses the back left side of the action. It puts slight pressure on the bolt to ensure that it cannot bind, no matter the errant forces placed on it by the shooter.

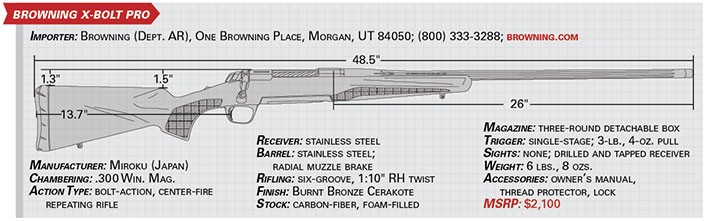

For its latest iteration, the iconic company rolled out what is likely the finest pure hunting rifle to ever be stamped with the Buckmark. It’s called the X-Bolt Pro. Browning worked with a specialty maker to produce a fully carbon-fiber-woven stock that is many times more rigid than wood or polymer, durable and weather resistant, and still lightweight. It’s foam-filled so it doesn’t sound or feel hollow. The Pro features a M13x0.75 threaded barrel for a brake (included) or a suppressor, and its metal is coated in a bronze-colored Cerakote finish. With its fluted bolt, barrel and feathery stock, the Pro weighs 6 lbs., 8 ozs., a stat that puts it in the custom-rifle class at shade more than $2,000. My test model in .300 Win. Mag. shoots sub-inch groups until the thin, 26" barrel gets cooking. All told, based on its performance, features and carry factor, it’s one of my favorite pure-hunting rifles.

Future X

Currently, in 2018, little boys can’t play cops and robbers for fear of getting arrested by the PC police, and heavy two-stage triggers are now considered great in polymer handguns. In this era that’s laden with prime examples of “new and improved” products that ultimately proved to be their undoing, Browning’s vision proved spot-on with its X-Bolt. Today the A-Bolt has been relegated to a classic, and the X-Bolt’s once-radical design is now perceived as normal. Yet I don’t believe this happened entirely due to the X-Bolt’s aesthetics, Browning’s marketing or peoples’ perceptions changing on their own. Rather, as time has told, it’s just an excellent rifle.