The Fieldcraft is a featherweight befitting a compact scope such as the 2-8X 32 mm Nikon Monarch 3.

Not so long ago we thought such weight almost unattainable. Today, 5-lb. bolt-action sporters aren’t all that unusual, but when you put the Barrett name in front of the new Fieldcraft line, heads are certain to turn. Perhaps some of us have been living in caves: Although they also produce “conventional” ARs, long-range rifles, and the 240LW lightweight machine gun, Barrett is probably most famous for its massive semi-automatic and bolt-action rifles chambered to .50 BMG and .416 Barrett.

The Fieldcraft is thus a departure, both good and interesting. I suppose any accurate bolt-action could be configured and employed in a wide variety of tactical roles, but the Fieldcraft (as the name implies) appears intended primarily as a hunting rifle.

Fit For The Field

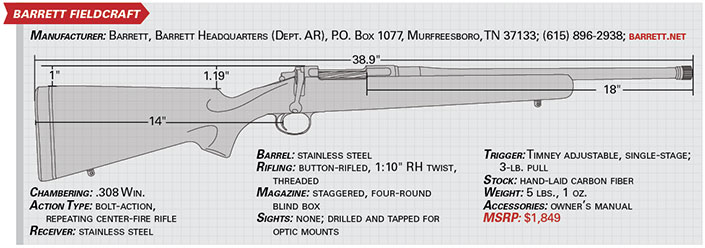

Clean and simple is a good way to describe the Fieldcraft. The stock is hand-laid carbon fiber with a right-hand cheekpiece, straight comb and a good recoil pad. Metalwork is matte-finish stainless steel. The Fieldcraft has a blind magazine (no floorplate), which is a good way to shave some weight. The magazine follower is polymer.

The action is a push-feed with a two-lug, rotating bolt, right-hand only, with the two-position safety located on the right just behind the bolt handle root. I would pretty much describe the action as a Remington Model 700 clone—except the bolt release is on the left side, opposite the cocking piece, and the hook extractor is wider, more akin to the old Sako extractor. Also, the bolt body is smaller in diameter, at 0.585", which also saves weight. This works because, while the Fieldcraft is initially available in both short and long actions, chambered for a total of 10 cartridges, all use the .30-’06 Sprg./.308 Win. rim diameter of 0.473"—no belted magnums or short magnums. Across the board, the capacity is four in the magazine plus one in the chamber.

The initial short-action offerings are .22-250 Rem., .243 Win., 6 mm Creedmoor, 6.5 mm Creedmoor, 7 mm-08 Rem. and .308 Win. In long-action, the Fieldcraft is offered in .25-’06 Rem., 6.5x55 mm Swedish, .270 Win., and .30-’06 Sprg. Barrels are standard 21" in short action and 24" in long action, and the short-action version is also offered in an 18"-long threaded version with a thread protector. Manufacturer’s specs are 5 lbs. for the short-action models and 5 lbs., 7 ozs. for the long action. No iron sights are provided, and the round-topped receiver is drilled and tapped for scope mounts, with two holes on the rear bridge and three on the forward ring.

My sample was chambered in .308 Win. with an 18" threaded barrel that I would describe as slender but not pencil-thin. My postal scale showed the weight at just a hair over 5 lbs., but let’s accept that, even on a simple rifle like this, weights are going to vary. Wood stocks vary tremendously, but even synthetic stocks vary a bit in weight. Chamberings also matter. If external barrel dimensions are the same, then the .30-cals. should be the lightest (bigger bore equals less steel) and the .22-250 Rem. will be the heaviest. Regardless, without a scope and mounts the .308 Fieldcraft is very close to 5 lbs. Although a joy to carry, make yourself a note: A 5-lb., .308 Win. (or a 5-lb., 7-oz., .30-’06 Sprg.) is going to bounce pretty hard—it is not a kid’s rifle.

The test rifle’s action was extremely smooth, feeding was flawless and the two-position safety was positive. The trigger is exceptionally wide with fine serrations, so it offers good purchase. It was set at the factory at 3 lbs. for a crisp, clean break. Let’s talk a bit more about the trigger. Barrett’s website identifies the trigger as a Timney (always good news). This trigger didn’t need it, but, of course, Timney triggers are adjustable. Other than identifying the trigger group, Fieldcraft’s operating manual makes almost no mention of the trigger, so I took the action out of the stock to make sure. Yep, the trigger is Timney, but this process (which I would have done anyway) led to a couple of interesting discoveries.

Assembly and Bedding

In order to remove the barreled action from the stock there are two action screws, one through the rear of the trigger guard into the tang and another forward of the blind magazine. A third, much smaller, screw secures the trigger guard—it is not necessary to remove it in order to pull the action from the stock. Interestingly, however, these three screws require three different hex-head drivers. That’s an insignificant detail, but I’m not sure I’ve ever seen that before. Out of the box, the action screws were extremely tight—a point to which I’ll return later.

The bedding surfaces are extremely smooth, with the stock reinforced with aluminum blocks at the action screw holes and the rear of the magazine well. The barrel carries a massive recoil lug just ahead of the receiver ring. When you take out the barreled action you can examine the action bedding, and you will see that this was done with care and precision. But the barrel channel tells a story, too. These days most manufacturers use free-floated bedding, certainly for the last two-thirds of the barrel channel. The reasons are obvious: Free-floating is easy, thus inexpensive, and often works. The Fieldcraft barrel is fully bedded in its channel. I already suspected this because, from the outside, there was no apparent gap. Curious, I applied the “dollar bill” test. Nope, you can’t get a piece of paper between the barrel and the channel.

The inside of the barrel channel is gorgeous, smooth as glass, and it appears to make full contact with the barrel throughout its length. So, when the literature describes a “hand-laid” synthetic stock they aren’t kidding. If you’re of the school that prefers your barrel be fully bedded, you’re going to love the Fieldcraft. Although subtle and nearly invisible, I rate this the most unusual and distinct feature of the entire rifle.

Heading to the Range

The test rifle was supplied with Talley’s two-piece mounts, with rings integral to the bases—strong, light and (a blessing for ham-handed me) easy to install. I put one of the new Riton 3-9X 40 mm riflescopes on the sample Fieldcraft and headed to the range in the late afternoon, full of hopes and expectations.

That first session was a total disaster. The rifle came into zero at 50 yds. easily, but when I switched to the 100-yd. frame to shoot groups things deteriorated quickly, with groups quickly expanding from clusters to shotgun patterns. At first I thought it was my fault; the little private range I use faces west up a canyon, perfect for mornings and okay at midday, but the light gets difficult in the late afternoon. But this wasn’t just the light; something was seriously wrong. Yep, sure was—not one but two (of eight) ring screws had sheared off. Yes, a 5-lb. .308 has recoil! Without question I contributed to this; screw pressure must have been uneven, which is my fault.

Fortunately, the screw heads popped off cleanly so the top half of the ring could be removed and the broken screws extracted without drilling, but I was done until I could find two more screws that would fit. This, by the way, was a frustrating exercise. I have 40 years’ accumulation of mounts and rings and hundreds of screws—but there’s little standardization, and I didn’t have a single screw that matched.

I was at their door when Bridge’s, our local gun shop opened, and Art Bridge and I combed through trays of screws. Yes, there’s one … and, finally, there’s another. Remount the scope, head back to the range, that time with good morning light.

This time there were no problems. The Fieldcraft came back into zero readily with the Riton’s adjustments precise and consistent. I only had odds and ends of .308 Win. ammunition on hand, and I needed two boxes each of three loads for this magazine’s protocol. Our August deer season was just around the corner on the Central Coast, and we’re a lead-free zone. Remaining stocks were limited, and mostly the homogenous-alloy bullets are what we have to use. I found two boxes each of 150-gr. Barnes VOR-TX TTSX and Winchester Power-Core, both copper-alloy bullets, and two boxes of Hornady’s 168-gr. ELD-Match, a lead-core bullet.

I started with the Hornady load because, after all, I expected the best results from a match bullet. It shot fairly well, but barrel heat quickly appeared to be an issue. Three-shot clusters were consistently tight, averaging about one minute-of-angle (m.o.a.)—but five-shot groups were far more challenging. Mid-morning temperatures already in the 90s weren’t helping.

As we know, the accuracy protocol for this publication is the average of five, five-shot groups. Starting from a cool barrel, I tried a couple at a normal, consistent pace; the first three shots stayed together, but the fourth and fifth shots started to wander, quickly doubling the group sizes. Okay, the rifle always has to tell you how it wants to shoot: Hot or cold? Clean or fouled? I slowed way down, taking my time between shots, cooling the barrel between groups, and cleaning the barrel every 10 shots.

Accuracy and Comment

As the accompanying table indicates, the average of five, five-shot groups with the ELD-Match load was 1.58". Surprisingly, the Barnes TTSX came in better at 1.40". A hunting bullet beat a match bullet—proof that there’s no telling what loads a given rifle will shoot best. This rifle didn’t care for the third load, the Winchester Power-Core, averaging a bit less than 2.5". In all three cases, however, I’m not certain these results tell the full story. Even at a very slow pace, in most cases the first three shots were tighter than the last two. In terms of a five-shot-group protocol, I don’t think it’s cheating to fire very slowly, and for sure it only makes sense to cool between groups. I think the accuracy average on this particular rifle would have been a whole lot better if I’d waited 20 minutes between shots, but that seems off the page, defeating the purpose of the protocol.

There were also some interesting anomalies. The very best of the 15 groups was 0.960" with Barnes TTSX—but wait, there’s more! A lot of the groups had uncalled “fliers” somewhere in the sequence. Often it was the fourth and/or fifth shot—attributable to barrel heat in hot summer weather—but not always. One group with Barnes TTSX had four shots measuring 0.385", which is spectacular, but it was the third shot that wandered, more than doubling the group. In any case, this particular barrel was sensitive to heat. It would be interesting to run the same protocol on a sub-freezing morning, but that would be long past my deadline.

Since I had to twiddle my thumbs and wait for the barrel to cool, it was actually between groups when I took the barreled action out of the stock. I said I’d come back to this, and it’s an interesting point: I like the fully bedded approach, but without using a torque wrench, it is extremely unlikely that you will take the rifle apart and put it back together with exactly the same screw tension.

A word to the wise: With a fully bedded barrel this can cause a significant shift in zero, and in this case it did. One of the things I noted about this rifle is, despite the ultimate group dispersion, the first shot was consistently spot-on. So, after reassembly, the first shot was high and left. Instead of guessing, I walked out to the target and measured it, easy with the 1/2" squares on the Hornady target. That strike was 3" left and 2" higher than I wanted. So I moved the Riton scope 10 clicks right and eight clicks down. By this time the barrel was cool again, and the next shot was exactly where I wanted it. This little incident speaks well of both rifle and scope.

Another small point worth noting, small because I don’t know if this is unique to this rifle or common to the Fieldcraft family: There are fast barrels and slow barrels. This barrel is really, really fast, which probably indicates close tolerances and smooth rifling. Factory specifications for the three loads, presumably with 24" barrels, are: Hornady 168-gr. ELD-Match, 2700 f.p.s.; Barnes 150-gr. TTSX, 2900 f.p.s.; Winchester 150-gr. Power-Core, 2820 f.p.s. Actual chronographed velocities from this 18" barrel were, respectively, 2645, 2827 and 2779 f.p.s. These are very small losses from such a short barrel.

No .308 Win. rifle has truly brutal recoil, but at 5 lbs. plus scope and light mounts, this Fieldcraft kicked pretty hard off the bench. That’s a necessary evil, but with “groups for score” fired, I spent some time shooting it offhand and from sticks. It felt good and handled well, and, after all, it is a hunting rifle—and it was a whole lot more pleasant to shoot from field positions! The .308 Win. is, of course, a fantastic workhorse cartridge and will probably prove to be the most popular option. But given its weight, the Fieldcraft will be a lot more fun to shoot in the other short-action chamberings.

In sum, the Fieldcraft is a great little rifle. It’s a whole lot different from anything else Barrett has offered, but it is unquestionably fit to carry the Barrett name, and it comes out of the box absolutely complete and ready to go to work. I suspect we’ll be hearing about some of the work it has done as the 2017 hunting season—the Fieldcraft’s first—progresses.