Stephen Hunter’s G-MAN will be on sale May 16, 2017. (Published by Penguin Random House)

Isn’t much. Not a thing, really. Just a boulder stuck horizontally in a patch of grass that extends, like a peninsula, into a parking lot fronting a bland municipal building. If you look carefully, you’ll notice a brass plaque on the boulder, with brass names and then brass words in the stentorian “official” prose of commemoration that seems hollow so many decades after.

This unprepossessing arrangement, under a vault of trees in a far suburb of Chicago called Barrington, offers little to please the eye or appease the heart. Few journey to see it. I am one who did.

Because the boulder in the parking lot marks hallowed ground. At this spot, on Nov. 27, 1934, two federal agents and two professional criminals fought what may have been the most savage gunfight in American history, short of military combat. Of the four, three had automatic weapons, the fourth a short-barreled, semi-automatic 12-ga. riot gun, plus assorted handguns of the .38 Super and .45 ACP variety. All that firepower means that it was certainly more intense than the fabled “Gunfight at the O.K. Corral,” fought with single-action revolvers and one double-barreled shotgun; it was probably more intense (though it’s a tough call) than the FBI Dade County shootout of 1987 where no automatic weapons were involved, only one semi-automatic rifle (a Mini-14), one short-barreled pump shotgun and the rest duty handguns.

When it was over, after only a few minutes by the clock and what must have seemed an eternity by the participants, one man lay dead and two more were dying. That’s what it cost to bring down Baby Face Nelson.

It’s been my privilege to examine this event for a book project. My intrepid researcher, Lenne P. Miller, used the Freedom of Information Act to obtain documents from the FBI that were used in preparation for the trial of the lone criminal survivor, and from them we’ve confirmed some legends, destroyed some others and uncovered facts either not widely known or never published. For the first time, I believe we can say with near certainty which gun Nelson charged his FBI opponents with, a fact as yet untethered in history.

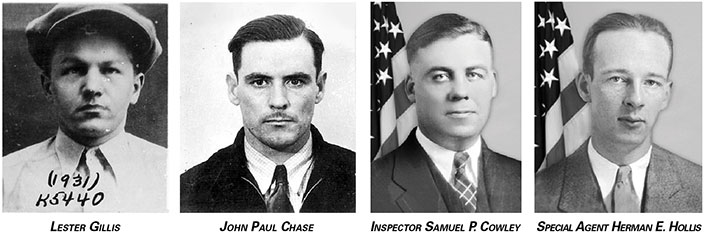

“Baby Face” was an American, Chicago-born. He had a real name: it was Lester Joseph Gillis, and he was 25 years old, and there was nothing conspicuously infantile about him. Not particularly diminutive by 1934 standards—lithe, supple, always snappily dressed and rather handsome—he reminds me of Mickey McGuire in the “Our Gang” comedies, later to become well-known as Mickey Rooney (an irony since Rooney played Baby Face in a forgettable ’50s B picture). He was certainly a contender for the title of most violent criminal of 1934. That would be some title: 1934 was the year of gunfights, an anomalous year when motorized, heavily armed bank robbers such as John Dillinger, Pretty Boy Floyd, Clyde Barrow and Homer Van Meter enjoyed the temporary leverage afforded by high-speed vehicles and state-of-the-art infantry arms. A law enforcement entity hamstrung by lack of radio communications and archaic jurisdictional laws proved to be no match. The motorized bandits spread terror, made money and had a hell of a good time doing it, while enjoying outlaw celebrity, booze, nightclubs, the track, even ball games, all in the company of good-looking women. They were rock stars, basking in the vicarious enthusiasm of a country wracked by bitter Depression.

But all of them, clearly, were sane men, rationalists weighing risk against benefit, daring bullets, prison and death for dough and dames and fame, with dreams of retirement to Tijuana. Les—as I will call him, as did his loving wife Helen and his sidekick to the end, John Paul Chase; only the newspapers called him “Baby Face”—was the anomaly within the anomaly. A conspicuous teetotaler, he didn’t like nightclubs or dames; he loved pretty little Helen and his mom and his two kids, Ronald and Darlene. He was Ozzie Nelson. But he was Ozzie Nelson with a machine gun. What set him apart from his confreres was his unquenchable taste for violence. He rode a wave of anger—as a child in a tough, crime-ridden West Side neighborhood called “The Patch,” he watched his drunken father beat his mother, and learned to despise power and authority at the toe end of a boot—to a kind of queasy pop culture immortality, and his name to this day conjures insane violence.

Put the Thompson in his hands and he became something frightening to behold, much less confront. He had no compunction about pulling the trigger. He had already killed one federal agent—W. Carter Baum, whose name is on the plaque along with that of Samuel P. Cowley and Herman “Ed” Hollis, the FBI agents who ended Les’s run at the cost of their own lives. Perhaps as telling, Les turned his Thompson loose on downtown South Bend, Ind., on June 30, 1934, during a botched bank robbery. Imagine: someone in downtown Middle America, on a bright summer Saturday morning, at the corner of streets called Michigan and Wayne, pulling the trigger on General Thompson’s “trench broom,” sending 50 .45 ACPs out in the general vicinity of everywhere. Only by God’s grace and the luck of the Irish did no one die from this insane fusillade.

But by November, it was winding down. The Justice Department’s Department of Investigation—it didn’t become a bureau until 1935—had shot and killed both Dillinger (in July) and Floyd (in October); Homer Van Meter, a deadly rifleman who’d killed a police officer at South Bend, had been Thompsonized by St. Paul detectives in August. Of the all-stars, only Les remained, now risen (to his satisfaction) to the rank of Public Enemy No. 1. The Division, meanwhile, had learned its trade fast, since the debacle at Little Bohemia in April, where it had all of the bank robbers cornered and let them all escape, while killing a local man and wounding another and losing Agent Baum to Les in the process. And after Baum, the division wanted Les badly.

Through sophisticated national investigation, labor-intensive gumshoe work, plus “tips” from “mysterious sources”—possibly organized crime elements—the agents had learned Les was planning to winter at a shut-down resort in Lake Geneva, about 50 miles north of Chicago. Its owner, a minor crime figure, turned like a leaf in a storm on Les, and agents moved in to set the ambush. However, Les, being somewhat spontaneous in his movements, showed up early, catching the Division boys unprepared. Les recognized what was about to happen from the postures of two stern men in topcoats and suits standing in the doorway of the owner’s home, and Chase gunned the brand-new—that is, freshly stolen—Model A Ford down the road and headed out. Tragically, one of the agents left behind was the FBI’s best gunfighter, Charles Winstead, a fearless cowboy-boot-wearing Texan who had put the fatal .45 into John Dillinger five months earlier. He would be out of the fight that day.

Here is one of the unanswered enigmas of November 27: as Les, Chase and Helen pulled off the dusty road to the inn and back on the main highway, they could easily have veered north, deeper into Wisconsin toward upstate Michigan, west to Iowa or beyond, east toward Milwaukee and then the northern suburbs of Chicago. Any of those choices would have rendered them virtually olly-olly-in-come-free. Instead, they linked up with U.S. Route 12 (now 14), called Northwest Highway, for a straight-line vector into the heart of Chicago. It was the most obvious thing they could do, and one has to wonder why on earth someone as skilled in the arts of escape and evasion as Les Gillis would choose that path. What compelled him to risk everything and head for Chicago? We may never know.

Winstead sent one of the other agents to the main lodge where he called the division’s Chicago field office on the 19th floor of the Banker’s building with the car description and license number. Why Winstead and the other two agents—only a few minutes behind and heavily armed—didn’t pursue down Northwest Highway is another unanswerable question. Their arrival in Barrington would have changed the outcome of that day radically.

It would be satisfying to report that in Chicago 50 agents immediately loaded up with Thompsons and bulletproof vests and took off on safari. Instead, the office was all but deserted, staffed only by Inspector Sam Cowley, basically the agent-in-charge (though the chain of command was muddy as most thought celebrity agent Melvin Purvis was calling the shots), Special Agent Herman “Ed” Hollis—another of the three Dillinger shooters—and a few others.

It would be satisfying to report that in Chicago 50 agents immediately loaded up with Thompsons and bulletproof vests and took off on safari. Instead, the office was all but deserted, staffed only by Inspector Sam Cowley, basically the agent-in-charge (though the chain of command was muddy as most thought celebrity agent Melvin Purvis was calling the shots), Special Agent Herman “Ed” Hollis—another of the three Dillinger shooters—and a few others.

The obscure Cowley is the hero of this story, and it is a shame that his memory has diminished in the same way that the memories of the battle have perished. At 36, Sam was a “late-blooming star,” according to Bryan Burrough’s superb Public Enemies. He, not Purvis, had supervised the Dillinger operation. A Mormon who’d spent two years in Hawaii on missionary duty, he was father of six kids, worked to beat the devil down, and had a superb organizational and investigative mind. But he was no gunman. It’s quite possible he’d never fired the Thompson that was transported to the Division’s No. 13 car, a big blue Hudson, that day. The other gun taken was a Remington Model 11 riot gun, a semi-automatic that was a Browning Auto-5 built under license by Remington. We don’t know which agent anticipated using which gun, but it made far more sense that the experienced Hollis, a veteran of seven years on the street and a noted Thompson marksman, was planning to deploy the subgun, leaving the riot gun to Cowley as backup. Unfortunately, that’s not the way it worked out.

In Number 13, Hollis and Cowley headed out of the Loop, west to Northwest Highway and then north on an intercept route. But theirs would not be first contact with the gangsters.

William Ryan and Thomas McDade were two young agents who got the word fast, and were sent to Northwest Highway to precede Cowley and Hollis. They were first to intercept Les’s Model A five miles before Barrington as it entered the town of Fox River Grove. However, they were woefully under-armed, Ryan with two “Super .38s” (as they were called in those days) and McDade with a single .38 Spl. revolver. When, upon spotting the Ford, they U-turned and tried to make the felony stop, they got a magazine load of full auto in response. So aggressive was Les that, after a series of crazed U-turns, just like a Great War dogfight between SPADS and Fokkers, he actually ended up chasing them. Overwhelmed by the buckets of full metal jackets coming their way, the agents decided to disengage. McDade stepped on the accelerator so hard that they flew through Barrington and when they came to a bend in the road, flew off of it and ended up stuck in a field. There, they got out and took cover, expecting the imminent arrival of their heavily armed opponents.

All this would be a footnote to history but for the fact that one of Agent Ryan’s Super .38s penetrated the hood of the gangster car, puncturing the radiator and the wounded vehicle, with its cargo of unwounded but heavily armed gangsters, plus one very scared young woman, began to lose speed, leaking steam. That’s why what happened eventually took place, and that’s why it occurred where it did.

Cowley and Hollis saw the end of the Ryan-McDade engagement and took their own hasty U-turn across the median strip. It is at that point, I believe, that Cowley took up the Thompson because Hollis was behind the wheel. Thus, do glorious crusades turn to catastrophes.

Cowley engaged, but he cannot have done too well, shooting from one racing automobile at another racing automobile on a ribbon of bouncing highway at high speed while the gangsters evaded—they tended to be superb drivers and Les was no exception—and answered in kind. They had three full- or semi-automatic arms: a Thompson in .45 ACP, a Winchester 1907 semi-automatic chambered in .351 Winchester Self-Loading (WSL) and finally, and most terrifyingly, a Colt Monitor, in high-powered .30’-06 Sprg., capable of shredding cars, “bulletproof” vests, most barricades and everything else on earth short of vault steel. But Chase, who was firing the Monitor, never scored the engine hits that would have put the agents out of the game.

On the other hand, the gun cannot have been easy to handle. Though built by Colt and called a “machine rifle,” it was a tactically modified Browning Automatic Rifle, meant for police work, prison guards and industrial security. Colt had built 125 of them in 1931. And as good as it was for law enforcement, it was maybe even better for law breaking. According to an FBI interview with Baby Face associate Joseph “Fatso” Negri, Les had sent two minions to New York to buy “this new machine gun, this new type.” You can readily see why: it was ideal for bank work. The Colt engineers had shortened the stock and barrel, attached a stubby pistol grip behind the trigger guard, enlarged the fore-end, generally lightened it to 14 lbs. and attached a swollen, 12-slot Cutts Compensator to cut down on the muzzle rise that unleashing 20 .30-’06s in two seconds must inevitably generate. Often credited for shootings at which it was not in evidence (the deaths of Bonnie and Clyde, for example), its presence is one of the facts the FBI files confirm; they contain the statement by Negri about its acquisition, Chase’s explicit identification of it in an interview with Special Agent E.J. Connelly and the presence of nearly 100 rounds of .30-’06 ammunition in the Model A the gangsters would abandon (though one un-gun-savvy agent postulated that the .30-’06 might suggest they had used a Springfield!)

The gangster car lost power and slewed right, took a right down a dirt road and sloughed to a halt, amid an obliterating cloud of dust, dead on its tires, resting halfway in a shallow ditch. Hollis, in Division 13, passed them and pulled to the shoulder of Northwest Highway 152 ft. (by later Division measure) from the Model A. The two cars had come to rest at right angles to each other at the corner of a Barrington parkland, with nothing but grass and stunted trees between them. Both cars emptied, Helen Gillis took a powder (at Les’s urging, by her own account) and four men and three or four machine guns and a short-barreled, semi-automatic shotgun went to war. It may have been the only time in history that the head manhunter and his quarry faced each other over automatic weapons on the field of battle. It must have lit up the quiet suburb around it like the Fourth of July as they hammered at each other from a distance of 42 yds. Hollis learned early that his shotgun pellets couldn’t carry the distance; he fired a few rounds and then put the shotgun down, reserving it for later close-quarters work, not using the Colt .38 Super he carried. Cowley sprayed and prayed with the Thompson, again expending ammunition. As for the bad boys, Les was the most effective, going from gun to gun (his Thompson jammed, he traded off with Chase for the Monitor and finally went to the ’07.) With plenty of ammunition, he kept up a steady stream of suppressive fire, making certain, however, not to splatter the Division car which he knew they’d need. Chase fired, sometimes—this is a previously unreported fact—with his Super .38 automatic, but without effect and likely his true goal was keeping his head down and his hide intact.

Two minutes into the stalemate, Les—as would Michael Platt in a similar felony-stop gunfight in Dade County, Florida, 53 years later—realized he had to end the fight, as more and more police and heavily armed Division personnel would shortly be on-scene. His only recourse was to take the FBI car now, which meant taking the FBI agents now, which meant walking into the guns. Call it bravery, call it insanity, call it what you will, the crazy little rooster grabbed a long gun and began his November journey into legend.

But which gun did he take? People have wanted to know for years, and all witnesses, cowering in gas stations across the highway, were too far away to make a determination. The two leading chroniclers of this fight, Bryan Burrough (Public Enemies), and Steven Nickel and William J. Helmer (Baby Face Nelson: Portrait of a Public Enemy) disagree. It is unfortunate that the Division crime scene investigators didn’t map the action by way of location and pattern of ejected cases. Indeed, it seems they only picked up one of each specimen, not understanding that the dispersal would have revealed the best narrative of the incident. Perhaps—no crime scene tape in those days—citizens flooded the area, picking up souvenirs, perhaps it hadn’t yet been conceptualized, perhaps they were more concerned with the chase than the facts. What ballistic evidence they collected is unsatisfying. The multiple scraps of bullets recovered in autopsy were worthless: “No identification has been affected” states a Division lab report, of the fragments found in one agent, and the information is even more vague in that of the other.

Only the circumstantial remains. Monitor, Thompson or Model ’07? I’d discount the ’07 because it didn’t fire fast enough and had only 10-round magazines. That fact is supported via the low quantities of .351 ammunition he had on hand. The Thompson had jammed; he didn’t trust it either. On the other hand, Les had paid thousands for the Monitor, and it’s hard to believe that’s not the tool his gun-sharp imagination would have preferred. Sending out its rounds at more than 2,500 f.p.s., controllable because of the giant compensator, handy because of the pistol grip, scaled down for a short-statured fellow, designed originally by John M. Browning for “walking fire” against enemy trenches in the Great War, immensely powerful in comparison to the other two, legendary in gangster culture (of which Les was deeply cognizant), it was the psycho-berserker’s dream come true. I said he was crazy, not stupid. One forensic fact supports this conclusion, while none support any other. A “copper pellet found in the (Division) Hudson is believed to be only the casing of a bullet of .30 caliber,” the lab report states. How could a .30-’06 case end up in the government car if Les hadn’t carried it there on his mad walk to death and infamy? He fired, perhaps the fatal shots into Sam, and one of the powerfully ejected cases sailed through the open window of the nearby vehicle. It is possible, though unlikely, that the case caught in Les or John Paul’s cuff or lapel or pocket, and later slipped out. But what explanation do the percentages favor?

Only one witness to these events survived. Chase told agents on Dec. 28, 1934, “Jimmie Gillis [Les] at once got out of the car and grabbed the Browning machine gun I had. I also had a .38 Super automatic pistol and we both started to fire at the Federal agents. I fired at both of them. Jimmie Gillis ran up toward them with the machine gun ... .” He has to have meant the “Browning” machine gun.

It is not known if Sam hit him early or late, or if he hit him with just one .45 or six—another disagreement between Burrough and Nickel and Helmer. Regardless, all the Tommy rounds were in the belly and all were through-and-throughs. What is known is that Les closed the distance nevertheless, firing and reloading, perhaps cursing, perhaps snarling like Cagney or laughing like Gable or looking noble like Tracy, certainly without thought to self, Helen, Ron, Darlene or mom. He put two .30s into Sam (belly and chest), whose Thompson ran dry before the gangster was even halfway there, and poor Sam had neither a second drum nor the skill to reload. Nor did he have—no record exists, at any rate—a handgun with which to divert. Meanwhile, Hollis regained his shotgun, probably held for mid-body but forgot about buckshot trajectory, and put 10 pieces into Les’s legs of 10 shells dispatched. Must have stung like heck, but did little to end the fight. With the Thompson, marksman Hollis would have shot the gangster’s knees out from under him and dumped the rest of the drum into the fallen body. It was not to be. Les whirled, found that Hollis had retreated across the road, was out of shotgun ammunition and was drawing his Super .38, whereupon Les shot him three times, once in the head.

And then it was over. When the shooting stopped, Les got in the Hudson, losing blood fast, and drove to the Ford. There, he and Chase loaded their guns in the stolen government vehicle. Helen re-appeared on the scene and the three drove away.

A good question might be: what can we learn from the battle? One thing: don’t just have a gun, have the right gun. Hollis could have put Les down with the Thompson; with the Remington he was of very little use. Another lesson: practice, practice, practice—but practice right: He should have used his Super .38, firing prone, two handed, as that round’s velocity and straight-line trajectory could have gotten the job done, ending up center mass in Les. But he hadn’t been trained to two-handed prone shooting. In fact he hadn’t been trained to anything! The soon-to-be Bureau’s firearm training program didn’t begin until 1935!

As far as Sam is concerned, it seems probable that he too never logged any range time with the Thompson. The Division had only been authorized to carry firearms since the Crime Bill passed in June 1934. Of course, agents carried before then, as the heavily armed Little Bohemia raiders proved in April, but there seems to have been no bureaucratic pressure to get administrators such as Sam on the range. It might have saved his life. Practice, practice, practice. And second—this should be a universal rule for all law enforcement personnel and citizens who go in harm’s way—it proves that after “Have A Gun,” the second rule of gunfighting is, “Have Enough Ammunition.” Sam couldn’t imagine he’d need more than a 50-round drum! For his apostasy he was punished by a furious demon with the most terrifying infantry weapon on the planet.

There were no happy endings in Barrington that day: Les did receive a mercy none of the men he killed did: he died in his wife’s arms. He actually died—of blood loss—before Sam, who perished after surgery at 2 a.m. Hollis was comatose and died on the way to the hospital. Chase was arrested in December and spent the next 33 years in prison. Helen was arrested and charged with “harboring” a criminal. How just was this? I’m not sure. It seems like he harbored her, not the other way around, and that her real crime was being Mrs. Baby Face Nelson. She was incarcerated for a year.

The FBI’s records are full of fascinating facts about the event. For one thing: these guys weren’t just loaded for bear, they were loaded for bears, a lot of them. Found in the abandoned Model A: three bulletproof vests, five empty magazines for .38 Super automatics; two filled machine gun magazines (presumably Thompson 20 rounders); 200 rounds of loose .45 ammunition, three empty .351 magazines, three boxes of .30-’06 Sprg. soft-nose ammunition; one box of Springfield boattailed ammunition, five boxes, .45 Colt automatic ammunition, two boxes of Springfield bronze-pointed ammunition. One tan briefcase containing one loaded 100-round drum for the Thompson submachine gun; 10 boxes .22 Long Rifle; one Colt Ace .22 Long Rifle pistol and magazine. The last is a revelation: Chase had bought the M1911 variant with a lightweight .22 slide and barrel. Perhaps he and Les used it for low-cost practice on their various travels.

Two other facts are even more interesting, and may illuminate long-lost realities of mob culture. Both the Thompson and the .351 WSL Model 1907 had been used before—but not by Les. Division forensic case comparisons revealed that the Thompson had been present at the South Bend job on June 30, but it wasn’t the gun with which Les had sprayed downtown. Rather, it was the gun Charles “Pretty Boy” Floyd used in the bank to fire a burst into the ceiling to make the point that a robbery was now in progress, and a few minutes later, to suppress police fire on the getaway car as the boys climbed in for the escape. Had he and Les “traded” guns like teenaged girls swapping clothes? Hard to believe, as they detested each other.

Even more remarkable, the .351 cases from the ’07 that Les used revealed that it was the rifle also fired by Homer Van Meter at South Bend, where he’d fatally shot police officer Howard Wagner and used it (very coolly, reports indicate) to also drive back police during the final getaway, before he was knocked unconscious by a ricochet. He and Les are said to have really despised each other on dozens of issues, and so the fact that Les ended up with the rifle seems quite baffling.

The most reasonable explanation is that both guns were on loan from organized crime, which must have maintained an armory. Boys needing big heat for a raid could check out Tommys, presuming the mob didn’t need them for upcoming garage massacres, and then return them with a cut of the swag afterwards. Thus, both Pretty Boy and Homer returned their guns. A few months later, Les, increasingly paranoid after the deaths of his contemporaries, must have checked them out, unknowingly, to supplement the power of the Monitor. Perhaps he’d wanted two Thompsons but the armory only had one available—which is why he ended up with the Winchester ’07. Or perhaps he recognized Homer’s rifle, and appreciated the tactical attributes of the ’07, which was extremely similar to the as-yet-to-be-invented M1 carbine, which would prove so useful in years ahead. Like so much about the Battle of Barrington, we’ll never know.

The preceding is not meant as criticism of either Cowley or Hollis. They did what they could with what they had, and it should be recognized that in stopping Les, they saved the lives of all who would have fallen to his guns had they not. Given the ammunition in the car, that would have been many. The larger issue is a law enforcement bureaucracy, perhaps more aware of its national reputation than the welfare of its agents, that sends under-armed, under-trained, inexperienced men into battle with little chance to prevail. It shouldn’t have happened.

Two men with wives, children, bright prospects and even brighter hopes gave it all up to go against a bull-goose, loony-tunes, combat-mad, heavily armed gangster from hell—“He wouldn’t go down,” Sam said on his deathbed—for something called law and order, which is really just another way of saying “the rest of us.” They were outgunned, outshot and outfought.

They were not out-couraged.