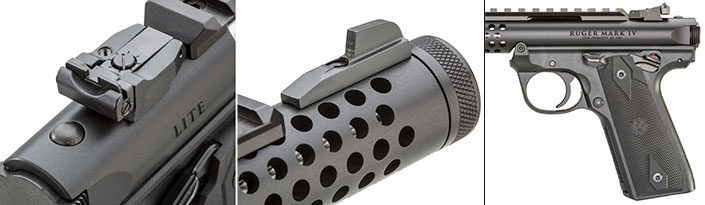

Ever been vexed trying to put a Ruger .22 pistol back together? A new takedown button on Mark IV models makes it a snap. Shown here is the Hunter (far. l.) in stainless steel and the polymer-frame 22/45 Lite.

When I was introduced to William B. Ruger, Sr., the great man asked me who I worked for, to which I replied, “Pete Dickey, sir.”

Dickey the brilliant, irascible, somewhat fearsome (at least at the time to me) industry veteran and longtime technical editor of American Rifleman, had known Bill Ruger since the 1950s.

At that point in his life (about 1992), Bill Ruger had limited mobility and severe arthritis, relying heavily on his longtime assistant and dear friend Margaret Sheldon. But his mind was as sharp as the day he walked into another American Rifleman technical editor’s office with a .22 pistol of his own design in 1949.

“Dickey, you say? He’s a son of a … ,” said Ruger.

“He said much the same about you, sir,” I answered without thinking. And I thought I had really stepped in it.

At which point, for just a few moments, the pain of his afflictions seemed to melt away as his bright blue eyes flashed with amusement. And, thus, I spent a few minutes in the presence of a man who had forever changed the landscape of American firearms. And he started with one gun.

The “.22 Ruger Pistol” was reviewed in these pages in October 1949 by Technical Editor Maj. Gen. Julian S. Hatcher, who wrote: “Shaped like a Luger pistol, the gun looks good and handles splendidly. It hangs and balances just right, and points naturally, which is a great aid in quick shooting. … We like this new gun a lot and at the very moderate price of $37.50 it represents real value.”

A simple blowback, the Ruger’s cylindrical bolt rode inside its tubular receiver, and it was cocked by retracting dual ears at the bolt’s rear. The extractor was on the bolt face’s right, while the fixed ejector was riveted to the frame. The magazine release was on the frame’s heel. Not user-removable, the barrel was screwed to the receiver. Recessed into the bolt’s top, the recoil spring and its guide rod were captive. The Ruger used coil springs instead of flat springs, and its blued steel frame was made from two metal stampings welded together and then cleaned up so as to hide the seam. It was an engineering marvel, and the guns worked very, very well. More importantly, the Ruger had style.

Now almost 70 years old, the gun has outlasted, perhaps even killed off, various High Standards, the beloved Colt Woodsman and countless others. Was the Ruger perfect? No, but it offered a combination of accuracy, ergonomics and price that couldn’t be beat. And while its operation has changed little through the years, it has evolved. There have been books written about Ruger .22s, the best of which are by Don Findley, but here’s a snapshot of the milestones.

The Ruger Standard Model .22 (later named the Mark I), was superseded by the Mark II in 1982, which remained the anchor for Ruger’s pistol line until 2005. The Mark II had a re-designed trigger pivot retainer, a new trigger, a sear-blocking safety that allowed the bolt to be manipulated in the “on” position, a new bolt hold-open device and scallops at the rear of the receiver for easier bolt manipulation. And the Mark II got a redesigned magazine, increasing capacity from nine to 10.

A polymer-frame model, the 22/45 was introduced in 1992 with molded-in stocks, and its grip angle replicated that of the M1911 (although, in my view, the Zytel-and-stainless gun was hideous to behold). On the bright side, the magazine catch was in the familiar M1911 position on the frame’s left, although Mark II and 22/45 magazines were not interchangeable.

In late 2004 (let’s just call it 2005), the Mark III replaced the Mark II, and brought with it some features shooters didn’t necessarily warm up to, including a line-spoiling, loaded-chamber indicator that projected out the receiver’s left side like a compound-fractured tibia. The Mark III also had a magazine disconnect safety and an integral key lock system. Ruger changed the hammer strut to incorporate a bolt lock on the receiver’s left. The shape of the bolt ears was streamlined, and the receiver was drilled and tapped for a scope base. There were two things shooters really liked—moving the magazine release to the frame’s left behind the trigger and re-contouring and opening up of the ejection port.

The 22/45 lasted until the 2004 introduction of the 22/45 Mark III, and although the new version included a loaded-chamber indicator and magazine-disconnect safety, its frame was much improved with a greater resemblance to the M1911 and stock panels that could be changed out. A 22/45 Mark III Hunter was made from 2004 to 2012, and the 22/45 Mark III Lite shaved a half-pound of weight in 2010 by using a 4 3⁄8" barrel tensioned inside an aluminum receiver.

Whew, we are finally to the new Mark IV, and its lineup includes the Target, Hunter, Competition and the 22/45 Lite. The tapered barrels of old are not cataloged—for now. I’m told many more models are coming, and soon. I requested two, the Mark IV Hunter and the 22/45 Lite as examples of both ends of the Mark IV spectrum.

The biggest news on the Mark IV is that it is easy, I mean incredibly easy, to take down—and put back together. Remember, on Ruger .22s the frame is simply the grip that contains the fire-control parts while the receiver (which bears the serial number) is the cylindrical top unit within which the bolt rides and to which the barrel is screwed. Make sure it is cocked and the safety is engaged, then just depress the new takedown button at the rear of the frame (at the apex of the beavertail) and the entire barrel and receiver pivots up, kind of like an AR when one pulls the rear takedown pin. This is because there is a new pivot screw at the top front of the frame that aligns with a corresponding semi-circular notch at the front of the receiver’s underside.

It’s in the reassembly that the service to humanity really kicks in on the Mark IV (see the sidebar below). Previously, one slid the receiver onto the frame, pushed it rearward, and then tried to re-insert the bolt-stop pin—and that was the rub. There is still a lug on the frame (screwed in place) that mates against the underside of the receiver at the front, but the takedown button has a rear-facing lug that engages a notch cut into the underside of the receiver’s rear. Simply line up the receiver on the frame screw, allow it to pivot down, then line up the bolt stop with its circular recess through the bolt and receiver, then press the receiver and frame together until it clicks. Easy, peasy.

Another Mark IV change is in how the frame is made. No longer are two steel halves welded together. A Mark IV frame is one piece of CNC-machined metal (except, of course, on the polymer-frame 22/45). I say metal because the stainless steel guns are of, well, stainless, while the blue Target models are of aluminum.

The Mark IV has blued-steel, bilateral safeties that are on the rear of the frame just behind and above the stock panels. Pivoting them down disengages the safety and reveals a red dot. Pressing them up blocks the sear, making a white dot visible. (On the Mark II, the safety was a button that slid up or down.) The bolt release is on the frame’s left and pressing it up keeps the bolt open. A holdover from the Mark III is the location of the magazine release on the frame behind the trigger. Gone is the internal lock, as is the loaded-chamber indicator, though the magazine-disconnect safety has been retained.

The distance from the center of the receiver frame screw (the pivot point) and the centerline of the bolt stop pin is the same for all the Ruger Mark IVs I have examined. And while I’m not sure Ruger recommends it, this means you can put the Hunter receiver on the 22/45 frame or vice versa. I tried it, and both guns functioned quite well. The magazine bodies for the Mark IV 22/45 and Hunter are the same, but they are not interchangeable due to the shape of their baseplates.

The gun on the cover, the 22/45 Lite Mark IV, has an aluminum receiver into which the 4.4" long tensioned barrel is screwed. Ruger has figured out the optimum torque to get the best accuracy out of its less expensive platform. There are lightening holes around the barrel (that also aid cooling) and the whole thing is topped with a 1/2x28 threaded muzzle protected by a blue knurled cap. On the .22/45 Lite, sights are a fully adjustable rear and a ramp front. The receiver’s top is drilled and tapped for the factory-installed Picatinny rail.

The Mark IV Hunter is a matte-finish stainless gun (save for the blue pins and controls) with an 0.88" diameter 6.88" long barrel. It weighs nearly twice that of the 22/45 (44 ozs.). The barrel has six longitudinal flutes (the one on the underside is shorter to make room for warnings), and the muzzle has a recessed target crown. Sights include a fully adjustable rear and a fiber-optic Hi-Viz front with white, green or red pipes. Stocks are rosewood-colored laminate checkered on the bottom half and bearing Ruger’s logo in red on a white metal escutcheon. It is a handsome, hand-filling gun that looks like it was made to shoot tight groups.

To test accuracy, both Mark IVs were fired at 25 yds. off a foam rest. The 22/45 was fitted with the Ruger Silent-SR, a .22-cal. suppressor made by Ruger in Newport, N.H., and a full “Dope Bag” will be conducted on the device for a future issue. Adding the Silent-SR was as easy as turning off the cap and screwing on the can. It was topped by a Leupold DeltaPoint on a Ruger Picatinny rail screwed to the top of the receiver at the factory. The Mark IV Hunter was fired with the DeltaPoint, too, although the Picatinny rail is not standard on the Hunter, (sold separately, item No. 90623, $25). As can be seen, accuracy was impressive, with the Hunter averaging 1.16" and the Lite turning in 2.15" for five consecutive, 10-shot groups at 25 yds. There were zero malfunctions of any sort throughout accuracy testing and function firing, during which slightly more than 500 rounds were fired through each pistol.

After Ruger knocked the competition on its collective derriere in the 1950s, makers have been challenging the Ruger .22 pistols ever since. There are some serious contenders out there, but the Mark IV is proof-positive that the champ will not go down without a fight. Technical Editor Hatcher wrote of the first Ruger, “One can readily see the designer of this gun knows something about shooting as well as designing,” and while this is a very different company than the one Bill Ruger and Alexander McCormick Sturm founded in 1949, I think we can apply Hatcher’s words to the team of guys designing guns for Ruger today.

Ruger Takes Steps To End World Profanity

I used to be the guy. To quote Liam Neeson in “Taken”: “I don’t have money, but what I do have are a very particular set of skills. Skills I have acquired over a very long career.” The actor might want my guns taken away even while he uses them to make millions at the box office, but it is a very good line. I used to be the guy that others could rely upon to reassemble a Ruger .22 pistol. Not long after I turned 21, I purchased a used pencil-barreled Ruger .22—after all, it is the greatest .22 pistol of all time. And I would take it apart and put back together, a lot. And it involved a lot of swearing.

I used to call it the “Keefe patented method.” It involved taking the gun, holding it upside down, shaking it and releasing a series of extremely colorful expletives. Once I saw that all the parts were aligned, I would jam it back together before the moon’s gravitational pull misaligned them. This was back in the pre-YouTube days, so I had to remember the trick. But when the parts all aligned, I could hear a choir of angels, and I knew that was my cue to shove the thing back together.

In 1991, I was hired as the most junior member of the NRA Technical Staff. I tested guns, I answered letters to the “Dope Bag,” I looked stuff up, I swept the range floor, I cleaned guns, I put guns in boxes and I sent them back. Every now and then I received guns I wasn’t supposed to receive. Guns we didn’t ask for. Typically it was a small, greasy box that, when shaken, rattled a lot, and inside would be a note that read:

“Sir:

“Can you put my Ruger back together!?

“Can you put my Ruger back together!?

“Thanks.”

It seems there was a percentage of NRA members who thought their $20 a year entitled them to the free service of me reassembling their Ruger .22 pistols. Invariably it would be accompanied by the member’s mailing label to prove that they were a member, which gave me his address. It is illegal for an FFL to just mail a guy’s gun back. The problem was I would have to find an FFL in a member’s area to send the gun back—after I put it back together. This was in the pre-Internet days, and not an easy task.

I remember one time a heavily taped box arrived—like a whole roll of strapping tape—and one of my bosses, Bob Hunnicutt, shook it, then handed it to me, saying, “Hey, Mark IV, this one’s for you.” In case you hadn’t noticed, I am Mark Alexander Keefe, IV, commonly referred to around the office, then and now, as “Mark IV.”

Humbled fellow NRA employees would turn up at my office door with a bag or a box. There are times that I wondered whether or not Ruger should just sell its .22 pistols in pieces in a paper bag, because that’s how they were going to end up anyway. I stopped re-assembling other people’s Ruger .22s as I moved on to being managing editor and was, therefore, no longer responsible for unsolicited paper bags or boxes with Ruger .22s in them. There’s even a guy named Dino Longuerra at Majestic Arms who has made a comfortable living off the fact that Ruger pistol owners have been so frustrated with reassembly that they send him their hard-earned money for his Speed Strip Kit.

It’s as if Ruger engineers didn’t even care how many expletives they were causing, day in, day out. It reflected a corporate callousness toward the proliferation of profanity, and a willful unwillingness for decades to deal with one of the largest problems facing mankind.

What did they know and when did they know it? Actually, they’ve known about it for some time. The gun that created Sturm, Ruger & Co., the beloved .22 pistol designed by Bill Ruger himself and reviewed by Maj. Gen. Julian S. Hatcher in American Rifleman in 1949, had a receiver made of two steel stampings welded together. They did such a nice job, you cannot even tell. It was incredibly innovative for its day. As a matter of fact, Ruger was awarded a very prestigious engineering award for this manufacturing feat decades ago. Apparently, in the pantheon of geeky engineering awards, this one is pretty high up there. It was enough to get the expletive-inducing-reassembly-process “Survivor”-like immunity for decades. Rumor has it, unsubstantiated, of course, engineers were forced to wear clown noses and kneel on bricks during new product meetings for even suggesting changing the frame manufacture method of the beloved Ruger .22.

The Ruger Mark IV happened because of an enterprising company engineer. It came about because he himself was so frustrated with reassembling his Ruger .22 pistols that he developed a fix on his own time at his shop at home. He brought it into the office one day. It really, really worked. No cursing, just press a button. Now it’s called the Ruger Mark IV.

After I disassembled and reassembled the prototype Mark IV a dozen or so times in mere seconds, with no shaking, holding the gun up to the light and no expletives, I told the assembled Ruger engineers I was very grateful that they had decided to name this improvement to humanity—this great step in the progress of human evolution—after me.

—Mark A. Keefe, IV, Editor In Chief