A “hun’s head” target was used at the Small Arms Firing School. A specially constructed “trench” range at Camp Perry also presented moving paper mache heads.

At the Small Arms Firing School held at Camp Perry, Ohio, students were issued Model of 1903 Springfield rifles with Winchester A5 scopes.

A century ago, amid America’s entry into the Great War, a who’s who of NRA rifle champions gathered at Camp Perry, Ohio, to conduct the most advanced marksmanship training America had ever seen. Congress had just declared war against Imperial Germany, but the United States found itself totally unprepared; 2 million soldiers were urgently needed, but hardly one-tenth that many were in uniform. And not a single school-trained sniper existed.

Overnight, the Army broke ground on 32 training camps, each to house a division of 28,000 men. After three months’ training, they’d ship out and another 32 divisions would begin training. Meanwhile at Camp Perry, a national-level advanced shooting program was organized—the Small Arms Firing School—where specially selected soldiers would learn advanced marksmanship, culminating in long-range shooting and sniper training. Upon graduation, they’d rejoin their units, instruct their skills to others, and then accompany them to France as intelligence and sniping leaders.

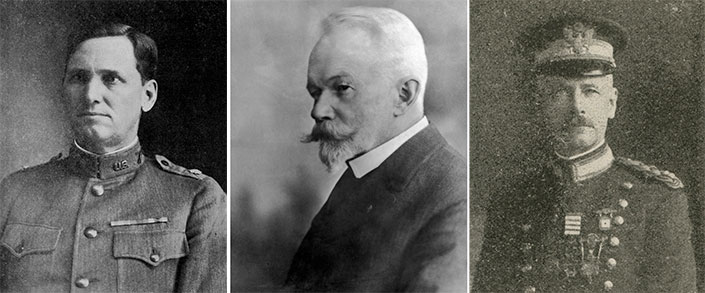

An Impressive Instructor Staff

To call these NRA instructors the best-of-the-best is no exaggeration. Heading Camp Perry’s 50-plus trainers was Lt. Col. Morton C. Mumma, an activated National Guard officer who’d captained the U.S. Palma Team in 1913 and held Distinguished Rifle and Pistol badges.

Directing training was NRA Second Vice President Smith W. Brookhart. An activated National Guard major, Brookhart had led the winning U.S. Rifle Team at the 1912 world championship Palma Match and authored the 1918 handbook, Rifle Training for War. Major Brookhart was also a future NRA president and U.S. senator.

Assisting him was Capt. William H. Richard, the 1903, 1,000-yd. Wimbledon Cup winner, an Ohio National Guardsman and longtime competitive rifleman. As a civilian Winchester employee, during his 24-year tenure, Richard was credited with developing the first heavy-barrel, precision bolt-action rifles.

Perhaps the most prominent instructor was Maj. William A. Libbey of the New Jersey National Guard, who also was president of the NRA. A professor of geography at Princeton University, Libbey had twice explored the arctic with Adm. Robert Peary, and counted among his personal friends President Woodrow Wilson, with whom he often spoke. Major Libbey twice had shot with the U.S. Olympic rifle team, winning a silver medal at the 1912 Olympics. At Camp Perry, Libbey would oversee the long-range shooting phase of sniper training.

Captain William Leushner, another Olympic rifleman, won a gold medal at the 1908 Olympics, and took home one silver and two bronze medals he earned at the 1912 games.

Captain James H. Keough, a Distinguished Rifle badge recipient, had shot with the U.S. Rifle Team at the 1908 NRA championships, where he took top place in the 400-yd. event. Two years later, he won the International Smallbore matches.

A three-time Indiana State Rifle champion, (1905-1907), Capt. Herbert W. McBride, was a Distinguished Marksman graduate of Britain’s Hythe School of Musketry. As an American volunteer sniper, he fought with Canada’s 38th and 21st Battalions in France; decorated for bravery thrice, McBride was also wounded three times. Discharged due to his injuries, he was commissioned by the U.S. Army to instruct at Camp Perry and later authored the sniping classic, A Rifleman Went to War.

Another instructor, NRA director and competitive rifleman, Capt. Edward C. Crossman, authored two post-war classics, Military and Sporting Rifle Shooting and The Book of the Springfield. In the 1920s and ’30s, Crossman often wrote for the NRA magazines Arms And The Man and its successor The American Rifleman (the name was changed in 1923).

“For the first time in the history of this nation,” the NRA magazine, Arms And The Man editorialized, “there is in the service of the United States today the flower of American marksmanship.”

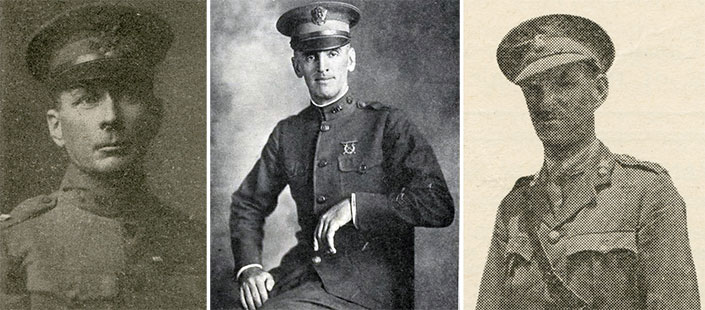

Despite their extensive shooting knowledge, however, the NRA instructors lacked modern sniping experience. This battle know-how was supplied by British and Canadian sniping veterans posted to Camp Perry to assist them. They were led by British Maj. Ernest Edward Godfrey, who’d been severely wounded at Gallipoli, Turkey, in 1915. Recovering, he later served as a battalion sniping officer on the Flanders Front, and then instructed at the British 2nd Army School of Sniping, Observation and Scouting.

Major Godfrey’s detachment included two British lieutenants—Archibald Robert Hall and J.W. Wright—along with two Canadian lieutenants—James A. McKenzie and Hugh Aird. All had been wounded in battle. The team’s non-commissioned officers were led by Sgt. Frank Crossland of Canada’s 60th Infantry Battalion.

The Course Of Instruction

While each of the Army’s 32 training camps had some form of sniper training, Camp Perry’s was a national-level school, bringing in officers and enlisted men from all across the country. Instructing 100 to 500 students at a time, the Small Arms Firing School’s goal was to produce unit-level marksmanship and sniping experts, to both teach and lead scout-sniper and intelligence platoons. Enlisted students would be commissioned as second lieutenants upon graduation.

Six cycles were scheduled, each running 30 days, and taught in three phases: five and one-half days for basic rifle instruction; two weeks of range firing out to 600 yds.; and a final week focused entirely on sniping, with shooting to 1,000 yds. using scoped rifles. Impressively, of the 30 days, some 22 would include live-fire training.

While the NRA trainers focused on advanced marksmanship training, Maj. Godfrey’s Canadian and British instructors taught sniping tactics and techniques. Not to be desk-bound, Maj. Godfrey personally conducted classes on aerial photography, scouting and military intelligence.

Likewise, American Maj. Brookhart personally instructed on the U.S. Army Model 1917 and 1918 Musketry Rules, devices much like a slide rule that employed milliradians or “mils” to calculate range—similar to today’s mil-dot reticles. In fact, these devices used the same mil formula, which was engraved on them as a handy reference.

Major Libbey oversaw range practice, which incorporated, “long-range practice, practice with telescopic sights, estimating distances, and target designation.” During sniper training, the students fired on a special range constructed with guidance from the Canadian and British staff. Just like the sniping schools in France and Britain, Camp Perry had a simulated “No Man’s Land,” with burned out vehicles, barbed wire obstacles, craters and “German” and “Allied” facing trenches. As Arms And The Man described it in 1918: “The firing line on Maj. Godfrey’s range is a line of trenches, off which sniping posts are sunk under the parapets. Here the student officers are taught to build and conceal loopholes, from which a deadly fire can be directed against enemy trenches, which rise something under 200 yards away, divided from the ‘Ally trenches’ by realistic barbed wire entanglements.”

Captain Crossman, who went through the British-Canadian sniper training, provides more detail: “With our scope-sighted rifles, hidden in some sniper emplacement along the British trench, we who were taking the course were supposed to watch until a cautious Hun figure appeared in some broken portion of the German trench, or peeped over the parapet, [and] were supposed to spot him, and to fire in the second or two of exposure.”

A visiting journalist watched the students firing at moving targets: “The ‘Germans’ are paper mache figures attached to moving rods traversing the trench lines. At some points the heads of the Germans rise for a moment above the trenches. The mechanism is so arranged that they seldom are disclosed at the same place twice. But the Americans, lying in their snipers’ pits, seldom miss a shot.”

Several times, national media visited the school, one visit resulting in a headline in the Washington Herald newspaper, “Yankee Snipers Receive Praise from Britishers on Rifle Marksmanship.” When the reporter asked how well the Americans were shooting, a British trainer said, “top hole,” which the writer explained, “… is a somewhat slangy way of conveying the idea that the Yanks are hot stuff.”

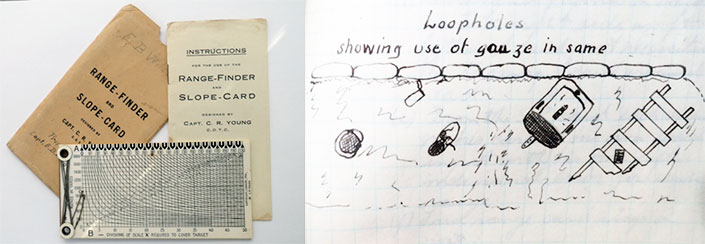

While researching for my new book on World War I sniping, I discovered the course book and handwritten notes from one student, U.S. Army Capt. E.B. Wilson. Illustrative of the quality of instruction at Camp Perry was the class dealing with “Sniping Posts” as taught by British Lt. Hugh Aird. Captain Wilson dutifully sketched the variety of such sniping positions and took excellent notes.

Among Wilson’s training materials I found a surprisingly sophisticated “Range Finder and Slope Card.” Not only did this yield fairly exact ranges, but it tells us that World War I American snipers considered compensation for uphill/downhill angles when shooting—a factor all but ignored by snipers for the next 60 years.

The 1918 National Matches

The Small Arms Firing School’s final cycle finished just before the 1918 National Matches, slated to be held at Camp Perry. Instead of closing down, the War Dept. had the school’s cadre remain there to provide training to the civilian and military competitors. The arriving shooters were issued the same rifles as the earlier students and supplied with ammunition.

The attendees sat through indoor classes—including British Maj. Godfrey’s presentation on sniping—and then, supplied with Springfield rifles topped by Winchester A5 scopes, went through live-fire training. Just as the earlier students, they shot to 1,000 yds. and afterward competed in the National Matches.

Two weeks later the Small Arms Firing School closed down, and its cadre was transferred to Camp Benning, Ga. There they were joined by instructors from the Army School of Musketry at Fort Sill, Okla., and became the newly created Infantry School of Arms. Major Brookhart, promoted to lieutenant colonel, was appointed director of the Infantry School’s Marksmanship Department, which included a sniping section with its own assigned instructors.

Shortly thereafter, the November 1918 Armistice was declared and demobilization would soon follow. Arguing to keep the NRA trainers on active duty, an editorial in the NRA magazine pleaded, “To send these men back to private life would be a fatal mistake.”

But demobilization was inevitable. Twelve months after the Armistice, U.S. Army strength dropped from 3.25 million to 224,000, and later to just 147,000. The post-war Army had no room for 40-year-old captains and 60-year-old majors, no matter their marksmanship knowledge. A dozen Camp Perry instructors were detailed to the Ordnance Corps to inspect rifles for long-term storage, another dozen was discharged. The rest soon went back to civilian life, replaced by a smaller staff of career soldiers.

The Camp Benning Infantry School continued sniper training in 1919 and, according to a July 27, 1919, New York Times article, dispatched a sniper demonstration team to the National Matches at Caldwell, N.J. The Times hailed the demonstration as a “feature attraction,” that proved especially popular with the public. Despite such attempts to promote Army snipers and sniper training, high-level interest waned and then funding went away. After 1920, there were no newspaper mentions of the sniper school or any military sniper training anywhere in the United States, Canada or Britain.

For a short while, competitive rifle shooters kept alive an interest in sniping. The 1921 NRA matches included a sniping-related, “Special Telescope Match,” with participants firing heavy-barrel Springfield rifles topped by A5 Winchester scopes. Marine Sgt. J.W. Adkins won the match, placing 80 of 100 shots in the 36" bullseye at 900 yds., and 91 of 100 shots at 1,000 yds.

A “Sniper Match” was also featured at the 1922 United Services of New England Matches, where Marine, Army and National Guard rifle teams shot at a 200-yd.-wide simulated village with pop-up and moving targets. Although the Sniper Match proved “popular beyond all expectation,” there appears to be no further record of this match, or any sniping-related match held anywhere. Everything related to sniping simply went away.

Thus, during World War II and the Korean and Vietnam Wars, necessity would demand the temporary rebirth of sniping, paying in blood for the knowledge that had been abandoned in the past.

As for the Small Arms Firing School, that name and the concept of training shooters attending the National Matches at Camp Perry did not end. So well-received was that effort that it has been a tradition ever since. Today the Small Arms Firing School is instructed by the U.S. Army Marksmanship Unit from Fort Benning, Ga., and is as well-received and worthwhile today as it was 100 years ago.

Sniping In The Trenches

Sniping In The Trenches

The author has just completed his latest book, Sniping in the Trenches: World War I and the Birth of Modern Sniping from which this story is excerpted. Major Plaster is also the author of The Ultimate Sniper as well as The History of Sniping and Sharpshooting, the latter being, hands down, the finest and most comprehensive work on the subject to date. But Maj. Plaster has continued to find more information on snipers and sniping since the latter was published. The result is a book covering the rifles, optics and ammunition, plus the training and tactics used by both the Allies and the Germans during the Great War.

From France and Flanders, to Gallipoli and the Meuse-Argonne Offensive, there is detailed information on men—the snipers themselves—that has not been reported on in decades, and certainly not in one volume. Too, firsthand accounts are included from American, British and Canadian snipers. The 8 1/2"x11" hardbound, 280-pp. book contains nearly 500 photos and is available from Paladin Press (paladin-press.com). The price is $40 plus shipping. www.ultimatesniper.com

—Mark. A. Keefe, IV, Editor In Chief