It’s hard to believe an entire decade has passed since Hornady Mfg. of Grand Island, Neb., introduced the 6.5 mm Creedmoor cartridge. Since 2007, interest in the cartridge has increased steadily, a slow-burning fuse that in just the past two years has ignited an explosion of 6.5 Creedmoor-related product offerings—from loaded ammunition and components to Creedmoor-chambered firearms—many of which are targeted toward the hunting and even tactical shooting segments, despite the cartridge’s original role as a long-range competition load.

So, what makes this metric loading so appealing to American shooters who have long been enamored with classic .30 calibers? And where does the 6.5 mm Creedmoor fit in the battery of traditional American sporting cartridges? I first took interest in the cartridge four years ago, a little late for “early adopter” status, but still ahead of the mainstream, and these are the questions I found myself asking as the ground began to shift and the Creedmoor’s popularity erupted. What I found was not only a versatile and performance-driven product, but also a case of right time, right place and, most importantly, right people.

Movers And Shakers

Parameters for a new precision cartridge were conceived by veteran High Power competitor Dennis Demille. Precision rifle shooting, and accuracy in general, has much to do with consistency, uniformity and repetition—whether in physical action or the construction of loaded ammunition. It’s understandable then, that by the 2005 National Matches at Camp Perry, Ohio, Demille had taken a dim view of the wildcat loads prevalent in across-the-course shooting competitions, and their inherent inconsistencies—in recipe, construction and, ultimately, performance. (Interestingly, despite his dissatisfaction with his own 6XC ammunition, Demille nevertheless shot that wildcat to victory, becoming the 2005 NRA High Power Champion with a score of 2385-119X.)

As is often the case, it’s not always what you know, but who you know, and for Demille the who was good friend and senior Hornady ballistician Dave Emary. Fortuitously, the two were sharing a condo during service rifle week at Camp Perry. During the matches, Demille formulated a list of requirements for his ideal High Power competition cartridge:

• Be magazine-length for use during the rapid-fire string in competition.

• Have significantly less recoil than the .308 Win. to enhance performance during rapid-fire strings, and for general shooter comfort.

• Shoot flat with accurate, high-ballistic-coefficient bullets.

• Promote good barrel life.

• Use readily available components, including powder, so that it can be easily replicated.

• Include the reloading recipe and data on the packaging of production loads.

• Be manufactured in sufficient quantity to meet demand.

Requirements in hand, Emary returned to Hornady and assembled a team to make the wish list a reality. Emary, Joe Thielen—another crack engineer at Hornady—and then-sales and marketing manager Neil Davies became the cartridge’s prime movers, but according to Davies, the effort really began as an internal “black op.” So, while the co-conspirators had a mission and the horsepower to carry it off, they still needed formal approval to launch the project. In what was described to me as a Benjamin Franklin-esque “hang together or hang separately” moment, the team made its case to the boss, Steve Hornady, and according to Davies, “He said ‘yes’ on the first ask … he never says ‘yes’ on the first ask.” Officially sanctioned, Hornady’s new long-range precision cartridge was well underway.

Components And Contenders

One of the first decisions that had to be made in the cartridge’s development was the diameter, or caliber, of the intended projectile. It probably wasn’t a hard decision for Emary, considering his opinion that, “You absolutely cannot beat the aero-ballistic performance of 6.5 bullets, if they are done right.” So, the team would build around a 6.5-mm (.264-cal.) bullet. This wasn’t the safest bet, considering metric loadings are far more popular in Europe, and 6.5 mm anything has traditionally been a tough sell in the States. Still, there is no denying the capabilities of the caliber, or its long military and sporting pedigree.

For the new cartridge’s case, the Hornady team turned to the then-new .30 T/C cartridge. A joint venture between Hornady and Thompson/Center, the .30 T/C took advantage of a short, fat cartridge case—a profile known to burn propellant more efficiently, and thus improve performance, compared to tall, skinny cartridges. In this way, the .30 T/C uses a case that is shorter (though slightly wider) than the .308 Win. to achieve .30-’06 Sprg.-like ballistics, but with far less recoil than either of those popular .30s. The .30 T/C saw little commercial success, but was nevertheless an important stepping stone, and the ideal parent case for the 6.5 mm Creedmoor. Like the .30 T/C, the 6.5 would seek to maximize efficiency and performance, while also maintaining a relatively trim profile and reducing recoil.

It’s worth detouring here to address another cartridge that many believe could have influenced the 6.5 Creedmoor’s design—the .260 Rem. Officially introduced in 1997, after a long history as a wildcat, the .260 Rem. is simply a .308 Win. case necked-down to accept a .264-cal. (6.5 mm) bullet. In many ways, given the case capacity and projectile diameter, the .260 would seem to be an easy plug-and-play solution to Demille’s original cartridge requirements. To this day, Demille and Emary both receive numerous inquiries regarding the merits of the .260 Rem. compared to the 6.5 mm Creedmoor, and Emary was kind enough to share with me his thoughts on the matter, which I paraphrase here.

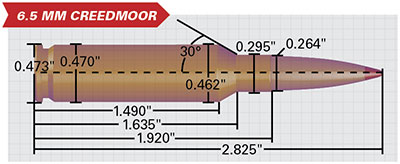

The basic problem is the different roles for which the two cartridges were developed, and the bullet styles best-suited to fulfill those roles. The .260 Rem. was always intended to be a sporting cartridge, and was designed to maximize case capacity behind 120-gr. to 140-gr. hunting-style bullets. In this role, it really does excel. However, it possesses a few characteristics that limit its potential for long-range precision shooting. First, the .260’s case has a lot of body taper and a relatively shallow shoulder, qualities that can introduce a small degree of principal axis tilt—misalignment between the projectile and bore. Also, the .260 has a comparatively short neck, a quality that causes longer, heavier bullets—like those preferred for precision shooting—to be seated deep inside the case, which in turn decreases the space available for propellant. By contrast, the 6.5 Creedmoor case has minimum body taper and a 30-degree shoulder which helps the cartridge “center up” inside the chamber. Too, it has a longer neck, meaning heavier bullets, including Hornady’s javelin-like 147-gr. ELD Match, do not encroach as far into the case.

Don’t misunderstand, the .260 Rem. is not an “inaccurate” design. Indeed, it can be superbly accurate, and I’m sure there are readers right now measuring groups to prove that case. It’s even worth mentioning that Sgt. Sherri Gallagher, USA, won the 2010 NRA High Power championship with the .260 Rem. (2396-161X). But the fact is, the .260 was not originally intended for long-range precision shooting, and therefore the overall design was not optimized for accuracy at extended ranges. The 6.5 Creedmoor, on the other hand, was designed exactly for that pursuit.

Early Adopters

In 2006, Emary was ready to show Demille the initial designs, and in 2007 Hornady officially introduced the 6.5 mm Creedmoor cartridge—so named both for Demille’s long-time employer, Creedmoor Sports, and for the historic Creedmoor range in Long Island, N.Y., where the first national rifle matches were held. Two loads were initially produced, pushing 120- and 140-gr. A-Max bullets at around 2,900 f.p.s. and 2,700 f.p.s., respectively. And, yes, the recommended reloading data was printed on the box’s label.

The first gunmaker to adopt the 6.5 Creedmoor in a commercial offering was DPMS, then helmed by Dustin Emholtz and Randy Luth, and the gun was an AR-10-style rifle. Davies fondly recalls that so strong were the personal relationships involved (again, the right people) that DPMS agreed to build rifles after “only one phone call.” Ruger followed very shortly after, and was the first large-scale manufacturer of 6.5 Creedmoor-chambered guns, first introducing an M77 Hawkeye Varmint Target rifle which featured a heavy-contour 28" barrel, followed by a No. 1 Varminter model. Of course, smaller makers and custom shops, especially those catering to the competition crowd, were also fast out of the gate with 6.5 Creedmoor offerings, and the early success of the new cartridge was writ large on the score sheets of countless rifle matches.

Despite storming the competition circuits, the 6.5 Creedmoor failed to win widespread acceptance by American hunters during its first years of production. It’s worth noting that the cartridge received some help in that department when Hornady introduced its Superformance line of ammunition, which included a 6.5 Creedmoor load topped by a 120-gr. GMX bullet with a published velocity of more than 3000 f.p.s. The monolithic GMX bullet—originally gilding metal, now a copper alloy—proved to be a heavy-hitter, providing reliable expansion and deep penetration thanks to its polymer tip and solid construction. The 6.5 Creedmoor and GMX combination was confidence-in-hand for the sportsman who chose to venture afield with the precision penetrator, and stories began to circulate more frequently about the fast little Hornady cartridge that punched far above its weight class—a lesson European hunters had learned about 6.5-mm projectiles many decades before. Yet, despite growing adoption by hunters “in the know,” convincing American sportsmen to trade in their trusty .30s remained a daunting challenge.

So, what did the early adopters see in the 6.5, and how did the Creedmoor stack up against the American sporting workhorse .308 Win.? In short, the Hornady cartridge was not only supremely accurate, it was also just plain miserly with regard to retaining velocity, and therefore energy, at extended ranges. It’s very hard to make an apples-to-apples comparison between the 6.5 and .308, but a fair measure might be to examine the performance of two loads developed by Hornady for a common purpose. For such an example, I looked to Hornady’s Precision Hunter series, a line specially formulated to provide best-in-class ballistic and terminal performance at any range, especially on those longer pokes. The selected loads both utilize heavy-for-caliber ELD-X bullets—143-gr. for the 6.5 load and 178-gr. for the .308. Introduced in 2015, the ELD-X, Extremely Low Drag-eXpanding, bullets were designed to possess very high ballistic coefficients, provide reliable expansion at all practical hunting ranges, and feature Hornady’s new Heat Shield Tip—an improvement over earlier polymer bullet tips which, Doppler radar testing revealed, just couldn’t stand up to the heat of supersonic travel (January 2016, p. 66).

The comparison uses Hornady’s published load data for Precision Hunter ammunition, and the results (p. 61) were generated by the company’s Doppler radar-based 4 Degrees Of Freedom (4 DOF) ballistic calculator. At first blush, the data reveals two very good sporting loads that shoot very flat for caliber and do a good job retaining lethal velocity and energy beyond 400 yds.—well-beyond, considering the ELD-X payload. But the real revelation comes around the 600-yd. mark, where the 6.5 Creedmoor is still handily outpacing the .308 Win., the energy gap has closed to less than 50 ft.-lbs. and the bullet’s trajectory, how far it “drops” at a given distance, turns decidedly in the 6.5’s favor. Beyond 600 yds., it’s not even a question, the 6.5 Creedmoor is the superior load in terms of velocity, energy and trajectory—there is nearly a 2½-ft. difference in drop at 800 yds.

If the cartridge’s ballistic capabilities were not enough, there was also the 6.5’s huge advantage in shootability. Remember Demille’s original request for a cartridge with significantly less recoil than the .308 Win.? That challenge was accepted and met in the 6.5 mm Creedmoor. Mark Gurney, an engineer and product manager for Ruger reported, “In one of our very first trips to FTW we had an M77 Varmint Target rifle in 6.5, and the FTW guys were so amazed at how easily anyone could get behind it and bang steel at 1,000 yds.” For those who don’t know, FTW Ranch is a renowned precision rifle marksmanship school, home to the Sportsman’s All-Weather All-Terrain Marksmanship (SAAM) training course, and anchored by a cadre of instructors who are not only highly experienced shooters, in their capacity they also spot for thousands of long-range rifle shots each year. The reason they observed that “anyone” could ring steel at 1,000 yds. is due, probably in equal parts, to the cartridge’s own inherent accuracy, its excellent ballistic performance with a good .264-cal. bullet, and it’s soft-shooting nature which does much to calm nerves, avoid flinches and generally promote consistent, accurate shooting.

Accuracy And Accessibility

By 2013, when I first starting taking interest, the 6.5 mm Creedmoor had earned accolades on the firing line and was steadily gaining recognition as a sporting up and comer. At the same time, within the hunting and firearm industry there was a movement afoot that, I believe, greatly influenced the pace of adoption for the 6.5 Creedmoor—the bargain bolt-gun boom. With Ruger’s American Rifle leading the charge, economically priced bolt-action rifles began sweeping the market—a market, by the way, that was already quite lively due to the country’s political climate. At the time, my fellow editors and I had a running joke when addressing pricier firearms, “For that price I could just buy three Ruger Americans.” It was a great time for the cost-conscious American consumer, and an excellent opportunity for shooters to try new cartridges with minimal investment. Such an environment should have been a boon to the 6.5 Creedmoor but, unfortunately, that chambering was not among the initial offerings. That was soon to change.

In 2014 Ruger released the Predator line of American rifles, which included a 6.5 Creedmoor option, and in 2015 the Ruger Precision Rifle made its debut (August 2015, p. 50). An affordable, range-ready, fully adjustable chassis-type rifle, the Precision was not only offered in a 6.5 variant at launch, that chambering was the headlining act. The effect these two introductions had on the life cycle of the 6.5 Creedmoor cannot be overstated. The Ruger Precision was a hugely successful product launch that provided American shooters an affordable entry point into the world of long-range precision shooting and competition—a world, of course, dominated by the 6.5 Creedmoor. And for shooters who wanted to parlay the cartridge’s performance into a hunting application, the American Predator, too, offered affordable accessibility.

The past two years have seen an unprecedented explosion of 6.5 Creedmoor-related products. Offerings from every major manufacturer of ammunition and firearms are represented, and every conceivable price point and configuration is covered. And though the chassis rifle craze has cooled just a bit, a new class of hybrid, adjustable rifles is emerging. Guns such as Bergara’s B-14 HMR (Hunting and Match Rifle) blend precision-oriented technology with traditional hunting aesthetics to achieve a “best of both worlds” solution for the range and field. And according to my industry contacts, the 6.5 mm Creedmoor is the most popular option for these new guns.

It’s funny, when I first decided to write this article, almost two years ago, I intended to include a catalog of companies building product for the 6.5 Creedmoor. Now, everybody has skin in the 6.5 game, and the list of non-participants would probably be shorter. Conveniently, though, the near-universal adoption lends credence to a phrase that came to mind more than a year ago, as I planned to commemorate my favorite cartridge’s decennial anniversary—the 6.5 mm Creedmoor truly is “An overnight success, 10 years in the making.”

Accuracy Afield

I didn’t have to hunt the Kalahari to prove the accuracy, power and versatility of the 6.5 mm Creedmoor cartridge. A decade of dominance on the Precision Rifle Series and High Power circuits stands as evidence, and range work aided by chronographs and Doppler radar can detail just how stingy the .264-cal. bullet can be in terms of shedding velocity and energy. But there was perhaps no better way to illustrate the 6.5’s capability as a serious sporting load than to pit it against the Dark Continent’s diverse non-dangerous game species, with a focus on accurate, extended-range shooting, and terminal performance against the likes of zebra and blue wildebeest, long held to be some of the toughest of Africa’s plains game.

For the hunt, I chose to shoot Bergara’s Premier Series Stalker rifle topped with a Leupold VX-6HD 3-18X 44 mm scope. The rifle features a premium 22" barrel, a carbon-fiber stock and Bergara’s own Premier Action, and the scope was quintessential Leupold—excellent glass, precise adjustments, rugged construction and, of course, American manufacture. Together, the rifle and scope made for a handy package, weighing just more than 7 lbs., and it proved to be one of the most accurate combinations I’ve ever laid hands on, but more on that soon.

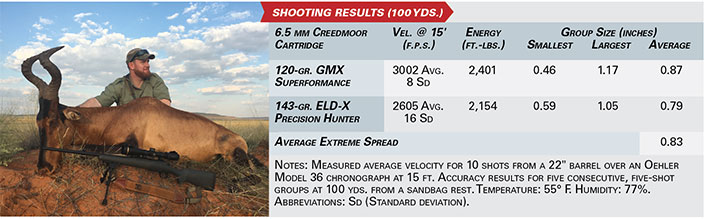

For ammunition, I consulted with my hunting partner, good friend, and one of the original Creedmoor conspirators, Neil Davies of Hornady. Happily, we were in agreement that two types of ammunition should be taken: 120-gr. GMX Superformance for the bullet’s durable construction and penetration capability on tougher and larger game, and 143-gr. ELD-X Precision Hunter for extended-range performance. Prior to the hunt, I ran both loads through the American Rifleman accuracy protocol, and was incredibly satisfied with the results. Averages for five consecutive, five-shot groups at 100 yds. were 0.87" for the GMX and 0.79" with the ELD-X, giving my rifle and hunting ammunition an overall accuracy average of 0.83". Better still, fired from the Bergara, both loads grouped at the same point of impact at 100 yds. Such performance is nearly unheard of, and you can be sure I have no plans of parting with that rifle.

Davies and I traveled to the southern portion of the Kalahari Desert in South Africa’s Northern Cape to hunt with Chapungu-Kambako Safaris (chapungu-kambako.com) out of its Kalahari Oryx lodge. Distinguished by high daytime temperatures and rolling dunes of sugar-fine red sand, the region is home to a diverse population of African plains game. The dunes, in particular, offer hunters a unique challenge—both concealing game in their folds, and providing observation points over vast expanses of land. It was the perfect opportunity to test the 6.5 Creedmoor in the wide open.

Though we didn’t intend to pass up a Kalahari trophy, Davies and I weren’t hunting for horn. Instead, we asked the professional hunters guiding us to give us their tired, their poor and their non-reproducing specimens for harvest, and our success would be measured in data points—information like shot distance, and notes about observed terminal performance—and our trophies would be recovered bullets.

A week of hunting yielded more than a dozen successful harvests, and, as passionate outdoorsmen, Davies and I were both proud and relieved that—thanks to good shooting and excellent bullet performance—not a single animal was left wounded, or even had to be tracked.

My shots ranged from 100 yds. to 515 yds., with an average of 280 yds. The species taken included springbok, red hartebeest, oryx (gemsbok), a blue wildebeest and a Burchell’s or common zebra. Generally, I used the 120-gr. GMX on the hardier game, including the wildebeest and zebra, and kept those shots within 200 yds. to ensure good penetration and reliable expansion—both of which are facilitated by higher velocity. Shots beyond 200 yds. were the realm of the 143-gr. ELD-X, which has the endearing characteristic of expanding reliably at virtually any hunting distance. Results with both bullets were fantastic, and I’ve included a sampling of data and recovered projectiles to illustrate their performance. Missing from my larger collection are most of the GMX bullets, which generally passed through their targets and were unrecoverable.

As the hunting drew to a close, Davies and I gave our professional hunters, as well as the property manager and his teenage son, the chance to shoot the Bergara and experience the 6.5 Creedmoor. To a man, each rose from the bench smiling and marveling at their own accurate shot placement. They were amazed that such a soft-shooting cartridge was capable of producing a through-and-through, one-shot harvest on a zebra. Immediately inquiries were made about how they could get their hands on a Creedmoor-chambered gun. It was a great experience, and a testament to the virtues of the 6.5 mm Creedmoor.

—J.L. Kurtenbach